|

|

|

While writing our Identities article, ‘Disjunctive belongings and the utopia of intimacy: violence, love and friendship among poor urban youth in neoliberal Chile’, we had already started to witness a series of protests that recently culminated in the so-called Chilean ‘social outburst’ in October 2019 and the current process building a constituent assembly. Issues of quality of education, environmental concerns, shortcomings in the social security system, as well as long-standing efforts for the cultural and political recognition of indigenous groups gained increasing support over time. Yet, the many protests still appeared geographically scattered, and while people in the urban margins indeed felt uneasy with their life prospects, it was still uncommon to hear people articulate a more thorough critique of the neoliberal model that has prevailed in Chile for the past forty years.

In Los Acantos, the residents we met in 2012–2013 were conscious of these issues. Many of the young residents we met saw no way out in a world bounded off by invisible borders of social (in)difference and stigma. People were, in other words, aware of their almost impossible odds of socio-economic mobility and underneath the surface of monotonous low-income houses, the attentive ethnographer could feel the discontent.

Analysing how young people inhabited those social realities, we developed the concept of ‘disjunctive belonging’. We did not want to describe our interlocutors as situated ‘outside’ of social order. We wanted to make sense of the struggles and possibilities that young residents in Los Acantos saw whilst dwelling in place in which social relationships were structured by the ever possibility of violent outbursts, scant of opportunities for upward mobility, and the incentives of a parallel – and more profitable – drug economy. We saw how our interlocutors’ experiences were informed by a sense of paralysis and feeling stuck in their impossibility to imagine and act upon the future. ‘A life built upon accidents’ was how one young interlocutor brilliantly summarised it for us. But still, the all-invading experience prevailed. Reality as it is could not be changed: we would not only need to ‘simply’ have to adapt to the imperfect neoliberal democracy that had replaced a horrendous dictatorship. The urban poor (and other marginalised groups) would have to carry the burden and the shame of not fulfilling their part as successful citizens in the ‘Chilean miracle’.

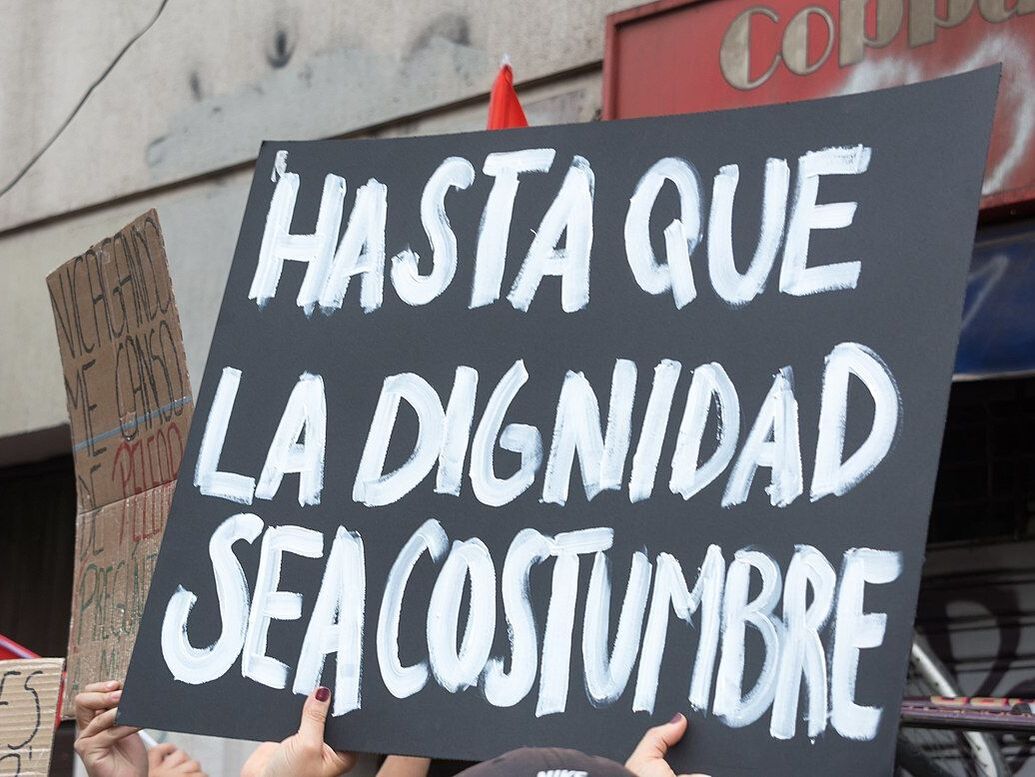

Struck by the seeming obligation to endure rather than flourish, we sought to understand the lateral movements people would make to dream and actualise a precarious, virtual version of themselves that could be more satisfying for themselves. Participants used the neoliberal rhetoric of wilfulness to make sense of the cases in which some ‘exceptional people’ could remove themselves from the neighbour's self-perpetuating dynamics and move on. We understood this in terms of the neoliberal logic of ‘pulling yourself by the bootstraps’ that has informed social mobility dreams across the Americas. Writing the ethnography, we tried to let these subtle tensions shine through. And yet, there was something in the making that we can only see from the hindsight. The years 2019 and 2020 saw Chile shaking again with an intense, sometimes violent, and large-scale mobilisation. Chileans’ multiple discontents with ‘the model’ were coalescing. Many people in Chile were euphoric and the protesters chanted over and over again that ‘Chile has awakened’. After months of protests, a parliamentary agreement was reached to change the country's political constitution – one that had been designed during the military dictatorship almost 50 years ago and merely amended since then. In a referendum, millions of people turned up to show overwhelming support for the option to start a participatory process of decision-making from scratch; a process whose outcomes will need to be later ratified in a second popular vote. The suspense we feel about the unfolding of this story leads us to end with a short reflection on ethnographic writing. When writing the conclusion of our Identities article for a special issue dedicated to the topic of youth and utopia, Ignacia, as an early career researcher and co-author, struggled to understand where hope lied therein. Yet, we had to embrace the theme; it was at the core of the special issue. Helene then suggested adopting what Ignacia remembers as ‘the fishtail model’ in which the article's conclusion did not need to be tight but could open itself to other possibilities and potential readings of the present. The rationale behind the ‘fishtail model’ was, according to Helene, that we did not need to foreclose the unfolding of people's worlds in our writing. Los Acantos residents' attempts to humanise their worlds were still utopian: there were trying to live otherwise. Hanging on the idea of an open fishtail, we finished revising the article hoping that the experiences of those living in the Acantos could be re-written too. We tried to remain open and recognise the simmering language of social critique and its potential for social transformation. We wanted to give some credit to a politics of care that goes beyond the fragile illusion of individual realisation through romantic love. Maybe now, while the entry-point referendum has been supported, we might be able to undo some of the ‘social debt’ undermining the Chilean poor. But again, we can only end with a ‘fishtail’ at this point, hopeful but also painfully aware of the limits. Neither will the historic criminalisation of the poor be swiped away overnight, nor will the very real structural and criminal violence that affect their lives vanish ‘just’ because a new constitution. Yet, we dare to hope because people have dared. We leave it open, trying to not over-determine what is at stake.

Blog post by Ignacia Arteaga, Cambridge University, UK and Helene Risør, Universidad Católica de Chile, Chile

Read the full article: Arteaga Pérez, Ignacia & Risør, Helene. Disjunctive belongings and the utopia of intimacy: violence, love and friendship among poor urban youth in neoliberal Chile. Identities: Global Studies in Culture and Power. DOI: 10.1080/1070289X.2017.1400278

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

|

Explore Identities at tandfonline.com/GIDE |

|

The views and opinions expressed on The Identities Blog are solely those of the original blog post authors, and not of the journal, Taylor & Francis Group or the University of Glasgow.