|

|

Handsworth and the production of knowledge: Blackness, racism and anti-imperialism in 1970s Britain27/11/2019

The African Caribbean Self-Help Organisation (ACSHO), based at Heathfield Road in Handsworth, Birmingham, established itself as a central hub for Pan-African centred learning and intellectual debate in the early 1970s. ACSHO members were part of a UK-wide co-ordinating committee that sent a delegation of activists to the 6th Pan African Congress (6PAC) in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania in 1974. My Identities article, ‘Each one teach one’ visualising Black intellectual life in Handsworth beyond the epistemology of ‘white sociology’, shows how the conference statement by the UK delegation at the 6PAC meeting was critical of the inherent racism of their social condition in England’s metropolitan cities as well as of the racist ways they were being studied by white social scientists at the time. Through their own Pan-African centred and anti-colonial critique, the delegation used ‘scientific socialism’ to situate their political struggle within a global context of anti-imperialist resistance movements.

Inside this hive of Black intellectual activism emanating from Birmingham, the archival work of Vanley Burke is particularly noteworthy. Born in St Thomas, Jamaica in 1951, Burke recalls receiving a gift of a camera sent by his mother from England for his 10th Birthday. He became fascinated by the ‘magic of photography’ and was compelled by both the science and artistry of this medium (Sealy 1993). Since the early 1970s, Burke has documented the lives of Caribbean communities in Birmingham with an intimacy and sensitivity towards the people he shares the city with.

0 Comments

A couple of years ago, I shared a paper-in-progress with some colleagues. I got a lot of wonderfully kind and collegial feedback, but I noticed that something was amiss between my own home base of sociology and other disciplines that theorise emotion. At the mere mention of the name Lauren Berlant, two people reeled back in their chairs, rolling their eyes and groaning in exasperated derision. The centring of Stuart Hall's work in my paper perplexed one colleague, who explained that 'we've transcended Hall with Pierre Bourdieu and Jeffrey Alexander'.

Bourdieu and Alexander, I couldn't help noticing (especially by contrast to Hall), are decidedly less adequate for understanding race and, to a lesser extent, gender. And unlike Bourdieu and Alexander, who are claimed in the name of sociology, Hall and Berlant can be considered cultural theorists, though they've significantly influenced social theory. The encounter I've just described sits where these two terrains of struggle meet: disciplinary politics and politics more broadly. I want to suggest that it would be fitting to bring the same principles that guide better political praxis into our inter/disciplinary engagements. The haste with which some sociologists of emotion dismiss interdisciplinary fields such as cultural studies, critical race studies, and postcolonial studies is in one sense perhaps not surprising. Despite the significance of emotion in the organisation of every aspect of social life, keyword searches for recent publications on emotion within prominent journals in these fields produce surprisingly scant results. Other concepts, such as 'attitudes' and 'lived experience', feature more prominently. For emotion theorists seeking an excuse to bypass interdisciplinary work, the lexical differences seem sufficient. 'There's nothing relevant for me here. This isn't how “we” do it.'

The external definitions we are given, i.e. how others define us, become an inescapable part of our internal self-definition. Such external labelling is more effective if it is done with institutional legitimacy and governmental authority. This separation of a population into ‘us’ and ‘them’ can have serious consequences for people from subordinated groups.

A clear example of this kind of external labelling can be observed in the frequent reports of the Swedish National Agency for Education concerning 'educational underachievement' of students with foreign background in Sweden. This labelling primarily indicates a negation of everything ‘Swedish’. According to this understanding of Swedishness, not all of those who were born or brought up in the country are Swedes. A Swede is born of parents who are native-born ‘Swedish’, has a ‘Swedish’ appearance and name, and speaks Swedish without a foreign accent. Secondly, in these reports, the offspring of immigrants, a very heterogeneous population in terms of country of origin, class background, length of residence in Sweden and age at arrival, are lumped together as one homogenous group and labelled 'students of foreign background'. What the recipients of these reports (which are widely broadcast in the media) understand is that these students always lag behind those of 'Swedish background', thereby putting a strain on Sweden’s educational system. Such descriptions hide the internal variability between young people in these categories. and indicate the ‘racial inferiority’ or ‘cultural backwardness’ of young people with an ‘immigrant background’. This also fails to take into account the growing proportion of young people with migrant parents who do not define themselves (at least not initially) by their migrant background.

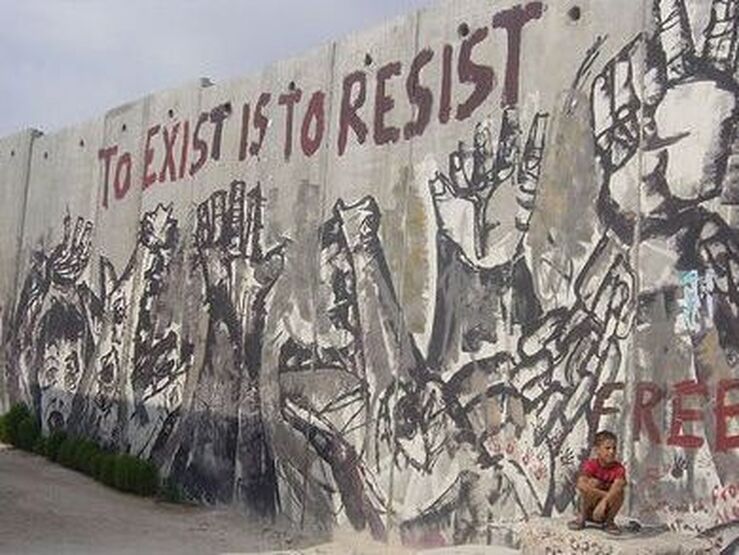

I have been researching the activism of Israeli radial leftist movements for a decade now. Travelling to Palestine-Israel throughout the past years, speaking to activists and observing protests prompted me to examine the role of Jewish-Israeli activists in resisting the occupation and colonisation of Palestine. My empirical research on the Anarchists Against the Wall contributes to a growing body of activist-scholarship which highlights the emergence and consolidation of decolonial co-resistance (as opposed to the accommodative notion of co-existence) as an increasingly important aspect of joint Palestinian and Jewish-Israeli activism since the outbreak of the Second Intifada.

In 2003 during the Second Intifada Israel made a unilateral decision to build a wall beyond the Green Line in response to Palestinian militancy in order to protect Israeli civilians from political violence. The separation wall was built largely on Palestinian land, circling and incorporating the illegal Israeli settlements into Israel-proper, directly undermining the borders of the two-state solution. The building of the wall promoted widespread Palestinian resistance including weekly Friday demonstrations in the villages affected by the wall, raising international awareness, petitioning the Israeli High Court against village land confiscations and petitioning the International Court of Justice which ruled the wall’s construction in violation of international law in 2004. In many respects, the Palestinian struggle against the wall is a continuation of the Palestinians’ long-established tradition of non-violent resistance and civil disobedience against the Occupation. |

|

Explore Identities at tandfonline.com/GIDE |

|

The views and opinions expressed on The Identities Blog are solely those of the original blog post authors, and not of the journal, Taylor & Francis Group or the University of Glasgow.