|

|

|

Thanks to decades of critical scholarship in the social sciences, it is now common for scholars to reflect on their positionality vis-à-vis research topics and subjects and to demonstrate awareness of the power structures that shape their knowledge production. While this often amounts to deliberations about one’s individual identity in terms of race, gender, class, sexuality, ability, etc., scholars are rarely expected to question the ideological assumptions that underpin how they, both as individuals and as members of societies, make sense of the world. Taking certain ideological positions for granted as universal – liberal, secular, individualist, etc. - presents a problem in the study of political life-worlds that claim to offer alternatives, especially those with revolutionary system change on their horizon.

In my Identities article, ‘Stateless citizenship: 'radical democracy as consciousness-raising' in the Rojava revolution’, published in the special issue ‘Radical Democratic Citizenship: From Practice to Theory’, I write about ways in which protagonists of the self-determination system that has been in the making in majority Kurdish regions of Northern Syria since 2012 imagine their political struggles as a long-term effort for liberation from capitalism, patriarchy and the nation-state. I argue that this amounts to a decolonization effort that – in the words of my interlocutors – beyond the concrete work of building institutional infrastructure, aspires to transform dominant ‘mentalities in society’, including patriarchal and statist thinking which developed over thousands of years of power and domination. While sharing fragments from my fieldwork in Rojava, I decided to consciously center the ideology of the Kurdistan freedom movement, as articulated by imprisoned political leader Abdullah Öcalan, in my conceptual framework.

Cross-posted by RACE.ED

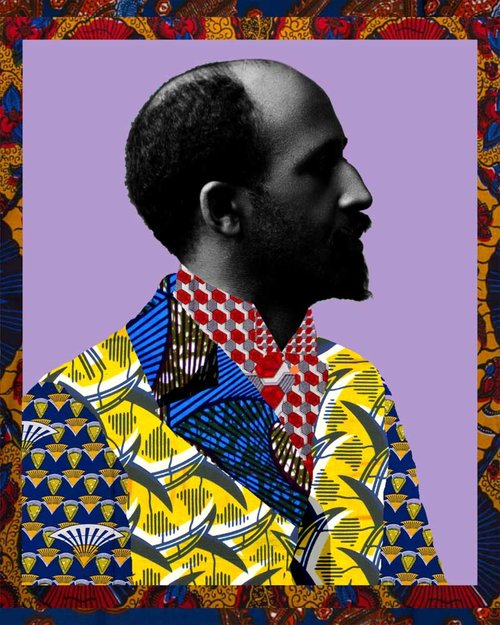

‘We are now in the age of Du Bois’, declared Aldon Morris in his widely acclaimed study, The Scholar Denied: W. E. B. Du Bois and the Birth of Modern Sociology. In this, Morris meticulously charts the intellectual contribution of Du Bois (1868-1963) to the social sciences broadly conceived, and sociology in particular, to argue that this remarkable figure could no longer been treated as peripheral, or an ‘add on’. After all, few sociologists pioneered as much as Du Bois, including in, amongst other areas, both quantitative and qualitative methodologies, especially social statistics and urban ethnography, reconciling questions of political economy with social movements (not least in charting the suppression of Atlantic slavery), as well as foregrounding relationships between the self and society, and doing so in ways that prefigure questions later posed in the politics of recognition. For these reasons I am not alone in arguing that Du Bois has bequeathed to sociology a cluster of normative categories that compel us to move beyond a kind of formalistic inquiry, and through which we might be more open to uncovering sometimes submerged features of social life (1).

A number of different aspects of identity are relevant to young people, from self-esteem, distinctiveness, self-concept, clarity, coherence and self-continuity. We recently published a paper in the Journal of Social Psychology Research on the importance of the social context as a component self-continuity. Using young adults (ages 19-25) from the US and Brazil, our latest research demonstrates that the social context, specifically our friends and family, is a novel, measurably distinct self-continuity strategy. In particular, the results from our study exemplify that relationships continue to play an important role in healthy identity development.

Emerging adulthood refers to the period of early adulthood between the ages of 18 and 25. Specifically, it’s characterized as an age for exploring different identities, within the contexts of school, work and romantic relationships, to name a few. Due to the changing roles during this period of the lifespan, this is also an age exemplified by instability. Beyond that, emerging adults can feel in-between adolescence and adulthood, that this is a period of their lives to focus on themselves and that the future contains a range of possibilities for them. As such, this makes for a crucial period to study identity development.

Gender, as expressed on namely the bodies of Muslim women, is positioned at the centre of the radical right’s linkage between migration and religion. This link is visible in the persistent debates on the ban of Muslim body-covering, which in Austria has been promoted by the Austrian Freedom Party (FPÖ) since the turn of the century.

FPÖ’s debates on the ban of Muslim body-covering – of the headscarf in kindergartens and schools or of full body-covering in public spaces – which re-emerged since 2015, illustrate that the radical right instrumentalizes the intersection of gender, body and religion in its search for new forms of governing. As I explore in my recently published Identities article, ‘Radical right populist debates on female Muslim body-coverings in Austria. Between biopolitics and necropolitics’, the radical right’s debates over female Muslim body-covering are embedded in the neoliberal reorganisation of societies and a crisis of governability, which radical right-wing actors use to implement their own biopolitical and necropolitical projects. |

|

Explore Identities at tandfonline.com/GIDE |

|

The views and opinions expressed on The Identities Blog are solely those of the original blog post authors, and not of the journal, Taylor & Francis Group or the University of Glasgow.