|

|

|

Transnationalism is a fundamentally agentic concept. Emerging as a critique to methodological nationalism, it emphasises processes that occur between, beyond – and often in defiance of – the boundaries of the ‘nation state’. Applied to international migration, it stands as a dominant paradigm for framing sustained economic, social and cultural ties maintained by migrants across international borders, and enduringly celebrates the agency of transmigrant actors with fluid connections to countries of origin and destination.

Our Identities article, 'Forced transnationalism and temporary labour migration: implications for understanding migrant rights', takes a very different view of transnationalism. We suggest that, while the tone-setting ‘first wave’ of the transnationalism literature offered an important critique of assimilationist immigration regimes in the global north, its agentic emphasis had little resonance with highly-restrictive guest-worker migration prevalent across the global south – particularly the major migration corridors of Asia. In these settings, state power was then, and still is now, pivotal in circumscribing the transnational existences of millions of migrant workers who emigrate out of economic necessity but are trapped between multiple political and economic interests that ensure their migration is strictly temporary. Though scholarship on transnationalism has typically shied away from defining these temporary labour migrants as transmigrants on account of the narrow scope of activities presumed to be carried out by the remitting labourer, this seems disingenuous.

0 Comments

Migration, like all social issues, is an ever-evolving phenomenon. Recently, the COVID-19 pandemic, the rise of extreme right-wing politics worldwide and the economic and ecological crises, among others, further add to those identified in our Identities article, 'Interwoven migration narratives: identity and social representations in the Lusophone world', published a few years ago.

Surely, the field of Migration Studies demands a constant examination of social changes and, among other things, how they intersect with and influence migration flows and migrants’ life experiences. However, it is important to stress that, alongside new representations of the world and its power dynamics, there are long-standing ones. From the perspective of the Humanities and Social Sciences, it is crucial to understand the ruptures, continuities and accommodations of social representations and the effects these have in shifting or maintaining the status quo. To this end, the argument of our article provides a useful framework to situate the analysis of migration narratives. Specifically, we present three elements of enduring discursive constructions and social representations of commonality among the Portuguese-speaking countries: the ideas of a shared past; a common language; and a sense of community, marked by hybridity and deep cultural ties. Aiming to contribute to the understanding of how deep-seated these ideas are, we explored the intersections, reverberations and clashes of these dominant ideas of Lusophony in migrants’ life narratives, understood as tools to explain, organise and frame the world as well as to make sense of one's self-identity. Automatic transmission: how cars help us understand the dynamics of race and racialisation16/12/2020

In my Identities article, ‘Automatic transmission: ethnicity, racialization and the car’, I discussed how various types of racism can be transmitted through cars and roads, and feed into driver behaviour. While this can result in racial discrimination operating in formal and legal contexts, such as policing, racialisation through cars has a much broader, and at times, arguably banal, normative and taken for granted presence and reach.

In ethnically diverse towns and cities in the UK, when expensive cars are driven by young non-white males, what appears to be ordinary (driving and cars) becomes subject to racialised logic – that certain behaviours are tied to what become normative expectations of the ethnic group in question. In part, this happens because of what cars do and do not signify, but also, of course, this hinges on existing codes, stereotypes and ways of perceiving and explaining the idea of race, and all that flows from it. Earlier in 2020, we learnt that a number of prominent Black Britons, including MP Dawn Butler, had experienced, and subsequently spoke out about, racist policing. As distressing as such events are they are not particularly unusual; every day, black bodies are subject to similar, and worse, attention from law enforcement. In some cases, of course, the police may well have legitimate grounds to pull over a suspect, but often, it is the marker of race that helps prompt or even provoke the intervention.

The recent Black Lives Matters (BLM) protests offer a juncture for Britain to have a broad and sensible conversation on race and racism, similar to that headed by the Clinton administration in America 20 years ago. The recent re-appearance of the debate on terminology – the question of how to refer to racialised groups in Britain – may be the beginning of this. It is not a new question but is being posed by a new generation of Black Britons, who having been born in the UK should be unfamiliar with Hall’s sense of living ‘on the hinge between the colonial and post-colonial worlds’ (Hall & Schwarz 2017, 11).

In my Identities article, ‘The stigma of being Black in Britain’, I argued that despite more than 50 years since Britain adopted its first Race Relations Act (1965), colour remains a ‘visible feature of the urban landscape’ (Hall & Schwarz 2017, 184) in the UK. I described Brexit as an indication that, as Stuart Hall wrote many years ago, many of the ‘white underprivileged…believe that what they experienced was not because they were poor and exploited but ‘because the blacks are here' (Hall & Schwarz 2017, 185).

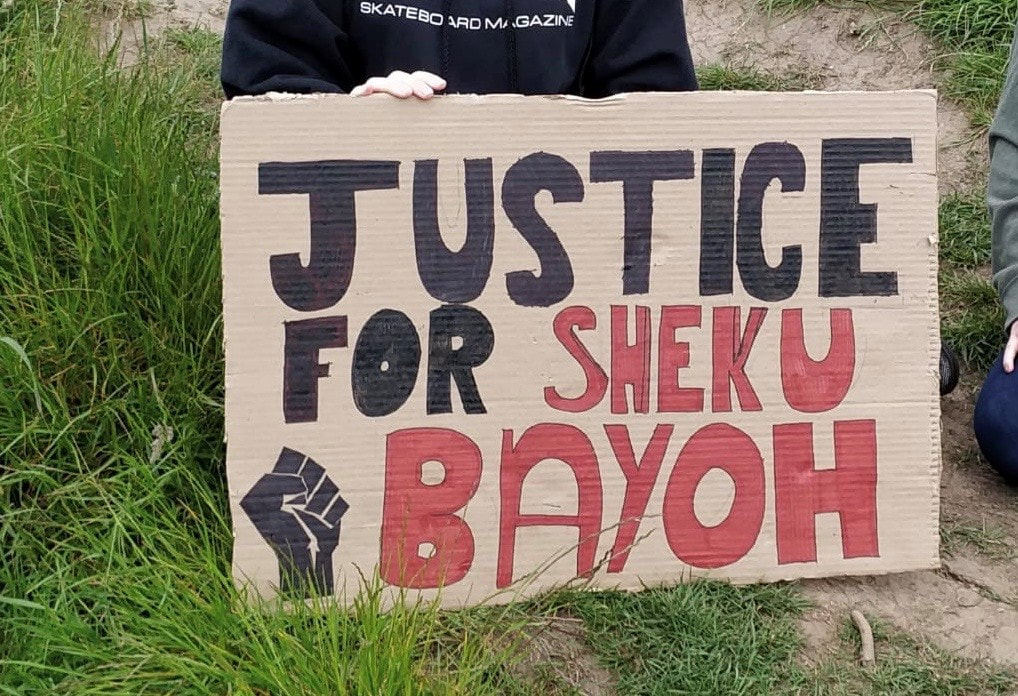

Sheku Bayoh died shortly after he was arrested by up to nine police officers in the early hours of 3 May 2015 on a quiet street in Kirkcaldy, a small town on the east coast of Scotland. Sheku’s mother had encouraged him to move to Scotland to be near his sister because she thought a young black man would be safer in Scotland than in London. CCTV footage has shown that Sheku was on the ground and restrained within less than a minute of police officers arriving, yet the postmortem revealed he had 32 injuries to his body. The Lord Advocate of Scotland announced in November 2019 that no police officer would be charged for Sheku’s death, four and a half years after Sheku died.

I wrote my Identities article, 'Containment, state racism and activism: the Sheku Bayoh justice campaign', not only to shed light on the circumstances of how Sheku died after he was arrested but to attempt to explain why deaths in police custody happen, why they are disproportionately of black people, and to develop an understanding of why the families who have lost loved ones find it so hard to get justice or even an adequate explanation from the police of why. I argue that the state has an interest in containing working class struggles and that state racism is used as part of the containment strategy that explains black deaths in police custody. I use a historical and theoretical analysis of how racism has been deployed by the state in immigration legislation where the black presence was problematised. The problematic black presence discourse has historically been a key feature of the policing of black communities – although this has evolved in several ways it nevertheless continues to produce a racial criminalisation of black people. |

|

Explore Identities at tandfonline.com/GIDE |

|

The views and opinions expressed on The Identities Blog are solely those of the original blog post authors, and not of the journal, Taylor & Francis Group or the University of Glasgow.