|

|

|

For some migrant farm workers, exiting their state-approved contracts can provide an everyday means to refuse poor working conditions and evade coercive immigration and employment controls that are endemic to the agricultural streams of Canada’s Temporary Foreign Worker Program. Exiting their employment, an action that workers refer to as ‘escape’, puts at risk their right to legally reside in Canada.

However, in my Identities article, '"Escaping" managed labour migration: worker exit as precarious migrant agency', I examine how workers’ first-hand depictions of ‘escaping’ employment reveal new insights into how workers may claim a space of belonging that contradicts their experiences of status-based vulnerability. By leaving the farm and by extension Canada’s state-managed labour migration regime, workers are both refusing a life of precarity and embracing an unknown future where hope and chance may reveal a happier and more desirable life.

0 Comments

Being international, open and cosmopolitan is ‘cool’. This is specifically true for students at elite universities, where values such as multiculturalism and cosmopolitanism are promoted and enhanced by diversity-related activities and spaces. But what do students actually mean when they self-identify as cosmopolitans or global citizens? Do they all mean the same thing (probably not)? And what role does cosmopolitanism actually play in their lives?

My research, as explored in my Identities article, 'Exploring disjuncture: elite students' use of cosmopolitanism', is based on 24 interviews with international students at a global university in the UK. Its main finding is a typology of four different ways in which students use the idea of cosmopolitanism. To fill this typology with life, I introduce the reader to Jing, Shigeki, Faisal and Anna. Each of these four students represents one of the four ways in which my respondents made sense of cosmopolitanism.

I am sitting in the office of a refugee support and advocacy organisation in north-England to interview a refugee about her experience. The focus of our conversation is not on why Faith fled her country or how the charity helped her integrate in the UK. Instead, we talk about how she started working as a caseworker for one of the main refugee third sector organisations. When Faith walks into the office, people might think she is a client waiting for an appointment. They might initially be surprised when she sits down on the other side of the desk as they fail to recognise her as the professional worker that she is.

Stories about refugees and employment tend to highlight the significant obstacles in accessing the labour market (Kone et al. 2019). Lack of recognition of qualifications and home country work experience, short-term interventions by job agencies and language barriers all contribute to unemployment and deskilling. Many professionals end up in manual jobs in factories, catering or care. Refugees are overrepresented in so-called ‘3D jobs’; those that are Dirty, Dangerous and Degrading. Or they find work in 'ethnic niches', segments of the labour market with an overrepresentation of certain ethnic groups, such as the taxi industry or Ethiopian and Afghan restaurants. In my Identities article, ‘A window of opportunity? Refugee staff’s employment in migrant support and advocacy organizations’, I present the findings of my research into a very distinct employment 'niche' for refugees: the niche constituted by organisations that have asylum seekers and refugees as their client group. Based on interviews with refugee staff in the UK, the Netherlands and Austria, I argue that the concept of 'ethnic niche' fails to capture the particularities of the employment opportunities offered by the refugee third sector.

'First, I'll need tenure. And a big research grant. Also access to a lab and five graduate students — at least three of them Chinese.'

- Professor Ogden Wernstrom, Physicist Those are Professor Ogden Wernstrom’s demands when asked to save the Earth from a giant garbage ball approaching through space in the Futurama episode, A Big Piece of Garbage. Portrayed as an obvious antagonist, Wernstrom seems greedy and exclusively concerned with his own career advancement. He also seemingly regards grad students as just another commodity to further his own goals, with Chinese students as particularly valuable or useful assets. This specific view on Chinese researchers as not much more than pricey pieces of high-tech equipment was provided by a cartoon villain 20 years ago, but it arguably still falls into the questionable category of 'it’s funny because it’s true': it indeed resonates with prejudices that extend beyond the Futurama universe and into real-world academic discourse.

In recent years border walls have been built in different parts of the world in order to stop irregular migration. However, barriers for migrants are not only constructed physically but also discursively in political discourses. It is known that restrictive policies in Europe are accompanied by exclusionary discourses on national citizenship for immigrants, depicting them as either ‘deserving’ or ‘undeserving’.

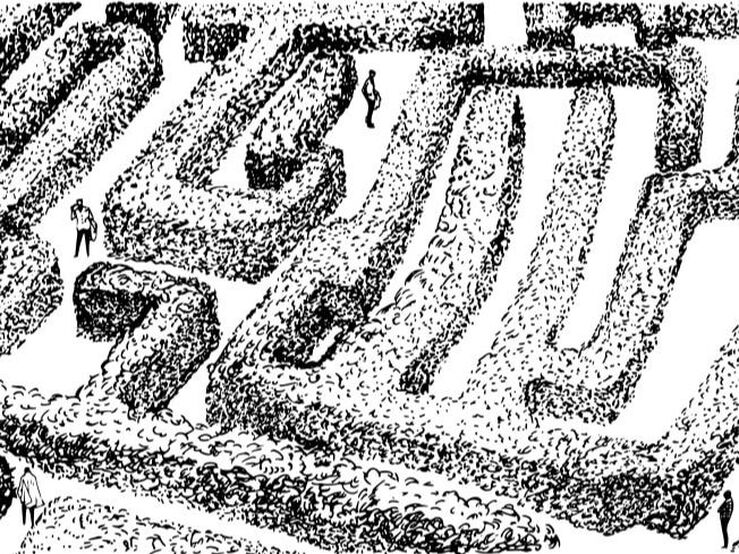

Empirical studies have demonstrated that the representation of immigrants and their citizenship in policies plays an important role in how these policies are received and acted upon, both by the host community and the immigrants themselves (da Lomba 2010; Stewart and Mulvey 2014). As such, studying political discourses might contribute to the understanding of the socioeconomic and political incorporation of immigrants into the host community. In the study presented in my Identities article, 'The labyrinth towards citizenship: contradictions in the framing and categorization of immigrants in immigration and integration policies', my co-author and I aimed to fully grasp how immigrants were framed in immigration policies in Belgium. Although previous studies have treated immigration and integration policies as distinct fields, we argue that a combined analysis of these two policy domains is needed in order to comprehend the full complexity of immigration policy. By mapping the different representations of immigrants in the wider policy field, we found that this is much more complex than the generally adopted contrast between deserving and undeserving suggest. |

|

Explore Identities at tandfonline.com/GIDE |

|

The views and opinions expressed on The Identities Blog are solely those of the original blog post authors, and not of the journal, Taylor & Francis Group or the University of Glasgow.