|

|

|

The global Indigenous Rights movement emerged late in the twentieth century, with scholars tracing its origin to postwar international conventions and human rights activism. In my Identities article, ‘World War II and the development of global indigenous identities’, and in a forthcoming book (War at the Margins, University of Hawai’i Press, 2022), I examine how the war created conditions favouring the emergence of Indigenous identity as a form of global political action.

The Second World War mobilised human and natural resources on a massive scale; its aftermath dissolved empires and rearranged the international order. Indigenous men and women — those in small-scale, often tribal, societies at the fringes of national or imperial control — were drawn in as soldiers, scouts, laborers and victims. New Zealand’s Māori Battalion, Navajo codetalkers in the US Marines, Naga guides for the British Army, New Guinean carriers for Allies and Japanese — these and other Indigenous actors shaped the progress, and sometimes the outcome, of campaigns. Even where front lines did not cross Indigenous homelands, civilians suffered violence, displacement, military occupation, economic and social disruption and forced labour. War created a fluid context for change, highlighting the ambiguous legal position of Indigenous people and altering government and public views of them.

Before the 1940s these communities had been marginalised in colonial or national political orders. Manpower demands forced governments to clarify their status. Some, like Ainu and Siberian natives, were already included in national armies. But in the US, federal courts had to decide whether Native American men were citizens subject to conscription. In Canada, First Nations peoples volunteered for service but denied the government’s claim that they could be conscripted or sent overseas. French, British and Japanese militaries recruited and conscripted soldiers and labour throughout their overseas colonies, but policies fluctuated as imperial powers fretted over arming and training colonial units.

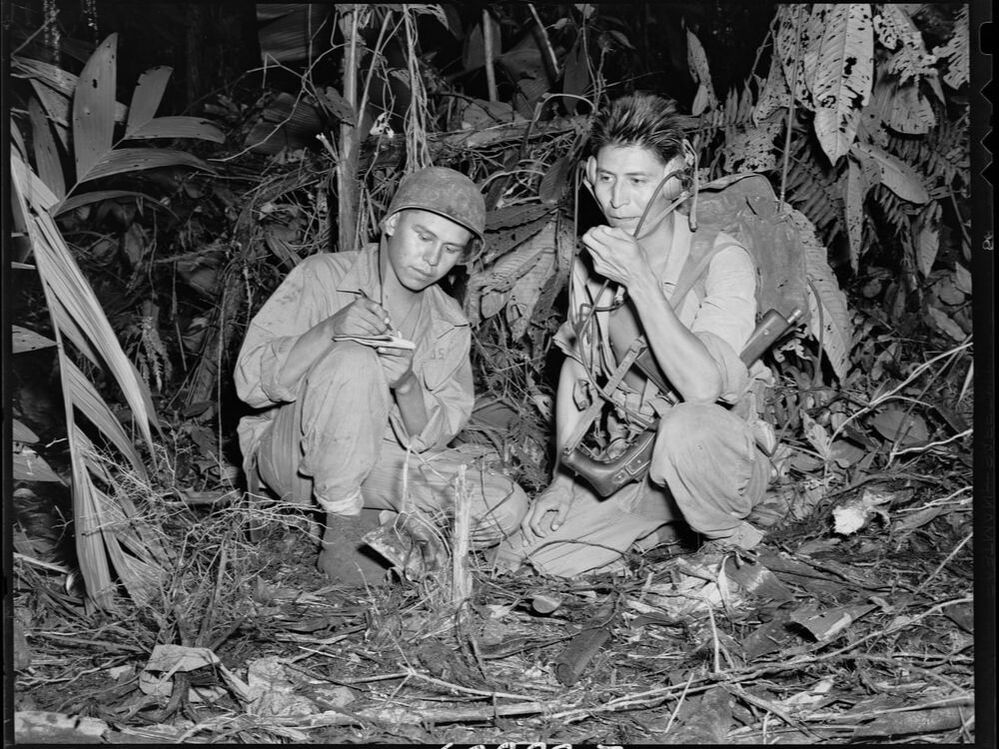

By explicitly asking whether they were citizens and whether men could (or must) serve in the military, official attention focused on these groups in a new way. Indigenous peoples, too, debated questions of loyalty to the nation, their own communities, tradition and treaties. Their service was in part motivated by patriotism, but also by the desire to preserve political independence and cultural distinctiveness. This philosophy was demonstrated vividly when at least six Native American tribes independently declared war against the Axis — asserting their sovereign political statuswhile supporting the national war effort. War highlighted new ways to think about diversity when unique qualities of Indigenous cultures became military assets. A well-publicised example was the Navajo codetalkers, who made their native language into an unbreakable code in the Pacific theatre. More widespread was military use of local knowledge in Indigenous territory. In Norway and Finland, Sámi skills made them valued couriers and guides, as well as effective winter fighters. In the Soviet Army, reindeer herders sledged supplies and the wounded along the Finland front. Australian Aborigines aided reconnaissance along the north coast. In the Burma highlands, Japanese, British and Americans competed for the help of Kachin, Chin, Shan and other locals as guides and soldiers. The war did not generate equality or protection for Indigenous cultures. Indeed, the first postwar decades saw strong assimilationist policies in many places. But war work had increased social and economic integration, and Indigenous leaders used military service to argue for civil rights. Furthermore, the postwar international political order promoted an ideal of political self-determination for minorities and colonial populations; though this originally focused on decolonisation, it offered legal grounding for Indigenous autonomy. The idea that a small community could deal on an equal footing with a nation-state — as when Native Americans declared war on the Axis powers — opened the way for Indigenous peoples to represent themselves as geopolitical actors on the world stage.

Image credit: US National Archives photo no. 593415, Navajo codetalkers Cpl. Henry Bake and Pfc George Kirk on Bougainville, 1943.

Blog post by Lin Poyer, University of Wyoming, Laramie, USA

Read the Identities article: Poyer, Lin. World War II and the development of global indigenous identities. Identities: Global Studies in Culture and Power. DOI: 10.1080/1070289X.2016.1183492

Explore other relevant Identities articles:

Legal indigeneity: knowledge, legal discourse and the construction of indigenous identity in Colombia Indigenous identity, ‘authenticity’ and the structural violence of settler colonialism Indigenous politics: Community formation and indigenous peoples' struggle for self‐determination in northeast India

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

|

Explore Identities at tandfonline.com/GIDE |

|

The views and opinions expressed on The Identities Blog are solely those of the original blog post authors, and not of the journal, Taylor & Francis Group or the University of Glasgow.