|

|

|

Young people in ethnically divided post-conflict societies are often happy to date across ethnic lines, notwithstanding its prevailing discouragement. My recently published Identities article, 'Kiss don't tell: attitudes towards inter-ethnic dating and contact with the Other in Bosnia-Herzegovina', examines this in Bosnia-Herzegovina, which it takes as a typical case of an ethnically divided post-conflict society: young people struggle to meet other ethnic groups due to the high levels of segregation in society. Such contact is also discouraged in the home, in schools, in religious institutions and in the media. I use focus groups conducted on Facebook and follow-up interviews to speak to young people across the country who date across ethnic lines despite these obstacles.

The 550 days of communication blockade that Kashmir witnessed between 5 August 2019 and 5 February 2021 was unprecedented - the longest ever communication blockade in the history of any democracy. Coupled with intimidation, threats and restrictions on movement, the Indian state makes it too difficult for the media to operate freely in the region.

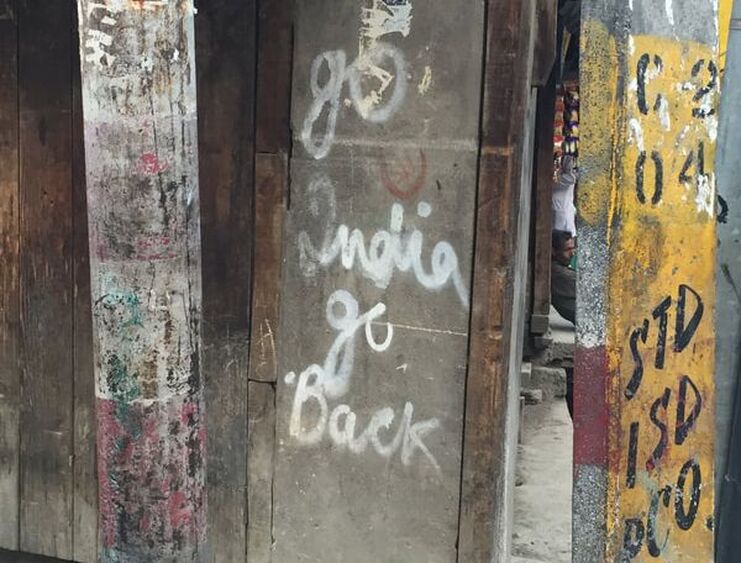

In my Identities article, ‘Communication blackout and media gag: state-sponsored restrictions in conflict-hit region of Jammu and Kashmir’, I highlight the events after the abrogation of Article 370 and its impact on press freedom in the region, especially to understand the perception of local journalists reporting from ground zero post-August 2019. On 5 August 2019, the Narendra Modi led government revoked Article 370 of the Indian constitution that provides quasi-autonomy to the region. In a broader neocolonial context, the abolition of Kashmir's autonomy is also the culmination of the Hindu indigeneity ideology, according to which Muslims on the Indian subcontinent are portrayed as invaders and foreigners, and Kashmiri Muslims are doubly marked as the Other: first as Muslims, and second as Kashmiris committed to an unrelenting struggle for a UN-mandated plebiscite and democratic sovereignty.

The recent visit by Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi to Bangladesh to attend celebrations marking 50 years since the birth of the country following the Liberation War in 1971 has drawn attention to the difficult task of building a nation on the back of a brutal and bloody civil war. At least four people were killed by police in the Bangladeshi city of Chittagong during a demonstration against Modi’s visit. Protesters from Hefazat-e-Islam Bangladesh, and counter protestors aligned with Bangladesh’s governing Awami League party, represent the central divide in Bangladeshi politics, between those who tie national identity to Islam and those who tie national identity to ethnicity and the Bengali language. This is a divide sometimes understood as one between those who ‘collaborated’ with the Pakistani military and those who participated in the independence struggle. On the Golden Jubilee of Bangladesh’s birth, this divide continues to shape Bangladesh’s political landscape today.

Using the case of the ‘Urdu-speaking minority’ in Bangladesh, my Identities article, ‘Displacement, integration and identity in the postcolonial world’, considered what the experience of minorities displaced during the Liberation War tells us about the Bangladeshi national imagination today. Their own voices, and the narratives of identity and integration in which they are situated, are revealing of the nature and boundaries of the nation state fifty years on from the country’s birth. Although the country remains divided around the role or significance of religion versus culture, and between those who ‘collaborated’ with the Pakistani military and those who participated in the independence struggle, there are older divides at work here too. Some of those who ended up on the wrong side of the Liberation War are accepted into the nation today. Here colonial narratives of ‘population’ versus ‘people-nation’, ‘community’ versus ‘citizen’ structure exclusion not only through narratives of the country’s foundation myth (as commonly assumed) but also through poverty and social space.

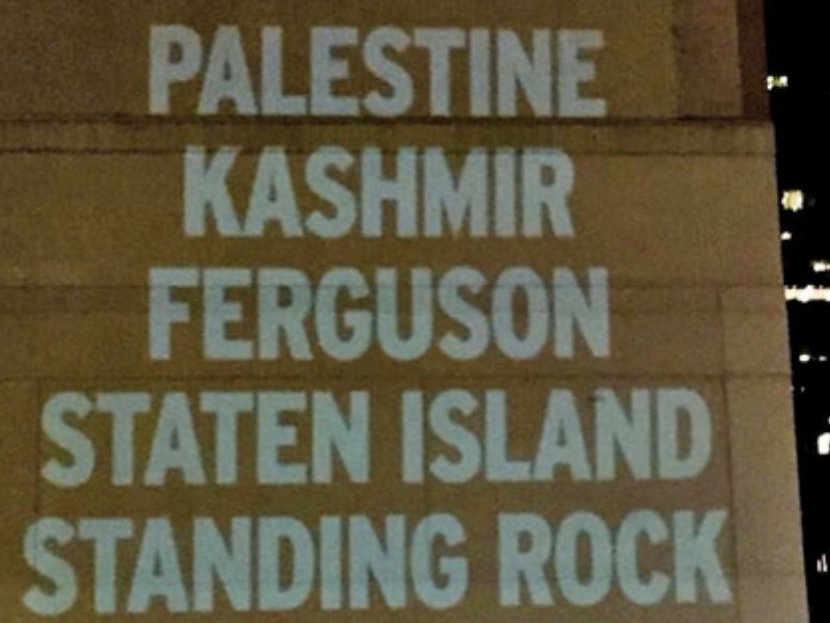

'Kashmir is a Palestine no one talks about'.

I recorded this remark by a friend sympathetic to both struggles almost a decade ago. She knew enough to realise early on as to what was prevalent and what would be unfolding for the Indian occupied Kashmir in the future. As I discuss in my Identities article, ‘"Their wounds are our wounds": a case for affective solidarity between Palestine and Kashmir’, while the political histories of both regions are different, broadly speaking, they ‘seem’ very similar and separated only by continents. Strong overlaps exist in having been midwifed by the waning British Empire in 1947, UN intervention and internationalisation, and in their resistance movements, that are undermined by what the current global politics lumps erroneously as 'Islamic terrorism'. The 'suffering' of people due to the heavy military presence is one of the most visually gripping hallmarks of both struggles. While these overlaps exist, settler colonialism as a fatal project of the Indian occupation of Kashmir has not been very easy to picture, especially for the international community.

'Ayse wasv Dargah Brasvaareye Shabas Asye Mangove Rabas Azadi’ ('We will go to the Hazratbal Shrine on the auspicious Thursday night, we shall pray for our Freedom').

For someone growing up in Kashmir during the time that the 1989 uprising broke out, this song was all too familiar. Witnessing and participating in Azadi rallies in which men, women and children would gather in huge numbers singing and chanting such verses turned the rallies festive. The young generation in 1989 that was moving out for studies in different cities of India saw that in the dominant discourse the 1989 uprising was being portrayed as religious fundamentalism and terrorism. In addition, both scholarly and popular discourse on Kashmir was by and large overshadowed by the Indian and Pakistani national narratives. The regulated access to Indian archives buttressed the official narrative on Kashmir’s past that described the 1989 uprising as an outcome of the grievances that people of the region had vis-à-vis the governance. In this narrative, the aspirations for self-determination and the cyclic collective expressions of right to self-determination in the form of huge Azadi rallies were dubbed as incitation by the Pakistani state.

A key scene in Danis Tanović’s Academy Award-winning film No Man’s Land (2001) features two soldiers, a Bosnian Muslim (a Bosniak) and a Bosnian Serb, who have gotten stuck in a trench during the 1990s Bosnian War. In their joint effort to escape from this unfortunate situation, they draw closer; they talk about their prewar lives and recognise that they have many things in common, even some common acquaintances. However, it comes as no surprise when, in the firestorm of bombshells, the question arises of who is responsible for the destruction of Yugoslavia, of their lives as they were before the murder and devastation. The two soldiers start to swap accusations until the armed Bosniak points his weapon at his opponent and asks one last time: ‘Who started the war?’

Around the world, conflicting parties engage in self-exculpation and self-victimisation – from Bosnia-Herzegovina to Sri Lanka, from Northern Ireland to South Africa, not to mention the Middle East. Denying one’s own responsibility and guilt and the fight over one’s own victim status seems to be a constitutive part of many conflicts and postwar situations. As socio-psychological and sociological research show, self-victimisation is accompanied by several advantages. It not only contributes to a stabilisation of group boundaries by fostering internal cohesion and outward demarcation, but also promotes feelings of moral superiority. Hence, self-victimisation is politically beneficial and a suitable tool for protecting one’s own we-ideal and with it one’s own I-ideal in the context of collective violence. It is the chosen mean to restore those facets of identity, which have potentially been corrupted or injured by the collective violence. But what happens when people are confronted with conflicting perspectives of reality, with perspectives according to which the respective ethnic in-group is not to be considered only as victim of war but also – or even exclusively – as perpetrator?

'Free Kashmir', reads the placard held by a young Indian woman during an anti-Citizenship Amendment Act agitation at the Gateway of India, Mumbai, on 6 January 2020. That India cannot tolerate such 'separtist sentiments' is central to the outrage over the placard. People in her supporting circle defend it on the grounds that it meant freedom from Internet lockdown imposed since 5 August 2019 across Kashmir. The woman comes out with a statement: 'I was voicing my solidarity for the basic constitutional right'.

As Kashmiris, what does it mean to be shown solidarity with terms and conditions, one that disallows a Kashmiri from envisioning their freedom but dictates its meanings and interpretations for them? In our Identities article, 'On Solidarity: Reading Love, Loss, and Longing in Kashmir', we engage with the question of solidarity through a critical reading of Sahba Husain’s book Love, Loss, and Longing in Kashmir. The multiple ways in which claims of solidarity are articulated by Indian ‘progressives’ often result in reflecting dominant narratives that obfuscate the lived realities of the occupied Kashmiri people. This is brought forth in the piece through an analysis of how the concepts of disillusionment, alienation, resilience find expression in these works.

‘And so it begins. India’s settler-colonial project has arrived’, reads the headline of The Medium on the 31st of October 2019. It must be noted that Indian setter-colonialism arrived through a longer colonial engagement, a brutal history of Indian denial of Kashmiri self-determination since October 1947.

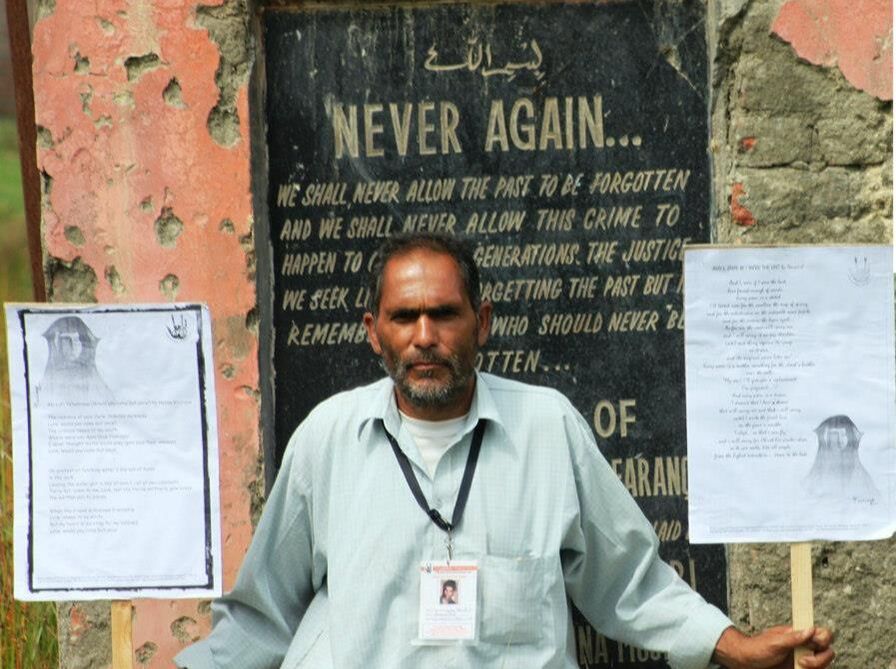

On the 5th of August 2019, the Indian government executed a legally questionable constitutional annexation of the state of Indian-administered Jammu and Kashmir after placing Kashmiris under an unprecedented digital and physical lockdown, a military siege. Kashmir’s semi-autonomous status has long suffered what Duschinski and Ghosh have called a process of occupational constitutionalism. The Jammu and Kashmir Land Reorganisation Act 2019, enacted on the 5th of August, came into effect on the 31st of October 2019. Kashmiris, whose right to determine their political future has been denied for 72 years, will now no longer have the right to exclusive ownership in their land. The Indian government has been busily attracting domestic and foreign investment. A member of the upper house of the Indian Parliament has called for Indian settlers from the armed forces to move into Kashmir. These settler-colonial moves further militarise and destroy an already fragile ecology. Caged physically and digitally, Kashmiris face a demographic change. The Indian state’s record of widespread extrajudicial killings, torture, sexual assault, enforced disappearances and mass graves over the last 30 years has been referenced by the Office of the United Nations’ High Commissioner reports of 2018 and 2019. The militarisation and the threat of demographic change have prompted the US-based Genocide Watch to issue a genocide alert for Kashmir.

The 20th century has witnessed many ethnic and religious conflicts, civil wars, massacres and humanitarian crises all over the world from Southeast Europe to Sudan, and from Rwanda to Northern Ireland. Although negative peace [1] is achieved by signed peace agreements or newly-drawn borders in many cases, this does not necessarily bring about reconciliation and harmonious relations between societies. The violent acts of 1915 -- one of the most catastrophic events in the early 20th century -- deeply damaged Turkish–Armenian relations and still has been affecting new generations. Although some peaceful steps have been taken on a diplomatic level to normalise relations, the intractability of the conflict remains.

Past theory on competitive victimhood demonstrates that contested narratives over being ‘the main victim’ of a conflict are significant obstacles in processes of reconciliation. When victimhood becomes a component of a broader collective identity, it can increase the perception of social prejudice, distrust and hatred towards out-groups. Competitive victimhood refers to a situation in which each side in a conflict claims to be the main victim or legitimise its own crimes on the basis of past victimhood (Noor et al. 2008). Moreover, while in-group crimes are downplayed by moral excuses in such situations, out-group crimes are exaggerated by demonising the enemy (Andrighetto et al. 2012). This leads to competition over who has suffered more and who has more right to resort to violence. Although all members of a community have not experienced violence and harm, victimisation becomes a component of collective identity and gets passed down to subsequent generations. |

|

Explore Identities at tandfonline.com/GIDE |

|

The views and opinions expressed on The Identities Blog are solely those of the original blog post authors, and not of the journal, Taylor & Francis Group or the University of Glasgow.