|

|

|

Blog post by Ece Yoltay, Ahi Evran University, Turkey

My Identities article, ‘Queering trialectics among space, power, and the subject: spatial representations and practices of othered identities in Turkey’, is grounded in a critical analysis of the Foucaldian conceptualization of the relation between power and the subject. It does so by examining the construction of the concept of ‘supra-identity’ with the Repressive and Ideological State Apparatus in Turkey. Since the Republic of Turkey was established as a nation-state in a predominantly Muslim society, various legal and social regulations determining state-citizen relationships have been shaped in its political history (single-party period 1923-1946, multi-party period 1946-2018, Presidential system 2018-present). While each government in this history produces its own political interpretation of the 'ideal' citizen, the emphasis on Turkish and Muslim identities, particularly within the heteronormative social structure associated with Islam, has been common value for defining ‘supra-identity’. In Turkey's multicultural society, homogenizing differences over these identity values of the 'majority' has been deemed necessary for the 'unity of the state'.

0 Comments

Today, the world’s knowledge of Sweden is limited, and its image is often too unclear and out of date. So we need to unite around a clearer, unified image that better reflects contemporary Sweden – an image that is also distinct and relevant to the people we want to reach.

- Swedish Institute, 2009

Like handbags and toothpaste, countries are being branded. National identities and cultures are used to brand countries. For example, Malaysia is branded as ‘Malaysia, Truly Asia’, pointing to its multiculturalism. But identities are never static, and communities are diverse. So, which identities and whose cultures in the country are promoted, and which excluded?

The Swedish authorities are branding their country too, but they want the brand to be honest and inclusive, not fabricated and selective. Did they succeed? In our Identities article, ‘Representing Sweden: packaging Swedish identity through curators of Sweden’, we examine a recently concluded nation branding project, Curators of Sweden (CoS). The project used Twitter as a platform and each week a ‘Swedish’ person was chosen as a curator to tweet whatever they liked through the @Sweden account. The curators were chosen because they represented ‘values, skills, and ideas’ which, according to the campaign, ‘all combined, makes up Sweden’. CoS started on 10th December 2011, the Nobel Prize day, and ended in September 2018. A total of 356 curators tweeted more than 200,000 tweets.

Today, national symbols serve as modern totems to distinguish and portray nation-states. Most of us watched the Tokyo Olympic Games and saw the pride and intense emotions that athletes and fans displayed in paying homage to their national flags and anthems at medal ceremonies. National symbols are usually chosen to reflect a single united nation, but they are often contested in divided societies, as they play a powerful role in preserving the collective memories and reflecting the cultural narratives of groups.

It is therefore difficult to establish symbols which reverberate with the cultural legacies of diverse groups in divided societies, and in particular, post-conflict societies. Although some groups might identify less with official national symbols in diverse societies, nationalism scholars believe that attitudes can change over time. Due to the pervasive display of official symbols, people can become accustomed to them, and memories of former symbols associated with particular cultures can fade.

The use of identity markers in sport has received considerable attention from scholars in a number of disciplines over a number of decades. This has been looked at in a variety of different sports and includes insightful studies published in Identities such as the works of Paul Campbell and Daniel Burdsey on football and Constancio Arnaldo on boxing.

In our Identities article, ‘Pretty fly for a white guy: The politics of race, nation and difference in professional boxing’, we look at the ways in which race and nation are (re)presented within the coverage of one particular fight. Boxing is a sport that relies heavily on binary divisions. In his book Boxing and Society, the sociologist John Sugden noted how success in the ring could ‘symbolise not only individual achievement, but also racial and national superiority’. For the promotion of many championship bouts the hype around the fight is constructed around binary oppositions. This paper looks at the bout between Joe Calzaghe (a white boxer from Wales) and Bernard Hopkins (a black boxer from the USA) as a case study to explore the representation of identities. In attempting to tease out some of the key themes to emerge in the intersection of race and nation, we tried to understand how identities are portrayed within boxing. This work also highlighted further differences around the understanding of social class and core/periphery relations within a particular sport.

Patriotism is having a moment. From French President Emmanuel Macron’s claim that patriotism is ‘the exact opposite of nationalism’ to UK Labour Party leader Keir Starmer’s call for party members to be ‘proud of being patriotic’, centrist and progressive politicians are appealing to patriotism as a bulwark against the rise of right-wing nationalism. In the US, a July 2021 YouGov poll found that sixty-nine percent of respondents believed that a person could be considered patriotic while participating in a protest for racial equality.

These examples stand in contrast to other recent appeals to patriotism: an ultranationalist French political party established in 2017 took the name ‘Les Patriotes’. The Tory government has spent £163,000 on Union flags in the past two years, and has lent its support to the ‘patriotic’ One Britain One Nation campaign. And the same July 2021 YouGov poll in the US found that sixty percent of Republicans considered themselves ‘very patriotic’ – compared to only twenty-four percent of Democrats. Why is patriotism so appealing across the political spectrum? And what does this mean for the prospects of ‘progressive’ patriotism? My Identities article, ‘‘The opposite of nationalism’?: rethinking patriotism in US political discourse’, considers the multiple and contradictory – but always exclusionary – ways that patriotism has been used by politicians across the US political spectrum. Politicians of all stripes, I find, describe themselves and their supporters as patriots. Although few define the term explicitly, all frame patriotism as an implicitly positive love for one’s country. I argue that this vagueness allows politicians to position their policy agendas, and their own character, as ‘authentically’ American. Crucially, it also permits them to position their opponents as unpatriotic and, by extension, un-American. This sharpens any attacks on a politician’s opponent; even more dangerously, it hardens the borders between those who belong to the nation and those who do not. For non-citizens, migrants and racially minoritised people, appeals to patriotism bring exclusion and violence.

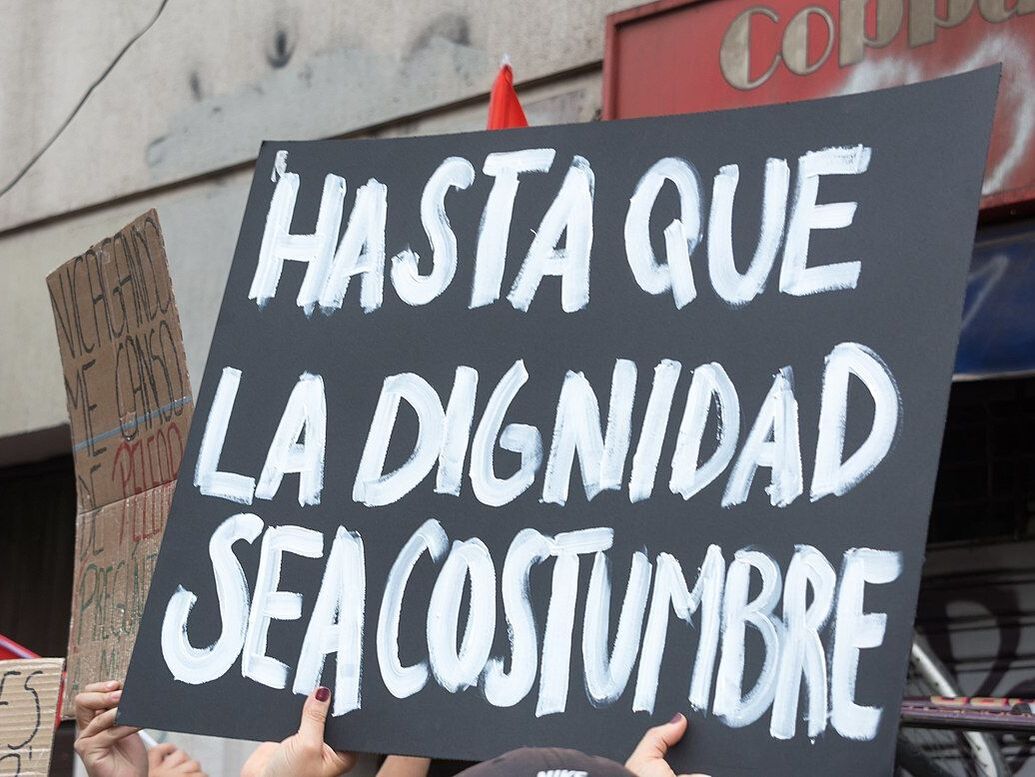

While writing our Identities article, ‘Disjunctive belongings and the utopia of intimacy: violence, love and friendship among poor urban youth in neoliberal Chile’, we had already started to witness a series of protests that recently culminated in the so-called Chilean ‘social outburst’ in October 2019 and the current process building a constituent assembly. Issues of quality of education, environmental concerns, shortcomings in the social security system, as well as long-standing efforts for the cultural and political recognition of indigenous groups gained increasing support over time. Yet, the many protests still appeared geographically scattered, and while people in the urban margins indeed felt uneasy with their life prospects, it was still uncommon to hear people articulate a more thorough critique of the neoliberal model that has prevailed in Chile for the past forty years.

In Los Acantos, the residents we met in 2012–2013 were conscious of these issues. Many of the young residents we met saw no way out in a world bounded off by invisible borders of social (in)difference and stigma. People were, in other words, aware of their almost impossible odds of socio-economic mobility and underneath the surface of monotonous low-income houses, the attentive ethnographer could feel the discontent. |

|

Explore Identities at tandfonline.com/GIDE |

|

The views and opinions expressed on The Identities Blog are solely those of the original blog post authors, and not of the journal, Taylor & Francis Group or the University of Glasgow.