|

|

|

‘Hong Konger is not a race; it’s a spirit’, claimed a group of ethnic minority advocates of protests against the now-shelved extradition bill and anti-mask law in Hong Kong. The dissociation of Hong Kong identity from race marks the blurring of cultural boundaries between those who are racially Chinese and those who are not. Hong Kong’s political climate appears to play a prominent role in forging a collective identity.

Such an identity claim reflects ethnic minorities’ fulfilled desire to be recognised as Hong Konger like the rest of local Chinese people. My co-authored Identities article with Sivanes Phillipson, 'Bordering on sociocultural boundaries and diversity: negotiating Filipino identities in a Hong Kong multi-ethnic school', presents a relevant scenario in an education setting that speaks to the identity tensions amongst minority groups.

0 Comments

If we are to assume the Shakespearean platitude that 'the eyes are the windows of the soul', then it is not beyond our comprehension that visual images used by NGOs (non-governmental organisations) in their advertisements are carefully curated ideas over who or what is ‘seen’, and more importantly ‘how’ it is seen, and for whom. In today’s progressively changing and competitive media and communications environment, humanitarianism is now a profitable enterprise in our visual-as-currency economy.

On our television screens, in our social media applications and unsolicited pop-up email advertisements, and even among the rumpled pile of outdated magazines in the doctor’s waiting room, the public faces of the international aid and relief industry are seldom out of sight. Whether it is malnourished pot-bellied toddlers wearing western football memorabilia of seasons past, a despondent refugee mother in a displacement camp, or a vast horde of shaven-headed, undifferentiated Black and Brown masses in conflict zones, these images are the aesthetic currencies of commercialised suffering employed by humanitarian organisations to brand themselves and their strategic ambitions, and imbue western audiences with a philanthropic disposition. Visual representations are central to – and orbit around – the phenomenon and work of humanitarianism. When we think of humanitarian work, we often visualise much of the non-western, Black and Brown world. As image producers and disseminators, these organisations set the visual tone within which certain people and places are defined and comprehended – indeed, who (and what) they ‘are’, ‘aren’t’ and ‘ought to be’.

Henri Lefebvre and C.L.R. James were quintessential twentieth-century intellectuals. They were born within six months of each other in 1901. Both lived to within sight of the century’s end: James died in 1989 and Lefebvre in 1991. And, as I argue in my Identities article, 'Passing through difference: C.L.R. James and Henry Lefebvre', their grappling with the times in which they lived led them to articulate a comparable politics.

What kind of politics? One which valued human flourishing more than formal equality. One which considered creative freedom more significant than technological progress. And one which found hope in the way in which ordinary people fought against constraint in their day-to-day lives.

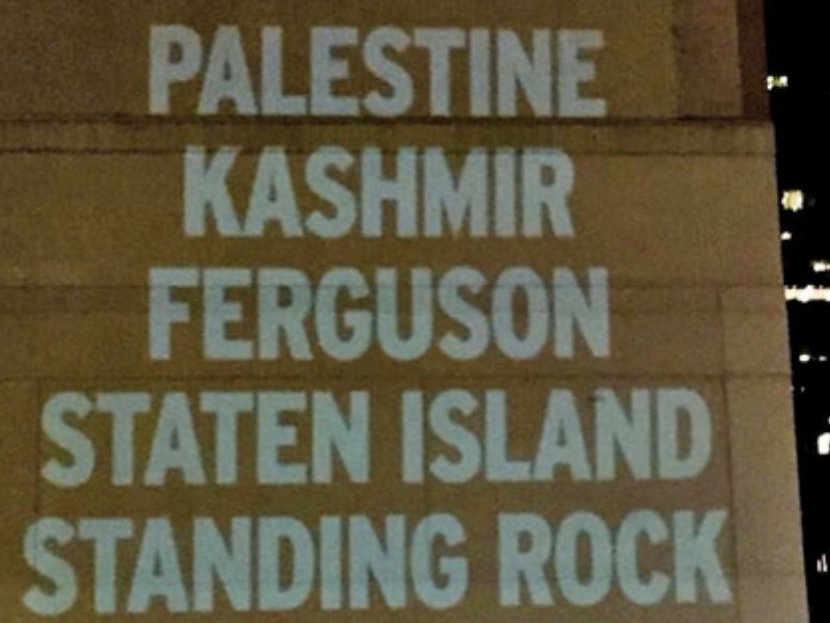

‘And so it begins. India’s settler-colonial project has arrived’, reads the headline of The Medium on the 31st of October 2019. It must be noted that Indian setter-colonialism arrived through a longer colonial engagement, a brutal history of Indian denial of Kashmiri self-determination since October 1947.

On the 5th of August 2019, the Indian government executed a legally questionable constitutional annexation of the state of Indian-administered Jammu and Kashmir after placing Kashmiris under an unprecedented digital and physical lockdown, a military siege. Kashmir’s semi-autonomous status has long suffered what Duschinski and Ghosh have called a process of occupational constitutionalism. The Jammu and Kashmir Land Reorganisation Act 2019, enacted on the 5th of August, came into effect on the 31st of October 2019. Kashmiris, whose right to determine their political future has been denied for 72 years, will now no longer have the right to exclusive ownership in their land. The Indian government has been busily attracting domestic and foreign investment. A member of the upper house of the Indian Parliament has called for Indian settlers from the armed forces to move into Kashmir. These settler-colonial moves further militarise and destroy an already fragile ecology. Caged physically and digitally, Kashmiris face a demographic change. The Indian state’s record of widespread extrajudicial killings, torture, sexual assault, enforced disappearances and mass graves over the last 30 years has been referenced by the Office of the United Nations’ High Commissioner reports of 2018 and 2019. The militarisation and the threat of demographic change have prompted the US-based Genocide Watch to issue a genocide alert for Kashmir.

The 20th century has witnessed many ethnic and religious conflicts, civil wars, massacres and humanitarian crises all over the world from Southeast Europe to Sudan, and from Rwanda to Northern Ireland. Although negative peace [1] is achieved by signed peace agreements or newly-drawn borders in many cases, this does not necessarily bring about reconciliation and harmonious relations between societies. The violent acts of 1915 -- one of the most catastrophic events in the early 20th century -- deeply damaged Turkish–Armenian relations and still has been affecting new generations. Although some peaceful steps have been taken on a diplomatic level to normalise relations, the intractability of the conflict remains.

Past theory on competitive victimhood demonstrates that contested narratives over being ‘the main victim’ of a conflict are significant obstacles in processes of reconciliation. When victimhood becomes a component of a broader collective identity, it can increase the perception of social prejudice, distrust and hatred towards out-groups. Competitive victimhood refers to a situation in which each side in a conflict claims to be the main victim or legitimise its own crimes on the basis of past victimhood (Noor et al. 2008). Moreover, while in-group crimes are downplayed by moral excuses in such situations, out-group crimes are exaggerated by demonising the enemy (Andrighetto et al. 2012). This leads to competition over who has suffered more and who has more right to resort to violence. Although all members of a community have not experienced violence and harm, victimisation becomes a component of collective identity and gets passed down to subsequent generations. |

|

Explore Identities at tandfonline.com/GIDE |

|

The views and opinions expressed on The Identities Blog are solely those of the original blog post authors, and not of the journal, Taylor & Francis Group or the University of Glasgow.