|

|

|

In memory of co-author Monique Nuijten. Thank you for all your inspiration and the nice partnership working on this article together.

‘A Breaker is peaceful and calm. At the moment of dancing he expresses all his feelings, he expresses his anger, his love, his sadness, everything. While dancing he develops. Breaking turns them into better people.’ ‘The moment you start to dance and become a b-boy or b-girl everything in you changes, it’s like an armor you put on and you will never take off.’ ‘This is what I love the most, it is what makes me, it is why I keep on fighting, the reason why I am still standing, it is the reason why I can keep on following my dream.’ ‘It is my life, without it [dance] I can’t live, it is like the air.’ In our Identities article, ‘When breaking you make your soul dance’ Utopian aspirations and subjective transformation in breakdance’, we dive into the world of breaking by following the Naturalz crew in Ecuador. The quotes above from various crew members illustrate the importance and meaning of breakdance for them. Breaking is commonly analysed as a subculture of resistance. We analyse two – often neglected – dimensions of this resistance: the significance of utopian aspirations and the role of the body in subjective transformation. The breakers shape a new lifestyle for themselves through breakdance. A lifestyle they fight to preserve every day.

0 Comments

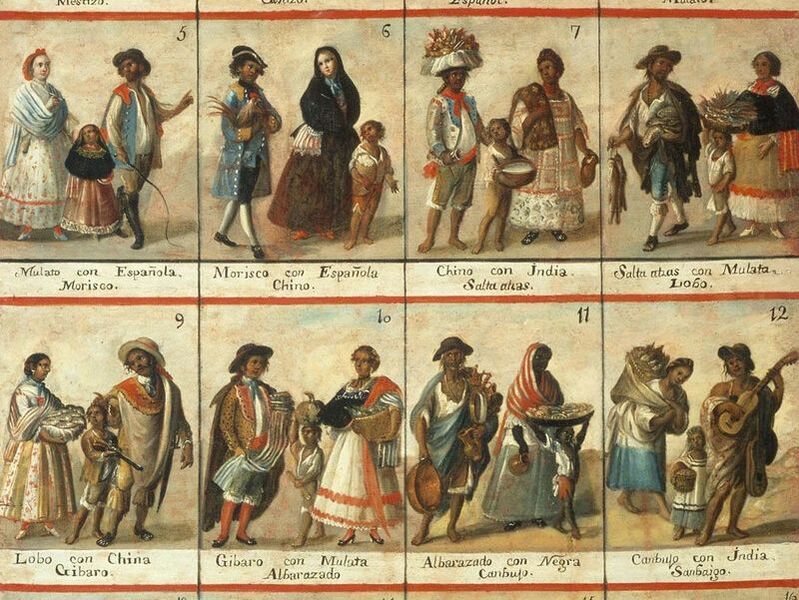

Why do we need the 'racialized' in 'racialized capitalism'?[1] In his recent article for Field Notes,[2] Charlie Post insists on the need to think racism and capitalism together but is keen to move the discussion 'beyond racial capitalism' perspectives[3] because of disagreements about the spatial and temporal origins of racism, and about the explanation those perspectives offer for the reproduction of racism in capitalist societies. While there is much to welcome in Post's carefully-crafted account, there are four areas of disagreement to which I want to draw attention. First, whatever substantive critiques one might wish to level at racialized capitalism perspectives, it is premature to speak of going 'beyond racial capitalism' or to claim that 'the notion of 'racial capitalism' is redundant [because] there is no 'non-racial' 'capitalism,' without a more thorough consideration of the political and theoretical work these perspectives perform in the present moment. Post certainly acknowledges that they emerged out of the reverberations of collective action against state racism, particularly the desire of a new generation of activists to make sense of racism's continuing power to inflict damage and death. However, there is much more that needs to be said on the matter. In particular, racialized capitalism perspectives help make transparent the constitutive role racism played in the formation and reproduction of capitalist modernity. This is no mean achievement, given that much of public discourse, along with liberal and critical thought, continues to minimize and underestimate its structuring power and significance.

If we look at it sociologically, we see that blood has been associated with a spectrum of positive and negative qualities, from being a symbol of sacred bonds to outright impurity. Blood represents family ties, contains codes and data about our physical health and wellbeing, and is also pervasive in religious symbolism. The blood of a martyr or Messiah represents some truth about salvation, and the relation between humans and the divine.

My Identities article, ‘Could we use blood donation campaigns as social policy tools?: British Shi’i ritual of giving blood’, investigates the socio-cultural settings behind a nationwide blood donation campaign in the United Kingdom, the Imam Hussain Blood Donation Campaign – or in brief, IHBDC. The IHBDC was founded in Manchester by a few young Shia Muslim university students. Almost fourteen years after its foundation, IHBDC is one of the largest cross-ethnic blood donation campaigns collaborating with NHS Blood and Transplant, in England, as well as the Scottish National Blood Transfusion Service (SNBTS). The community activists see this campaign as a way of honouring the sacrifice of their martyr and spiritual leader, Imam Hussain, as well as addressing a health-related social problem. As there is a difference in the frequency of blood types between different ethnic groups, in an increasingly multi-ethnic society, activists are needed to take on the responsibility of assisting with balancing the blood stock level at any given time. The conjunction of religious mythology of blood and donation activism has proved to be effective. Activists are getting more political recognition for their community, while contributing to tackling a social problem. The clearest mark of such recognition is the passing of motions supporting the campaign in both the London and Scottish Parliaments.

The latest evidence of Europe’s anxieties about immigrant (non-) integration comes in the form of a draft declaration released by Germany, France and Austria in November 2020. The declaration pushed for stricter EU integration rules, stating, ‘It needs to be possible to sanction sustained refusal to integrate more strongly than has been the case to date’.[1] Yet, each European country has always had a wide scope for determining how to admit and incorporate new members, and countries have not refrained from introducing strict measures. The latest trend is to start the integration process as early as possible – even before the migrant arrives, when traveling to Europe is just a dream. In recent years, France (2007), Denmark (2010), the UK (2011), the Netherlands (2006) and Germany (2009) have all introduced pre-integration measures for nationals of certain countries.

In my Identities article, ‘Cultivating membership abroad: Analyzing German pre-integration courses for Turkish marriage migrants’, I examine the aims and methods of German pre-integration courses offered to Turkish marriage migrants in Istanbul. Using participant observation and in-depth interviews, I also examine instructor perceptions and student reactions to the curriculum.

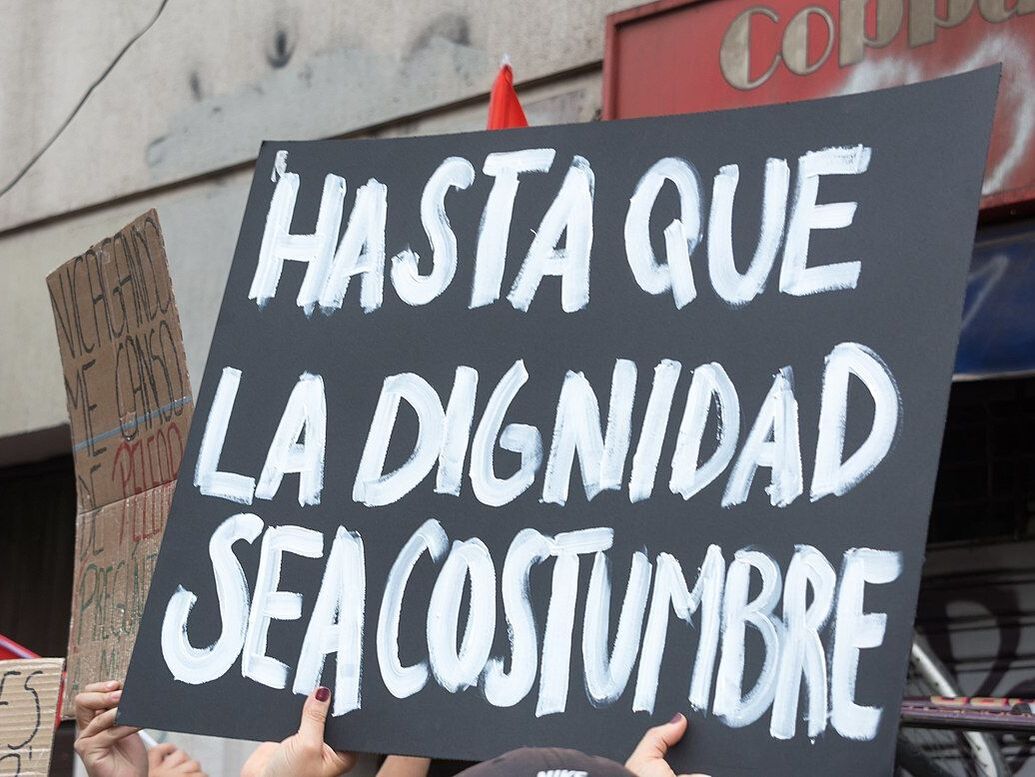

While writing our Identities article, ‘Disjunctive belongings and the utopia of intimacy: violence, love and friendship among poor urban youth in neoliberal Chile’, we had already started to witness a series of protests that recently culminated in the so-called Chilean ‘social outburst’ in October 2019 and the current process building a constituent assembly. Issues of quality of education, environmental concerns, shortcomings in the social security system, as well as long-standing efforts for the cultural and political recognition of indigenous groups gained increasing support over time. Yet, the many protests still appeared geographically scattered, and while people in the urban margins indeed felt uneasy with their life prospects, it was still uncommon to hear people articulate a more thorough critique of the neoliberal model that has prevailed in Chile for the past forty years.

In Los Acantos, the residents we met in 2012–2013 were conscious of these issues. Many of the young residents we met saw no way out in a world bounded off by invisible borders of social (in)difference and stigma. People were, in other words, aware of their almost impossible odds of socio-economic mobility and underneath the surface of monotonous low-income houses, the attentive ethnographer could feel the discontent. |

|

Explore Identities at tandfonline.com/GIDE |

|

The views and opinions expressed on The Identities Blog are solely those of the original blog post authors, and not of the journal, Taylor & Francis Group or the University of Glasgow.