|

|

|

Blog post by Christian Lamour, Luxembourg Institute of Socio-Economic Research, Luxembourg

Late modernity in the European Union is characterized by the return of ‘hot nationalism’, with a growing number of citizens supporting radical right parties and leaders. These political entities and personnel have hammered out an electoral winning, ‘nation-first’ agenda, which is notably marketed as protecting the cultural identity and cohesion of a national people, jeopardized by alien threats. This vivid return of national cultural identities in the agenda of European states has appeared at a time when relationships between EU member states have been remarkably peaceful for generations, whereas their main long-term heritage has been the reproduction of national conflicts, territorial gains and momentary stabilization of borders following treaties torn apart in subsequent wars. The cultural enemies defined by today’s EU radical right within specific nation states are not neighbouring nations, but communities, the identities of which are represented as external to the world of nations. This means the elites are characterized as Europeanized/globalized, whilst the non-European migrants are racialized as oriental/African entities replacing the European national identities with the support of the globalized elite.

0 Comments

Blog post by Siow-Kian Tan, Xiamen University, Malaysia

Food has the incredible ability to bring people together, yet it can also stir up debates over its origins. Dishes like Laksa, Nasi Lemak, Bak Kut Teh (BKT), Hainanese Chicken Rice and other local favourites have been passionately claimed as national dishes by both Malaysians and Singaporeans. This culinary dispute isn’t new. Back to 2009, Malaysia’s then-tourism minister, Ng Yen Yen, sparked controversy and patriotic fervour in both neighbouring countries by suggesting that Malaysian cuisine had been ‘hijacked’ by others. Each side adamantly defends dishes like nasi lemak, BKT and chilli crab as authentic and original, and criticizing the other of appropriating culinary heritage. However, are such disputes meaningful and can a dish genuinely belong to a single nation? In 2023, Channel News Asia’s ‘On The Red Dot’ programme delved into these questions, interviewing chefs, hawkers and heritage experts to uncover the origins and stories behind iconic dishes like chili crab, BKT, nasi lemak and cendol. Hosted by Ming Tan, a chef and culinary consultant, this captivating series explores how dishes evolve and travel across borders.

Blog post by Ece Yoltay, Ahi Evran University, Turkey

My Identities article, ‘Queering trialectics among space, power, and the subject: spatial representations and practices of othered identities in Turkey’, is grounded in a critical analysis of the Foucaldian conceptualization of the relation between power and the subject. It does so by examining the construction of the concept of ‘supra-identity’ with the Repressive and Ideological State Apparatus in Turkey. Since the Republic of Turkey was established as a nation-state in a predominantly Muslim society, various legal and social regulations determining state-citizen relationships have been shaped in its political history (single-party period 1923-1946, multi-party period 1946-2018, Presidential system 2018-present). While each government in this history produces its own political interpretation of the 'ideal' citizen, the emphasis on Turkish and Muslim identities, particularly within the heteronormative social structure associated with Islam, has been common value for defining ‘supra-identity’. In Turkey's multicultural society, homogenizing differences over these identity values of the 'majority' has been deemed necessary for the 'unity of the state'.

Blog post by Fatima Rajina, De Montfort University, UK

When we think about Muslim clothing, often our immediate thoughts turn to Muslim women and their sartorial choices. Much of this has been framed via the media because of its incessant coverage, focusing on many European countries and their legislation monitoring Muslim women's clothing choices. This very discussion is in the press currently, as France has banned wearing the abaya in schools for young Muslim girls. It is precisely this framing that made me think about where Muslim men fit into this equation. How do Muslim men choose what they wear in public? What informs their decisions? As a result, in my Identities article, 'British Muslim men and clothes: the role of stigma and the political (re)configurations around sartorial choices', I diverted from the fixation on Muslim women and interrogated the political imagination and (re)configuration of dress practices among British Bangladeshi Muslim men. I selected three attires, the lungi, the funjabi and the thobe, because of what they represent for Bangladeshis. The lungi and funjabi, although associated with Bangladeshis, carry different meanings in the diaspora than in Bangladesh. I explore how these two garments are worn in the UK and how they (re)appear in public. In contrast, the thobe projects an Islamic universalism not afforded to the first two garbs and carries a different form of visibility. I focus on how British Bangladeshis of varying age groups interact with different forms of attire and what it means for their identity negotiation in the public sphere.

Blog post by Vadricka Etienne, University of Nevada, Reno, USA

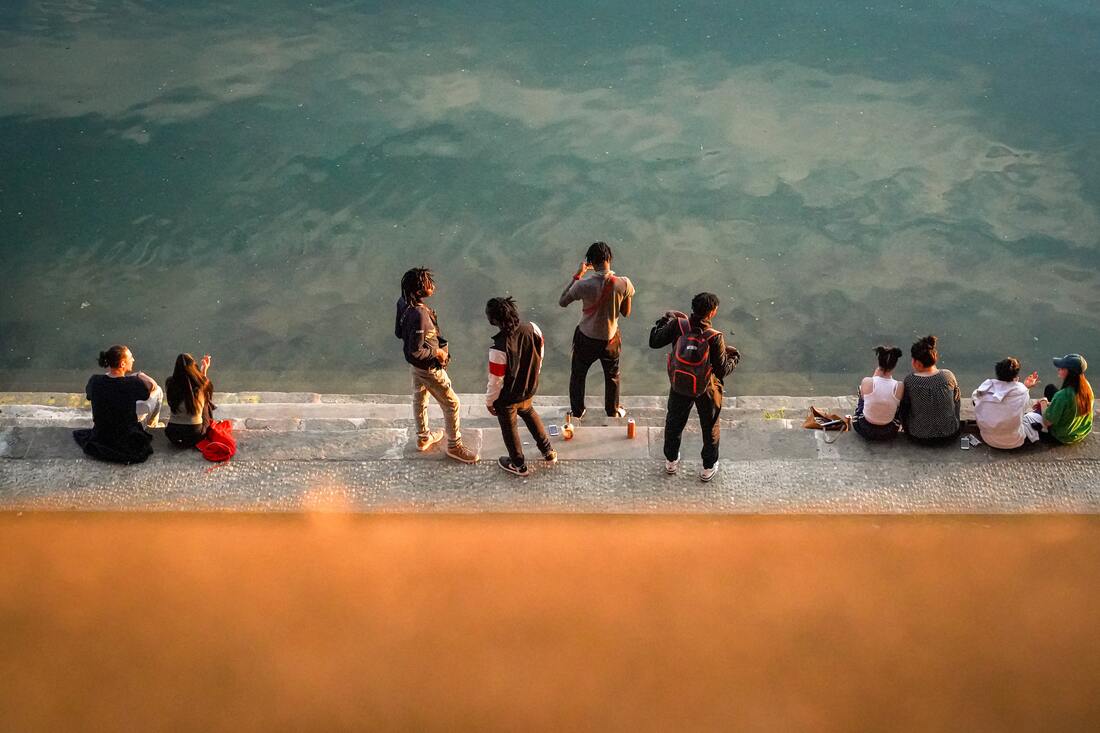

Each year, my immigrant father embarks on a summer trip to Haiti. A lump jumps into my throat as he prepares for his journey. He’s excited to return home, but I fear for his safety. This fear grows yearly, and my anxiety spikes whenever he doesn’t answer the phone. My thoughts race to the worst-case scenarios, mainly because we’ve discussed what to do if he was kidnapped. While the rising gang violence demanded that he skip his trip last year, he would not miss another. I understand because he is at peace when in Haiti. But I find myself taking deeper breaths only when he lands in Miami, making his way home. During the summer, I consumed conflicting media reports. Mainstream media catastrophized the gang terror, while Haitian content creators shared the mundane, such as dinners out on the town, demonstrating that the violence was not everywhere in the county. These contradictions encapsulate how the children of immigrants could have a fragile relationship with their parents’ birthplace as they often experience the country through the lens of others, very rarely their own.

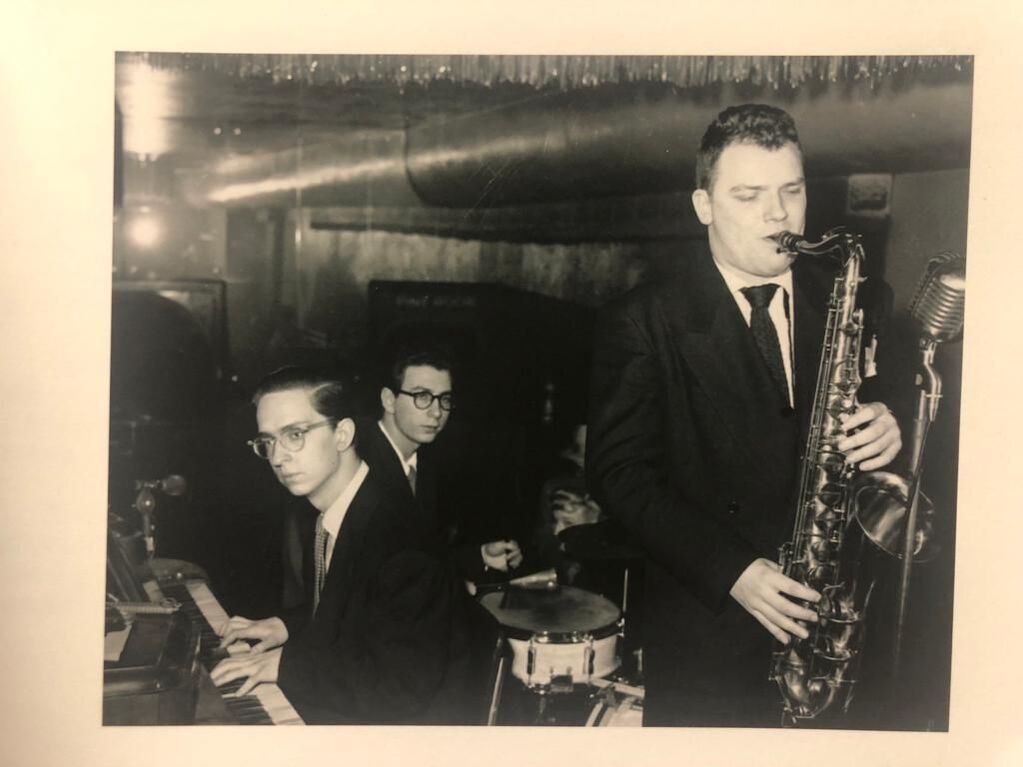

Blog post by Les Back, University of Glasgow, UK

Howard S Becker’s life provides the archetype for the argument developed in my published Identities article, ‘What sociologists learn from music: identity, music-making, and the sociological imagination’. Its completion coincided with the sad news of his death on 16th August 2023 at his home in San Francisco aged 95. In a way, my Identities article is an homage to one of the greatest sociological minds of our time, and a pretty decent piano player too. The study, based on interviews from 29 contemporary sociologists, found that musical life offers sociologists an interpretive device for understanding society or practical form of insight. This is not only confined to the artful sociology at the more humanities end of the disciplinary spectrum, but can be found even amongst scholars who see sociology as a science.

Blog post by Hamdullah Baycar, University of Exeter, UK

‘It kind of makes me feel like Batman or Superman. You can say the things you want to say with your own voice and your own style’, said Malcolm Bidali, a Kenyan security guard employed in Qatar, regarding his activism about labour conditions on social media. His activism led to his detention in 2021. The incident gained significant public attention, and 240 Qatar Foundation students, alums, faculty and staff signed a petition asking for his release.

Two days after the petition, even Qatar's state-owned media, Al Jazeera, was involved in the debate and ran with the headline, ‘Concerns over Qatar's arrest of a Kenyan security guard’. Thus, the digital sphere, which initially caused his detention, ultimately became the tool that freed him. Although Bidali's case cannot be considered representative of the entire Gulf region and is not directly related to the UAE, it does demonstrate the power of social media and the digital sphere, even in supposedly autocratic states.

What does a Thai person look like? How do expectations about citizenship create an ethicized cultural phenotype? In our Identities article, ‘Turbaned northern Thai-ness: selective transnationalism, situational ethnicity and local cultural intimacy among Chiang Mai Punjabis’, we explore family histories, selective transnationalism and regional Lanna identities among Thai citizens with Punjabi heritage and selective cultural identity. This article argues that Punjabi Thais maintain their networks and cultural connections with a historic ancestral homeland, but they also cultivate forms of local cultural intimacy in ways which leapfrog the linguistic and cultural hegemony of Thai national identity. In other words, despite their non-Thai appearance, these Punjabi Thais have deeply local cultural knowledge, speak Northern Thai language fluently and have Northern Thai cultural sensibilities.

In our Identities article, ‘I became a Taiwanese after I left Taiwan’: identity shift among young immigrants in the United States’, we seek to engage with transnationalism literature, which argues that migrants continue to remain concerned with their origin country. As our case study shows, successful assimilation into the host country does not mean migrants will relinquish their previous attachment. In fact, fresh experiences abroad might actually activate and intensify their homeland identity. Our study documents unpleasant contacts with people coming from People’s Republic of China (PRC) and personal experiences with the immigration rules that favour Taiwanese. Our interviewees also share the disenchanting discovery that America was actually lagging behind Taiwan in terms of healthcare, public transportation and recycling, which encourages these young migrants to cherish heir Taiwanese identity. In short, being Taiwanese is something one can take pride of, and therefore, our interviewees explained they do not want to be viewed by people from PRC as their 'compatriots’ or identified as ‘Chinese’ by their American friends.

In 2018, the research department of Awel, a Flemish civil society organization, published a report on the impact of the late terrorist attacks in Europe on the identity formation of minority youth. The report, based on testimonials, revealed that some Muslim children try to hide their ethno-religious background out of fear of being verbally attacked. Some even wish to ‘unbecome’ Moroccan or Muslim to respond to Islamophobia.

The largest ethnic minority group in Belgium originates from Morocco. This primarily Muslim group is indeed strongly stigmatized, even more so since 9/11. It is argued that terrorist attacks increase Islamophobic or anti-Muslim sentiments, which hence also impacts the well-being of Muslim children living in Flanders. The findings of the research report nevertheless did not receive as much public and political attention as deserved. Yet, ethnic minority citizens’ identity formation has long been a subject of political interest, especially since many politicians across the spectrum propose that minorities, and particularly Muslims, do not identify as Belgian.

‘Identity’ is probably amongst the most circulated terms in the academy and beyond. However, a critical reflection on the use of this term in the context of cross-cultural fictional narratives could reveal a major issue. Rather than representing a genuine state of human condition, the term has become a strategic means used by some minority writers to boost readership for their writings.

Given the hierarchies of the world literary system consisting of influential agents such as critics, publishers and marketing expectations, certain languages, regions, styles and poetics are privileged over others. The world literary system thus mirrors the ‘neo-imperial contours of global capitalism’, dominated by multinational publishing conglomerates with powerhouses in London and New York. My Identities article, ‘We have much identity’: contesting the claimed hybrid identity in Faqir’s My Name is Salma and Ahdaf Soueif’s In the Eye of the Sun’, examines how some Arab Anglophone women writers manipulate identity constructions and essentialise their hybrid identities as a strategy to boost readership and market values for their works. Through a close reading of Fadia Faqir’s My Name is Salma and Ahdaf Soueif’s In the Eye of the Sun, the article reverses the gaze on the societies that these texts claim to reveal.

A number of different aspects of identity are relevant to young people, from self-esteem, distinctiveness, self-concept, clarity, coherence and self-continuity. We recently published a paper in the Journal of Social Psychology Research on the importance of the social context as a component self-continuity. Using young adults (ages 19-25) from the US and Brazil, our latest research demonstrates that the social context, specifically our friends and family, is a novel, measurably distinct self-continuity strategy. In particular, the results from our study exemplify that relationships continue to play an important role in healthy identity development.

Emerging adulthood refers to the period of early adulthood between the ages of 18 and 25. Specifically, it’s characterized as an age for exploring different identities, within the contexts of school, work and romantic relationships, to name a few. Due to the changing roles during this period of the lifespan, this is also an age exemplified by instability. Beyond that, emerging adults can feel in-between adolescence and adulthood, that this is a period of their lives to focus on themselves and that the future contains a range of possibilities for them. As such, this makes for a crucial period to study identity development.

The COVID-19 pandemic profoundly transformed people’s lives, identities and practices throughout the world. It had particular effects on the group of international students who usually move frequently between home country and study destination. When the pandemic hit their study destinations in 2020, they had to take immediate action and plan migratory trajectories accordingly.

Chinese international students (CIS) also experienced a nationwide pandemic control policy at home that caused continuous travel constraints on international flights and passengers landing in China. The domestic policy had a profound impact on their migration aspirations – to remain in the study destination or to return home. Simultaneously, students reconfigured their perceptions of homeland. Our research, as detailed in our Identities article, ‘Migration aspirations and polymorphic identifications of the homeland: (Im)mobility trajectories amongst Chinese international students amidst COVID-19’, includes semi-structured interviews with 33 CIS studying in 23 cities of 10 European countries (including the United Kingdom). We aim to understand how students’ identifications of homeland – a cognitive assemblage of emotions, commitments and reflections towards their home country – intersect with their migration aspirations.

On 24 September 2016, the National Museum of African American History and Culture opened on the National Mall in Washington, D.C. to commemorate the contributions and experiences of people of African descent to the United States. Engraved on one of the walls of the museum reads, ‘I, too, sing America’. These four words are quoted from African American poet Langston Hughes’ poem of the same name. Written in 1926, Hughes’ poem reveals the experiences of African Americans during Jim Crow America. As Hughes poetically writes,

'I, too, sing America.

- Langston Hughes, ‘I, too, am America’, from The Collected Poems of Langston Hughes

UNESCO’s Atlas of Endangered Languages recognises over 2,500 endangered languages worldwide. Languages represent not just a form of communication, but also the cultural knowledge of that language. However, in his book Language Death, David Crystal estimates that the world is in danger of losing nearly half of all accumulated knowledge at the current rate of language loss. With language intrinsically tied to culture, many communities that experience a decline in the use of their native language perceive it as a sign that their culture is dying. The result is often that older generations look for ways to maintain, transmit and revitalise use of their language through younger generations.

The internet is intrinsically connected to issues of language and cultural identity. As language is the primary means for spreading cultural information, internet resources in minority languages can empower speakers of these languages by enabling them to display their own way of life and voice their concerns and issues in their mother tongue. In this way, they may revitalise their languages, reinforce cultural symbols and strengthen cultural identities.

‘What are you?’ When posed with this question in highly racialised societies, most people respond by sharing their racial identity. Although racial identity is a personal decision, the choice is often constrained by the recognised racial categories available within the racialised society.

For example, as written into law through the 1950 Population Registration Act – linchpin legislation that helped set in motion South Africa’s Apartheid system by defining race for its population – to be Coloured was to be ‘a person who is not a white person or a native’ Black/African. To be Coloured meant you were neither/nor. We are now a quarter century into post-Apartheid South Africa and the state has undergone a massive sociopolitical transformation that operates under the ideal to be non-racist. Some changes include the repealing of Apartheid laws, including the Population Registration Act. So how has the transition from the white supremacist Apartheid state impacted Coloured racial identities in post-Apartheid South Africa? I explore how racial identities are created and recreated to adapt to state-level racial (re)formation processes in my recently published Identities article, ‘Able to identify with anything’: racial identity choices among ‘Coloureds’ as shaped by the South African racial state’.

The use of identity markers in sport has received considerable attention from scholars in a number of disciplines over a number of decades. This has been looked at in a variety of different sports and includes insightful studies published in Identities such as the works of Paul Campbell and Daniel Burdsey on football and Constancio Arnaldo on boxing.

In our Identities article, ‘Pretty fly for a white guy: The politics of race, nation and difference in professional boxing’, we look at the ways in which race and nation are (re)presented within the coverage of one particular fight. Boxing is a sport that relies heavily on binary divisions. In his book Boxing and Society, the sociologist John Sugden noted how success in the ring could ‘symbolise not only individual achievement, but also racial and national superiority’. For the promotion of many championship bouts the hype around the fight is constructed around binary oppositions. This paper looks at the bout between Joe Calzaghe (a white boxer from Wales) and Bernard Hopkins (a black boxer from the USA) as a case study to explore the representation of identities. In attempting to tease out some of the key themes to emerge in the intersection of race and nation, we tried to understand how identities are portrayed within boxing. This work also highlighted further differences around the understanding of social class and core/periphery relations within a particular sport. 'A radical Islamist terrorist targeted the nightclub (…) in order to execute gay and lesbian citizens, because of their sexual orientation. It’s a strike at the heart and soul of who we are as a nation.'

- Donald Trump

PRR’s LGBT stances The statement from then-Presidential nominee Donald Trump followed the 2016 mass shooting at Pulse, a gay nightclub in Orlando, Florida. Later, in 2020, Trump referred to himself as 'the most pro-gay President in America'. Simultaneously, he appointed overtly anti-LGBT candidates to judicial positions and oversaw various policies legitimizing the exclusion of LGBTQ+ people. Trump’s contradictory attitude towards LGBTQ+ minorities is emblematic of a broader Western trend in populist radical right (PRR) politics: PRR actors often adopt pro-LGBTQ+ stances whilst simultaneously propagating not only heteronormative family values and conservative religious moralities, but actively anti-LGBTQ+ policies.

On the 14th June 2017, a horrific fire swept through Grenfell Tower in west London, killing 72 people and leaving hundreds more homeless and traumatised. For those of us who witnessed the tragedy unfold, either directly or through media coverage, the images of the burning tower beyond the control of the firefighters will stay with us for a lifetime.

Situated within the wealthy borough of Kensington and Chelsea, with a 71% white demographic, the 24-storey tower block was home to mainly social housing tenants of many ethnicities and backgrounds. Much has been written about how social marginalisation had created a hostile and dangerous environment for residents of the tower. In the years preceding the fire, they were treated as expendable against the forces of gentrification, de-regulation and cuts, and their voiced concerns about the loss of green areas and fire safety in Grenfell Tower were repeatedly ignored. In 2019, the Grenfell Tower Inquiry Report determined that the speed with which the fire spread was due to the combustibility of the substandard exterior cladding, an addition made largely to enhance the tower’s appearance to surrounding neighbourhoods.

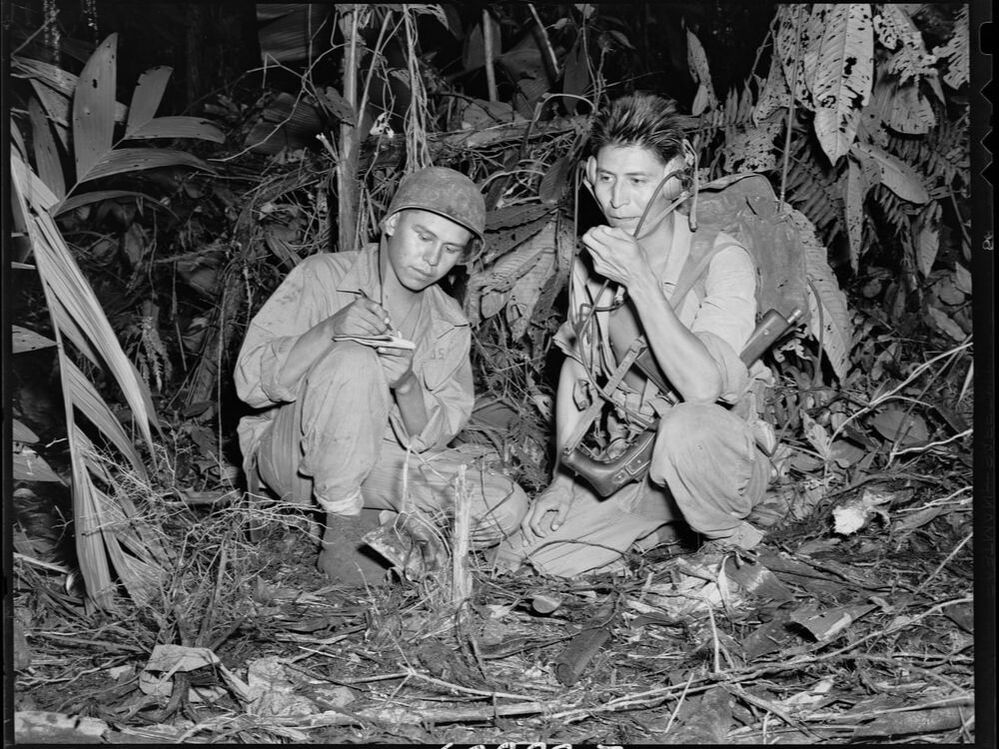

The global Indigenous Rights movement emerged late in the twentieth century, with scholars tracing its origin to postwar international conventions and human rights activism. In my Identities article, ‘World War II and the development of global indigenous identities’, and in a forthcoming book (War at the Margins, University of Hawai’i Press, 2022), I examine how the war created conditions favouring the emergence of Indigenous identity as a form of global political action.

The Second World War mobilised human and natural resources on a massive scale; its aftermath dissolved empires and rearranged the international order. Indigenous men and women — those in small-scale, often tribal, societies at the fringes of national or imperial control — were drawn in as soldiers, scouts, laborers and victims. New Zealand’s Māori Battalion, Navajo codetalkers in the US Marines, Naga guides for the British Army, New Guinean carriers for Allies and Japanese — these and other Indigenous actors shaped the progress, and sometimes the outcome, of campaigns. Even where front lines did not cross Indigenous homelands, civilians suffered violence, displacement, military occupation, economic and social disruption and forced labour. War created a fluid context for change, highlighting the ambiguous legal position of Indigenous people and altering government and public views of them.

In the early 2010s, France repatriated a large number of Roma back to Romania, following a series of highly controversial reforms by Nicholas Sarkozy’s government (BBC, 2010). Campaigners for human rights, free movement, and workers’ rights hotly contested those harsh actions of forced repatriation, which were widely discussed in international media. A Romanian article called ‘Back to the life of Gypsy in Romania’ (Micu, 2010) suggested that most of the transnational worker Roma went back to their homelands in the rural part of southwestern Romania. Taking an insight into this particular Romanian area, our recent study in Identities: Global Studies on Culture and Power explores perceptions of Roma people amongst the non-Roma community and how the Roma people respond to these perceptions today (Creţan, Covaci and Jucu, 2021).

To understand the social position of the Roma community in Romania, it is necessary to take a step back in history. Following the fall of communism, Eastern and Central European passed through a series of massive social and economic transformations. The area we explored in our study is on the border of Romania and Serbia and has traditionally been multicultural and multi-ethnic. However, it is also the site of long-term marginalization for the Roma communities. The shift towards a capitalist economy has exacerbated their ‘othering’, since the new economy offers the Roma few possibilities. Consequently, many joined the new transnational labour force in Europe, working abroad as seasonal labourers (including those targeted by Sarkozy in France). Others chose to leave behind their traditional skills and assimilate into majority society. The loss of guaranteed work which the Roma had under the communist regime has tended to intensify the post-communist direct discrimination against Roma, since they are often stigmatized as unemployed and dependent on public welfare.

In the aftermath of the 2016 attempted coup against the Erdoğan government in Turkey, several hundred Turkish-Dutch citizens took to the streets in the Netherlands. Some protesters harassed a journalist documenting the protests. Prime Minister Mark Rutte responded by telling the demonstrators to ‘piss off to Turkey’. This statement exemplifies how Turkish-Dutch citizens, born and raised in the Netherlands, can be scrutinised and quizzed about their loyalty and the extent of their integration. When they express deviant behaviour or political views in the eyes of the majority, they are considered ‘Turks’ or ‘Muslims’ only, which is not reconcilable with being ‘Dutch’. Politicians often understand Dutchness in a culturalised way, in which progressive ideals such as gender equality, sexual liberty and democracy are considered to be important signifiers of Dutchness. This frame creates a contrast between progressive ‘natives’ and ethnic minority citizens, who are othered as backwards, not sharing these progressive values.

How do Turkish-Dutch Muslim young adults deal with such stigmatisation? This is the question we raise in our Identities article, ‘Claiming the right to belong: de-stigmatisation strategies among Turkish-Dutch Muslims’. Investigating de-stigmatisation strategies by Turkish-Dutch youngsters contributes to understanding processes of belonging, social inequality and ethnic boundary-making. Stigmatised individuals can contest and rephrase their position, bringing about social change and upsetting existing social categories. To explore de-stigmatisation, we interviewed 25 Turkish-Dutch, Muslim young adults and conducted ethnographic observations in two youth groups.

Due to the accessibility of the internet and the ability of online spaces to bring people together, platforms like social media sites and web forums have allowed globally dispersed communities to engage in conversations about identity and belonging. For my Identities article, ‘Connectivity, contestation and cultural production: an analysis of Dominican online identity formation’, I collected and analysed text data from a web forum that I call ‘DRLive’ to show the kinds of identity discourses that happen online. This site caters to all things Dominican Republic, with free and open forum pages where Dominicans and non-Dominicans participate in discussions covering numerous topics. Adding to work on diaspora, migration, and cultural production among Dominicans, I propose forums and other virtual spaces as additional sites where diasporic and non-diasporic Dominicans come together to talk about and challenge evolving interpretations of identity, history and cultural memory.

Cultural memory, which is defined as a collection of commonly shared historical moments and experiences, is passed on and shared over time by members of a nation. In the case of this forum, for example, I find that ‘the contrived historical narratives propagated in the Dominican Republic throughout the 19th and 20th centuries continue to inform how Dominicans in the country and in the diaspora interpret and construct Dominicanidad.’ Work on virtual spaces often seeks to address how migration might affect the maintenance of cultural memory, especially as second- and third-generation immigrant communities emerge far from their homeland.

Arab Americans have been categorised as White on official government forms for several decades, which grossly misrepresents this population. Advocacy groups unsuccessfully fought during both the Obama and Trump administrations to have the ethnicity category expanded in the 2020 Census. The ramifications of this community remaining uncounted include lack of funding for social, education, and health care services and less leverage in political issues. Along with negating the incredible diversity within this group, such categorisation excludes Arab Americans from affirmative action programmes.

The recognition of this ethnic group on government forms would allow for their inclusion in such programmes, which is crucial given the prominence of discrimination in the US. However, the irony lies in how mainstream society tends to change their view depending on current events. When there are no crises involving Arabs around the world, Arab Americans are seen as White. However, when a crisis does occur involving Arabs – as either transgressors or victims (i.e. 9/11, invasion of Iraq) – they will be gazed upon as ‘Other’ and enemies of America. The rise in hate crimes against Arab Americans – and anyone who fit into the public’s notions of what an Arab or Muslim looks like – following the terrorist attacks of 9/11 is a prime example of this phenomenon. Consequently, regardless of being labeled as White, Arab Americans have experienced discrimination similar to other racially visible minority groups. This begs the question: if they are recognised as White, then why are they treated as ‘Other’?

The recent visit by Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi to Bangladesh to attend celebrations marking 50 years since the birth of the country following the Liberation War in 1971 has drawn attention to the difficult task of building a nation on the back of a brutal and bloody civil war. At least four people were killed by police in the Bangladeshi city of Chittagong during a demonstration against Modi’s visit. Protesters from Hefazat-e-Islam Bangladesh, and counter protestors aligned with Bangladesh’s governing Awami League party, represent the central divide in Bangladeshi politics, between those who tie national identity to Islam and those who tie national identity to ethnicity and the Bengali language. This is a divide sometimes understood as one between those who ‘collaborated’ with the Pakistani military and those who participated in the independence struggle. On the Golden Jubilee of Bangladesh’s birth, this divide continues to shape Bangladesh’s political landscape today.

Using the case of the ‘Urdu-speaking minority’ in Bangladesh, my Identities article, ‘Displacement, integration and identity in the postcolonial world’, considered what the experience of minorities displaced during the Liberation War tells us about the Bangladeshi national imagination today. Their own voices, and the narratives of identity and integration in which they are situated, are revealing of the nature and boundaries of the nation state fifty years on from the country’s birth. Although the country remains divided around the role or significance of religion versus culture, and between those who ‘collaborated’ with the Pakistani military and those who participated in the independence struggle, there are older divides at work here too. Some of those who ended up on the wrong side of the Liberation War are accepted into the nation today. Here colonial narratives of ‘population’ versus ‘people-nation’, ‘community’ versus ‘citizen’ structure exclusion not only through narratives of the country’s foundation myth (as commonly assumed) but also through poverty and social space. |

|

Explore Identities at tandfonline.com/GIDE |

|

The views and opinions expressed on The Identities Blog are solely those of the original blog post authors, and not of the journal, Taylor & Francis Group or the University of Glasgow.