|

|

|

'Kashmir is a Palestine no one talks about'.

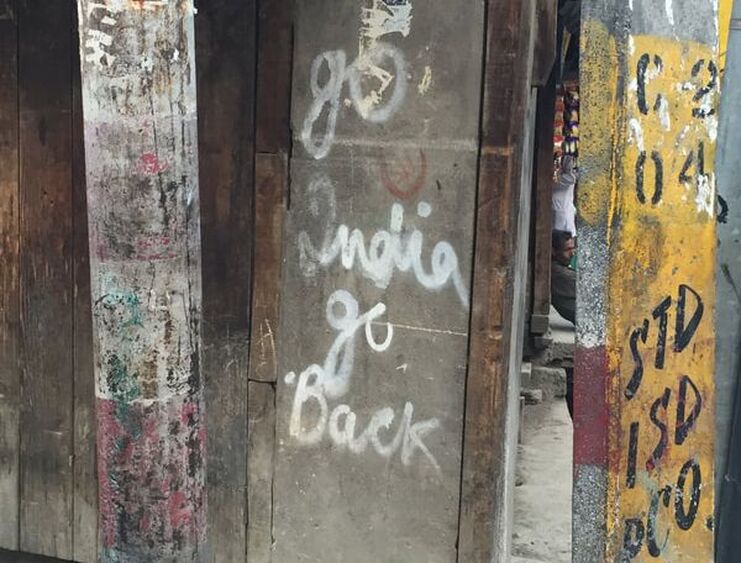

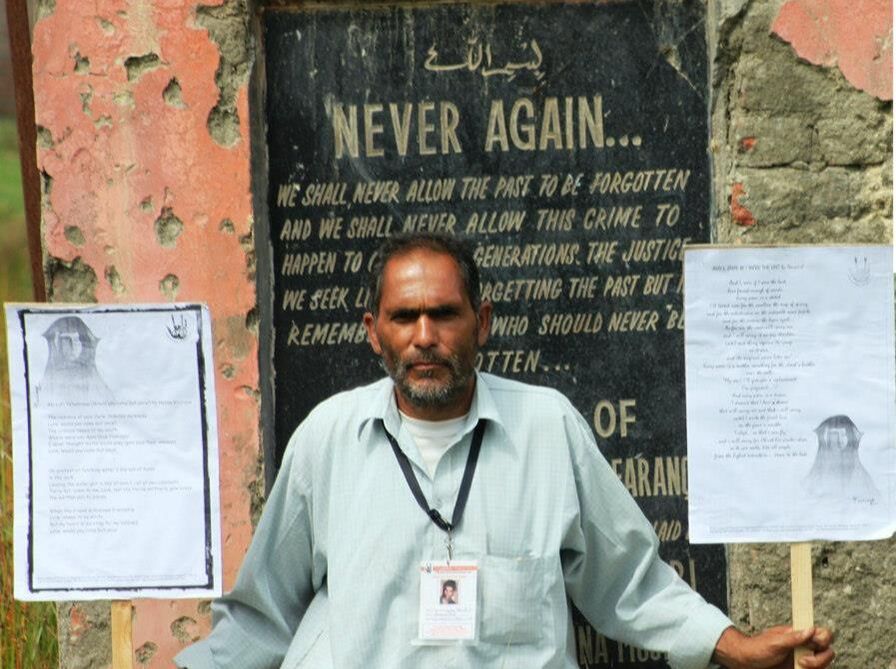

I recorded this remark by a friend sympathetic to both struggles almost a decade ago. She knew enough to realise early on as to what was prevalent and what would be unfolding for the Indian occupied Kashmir in the future. As I discuss in my Identities article, ‘"Their wounds are our wounds": a case for affective solidarity between Palestine and Kashmir’, while the political histories of both regions are different, broadly speaking, they ‘seem’ very similar and separated only by continents. Strong overlaps exist in having been midwifed by the waning British Empire in 1947, UN intervention and internationalisation, and in their resistance movements, that are undermined by what the current global politics lumps erroneously as 'Islamic terrorism'. The 'suffering' of people due to the heavy military presence is one of the most visually gripping hallmarks of both struggles. While these overlaps exist, settler colonialism as a fatal project of the Indian occupation of Kashmir has not been very easy to picture, especially for the international community.

0 Comments

In the 1950s, the world famous American-born entertainer Josephine Baker, who lived in France, toured the US. She was refused in 36 hotels in New York because she was black.

Back in France, Baker adopted twelve children from 10 different countries in order to prove to the world that people of all ‘races’ and religions could live together. She organised tours through the castle where she lived with her ‘rainbow tribe’ and made the children sing and dance. In the 1920s and 1930s the popular novelist Pearl S. Buck adopted seven children, four of whom were labelled ‘mixed-race’. By doing so she flaunted American restrictions on mixed-race adoptions. In the 1950s, Buck said she did so because she wanted to show that families formed by love – devoid of prejudices based on race, religion, nation, and blood – were expressions of democracy that could counteract communist charges that America’s global defence of freedom was deeply hypocritical. The adoptions by Baker and Buck were political statements that illustrate that intercountry adoptions were frequently about much more than saving a child, as many people who defended adoptions claim. My Identities article, ‘Parenting, citizenship and belonging in Dutch adoption debates 1900-1995’, explains why debates on this issue continued, without ever reaching a conclusion. Celebrities (including Madonna, Angelina Jolie and Brad Pitt) followed in the footsteps of Baker and Buck. Non-celebrities copied behaviour and arguments. Adopters tried to show that children and adults not connected by blood ties could form a family, and that single parent adoptions or adoption by same sex couples could work. Critics pointed to child kidnappings, trafficking, ‘baby farms’ and a profit-driven industry based on global inequality. Adoption was not a solution to poverty, nor in the best interest of the child, in their view.

'Ayse wasv Dargah Brasvaareye Shabas Asye Mangove Rabas Azadi’ ('We will go to the Hazratbal Shrine on the auspicious Thursday night, we shall pray for our Freedom').

For someone growing up in Kashmir during the time that the 1989 uprising broke out, this song was all too familiar. Witnessing and participating in Azadi rallies in which men, women and children would gather in huge numbers singing and chanting such verses turned the rallies festive. The young generation in 1989 that was moving out for studies in different cities of India saw that in the dominant discourse the 1989 uprising was being portrayed as religious fundamentalism and terrorism. In addition, both scholarly and popular discourse on Kashmir was by and large overshadowed by the Indian and Pakistani national narratives. The regulated access to Indian archives buttressed the official narrative on Kashmir’s past that described the 1989 uprising as an outcome of the grievances that people of the region had vis-à-vis the governance. In this narrative, the aspirations for self-determination and the cyclic collective expressions of right to self-determination in the form of huge Azadi rallies were dubbed as incitation by the Pakistani state.

Othering processes are inherently complex, and in forced migration contexts, national public discourses tend to reverberate with anxieties over antagonism, discrimination and increasing tensions.

As an alternative to this public discourse, which ultimately tends to associate migrants and refugees with social threat, we might examine pockets of private and semi-private spaces from which quieter voices – women’s voices, perhaps – could catalyse more positive attitudes and better informed perceptions with a gender lens. One space where such voices might emerge is in all-women ‘gün’ (or ‘day’) groups. These are periodic, informal gatherings of relatives, friends and/or acquaintances, usually hosted in one member’s home, and are crucial spaces for women’s interaction and socialisation in Turkey. In fact, in my Identities article, co-authored with Hatice Mete, ‘The afraid create the fear: perceptions of refugees by “gün” groups in Turkey’, we analysed conversations from several of these groups in Mersin in order to investigate local women’s perceptions of forcibly displaced Syrians. |

|

Explore Identities at tandfonline.com/GIDE |

|

The views and opinions expressed on The Identities Blog are solely those of the original blog post authors, and not of the journal, Taylor & Francis Group or the University of Glasgow.