|

|

|

The COVID-19 pandemic profoundly transformed people’s lives, identities and practices throughout the world. It had particular effects on the group of international students who usually move frequently between home country and study destination. When the pandemic hit their study destinations in 2020, they had to take immediate action and plan migratory trajectories accordingly.

Chinese international students (CIS) also experienced a nationwide pandemic control policy at home that caused continuous travel constraints on international flights and passengers landing in China. The domestic policy had a profound impact on their migration aspirations – to remain in the study destination or to return home. Simultaneously, students reconfigured their perceptions of homeland. Our research, as detailed in our Identities article, ‘Migration aspirations and polymorphic identifications of the homeland: (Im)mobility trajectories amongst Chinese international students amidst COVID-19’, includes semi-structured interviews with 33 CIS studying in 23 cities of 10 European countries (including the United Kingdom). We aim to understand how students’ identifications of homeland – a cognitive assemblage of emotions, commitments and reflections towards their home country – intersect with their migration aspirations.

0 Comments

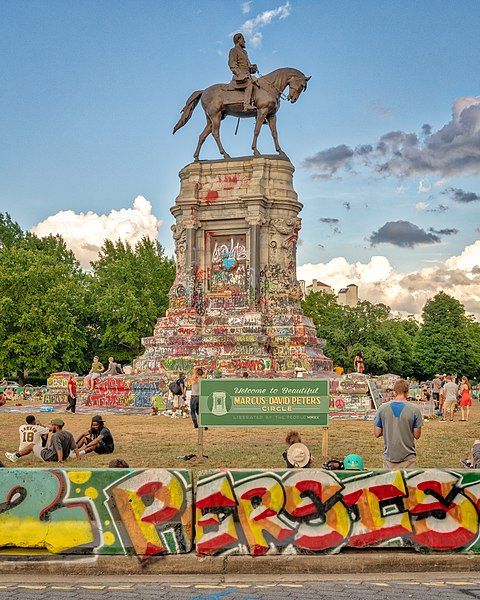

On 8th September 2021, a crowd gathered on Monument Avenue in Richmond, Virginia, USA, near the base of its iconic statue of Confederate General Robert E. Lee. The atmosphere in the crowd was jubilant as workers positioned a crane, wrapped the statue in a harness, and finally–after an hour of preparation, a year of court cases, and 131 years of racial terror set in stone–pulled the statue down from its plinth.

The equestrian statue of Robert E. Lee, Commander of the Confederate Army, is, and always has been, a symbol of white supremacy. Its removal creates the opportunity to change the meaning of the space it once occupied. For the past year at the Centre on the Dynamics of Ethnicity (University of Manchester), we have interviewed activists, policymakers, and cultural workers involved in contesting fourteen statues of slavers and colonisers in five countries. We have also explored the meanings of statues of empire and colonialism with young people from Manchester Museum’s OSCH Collective who shared how statues of white supremacy in towns and cities they call home impacted their sense of belonging. Our research highlights how anti-racist activists draw from global movements to contest local histories and memories. Equally, we consider how strategies for removing Confederate statues in the US (for example) might provide lessons for challenging imperial statues in the UK.

Romania has several multicultural regions, including the Banat in the southwest. During its time as part of the Habsburg and Austro-Hungarian Empires (1718-1918), cultural influences and economic developments from the West (German, Austrian, and Hungarian) made it an attractive destination for migrants. This continued after the Trianon Treaty and Romanian unification in 1918, as Banat was economically advanced compared to other regions to the East and South. Rapid industrialization and urbanization under the communist regime (1947-1989) and the subsequent removal of restrictions on movement in the early post-communist period also saw steady internal migration patterns.

Despite this long history as a recipient of migrants and cultures, the sense of nativism and place belonging is strong among Banateni. Proximity to Central Europe also led to a sense of discrimination, as Both noted, a Banat resident ‘would better prefer a German, Serbian or Hungarian than a migrant non-Banat Romanian’ in their village. In our recent Identities article, ‘Internal migration and stigmatization in the rural Banat region of Romania’, we attempted to uncover attitudes towards internal migrants and how these were understood by migrants themselves in rural Banat.

When we speak of borders, we usually either refer to the lines considered to separate nation states or to the actions we are asked to perform when arriving in another country (such as showing one’s identity document or choosing a green or red lane depending on the goods we wish to declare). However, researchers working in the field of border studies have long started to think about borders in a much larger sense as spatial phenomena related to processes of inclusion and exclusion. Today’s global cities provide numerous examples of such phenomena. From gated communities to gendered spaces or neighbourhoods described as ‘ghettos’, cities often display spatial orders that limit the free movement of their inhabitants.

I was inspired to study French banlieues through the prism of critical border studies after a series of encounters with colleagues from the Alsatian city of Strasbourg. Like many of their fellow Strasbourgeois, these colleagues often went to the neighbouring German town of Kehl, where goods such as fuel, cigarettes or basic necessities from discount stores are considered cheaper. In normal times, this border is not policed and thousands of commuters, tourists and shoppers cross the Rhine every day. In contrast, none of my colleagues had ever gone to the Neuhof, a banlieue with a poor reputation in the southern suburbs of Strasbourg. At university, I met a Comorian-born student who lived in this area. He told me that the most difficult part of living in this socially vulnerable neighbourhood were not the living conditions as such, but the police controls and the regular frisking he experienced at least every week when taking the tram to the city center. For him, the true border did not run along the Rhine; it separated his neighbourhood from the rest of Strasbourg. |

|

Explore Identities at tandfonline.com/GIDE |

|

The views and opinions expressed on The Identities Blog are solely those of the original blog post authors, and not of the journal, Taylor & Francis Group or the University of Glasgow.