|

|

|

Blog post by Aino Korvensyrjä, University of Helsinki

In the first week of May 2018, there was some moral panic in the German media. National and regional media reported on a ‘mob’ of 150–200 black Africans violently stopping deportation and attacking the enforcement patrol in a reception centre for asylum seekers in Ellwangen, Baden-Württemberg. After the 2015 ‘Summer of Migration’, when popular sympathies for refugee-migrants had peaked in Germany, such narratives of dangerous black and brown refugee-migrant men were a standard feature in the German media and public debate. This continuous panic created public acceptance of deportations of asylum seekers and the increasingly ruthless control policies at external EU borders. My Identities article, ‘Criminalizing black solidarity: Dublin deportations, raids, and racial statecraft in southern Germany’, looks beyond the media and policy debate on ‘Ellwangen’. It examines how the police and courts managed local conflicts over deportation during an intense campaign to increase so-called Dublin deportations. These are deportations to the first country of entry in Europe. For the authorities, a fingerprint registered into the EURODAC database by another European country is enough to begin the deportation proceedings. West Africans were then a key target group of Dublin deportations, and Italy was the main country of destination. The article draws attention to a series of police raids targeting West African migrants living in southern German asylum camps in 2018, including the above-mentioned raid in Ellwangen. In all cases, police accused West African men of rioting against deportation enforcement to Italy, and local courts prosecuted numerous individuals. My article explores how the police and local courts thus suppressed anti-deportation protests and how their practices produced race.

0 Comments

Blog post by Sebastien Bachelet, University of Manchester, UK and Mariangela Palladino, Keele University, UK

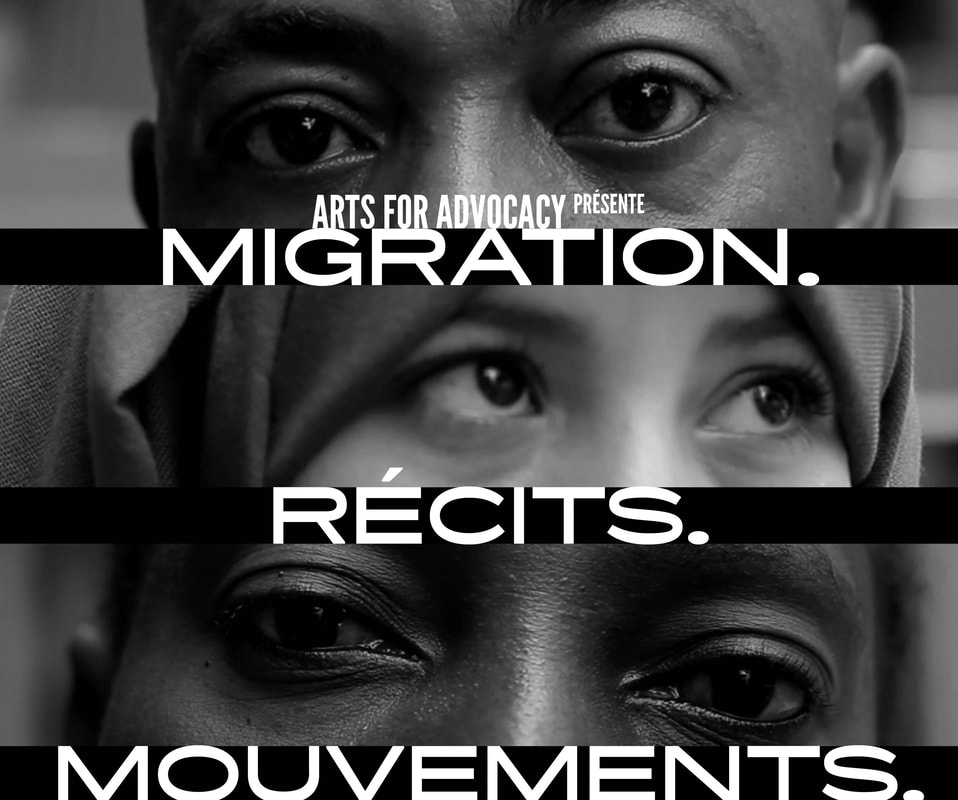

Overcrowded boats capsizing in the Mediterranean Sea feature regularly in the news. Yet, the discrepancy in the coverage and rescue efforts deployed for the boat carrying 750 people seeking safety which sank off the Greek coast, and the fate of the Titan submersible, is a stark reminder that vividly illustrates how some lives are more grievable than others. Talks of a migration ‘crisis’ moreover overlook the responsibilities and effects of European states’ hostile migration policies and violent bordering regimes. Public debates seldom scrutinize the political construction of migrants as illegal and undesirable, nor do they provide sufficient insights into people’s lives beyond abstract labels, especially south of the Mediterranean Sea, where European politicians propose to build asylum-processing centres. In this blog post, drawing on our Identities article, ‘Être vraiment vrai’: truth, in/visibility and migration in Morocco’, we focus on migration, creative processes and advocacy in Morocco, to demonstrate how narratives of migration that challenge expectations and demands for authentic and truthful migrants’ accounts can disrupt dominant and harmful forms of representation.

Blog post by Emiliana De Blasio, LUISS University, Italy, Marco Palillo, University of Bradford, UK and Donatella Selva, University of Florence, Italy

Over the last decade, the Mediterranean Sea has become one of the deadliest migration routes for asylum seekers and migrants wanting to reach Europe from Libya. In response to the high numbers of deaths associated with perilous journeys and dangerous smuggling strategies, numerous non-governmental organisations (NGOs) have been operating in the Mediterranean Sea to provide search and rescue (SAR) operations to migrant vessels in distress at sea. Over the years, the new centrality of NGOs’ humanitarian efforts in the Mediterranean Sea in the Italian public and media discourse has led to significant tensions with right-wing parties. Most notably, Matteo Salvini’s League and Giorgia Meloni’s Brothers of Italy have repeatedly criticised NGOs involved in SAR operations for facilitating irregular migration flows and defying Italian border control policies. Since its inauguration in October 2022, the newly installed government led by Giorgia Meloni has engaged in a series of clashes with NGOs running SAR operations in the Mediterranean Sea as part of the government’s hard-line stance on ‘illegal’ migration. In particular, Meloni’s government has promoted a new migration policy that introduces further restrictions on the capacity for NGO vessels to conduct multiple rescues in the same mission.

Around 9.30am on Thursday 13 May I checked my phone for messages, as I was about to start making preparations for Eid dinner later that evening. One of the No Evictions Network activists had posted a photo of an immigration enforcement van in Kenmure Street in Pollokshields and said that he was going to investigate what was happening, and asked others in the network to come down to support him. As more and more members of the network arrived, it transpired that immigration officers had raided the home of two men, Sumit Sehdev and Lakhvir Singh, and put them in the van. The immigration van couldn’t leave because it was surrounded by activists, and one of them had got under the van (and would stay there for eight hours to ensure it wouldn’t go anywhere). Activists reported that Police Scotland were helping immigration officials by trying to persuade the activists to disperse. In solidarity, thousands of Pollokshields locals as well as people from across the city gathered to prevent this immigration raid. The two men, both migrants from India, were eventually released.

Throughout the day I was reading news reports and comments on social media about how friendly and welcoming the people of Glasgow are to newcomers, as if that was enough explanation for the overwhelming solidarity against this particular immigration raid. Whilst Glasgow has a reputation for being friendly, it also has a history of racism going back to the days of empire and the attacks on black seamen in 1919. I also read reports crediting the release of the two men to the actions of individual activists. This is mistaken.

Have you ever thought about the way that language is used to frame our understanding of ourselves and other people? It wasn’t many years ago that public transport systems moved from calling people ‘passengers’ to ‘customers’ – a transition that reflects the privatisation of these services, and the now primarily economic nature of the relationship between the service user and provider.

On a global scale, we principally use the language of nation-states to frame self and other. These are not empty frames, but full of meaning, rights and responsibilities. Nation-states ascribe citizenship, enact power, arrange economies, provide healthcare and education (to varying degrees), determine freedom and influence (consider the power of a British passport over, say, an Iranian one), and control the movement of goods and people. But what happens when people challenge this nation-focused way of divvying up the world? How do we see the nationally non-compliant, and how does that influence how we ourselves are then framed? |

|

Explore Identities at tandfonline.com/GIDE |

|

The views and opinions expressed on The Identities Blog are solely those of the original blog post authors, and not of the journal, Taylor & Francis Group or the University of Glasgow.