|

|

|

Cross-posted by RACE.ED

‘We are now in the age of Du Bois’, declared Aldon Morris in his widely acclaimed study, The Scholar Denied: W. E. B. Du Bois and the Birth of Modern Sociology. In this, Morris meticulously charts the intellectual contribution of Du Bois (1868-1963) to the social sciences broadly conceived, and sociology in particular, to argue that this remarkable figure could no longer been treated as peripheral, or an ‘add on’. After all, few sociologists pioneered as much as Du Bois, including in, amongst other areas, both quantitative and qualitative methodologies, especially social statistics and urban ethnography, reconciling questions of political economy with social movements (not least in charting the suppression of Atlantic slavery), as well as foregrounding relationships between the self and society, and doing so in ways that prefigure questions later posed in the politics of recognition. For these reasons I am not alone in arguing that Du Bois has bequeathed to sociology a cluster of normative categories that compel us to move beyond a kind of formalistic inquiry, and through which we might be more open to uncovering sometimes submerged features of social life (1).

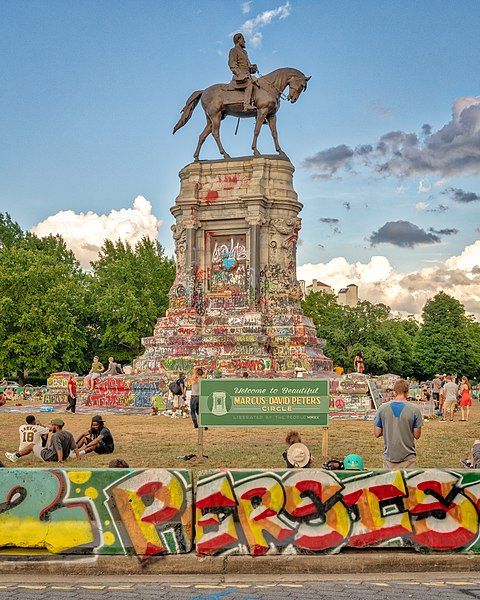

On 8th September 2021, a crowd gathered on Monument Avenue in Richmond, Virginia, USA, near the base of its iconic statue of Confederate General Robert E. Lee. The atmosphere in the crowd was jubilant as workers positioned a crane, wrapped the statue in a harness, and finally–after an hour of preparation, a year of court cases, and 131 years of racial terror set in stone–pulled the statue down from its plinth.

The equestrian statue of Robert E. Lee, Commander of the Confederate Army, is, and always has been, a symbol of white supremacy. Its removal creates the opportunity to change the meaning of the space it once occupied. For the past year at the Centre on the Dynamics of Ethnicity (University of Manchester), we have interviewed activists, policymakers, and cultural workers involved in contesting fourteen statues of slavers and colonisers in five countries. We have also explored the meanings of statues of empire and colonialism with young people from Manchester Museum’s OSCH Collective who shared how statues of white supremacy in towns and cities they call home impacted their sense of belonging. Our research highlights how anti-racist activists draw from global movements to contest local histories and memories. Equally, we consider how strategies for removing Confederate statues in the US (for example) might provide lessons for challenging imperial statues in the UK.

Discussions of contemporary white supremacy are seemingly everywhere: the election of Donald Trump and the January 6th insurrection, the murder of George Floyd, Brexit, the rise of the Alternative Right and white supremacist violence, and the coordinated efforts to deny racism and not educate children about the history and contemporary reality of race. These loud and important flashpoints, however, can unintentionally obscure the wider function and embodiment of white supremacy. That it is global and interconnected, is about systems and structures of power and not individuals, often hides in plain sight, and does not need ‘white’ bodies to sustain its power and replication.

For over a decade I have travelled to collect field data on race, globalization, development and labour in different Global South geographies. Through these engagements similar patterns became clear: countries in the Global South were beholden to policies dictated by the Global North. National groups racialized as white, or that exhibited a proximity to whiteness, were typically in positions of political and economic power. Those racialized as Black, or represented a distance from whiteness, had the worst material conditions. These seemingly very apparent global racial inequalities were often understood, though, as not about racism but about economic development, skills, capabilities, culture – essentially, anything but race.

The murder of George Floyd in the spring of 2020 sparked an outcry against police brutality and racial injustice in the United States. In the wake of the killing, support for the Black Lives Matter movement rose sharply among white Americans. Shows of support ranged from the (controversial) posting of blacked-out photos on Facebook and Instagram, to patronage of black-owned businesses, to marching in BLM protests.

We are now more than a year out from George Floyd’s killing. Much of the antiracist fervour expressed by progressive white Americans in 2020 appears to have fizzled. According to a Politico/Morning Consult poll, the percentage of white Americans with positive evaluations of the Black Lives Matter movement has declined significantly since last summer. Some see this change as an indication of the superficiality of many white Americans’ involvement in antiracism. While this may be true, our Identities article, 'Racemaking in New Orleans: racial boundary construction among ideologically diverse college students', points to the important role of racial boundary construction in limiting white Americans’ involvement in antiracist efforts.

In majority white countries, the Black Lives Matter protests that unfolded after the murder of George Floyd were accompanied by the intensification of public debates on systemic racism and white allyship. Some media focused on Black-white couples, discussing the impact of these events on white partners’ understanding of anti-black racism in their Black partners’ lives. As part of the ERC-funded project ‘Regulating Mixed Intimacies in Europe (EUROMIX), over the past four years I have explored Black-white couples’ experiences of racism and discrimination in their everyday lives.

Drawing from ethnographic fieldwork I conducted in 2018-2019, my Identities article, ‘Interracial couples and the phenomenology of race, place and space in contemporary England’, looks at partners’ perceptions of dis/comfort and un/safety across different contexts: when they jointly move in public spaces, choose where to make home, and travel for leisure. By juxtaposing these scenes, the article foregrounds a multi-layered economy of constraint and choice underpinning the lives of the opposite and same-sex couples that I have met and/or interviewed.

Arab Americans have been categorised as White on official government forms for several decades, which grossly misrepresents this population. Advocacy groups unsuccessfully fought during both the Obama and Trump administrations to have the ethnicity category expanded in the 2020 Census. The ramifications of this community remaining uncounted include lack of funding for social, education, and health care services and less leverage in political issues. Along with negating the incredible diversity within this group, such categorisation excludes Arab Americans from affirmative action programmes.

The recognition of this ethnic group on government forms would allow for their inclusion in such programmes, which is crucial given the prominence of discrimination in the US. However, the irony lies in how mainstream society tends to change their view depending on current events. When there are no crises involving Arabs around the world, Arab Americans are seen as White. However, when a crisis does occur involving Arabs – as either transgressors or victims (i.e. 9/11, invasion of Iraq) – they will be gazed upon as ‘Other’ and enemies of America. The rise in hate crimes against Arab Americans – and anyone who fit into the public’s notions of what an Arab or Muslim looks like – following the terrorist attacks of 9/11 is a prime example of this phenomenon. Consequently, regardless of being labeled as White, Arab Americans have experienced discrimination similar to other racially visible minority groups. This begs the question: if they are recognised as White, then why are they treated as ‘Other’?

In an age defined by hyper-visibility made possible by always-on digital media, brought to our fingertips by the smartphone, we are regularly fed images of (often extreme) racial violence. The circulation of the long eight minutes and forty-six seconds of George Floyd’s murder by Minneapolis police officer, Derek Chauvin, in May last year reinvigorated a movement across the Global North, against the disposability of Black lives. However, there is no simple way to untangle the dilemma that there is a seeming need to witness the death of a Black person to trigger a response. As LeRon Barton wrote, ‘watching Black men being beaten on video is the new lynching postcard.’

Despite the energy unleashed by the Black Lives Matter protests of 2020, it is not surprising that many antiracists remain sceptical about the lasting commitment of those momentarily inspired by the uprising. Will 2020’s #BLM moment be superseded by a return to scrolling through images of racial violence to which we seem increasingly immune? These questions animate my Identities article, ‘Looking as white: anti-racism apps, appearance and racialized embodiment’, which looks at mobile apps for reporting on and educating about racism. As mobile technology is such a part of our everyday experience, it can clearly be a powerful tool for pedagogy. This is the aim of one of these apps, the Australian-based Everyday Racism app. The app encourages ‘bystanders’ to learn about the experiences of people of colour and Aboriginal people who face racism in their daily lives. It uses gamification to deliver text and video messages to app users about these experiences in the aim of building empathy and encouraging what Australian racism researchers call ‘bystander antiracism’ (a strange appropriation of a concept used to describe those who stood by and did nothing during the Nazi deportation of the Jews).

Media coverage of recent police killings of Black citizens, including George Floyd and Breonna Taylor, and the related Black Lives Matter protests, have reignited a long-smouldering national conversation about race in America. These acts of police violence are part of a centuries-long pattern of institutional and systemic state violence against brown, Black and Indigenous people in America.

The killings and protests have prompted responses at both organisational and individual levels. Indeed, national organisations that contribute to the (re)production of bucolic white racial identities are facing a reckoning because of a growing awareness of the ways they contribute to making this violence possible and invisible to many white Americans. For example, this year the Boy Scouts of America formally supported Black Lives Matter, instituted a new diversity and inclusion merit badge, and acknowledged, ‘We have not been as brave as we should have been because, as Scouts, we must always stand for what is right and take action...’[1] Individually, many white Americans, who may have never thought critically about their racialised identity or privilege, are working to better understand their own identities and the institutions that make up their social landscapes. Yet even as racist state violence and resistance to it are made visually manifest in the media, many white Americans are still responding with surprise, shock and outrage because they live racially privileged lives free from such state terrorism, and are able to ignore the many manifestations of ongoing systemic racism.

In this current moment where so many white individuals are contending with the implications of their racial privilege in the wake of the #BlackLivesMatter movement, it is important to understand the nuances of white identities. Much of the activism and effort over this past year has focused on urging white individuals to develop an awareness of the scope of racial inequality and white privilege. Less attention has been given to how white individuals might ethically deploy this racial understanding, especially regarding how white individuals might negotiate their participation within communities in which they are deemed racial outsiders.

My Identities article, ‘Ivory in an ebony tower: how white students at HBCUs negotiate their whiteness’, examines one such group of white individuals navigating their whiteness in a space where they are deemed racial outsiders: historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs).

If we are to assume the Shakespearean platitude that 'the eyes are the windows of the soul', then it is not beyond our comprehension that visual images used by NGOs (non-governmental organisations) in their advertisements are carefully curated ideas over who or what is ‘seen’, and more importantly ‘how’ it is seen, and for whom. In today’s progressively changing and competitive media and communications environment, humanitarianism is now a profitable enterprise in our visual-as-currency economy.

On our television screens, in our social media applications and unsolicited pop-up email advertisements, and even among the rumpled pile of outdated magazines in the doctor’s waiting room, the public faces of the international aid and relief industry are seldom out of sight. Whether it is malnourished pot-bellied toddlers wearing western football memorabilia of seasons past, a despondent refugee mother in a displacement camp, or a vast horde of shaven-headed, undifferentiated Black and Brown masses in conflict zones, these images are the aesthetic currencies of commercialised suffering employed by humanitarian organisations to brand themselves and their strategic ambitions, and imbue western audiences with a philanthropic disposition. Visual representations are central to – and orbit around – the phenomenon and work of humanitarianism. When we think of humanitarian work, we often visualise much of the non-western, Black and Brown world. As image producers and disseminators, these organisations set the visual tone within which certain people and places are defined and comprehended – indeed, who (and what) they ‘are’, ‘aren’t’ and ‘ought to be’. 25 years after apartheid: are British-born South Africans signing up to the ‘rainbow nation’?2/10/2019

2019 marks 25 years since Nelson Mandela was elected as the first black president of South Africa. Finally, apartheid, the system of racial segregation institutionalised by the Afrikaans-led Nationalist Party in 1948, was a chapter closed. Since that time, South Africans of all backgrounds have been debating the extent to which the post-apartheid vision of ‘a rainbow nation’ -- a multicultural unity of people of many different nations -- is being realised.

This question is not only of interest and importance within South Africa. Against a context of rising populism and white nationalism across the Global North, are white people in South Africa really rejecting the privileges of white supremacism which they have enjoyed for so long? My Identities article, 'Reimagining racism: understanding the whiteness and nationhood strategies of British-born South Africans', examines this question by looking at one group of South African Whites: those who were born in Britain and migrated to South Africa. Many did so in the 1960s, 70s and 80s, through a ‘Ten Pound Pom’ scheme which offered them cheap passage, good jobs and comfortable accommodation on arrival. Whereas, at home in Britain, there was rising rejection of the apartheid system in South Africa, this group chose to up sticks and move to a deeply segregated society. How do they explain this, to others and themselves? And how do they now talk about the situation in South Africa today?

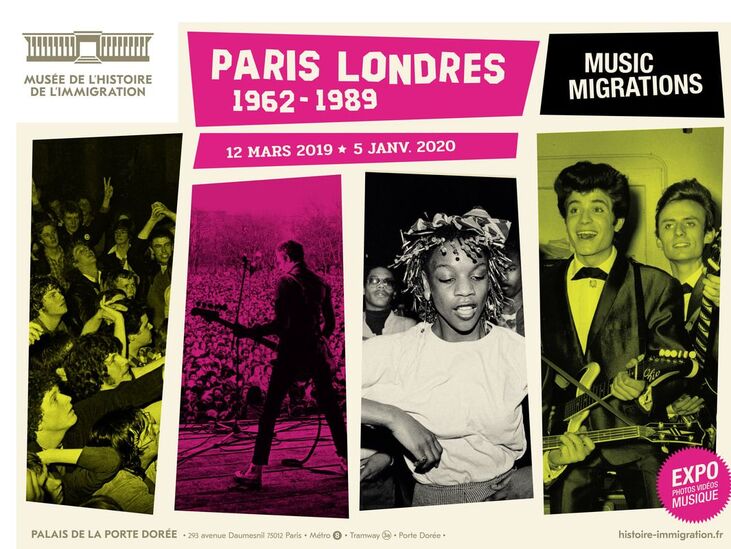

In 2019, Musée d’Orsay held an exhibition on Black Models, and the National Museum of the History of Immigration held a year-long exhibition on the musical contribution of migration to Paris and London. Why do we need a specific show to give black models an identity and an exhibition to demonstrate the contribution of post-colonial migrants to popular music?

In my Identities article, 'The whiteness of cultural boundaries in France', I explore the underpinnings of France’s relationship to the culture of the Other, through the scope of whiteness. I contend that whiteness can be defined as a kind of capital embedded in the routine structures of economic and political life and is therefore a relevant concept to analyse French cultural policy.

On April 15, 2013, two pressure-cooker bombs exploded at the finishing line of the Boston Marathon, killing five and injuring 264. In the absence of information about who the bombers were, Salon.com published liberal commentator David Sirota’s piece 'Let’s Hope the Boston Marathon Bomber is a White American'. Sirota argued that if the bombers turned out to be white, Muslims would be protected from an inevitable anti-Muslim backlash. A few days later, the bombers’ identities were revealed as brothers Tamerlan and Dzhokhar Tsarnaev, children of Chechen refugees who came to the United States when they were 16 and 8 years old, respectively. Interestingly, the brothers were phenotypically white and, as conservative commentators online were fond of saying, quite literally Caucasian (i.e. from the Caucuses). They were also, however, Muslims.

Sirota’s article provoked a firestorm across conservative media, and Sirota was accused of being race obsessed and blind to the threat of Jihadist terrorism. In our Identities article, '‘Let’s hope the Boston Marathon Bomber is a White American’: racialising Muslims and the politics of white identity', we analysed conservative responses to Sirota’s article, as well as the ensuing debate about whether the Tsarnaevs were, in fact, the white Americans Sirota had hoped for.  Photo credit: Jason Tester Guerrilla Futures. CC BY-ND 2.0. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nd/2.0/. Photo credit: Jason Tester Guerrilla Futures. CC BY-ND 2.0. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nd/2.0/.

The narratives presented in British public debates around terrorism have been long rooted in notions of increased presence of Islam in the public square as intuitively resulting in greater risk to the public. The most significant question this raises is who the ‘public’ refers to when discussing issues around securitisation. The recent horror of Christchurch represents something of an inverted scenario with the positioning, and following it we saw a series of Islamophobic attacks on mosques in Birmingham.

The connection between global and local events is significant because it explicitly requires us to engage in a process which, we argue in our Identities article, 'Securing whiteness?: Critical Race Theory (CRT) and the securitization of Muslims in education', is often absent. Our purpose in the article was to explore some of the ways in which Muslim communities are racialised and instrumentalised, rather than protected. Getting to grips with how Muslims have been located as stakeholders in national security in Britain is revealing. A large part of the Prevent counter-terror strategy relies on partnerships with Muslim communities. So in many senses British Muslims are the key stakeholder group in the securitisation process -- so how does it play out for them? How are their interests reflected in exchange for engaging in these partnerships with the state?

When you see images of French daily life or French people in magazines, films, or other media, what do you see?

Usually, it’s white people, with perhaps a few visibly non-white people depicted. But this is odd for multiple reasons. One, France has a long history of immigration, primarily from its overseas territories and former colonies. Due to years of colonialism, colonial slavery, and subsequent migration, ethnic minorities, or 'visible minorities' in French academic parlance, have long been part of French society. Secondly, France does not acknowledge or measure race as a separate identity category. So while France is a multicultural society, it does not, as a facet of law, distinguish between these different cultures. One is either French or not. This is France’s Republican model.

In October 2016, as the US election loomed, Farage (2016) wrote in an opinion piece in The Telegraph, a symbol of his media prominence:

The similarities between the different sides in this election are very like our own recent battle. As the rich get richer and big companies dominate the global economy, voters all across the West are being left behind. The blue-collar workers in the valleys of South Wales angry with Chinese steel dumping voted Brexit in their droves. In the American rust belt, traditional manufacturing industries have declined, and it is to these people that Trump speaks very effectively…. This kind of statement was not limited to far-right politicians claiming political support from the working class, but has become common in much of the political commentary since. To make sense of these developments, our Identities article, 'Whiteness, populism and the racialisation of the working class in the United Kingdom and the United States', examines the populist racialisation of the working class as white and ‘left behind’, and representative of the ‘people’ or ‘demos’, in the campaigns and commentaries.

If national security is in danger, the state can declare a state of emergency. This step will suspend normal legal procedures that allow the authorities to regain order and control.

What if politicians allege that the culture and identity of migrants and refugees are threatening the cultural cohesion and economic welfare of the nation-state? What if political leaders declare a national security emergency in order to get political support and funding for a wall? In my Identities article, 'Denmark’s blond vision and the fractal logics of a nation in danger', I show a new way to understand neo-nationalism, which is the kind that occurs within established nation-states, through the notion of a ‘nation in danger’, in relation to racialisation. The notion of the nation in danger is a specific logic that motivates a large ‘white’ majority of Danes in their perception and treatment of migrants, refugees, asylum-seekers and Danes of colour. It also separates for them who belongs to Denmark and who does not on the basis of racial, cultural and ethnic features |

|

Explore Identities at tandfonline.com/GIDE |

|

The views and opinions expressed on The Identities Blog are solely those of the original blog post authors, and not of the journal, Taylor & Francis Group or the University of Glasgow.