|

|

|

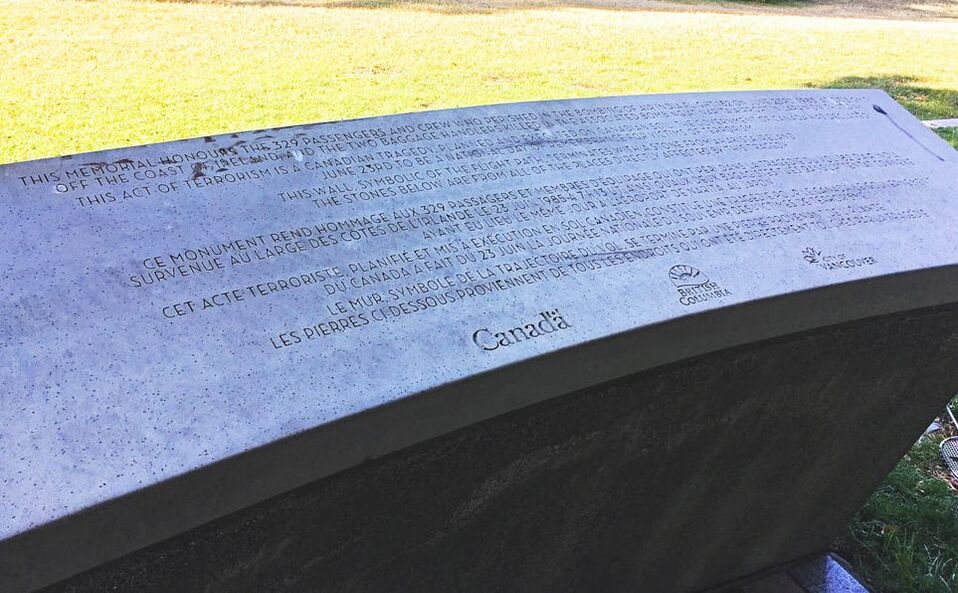

In June 1985, 331 people were killed in the bombings of two Air India flights, which investigators attributed to militant Sikh nationalist groups operating in Canada. Although the bombings are now regarded as the deadliest incident of terrorism in Canadian history, they continue to hold a complex, often contradictory place in Canada’s imaginary.

Much of the existing scholarship has attributed this complexity to systemic racism that limits how the bombings have been regarded and remembered as a ‘Canadian tragedy’ (Dean 2012, Failler 2009, Seshia 2012), even as the Canadian government devoted considerable resources to investigating and prosecuting the attacks. In 2006, the Government of Canada even commissioned a public inquiry to determine how state institutions failed to prevent and effectively prosecute the bombings. Given that the inquiry received evidence that systemic racism shaped state responses to the bomb plot, it offers a unique vantage point to examine how state institutions reckon with their implication in racial violence.

0 Comments

In the summer of 1998, 300 Kurdish refugees landed at the Ionian coast and received help from the local inhabitants of Riace, a small Calabrian town. Ever since, refugees have been hosted in houses that were abandoned by local emigrants looking for work abroad or elsewhere in Italy, and leaving behind an impoverished ‘ghost town’. Over time, local NGOs and the municipality have developed a comprehensive settlement programme for up to 400 refugees at a time. Refugees, in turn, bring new life into this once-dying town, and the settlement programme is combined with projects aimed at the socio-economic revival of the local community [1]. Curious to find out whether the welcoming attitude towards refugees (Sasso 2012) was genuine and how the support for them was generated, the first author of the Identities article, 'Local identity and the reception of refugees: the example of Riace', decided to live in one of the abandoned houses for a period of 5 months.

Through the ethnographic fieldwork of the first author, we soon found out that there are various economic, demographic and political factors underpinning the success of Riace’s reception programme. The article being discussed aimed to examine how the people in Riace created and enact a local identity of hospitality. In the article, we analysed the type of ‘identity work’ that the Riace inhabitants and local leaders are involved in. Far-right politics and anti-immigration parties often present refugees as a threat to the local identity due to their different cultural or religious background, and a strong national identity regularly goes together with the rejection of newcomers (Bansak et al. 2016). Theoretically, social identities are often conceptualised in terms of group boundaries and processes of boundary drawing (‘who belongs to us’; Wimmer 2009), but they also define specific norms, values and beliefs of ‘who we are as a community’. The case of Riace shows that when the content of the local identity is pro-social and a community defines itself in terms of hospitality, community members are inclined to act, think and feel in that way (Reicher et al. 2010). In agreement with this ‘social identity perspective’, our research demonstrates that a strong local identity can go together with the inclusion, instead of the exclusion, of newcomers.

Interviewer: ‘What do you think it means to be British?’

Miriam: ‘It is a passport. To be British now, I’m sorry to say this, but it is a passport. That is it. That is what being British means to me… I have lost faith in the country which I used to call home. I have lost faith, I have lost trust. Every single bit of pride that I had to be calling myself a British citizen has almost gone out of the window. They have basically sucked every single bit of love for the UK out of me.’ Miriam’s story Miriam’s husband had been in the UK from his teens but was recently forcibly removed from the country, after a traumatic period incarcerated in immigration detention. The authorities have advised Miriam that she should choose between staying in the UK alone or leave to be with him. She’s choosing the latter: ‘I just said stuff it, if England don’t want me to live here, I will live in any country in the world with him, and that is it.’

Haymarket/Chinatown is a precinct located in the southern end of Sydney’s Central Business District. The precinct has become part of the City of Villages initiative, promoted by the City of Sydney administration to inject dynamism in the local economy based on the belief that the city is made up of diverse marketable areas, each endowed with a unique identity. Unlike the other precincts in the Inner Sydney area, the point of differentiation chosen for Haymarket/Chinatown is ‘ethnicity’ — more precisely, an ambiguous multi-Asianness within which images of Chinese communitarian identity occasionally emerge to confer a sense of authenticity to the ethnic place brand.

In my Identities article, ‘Ethnic community in the time of urban branding’, I observe how these simplified images of ‘groupist’ (Brubaker 2002) Chinese identity emerge from the brand management strategy for the Haymarket/Chinatown precinct despite the diversity of the local business and resident community. I frame these instances as tensions inherent in the process of place branding, which is characterised by the need to essentialise for marketing purposes while grappling with increasing levels of cultural complexity of the most populous Australian city. 25 years after apartheid: are British-born South Africans signing up to the ‘rainbow nation’?2/10/2019

2019 marks 25 years since Nelson Mandela was elected as the first black president of South Africa. Finally, apartheid, the system of racial segregation institutionalised by the Afrikaans-led Nationalist Party in 1948, was a chapter closed. Since that time, South Africans of all backgrounds have been debating the extent to which the post-apartheid vision of ‘a rainbow nation’ -- a multicultural unity of people of many different nations -- is being realised.

This question is not only of interest and importance within South Africa. Against a context of rising populism and white nationalism across the Global North, are white people in South Africa really rejecting the privileges of white supremacism which they have enjoyed for so long? My Identities article, 'Reimagining racism: understanding the whiteness and nationhood strategies of British-born South Africans', examines this question by looking at one group of South African Whites: those who were born in Britain and migrated to South Africa. Many did so in the 1960s, 70s and 80s, through a ‘Ten Pound Pom’ scheme which offered them cheap passage, good jobs and comfortable accommodation on arrival. Whereas, at home in Britain, there was rising rejection of the apartheid system in South Africa, this group chose to up sticks and move to a deeply segregated society. How do they explain this, to others and themselves? And how do they now talk about the situation in South Africa today? |

|

Explore Identities at tandfonline.com/GIDE |

|

The views and opinions expressed on The Identities Blog are solely those of the original blog post authors, and not of the journal, Taylor & Francis Group or the University of Glasgow.