|

|

|

'Ayse wasv Dargah Brasvaareye Shabas Asye Mangove Rabas Azadi’ ('We will go to the Hazratbal Shrine on the auspicious Thursday night, we shall pray for our Freedom').

For someone growing up in Kashmir during the time that the 1989 uprising broke out, this song was all too familiar. Witnessing and participating in Azadi rallies in which men, women and children would gather in huge numbers singing and chanting such verses turned the rallies festive. The young generation in 1989 that was moving out for studies in different cities of India saw that in the dominant discourse the 1989 uprising was being portrayed as religious fundamentalism and terrorism. In addition, both scholarly and popular discourse on Kashmir was by and large overshadowed by the Indian and Pakistani national narratives. The regulated access to Indian archives buttressed the official narrative on Kashmir’s past that described the 1989 uprising as an outcome of the grievances that people of the region had vis-à-vis the governance. In this narrative, the aspirations for self-determination and the cyclic collective expressions of right to self-determination in the form of huge Azadi rallies were dubbed as incitation by the Pakistani state.

Like many young Kashmiris from my generation, while growing up in the region during this period I attempted to answer the question as to why and how the whole of Kashmir was out on the streets in 1989 participating in huge Azadi marches. For my research participants, I was a fellow Kashmiri to whom they could entrust the privileged role of keeper and conveyor of their stories. In my Identities article, ‘Doing research in a ‘conflict zone’: history writing and archival (im) possibilities in Jammu and Kashmir’, by drawing from my ethnographic field work in the region, I describe how embodied stories of Kashmiris punctuate the past often silenced by dominant Indian narratives.

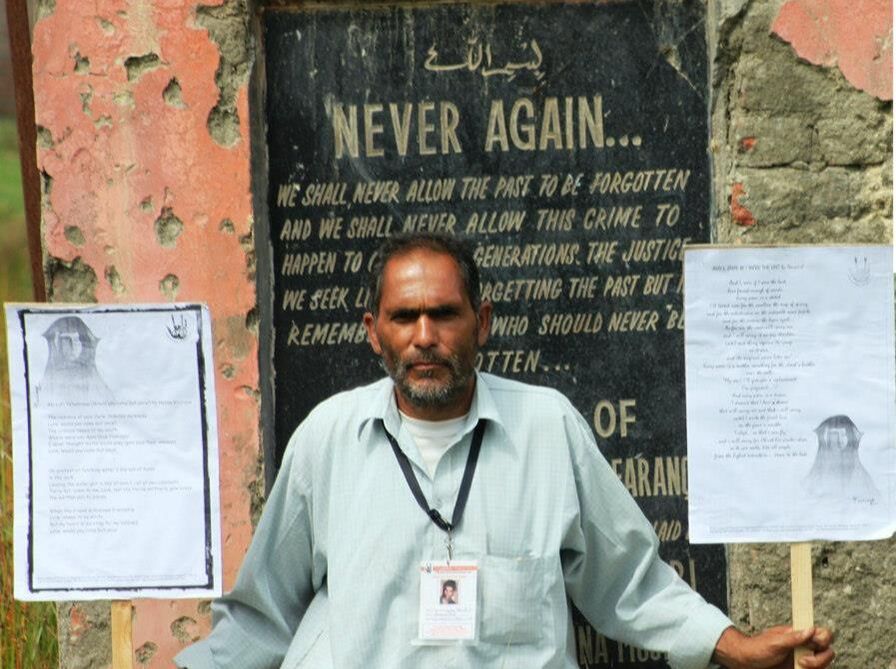

In the article, I also highlight how presence or absence of documents in official repositories informs the present and future politics in the region. I argue that there is a politics to the restrictions on access to materials in official repositories, and such restrictions reflect the effects of power. I describe how Kashmiri narratives about certain key political events in the region’s past co-exist with other forms of memory. I also describe how the embodied experience of the Kashmiri people belies the official Indian narrative about Kashmir’s past. The people of the region weave these stories, building an archive based on their lived experiences. Such archives are often informal and fragmented and reflect the precarious contexts in which they are produced. They also reflect the commitment, passion and desire of the communities to document and record their own histories. For my research on the 1989 uprising, I accessed a diversity of material that included novels, anecdotes and underground literature written by different political activists who were affiliated with the uprising. I argue that such material is a part of an embodied archive and is a rich resource for recovering stories silenced by the official archives.

Blog post by Farrukh Faheem, Institute of Kashmir Studies, University of Kashmir, India

Read the full article: Faheem, Farrukh. Doing research in a ‘conflict zone’: history writing and archival (im) possibilities in Jammu and Kashmir. Identities: Global Studies in Culture and Power. DOI: 10.1080/1070289X.2020.1738099

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

|

Explore Identities at tandfonline.com/GIDE |

|

The views and opinions expressed on The Identities Blog are solely those of the original blog post authors, and not of the journal, Taylor & Francis Group or the University of Glasgow.