|

|

|

Blog post by Ashlee Christoffersen, Aerin Lai and Nasar Meer, University of Edinburgh, UK

RACE.ED and Identities: Global Studies in Culture and Power have published a new collection of essays exploring racial justice work in higher education, titled Advancing Racial Equality in Higher Education. The collection follows on from the event “Racial Equity Work in the University and Beyond: The Race Equality Charter in Context”, which explored what racial equality means in higher education and was organized following publication of the report of a large-scale review of the Race Equality Charter. Advance HE’s Race Equality Charter (REC) is a UK wide programme that began in 2016 aiming to improve the representation, progression and success of Black, Asian and minority ethnic staff and students[i] within higher education. REC is one tool for addressing racial injustice in higher education institutions.

0 Comments

Where can Others turn? On (de)coloniality, messy refusals and alternatives to Eurocentric modernity19/7/2023

Blog post by Ali Kassem, National University of Singapore

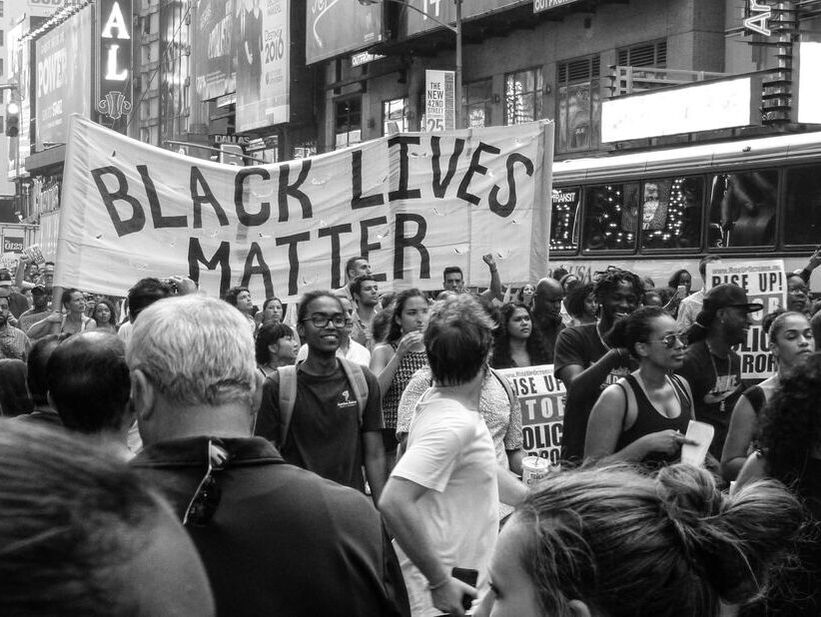

Over the past years, decolonization has emerged as a key project, discourse, and buzzword across academic and public debates. Within this has been a growing recognition of the nature of Eurocentric hegemony, ongoing global connected coloniality and various pressing global crises. A growing movement to contest Eurocentric modernity and its narratives across scales: from anti-racism to ecological resistance has consequently grown and been increasingly hollowed, demonized and attacked. In researching forms of inequalities and racisms in Lebanon, focusing on the country’s Muslim communities, my research has identified a significant anti-Muslim racism pervading the lives of Lebanese Muslims. Deeply structured by and entangled with Eurocentric/modernity coloniality and articulated at the intersection of the (historical and contemporary) local and global, this anti-Muslim racism emerges as a key axis of coloniality’s assault, erasure and violence at the level of everyday lived experiences. Bringing to fore the presence and prevalence of anti-Muslim racism within the Arab-majority world, the eastern Mediterranean and Muslim communities themselves, my work has offered a series of contributions in rethinking the so-called Middle East, racism and Islamophobia studies, as well as the global workings of coloniality beyond the Atlantic.

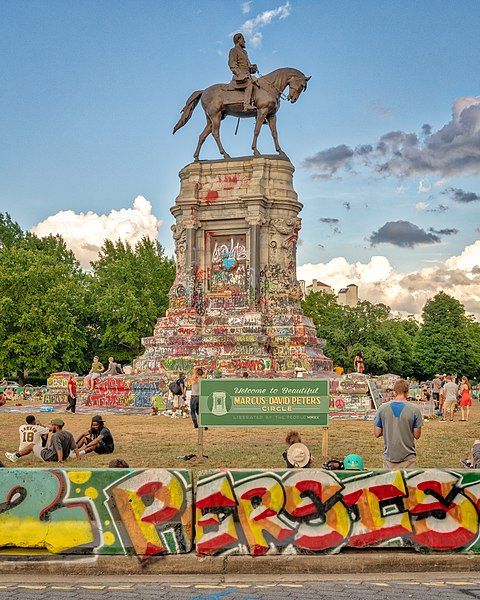

On 8th September 2021, a crowd gathered on Monument Avenue in Richmond, Virginia, USA, near the base of its iconic statue of Confederate General Robert E. Lee. The atmosphere in the crowd was jubilant as workers positioned a crane, wrapped the statue in a harness, and finally–after an hour of preparation, a year of court cases, and 131 years of racial terror set in stone–pulled the statue down from its plinth.

The equestrian statue of Robert E. Lee, Commander of the Confederate Army, is, and always has been, a symbol of white supremacy. Its removal creates the opportunity to change the meaning of the space it once occupied. For the past year at the Centre on the Dynamics of Ethnicity (University of Manchester), we have interviewed activists, policymakers, and cultural workers involved in contesting fourteen statues of slavers and colonisers in five countries. We have also explored the meanings of statues of empire and colonialism with young people from Manchester Museum’s OSCH Collective who shared how statues of white supremacy in towns and cities they call home impacted their sense of belonging. Our research highlights how anti-racist activists draw from global movements to contest local histories and memories. Equally, we consider how strategies for removing Confederate statues in the US (for example) might provide lessons for challenging imperial statues in the UK.

Coloniality deserves special attention to contextualise Professor Hempton’s lecture on “Women’s Networks: Opportunities and Limitations”. First, the context that overlaps historical and political elements: the year 1888. The poster at the back of Professor Hempton as he delivered the talk informed that the Gifford Lecture series dates from 1888. In the same year, Brazil declared the Abolition of Slavery – the last country in the Americas to officialise such law that is not fully put into practice as many cases of forced labour and slavery remain current.

That reminded me of so many unofficial Black women’s collectives who organised as a quilombo, favelas communities, marginalised neighbourhoods (periferias) as they created ways to resist and refuse the places that the colonial-hegemonic society imposed on them. For example, the Herstories of Dandara and Luiza Mahin. Dandara refused to be enslaved and became a quilombo leader, a warrior, agriculture worker in the initial land rights, abolitionists, antiracist and feminist movements in Brazil during the late 1600s. Luiza Mahin was a Muslim, enslaved domestic worker, strategist of one of the most remarkable pro-abolitionist revolutions in Brasil – the Malês Revolt – organised by enslaved peoples. Her Islamic, Jêje-Nago and Yoruba backgrounds are the marks of intersecting systems of beliefs that to this day are erased in the narrative about Brazil’s national identity.

Cross-posted from British Sociological Association

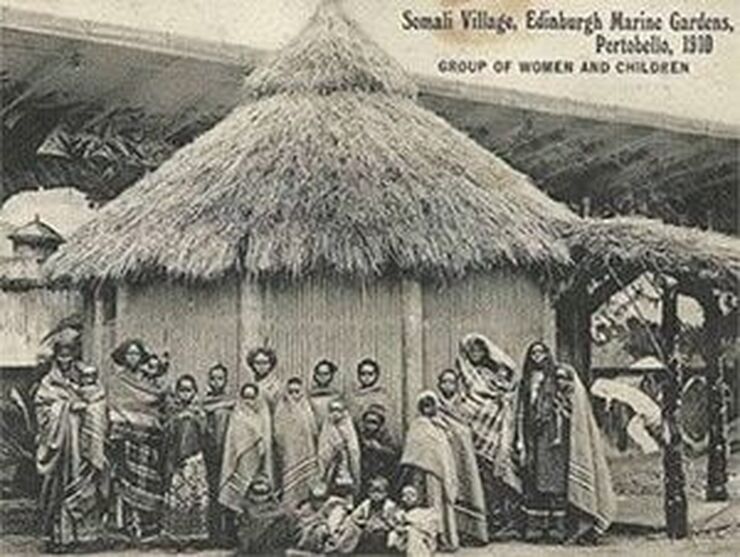

How is history written and by whom? These are questions that have been raised with frequency across the decolonising movement and in particular, by the Cadaan Studies movement, which has focused on knowledge production relating to Somali people. Started in 2015 by Harvard doctoral candidate, Safia Aidid, the movement provides a framework through which to critique the role of whiteness and white privilege in shaping narratives about Somali people. The canonical work of Glaswegian-born I.M. Lewis has come under particular scrutiny not in the least due to his twin roles as anthropologist and administrator for the British colonialists in (then) British Somaliland in the 1950s. Yet whilst the colonialist activities of a Scotsman in Somalia shaped global discourses about Somali people, the narratives of Somali people in contemporary Scotland, many of whom now live in the same area of Glasgow in which Lewis was born, remain absent from local and transnational histories. We unravel and critique this absence. Today in Scotland, there is a Somali population of up to 4000 people. The population has grown in the main since 1999, following the state-enforced dispersal of asylum seekers to sites around the UK. Despite residing in Scotland for nearly two decades, the Somali population continues to be framed in these terms, considered ‘new’, as ‘migrant’; as without history prior to arrival in Scotland and without historical links to Scotland. These narratives obscure a much longer history of Somali people living in Scotland, and of Scotland’s relationship with Somalia.

In the late 1970s, Hasan Khater was the first inhabitant of the Jawlan (Golan Heights), a Syrian land occupied by Israel since 1967, to cross the militarised border and travel to Damascus to study fine arts. Despite his ambition to become a sculptor, Khater was forced to train as a painter, as Israeli security restrictions did not permit him to cross the border with hard materials. Today, despite the ongoing occupation, Khater’s sculptures couch main squares and public spaces in the remaining Syrian villages of the Jawlān, commemorating five decades of relentless political resistance of the native population.

The Jawlan today is home to around 20,000 people, most of them Druze by religion, who live on a land that is dominated by almost equal number of Jewish-Israeli settlers. However, not long ago, this land and its Druze inhabitants were simply Syrian. They were part of a larger Syrian Jawlani community that counted more than 150,000 people of diverse religious and ethnic backgrounds, including Sunnis, Kurds, Armenians and Alawites, among others. Soon after the Israeli occupation, the Jawlan transformed into a borderland; it was cut off from its Syrian continuity, and re-oriented to face Israel. The Jawlani community offers an important perspective on anticolonial world-making, particularly because of its stubborn refusal of colonial integration and its rejection of repeated impositions of Israeli citizenship. However, refusal is not enough to reconstruct a creative sense of liberated being. For this to happen, self-realisation of a capable independent existence is essential to disengagement from colonial mental violence. Many local artists in the Jawlan have been the main social force in creatively imagining new horizons of freedom. This research project began in the summer of 2018, as an attempt to examine not simply how art reflects reality, but how it transforms it.

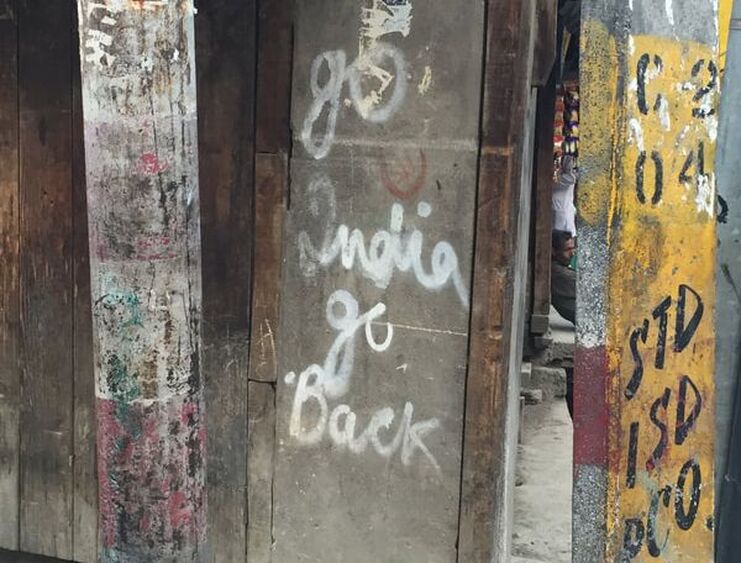

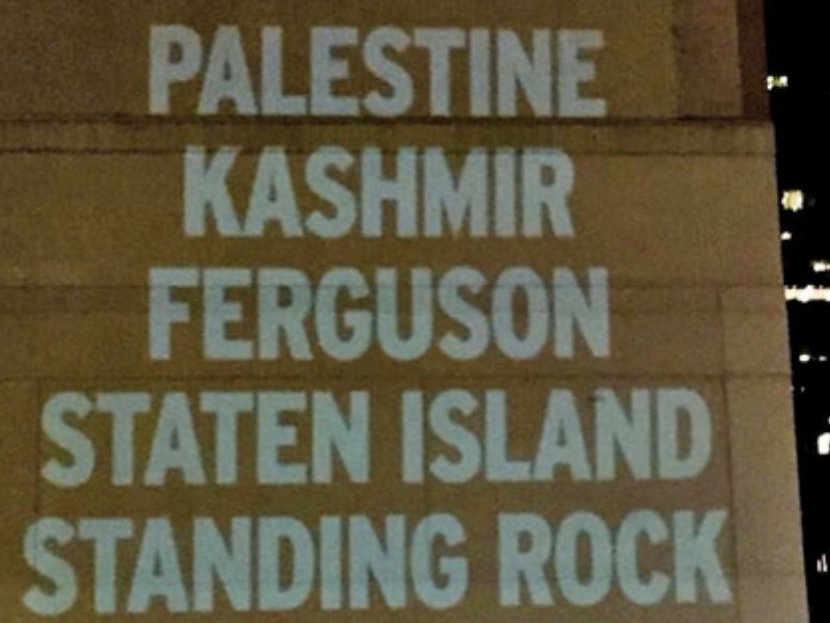

'Kashmir is a Palestine no one talks about'.

I recorded this remark by a friend sympathetic to both struggles almost a decade ago. She knew enough to realise early on as to what was prevalent and what would be unfolding for the Indian occupied Kashmir in the future. As I discuss in my Identities article, ‘"Their wounds are our wounds": a case for affective solidarity between Palestine and Kashmir’, while the political histories of both regions are different, broadly speaking, they ‘seem’ very similar and separated only by continents. Strong overlaps exist in having been midwifed by the waning British Empire in 1947, UN intervention and internationalisation, and in their resistance movements, that are undermined by what the current global politics lumps erroneously as 'Islamic terrorism'. The 'suffering' of people due to the heavy military presence is one of the most visually gripping hallmarks of both struggles. While these overlaps exist, settler colonialism as a fatal project of the Indian occupation of Kashmir has not been very easy to picture, especially for the international community.

'Free Kashmir', reads the placard held by a young Indian woman during an anti-Citizenship Amendment Act agitation at the Gateway of India, Mumbai, on 6 January 2020. That India cannot tolerate such 'separtist sentiments' is central to the outrage over the placard. People in her supporting circle defend it on the grounds that it meant freedom from Internet lockdown imposed since 5 August 2019 across Kashmir. The woman comes out with a statement: 'I was voicing my solidarity for the basic constitutional right'.

As Kashmiris, what does it mean to be shown solidarity with terms and conditions, one that disallows a Kashmiri from envisioning their freedom but dictates its meanings and interpretations for them? In our Identities article, 'On Solidarity: Reading Love, Loss, and Longing in Kashmir', we engage with the question of solidarity through a critical reading of Sahba Husain’s book Love, Loss, and Longing in Kashmir. The multiple ways in which claims of solidarity are articulated by Indian ‘progressives’ often result in reflecting dominant narratives that obfuscate the lived realities of the occupied Kashmiri people. This is brought forth in the piece through an analysis of how the concepts of disillusionment, alienation, resilience find expression in these works.

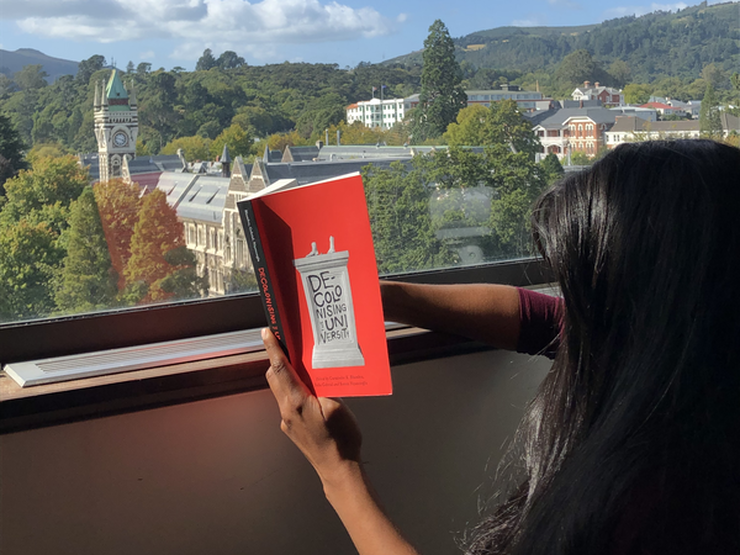

Recent calls to decolonise the university in South Africa culminated in the removal of the statue of Cecil John Rhodes at the University of Cape Town and breathed new life into student-led campaigns around the world to rethink the curriculum. Challenging the colonial roots and Western biases of universities is, of course, not a twenty-first century phenomenon. However, in its latest iteration, the need to decolonise the university has been more clearly connected to the lived reality of the corporatised university as a distinct feature of the neoliberal era. Bringing debates on neoliberalism into closer conversation with a consideration of how neocolonialism is expressed in institutions of higher education has allowed for closer scrutiny of what ‘transformation’ actually means.

It has become abundantly clear to many of those who work and study in higher education, that the more things change, the more they stay the same. While the language of transformation has been woven into policies that have widened access to previously marginalised groups (including black and minority ethnic groups, women, indigenous and mature students), institutions of higher learning have a long way to go to dismantle the barriers to success that these groups face once inside the institutions.

Henri Lefebvre and C.L.R. James were quintessential twentieth-century intellectuals. They were born within six months of each other in 1901. Both lived to within sight of the century’s end: James died in 1989 and Lefebvre in 1991. And, as I argue in my Identities article, 'Passing through difference: C.L.R. James and Henry Lefebvre', their grappling with the times in which they lived led them to articulate a comparable politics.

What kind of politics? One which valued human flourishing more than formal equality. One which considered creative freedom more significant than technological progress. And one which found hope in the way in which ordinary people fought against constraint in their day-to-day lives.

‘And so it begins. India’s settler-colonial project has arrived’, reads the headline of The Medium on the 31st of October 2019. It must be noted that Indian setter-colonialism arrived through a longer colonial engagement, a brutal history of Indian denial of Kashmiri self-determination since October 1947.

On the 5th of August 2019, the Indian government executed a legally questionable constitutional annexation of the state of Indian-administered Jammu and Kashmir after placing Kashmiris under an unprecedented digital and physical lockdown, a military siege. Kashmir’s semi-autonomous status has long suffered what Duschinski and Ghosh have called a process of occupational constitutionalism. The Jammu and Kashmir Land Reorganisation Act 2019, enacted on the 5th of August, came into effect on the 31st of October 2019. Kashmiris, whose right to determine their political future has been denied for 72 years, will now no longer have the right to exclusive ownership in their land. The Indian government has been busily attracting domestic and foreign investment. A member of the upper house of the Indian Parliament has called for Indian settlers from the armed forces to move into Kashmir. These settler-colonial moves further militarise and destroy an already fragile ecology. Caged physically and digitally, Kashmiris face a demographic change. The Indian state’s record of widespread extrajudicial killings, torture, sexual assault, enforced disappearances and mass graves over the last 30 years has been referenced by the Office of the United Nations’ High Commissioner reports of 2018 and 2019. The militarisation and the threat of demographic change have prompted the US-based Genocide Watch to issue a genocide alert for Kashmir.

It may be a truth not so universally acknowledged that editing a special issue of a journal can often be a nerve-wracking affair. Guest editing a special issue for Identities titled 'Archives of Coloniality and Solidarity: Kashmir and Palestine, in medias res', goes beyond this experience. The razored concertina wires, the militarised checkpoints, the open brutality, the violence against the living and the dead, and the permanent warfare against entire populations that characterise the experiences of Palestinians and Kashmiris permeate this special issue. These experiences may not be exceptional to those editors and authors working on state violence and occupations. However, the experience itself must be acknowledged.

Author emails in the summer of 2019 demonstrate the porous ways in which the occupations of Palestine and Kashmir have pervaded this guest editing process.

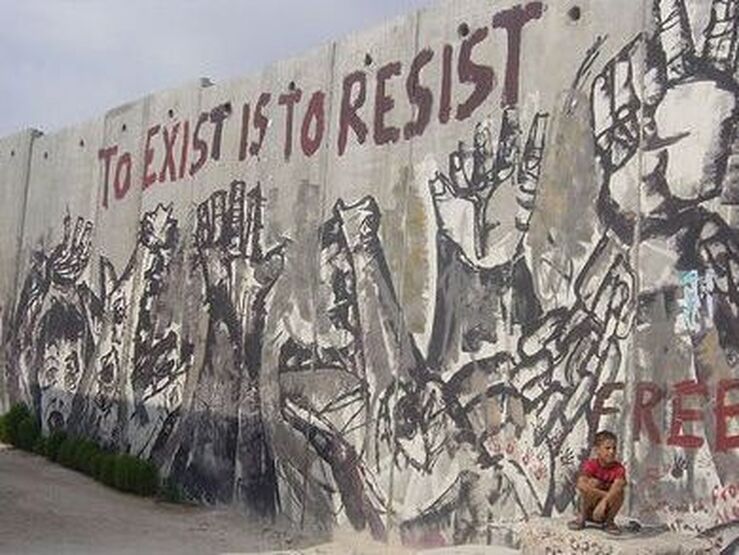

I have been researching the activism of Israeli radial leftist movements for a decade now. Travelling to Palestine-Israel throughout the past years, speaking to activists and observing protests prompted me to examine the role of Jewish-Israeli activists in resisting the occupation and colonisation of Palestine. My empirical research on the Anarchists Against the Wall contributes to a growing body of activist-scholarship which highlights the emergence and consolidation of decolonial co-resistance (as opposed to the accommodative notion of co-existence) as an increasingly important aspect of joint Palestinian and Jewish-Israeli activism since the outbreak of the Second Intifada.

In 2003 during the Second Intifada Israel made a unilateral decision to build a wall beyond the Green Line in response to Palestinian militancy in order to protect Israeli civilians from political violence. The separation wall was built largely on Palestinian land, circling and incorporating the illegal Israeli settlements into Israel-proper, directly undermining the borders of the two-state solution. The building of the wall promoted widespread Palestinian resistance including weekly Friday demonstrations in the villages affected by the wall, raising international awareness, petitioning the Israeli High Court against village land confiscations and petitioning the International Court of Justice which ruled the wall’s construction in violation of international law in 2004. In many respects, the Palestinian struggle against the wall is a continuation of the Palestinians’ long-established tradition of non-violent resistance and civil disobedience against the Occupation.

Canada and the United States are touted as multicultural societies, both formally through multiculturalism policies and informally through cultural narratives and metaphors such as the 'melting pot.' Still, these policies, narratives and metaphors can actually mask persistent inequalities that immigrant populations must navigate through, even for populations that already appear well-equipped to adapt to the host culture.

This is the case for Filipina/os. In my Identities article, 'The centrality of neoliberalism in Filipina/o perceptions of multiculturalism in Canada and the United States', Filipina/o university students in Toronto and Los Angeles discuss their views regarding ethnic identity maintenance and inclusion in their respective environments. The results were a bit counter-intuitive. |

|

Explore Identities at tandfonline.com/GIDE |

|

The views and opinions expressed on The Identities Blog are solely those of the original blog post authors, and not of the journal, Taylor & Francis Group or the University of Glasgow.