|

|

|

Blog post by Shereen Fernandez, London School of Economics, UK

Right now in the UK, the topic of ‘extremism’ is once again gripping public consciousness. On 14th March 2024, Michael Gove MP, the communities secretary, unveiled a new government definition of extremism, which is: ‘the promotion or advancement of an ideology based on violence, hatred or intolerance, that aims to:

The unveiling of this new definition of extremism aims to target groups and individuals who, if defined as an extremist, will be blocked from engaging in government, working in public bodies, and receiving council grants. Extremists are not considered as lawless per se, meaning that they cannot be prosecuted but instead, are considered to be ‘unacceptable’ by government. Of course, any designation of extremism will have a direct impact on how such groups and individuals can operate in other spaces of significance, such as in religious institutions, where claims of hosting ‘extremists’ will set them back significantly. As shown in my Identities article on Prevent in schools, ‘When counter-extremism ‘sticks’: the circulation of the Prevent Duty in the school space’, the label of ‘extremism’, for Muslims especially, is part of a long trajectory dating back to 9/11 which saw their significant securitization globally as a result of labels like this.

0 Comments

Blog post by Nasar Meer, University of Glasgow and co-Editor of Identities: Global Studies in Culture and Power

One of the subplots emerging from the 2024 General Election is to be found in talk of the ‘Muslim vote’. This is said to have been mobilised against the Labour Party, in protest at its position on Gaza, in constituencies with a sizable Muslim electorate. The success of Independent candidates such as Shockat Adam, a local resident in Leicester South who overturned a 22,000 majority of the incumbent shadow cabinet member Jonathan Ashworth, certainly came as a surprise. While prevailing MRP (multi-level regression and post stratification) models generally proved accurate in translating polling data into seat predictions, with some exceptions, they also reproduced a longstanding problem about the under polling of minority groups, which elsewhere missed that 23-year-old first time campaigner Leane Mohamed would in Ilford North come within 528 votes of unseating the new Health Secretary, Wes Streeting.

Blog post by Aino Korvensyrjä, University of Helsinki

In the first week of May 2018, there was some moral panic in the German media. National and regional media reported on a ‘mob’ of 150–200 black Africans violently stopping deportation and attacking the enforcement patrol in a reception centre for asylum seekers in Ellwangen, Baden-Württemberg. After the 2015 ‘Summer of Migration’, when popular sympathies for refugee-migrants had peaked in Germany, such narratives of dangerous black and brown refugee-migrant men were a standard feature in the German media and public debate. This continuous panic created public acceptance of deportations of asylum seekers and the increasingly ruthless control policies at external EU borders. My Identities article, ‘Criminalizing black solidarity: Dublin deportations, raids, and racial statecraft in southern Germany’, looks beyond the media and policy debate on ‘Ellwangen’. It examines how the police and courts managed local conflicts over deportation during an intense campaign to increase so-called Dublin deportations. These are deportations to the first country of entry in Europe. For the authorities, a fingerprint registered into the EURODAC database by another European country is enough to begin the deportation proceedings. West Africans were then a key target group of Dublin deportations, and Italy was the main country of destination. The article draws attention to a series of police raids targeting West African migrants living in southern German asylum camps in 2018, including the above-mentioned raid in Ellwangen. In all cases, police accused West African men of rioting against deportation enforcement to Italy, and local courts prosecuted numerous individuals. My article explores how the police and local courts thus suppressed anti-deportation protests and how their practices produced race.

Blog post by Vadricka Etienne, University of Nevada, Reno, USA

Each year, my immigrant father embarks on a summer trip to Haiti. A lump jumps into my throat as he prepares for his journey. He’s excited to return home, but I fear for his safety. This fear grows yearly, and my anxiety spikes whenever he doesn’t answer the phone. My thoughts race to the worst-case scenarios, mainly because we’ve discussed what to do if he was kidnapped. While the rising gang violence demanded that he skip his trip last year, he would not miss another. I understand because he is at peace when in Haiti. But I find myself taking deeper breaths only when he lands in Miami, making his way home. During the summer, I consumed conflicting media reports. Mainstream media catastrophized the gang terror, while Haitian content creators shared the mundane, such as dinners out on the town, demonstrating that the violence was not everywhere in the county. These contradictions encapsulate how the children of immigrants could have a fragile relationship with their parents’ birthplace as they often experience the country through the lens of others, very rarely their own.

Blog post by Ashlee Christoffersen, Aerin Lai and Nasar Meer, University of Edinburgh, UK

RACE.ED and Identities: Global Studies in Culture and Power have published a new collection of essays exploring racial justice work in higher education, titled Advancing Racial Equality in Higher Education. The collection follows on from the event “Racial Equity Work in the University and Beyond: The Race Equality Charter in Context”, which explored what racial equality means in higher education and was organized following publication of the report of a large-scale review of the Race Equality Charter. Advance HE’s Race Equality Charter (REC) is a UK wide programme that began in 2016 aiming to improve the representation, progression and success of Black, Asian and minority ethnic staff and students[i] within higher education. REC is one tool for addressing racial injustice in higher education institutions.

Recent UK Home Secretaries have condemned the toppling of a slave trader statue in Bristol, dismissed footballers taking the knee as ‘gesture politics’ and called on police forces to spend less time on diversity and inclusion initiatives. Yet between 2010, when the Conservatives came into power, and 2020, the overall policy framework remained broadly favourable to multiculturalism: accommodations are still made for ethno-religious dress, the BBC has retained its mandate to reflect diversity, and funding is available for ethnic organisations.

With respect to immigration, there has been a closer connection between harsh rhetoric and restrictive measures, exemplified by the multiplication of immigration checks, the end of free movement with the EU, the housing of asylum seekers in inadequate and overcrowded military barracks and the on-going attempt to deport some to Rwanda. At the policy level, therefore, efforts to include racialized citizens seem to have become disconnected from the opening of the country to foreign nationals. Shift the focus from the Government to minority ethnic and anti-racist organisations, however, and the picture starts to look quite different. In September last year the Muslim Council of Britain echoed a report from the Institute of Race Relations denouncing how British Muslims were disproportionately affected by the citizenship deprivation powers reinforced through the Nationality & Borders Act 2022. The Runnymede Trust, a leading race equality think tank, has published a number of blog posts denouncing deportations and asylum-seekers’ woeful living conditions, partly due to the denial of their right to work and access public funds. Similar claims have been raised by Voice4Change, an advocate for the Black and minority ethnic voluntary sector.

After China turned into a popular migrant destination, foreign-Chinese couples became a common sight on the streets of Chinese cities. In my early years of living in China, as a language student in Beijing (2005-2009), I already developed an interest in the romantic relationships I would later study as an anthropologist. My circle of friends included many Chinese-foreign couples, and our love lives were a favourite topic of conversation. These conversations were often marked by circulating beliefs about dating in Beijing for foreigners, such as the idea that Chinese women liked white men, but white women did not like Chinese men. This idea was both widely shared and regularly challenged by couples who proved the opposite. We also debated the contentious position of the white man in the Beijing dating scene. Was he wildly popular for being perceived as rich, handsome and worldly by Chinese women? Or was he regarded with suspicion for possibly being a player or a benguo luse (本国卢瑟)? This term translates to ‘loser back home’ and is popularly used to undermine the admiration that is perceived as being extended to white men too easily.

The Facebook group for my local area in Manchester generally has messages about missing cats and people looking for recommendations for plumbers. But there are also messages asking ‘what is it like to live in the area’ from people thinking of moving there. This is a very ethnically mixed, relatively deprived area which has an equally mixed reputation. The responses to the queries often refer to reputational issues – and ones of history, suggesting that the area has/has not changed over time. The live nature of histories of place and the ways in which stories about places are frequently racialized is what colleagues and I were concerned with in our recent Identities article, ‘Histories of place: the racialization of representational space in Govanhill and Butetown’. We were interested in considering the racialized nature of Henri Lefebvre’s[1] conceptualizations of spatial tactics, representations of space and representational space – including in the way they are marked by the past.

We examined interviews with local activists, community representatives and professionals working in the areas of Butetown in Cardiff and Govanhill in Glasgow which were part of a study of the dynamics of ethnic inequalities for the Centre on the Dynamics of Ethnicity (CoDE). Both areas have long histories of immigration and, as representational spaces, have often been highly racialized. They have been shaped by industrialization, empire, de-industrialization and then some subsequent regeneration.

Cross-posted by RACE.ED

‘We are now in the age of Du Bois’, declared Aldon Morris in his widely acclaimed study, The Scholar Denied: W. E. B. Du Bois and the Birth of Modern Sociology. In this, Morris meticulously charts the intellectual contribution of Du Bois (1868-1963) to the social sciences broadly conceived, and sociology in particular, to argue that this remarkable figure could no longer been treated as peripheral, or an ‘add on’. After all, few sociologists pioneered as much as Du Bois, including in, amongst other areas, both quantitative and qualitative methodologies, especially social statistics and urban ethnography, reconciling questions of political economy with social movements (not least in charting the suppression of Atlantic slavery), as well as foregrounding relationships between the self and society, and doing so in ways that prefigure questions later posed in the politics of recognition. For these reasons I am not alone in arguing that Du Bois has bequeathed to sociology a cluster of normative categories that compel us to move beyond a kind of formalistic inquiry, and through which we might be more open to uncovering sometimes submerged features of social life (1).

After living in Miami, Florida, for several years, Mother Frances Butler returned to her home in Nassau, Bahamas and founded the Mother’s Club, which provided social welfare support to the Bahamian Black community. Along with similar groups, the organization offered a variety of social services where they fundraised as a part of hurricane recovery, aided the war effort and offered health and other social services for women and children. In 1937, Mother Butler changed the title of her organization to The Young Women’s Christian Association.

The building that formerly housed the Mother’s Club sits at the corner of Goal and East Street in the heart of Nassau. The building is in the Grants Town community and was originally established by the Bahamian government to house freed people and Liberated Africans in the early 1820s. This area is one of the communities located in what is known as the ‘Over the Hill’ neighbourhoods in Nassau. These neighbourhoods became a rich site of Black life during the 19th and 20th centuries, as Black people in the Bahamas encountered poverty and racial oppression. Mother Butler also founded other Black-led organizations, including the Young Men’s Christian Association and the Silver Bells.

Discussions of contemporary white supremacy are seemingly everywhere: the election of Donald Trump and the January 6th insurrection, the murder of George Floyd, Brexit, the rise of the Alternative Right and white supremacist violence, and the coordinated efforts to deny racism and not educate children about the history and contemporary reality of race. These loud and important flashpoints, however, can unintentionally obscure the wider function and embodiment of white supremacy. That it is global and interconnected, is about systems and structures of power and not individuals, often hides in plain sight, and does not need ‘white’ bodies to sustain its power and replication.

For over a decade I have travelled to collect field data on race, globalization, development and labour in different Global South geographies. Through these engagements similar patterns became clear: countries in the Global South were beholden to policies dictated by the Global North. National groups racialized as white, or that exhibited a proximity to whiteness, were typically in positions of political and economic power. Those racialized as Black, or represented a distance from whiteness, had the worst material conditions. These seemingly very apparent global racial inequalities were often understood, though, as not about racism but about economic development, skills, capabilities, culture – essentially, anything but race.

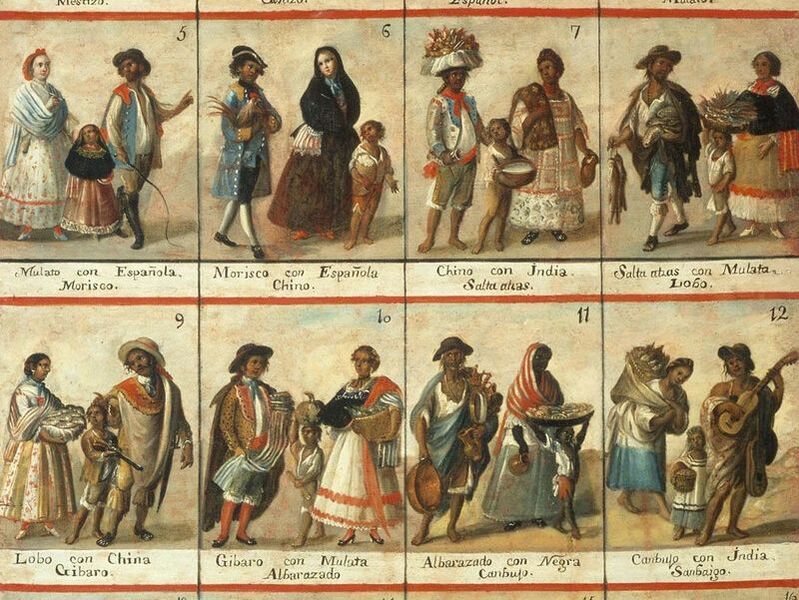

‘What are you?’ When posed with this question in highly racialised societies, most people respond by sharing their racial identity. Although racial identity is a personal decision, the choice is often constrained by the recognised racial categories available within the racialised society.

For example, as written into law through the 1950 Population Registration Act – linchpin legislation that helped set in motion South Africa’s Apartheid system by defining race for its population – to be Coloured was to be ‘a person who is not a white person or a native’ Black/African. To be Coloured meant you were neither/nor. We are now a quarter century into post-Apartheid South Africa and the state has undergone a massive sociopolitical transformation that operates under the ideal to be non-racist. Some changes include the repealing of Apartheid laws, including the Population Registration Act. So how has the transition from the white supremacist Apartheid state impacted Coloured racial identities in post-Apartheid South Africa? I explore how racial identities are created and recreated to adapt to state-level racial (re)formation processes in my recently published Identities article, ‘Able to identify with anything’: racial identity choices among ‘Coloureds’ as shaped by the South African racial state’.

The use of identity markers in sport has received considerable attention from scholars in a number of disciplines over a number of decades. This has been looked at in a variety of different sports and includes insightful studies published in Identities such as the works of Paul Campbell and Daniel Burdsey on football and Constancio Arnaldo on boxing.

In our Identities article, ‘Pretty fly for a white guy: The politics of race, nation and difference in professional boxing’, we look at the ways in which race and nation are (re)presented within the coverage of one particular fight. Boxing is a sport that relies heavily on binary divisions. In his book Boxing and Society, the sociologist John Sugden noted how success in the ring could ‘symbolise not only individual achievement, but also racial and national superiority’. For the promotion of many championship bouts the hype around the fight is constructed around binary oppositions. This paper looks at the bout between Joe Calzaghe (a white boxer from Wales) and Bernard Hopkins (a black boxer from the USA) as a case study to explore the representation of identities. In attempting to tease out some of the key themes to emerge in the intersection of race and nation, we tried to understand how identities are portrayed within boxing. This work also highlighted further differences around the understanding of social class and core/periphery relations within a particular sport.

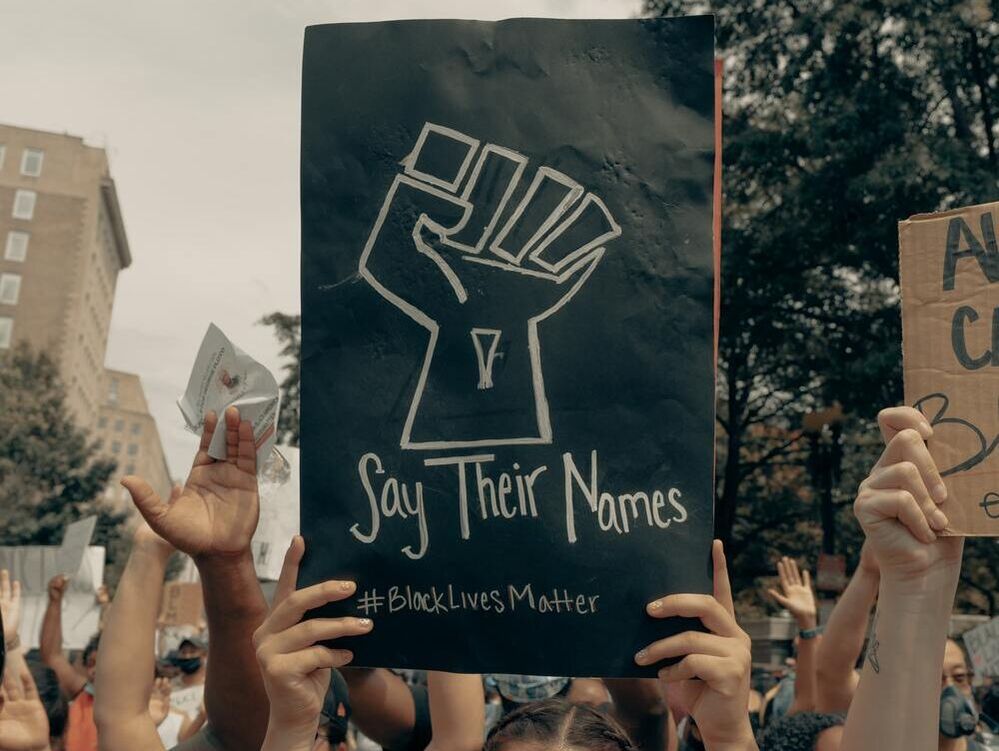

The murder of George Floyd in the spring of 2020 sparked an outcry against police brutality and racial injustice in the United States. In the wake of the killing, support for the Black Lives Matter movement rose sharply among white Americans. Shows of support ranged from the (controversial) posting of blacked-out photos on Facebook and Instagram, to patronage of black-owned businesses, to marching in BLM protests.

We are now more than a year out from George Floyd’s killing. Much of the antiracist fervour expressed by progressive white Americans in 2020 appears to have fizzled. According to a Politico/Morning Consult poll, the percentage of white Americans with positive evaluations of the Black Lives Matter movement has declined significantly since last summer. Some see this change as an indication of the superficiality of many white Americans’ involvement in antiracism. While this may be true, our Identities article, 'Racemaking in New Orleans: racial boundary construction among ideologically diverse college students', points to the important role of racial boundary construction in limiting white Americans’ involvement in antiracist efforts.

In majority white countries, the Black Lives Matter protests that unfolded after the murder of George Floyd were accompanied by the intensification of public debates on systemic racism and white allyship. Some media focused on Black-white couples, discussing the impact of these events on white partners’ understanding of anti-black racism in their Black partners’ lives. As part of the ERC-funded project ‘Regulating Mixed Intimacies in Europe (EUROMIX), over the past four years I have explored Black-white couples’ experiences of racism and discrimination in their everyday lives.

Drawing from ethnographic fieldwork I conducted in 2018-2019, my Identities article, ‘Interracial couples and the phenomenology of race, place and space in contemporary England’, looks at partners’ perceptions of dis/comfort and un/safety across different contexts: when they jointly move in public spaces, choose where to make home, and travel for leisure. By juxtaposing these scenes, the article foregrounds a multi-layered economy of constraint and choice underpinning the lives of the opposite and same-sex couples that I have met and/or interviewed.

Cross-posted from RACE.ED

It has been widely reported that the COVID-19 pandemic has disproportionately impacted Black and Ethnic Minority (BAME) communities across the UK, which have suffered higher rates of hospitalisation and mortality. While the causes of this outsized impact are yet to be fully untangled, it is consistent with longstanding disparities in health outcomes and access to medical treatment between BAME communities and the white majority. The pandemic has, in effect, brought pre-existing health inequities to the fore. With all our hopes for overcoming the pandemic resting on the success of our vaccination programme, it is essential that the jabs being put into arms have been shown to be safe and effective for people across the entire spectrum of our ethnically diverse population. This is important for two reasons. First, medical treatments can have varying effects for people of different ethnic backgrounds, and hence it is essential that clinical trials include volunteers that are representative of the different groups that make up our population. Second, people from BAME backgrounds deserve the same opportunity to build trust in vaccines. This means knowing that vaccines have been rigorously tested on volunteers from their own communities, as well as other groups.

While never entirely going away, the relationship between football fandom and racism has over the past few months come into renewed focus. In a UK context, this concerns the continued controversy over players choosing to ‘take the knee’ before professional matches in protest of racial injustice, as well as online abuse targeting the three black players who missed penalties in this summer’s final of the Euro 2020 tournament. Against a back story of overt racism in English stadia throughout the 1970s and 1980s, these episodes remind us of the need to keep interrogating the use of racist language across English football.

In this context Millwall FC holds a somewhat unique, although unwanted, position. It is a club that is widely recognised – for its association with racist hooliganism – even among those who know little about football. This reputation dates back to the 1970s. Therefore, the idea of the black Millwall fan – as a category and an identity – causes raised eyebrows, as it appears an oxymoron that goes against existing perceptions of what constitutes a Millwall fan. It is the oral histories of black Millwall fans and players that are at the core of the Millwall's Changing Communities Research Project, funded by the Lottery and led by the South London-based charity Bede House.

Cross-posted from Georgetown Journal of International Affairs.

Recent events in France have revealed how race remains such a loaded concept in French society. But policymakers must emphasize that this is nothing new, and that public policies need to address historical and present racism in France in order to move forward. Events in recent months have once again made race and racism part of public debate in France. There was the beheading of school teacher Samuel Paty in a banlieue, or suburban outskirt, north of Paris in October 2020. Then the beating, captured on video, of Michel Zecler, a forty-one-year-old Black music producer, by four police officers last November in Paris. These debates have even included accusations of importing Anglo-American or US conceptions of race and racism to the French context, as evident in a recent interview with President Emmanuel Macron in the New York Times and movement by his administration to investigate French universities for importing American theories. This is in addition to a proposed bill making it a criminal offense to share images of police officers on social media platforms, amid a growing mobilization against police violence targeting Black and Maghrébin-origin individuals.

You might reasonably wonder what Muay Thai or Kickboxing has got to do with race or division? Or what the niche sports of Muay Thai and Kickboxing are in the first place. Muay Thai is a combat sport originating from Thailand that evolved out of 17th-century warfare techniques and now incorporates punches, kicks, knees, elbows and clinching. Kickboxing has a similar ruleset, albeit elbows are illegal and clinching is limited. Training within both sports is an embodied practice that requires intimate bodily contact between training partners.

My Identities article, ‘Fighting with race: complex solidarities & constrained sameness’ (and the broader doctoral project it derives from), draws upon ethnographic field work and my experience training to compete in Muay Thai. Within the article, I explore how fighters seek to construct one another as the same, as fighters, as they disavow race and problematise prior notions of gender and masculinity (alongside other identity markers). In part, the disavow of gender and masculinity was enabled by the presence of female fighters, which contrasts with boxing gyms that are notable for the exclusion of women and/or for taking their fighting ambitions less seriously. Thus, whilst remaining a ‘hyper-masculine’ space, I foreground three factors that enable people to argue for contingent sameness.

Due to the accessibility of the internet and the ability of online spaces to bring people together, platforms like social media sites and web forums have allowed globally dispersed communities to engage in conversations about identity and belonging. For my Identities article, ‘Connectivity, contestation and cultural production: an analysis of Dominican online identity formation’, I collected and analysed text data from a web forum that I call ‘DRLive’ to show the kinds of identity discourses that happen online. This site caters to all things Dominican Republic, with free and open forum pages where Dominicans and non-Dominicans participate in discussions covering numerous topics. Adding to work on diaspora, migration, and cultural production among Dominicans, I propose forums and other virtual spaces as additional sites where diasporic and non-diasporic Dominicans come together to talk about and challenge evolving interpretations of identity, history and cultural memory.

Cultural memory, which is defined as a collection of commonly shared historical moments and experiences, is passed on and shared over time by members of a nation. In the case of this forum, for example, I find that ‘the contrived historical narratives propagated in the Dominican Republic throughout the 19th and 20th centuries continue to inform how Dominicans in the country and in the diaspora interpret and construct Dominicanidad.’ Work on virtual spaces often seeks to address how migration might affect the maintenance of cultural memory, especially as second- and third-generation immigrant communities emerge far from their homeland.

Following George Floyd's horrific death and the scenes of his sensational courtroom trial which played out to public scrutiny across the world, my recently published Identities article, 'The dying Black body in repeat mode: the Black 'horrific' on a loop', addresses the notion of the recurrence of 'Black death' in repeat mode offline and its viral circulation online in the digital economy.

Digital platforms abstract dead bodies as floating matter to be consumed without context. In tandem, this 'repeat mode' produces a visuality or a 'shadow archive' to showcase Black bodies as perpetually given over to brutality, violence and foreshadowed by the possibility and actuality of constant death. The horrific killings of Blacks is sustained through police brutality against the historic context of slavery, White oppression, segregation, Black civil rights movements and an American dream forged through Black death as part of a visual regime. My article opens up with the question from a Black student posted on a research mailing list online, on the troubling phenomenon of consuming Black bodies in demise in repeat mode on the internet. The student's query bridges a number of issues including the role of the digital sphere as a virtual graveyard in shaping Black consciousness and communion, given the internet's 'body snatching' tendencies in which violence, death and bodies struggling to 'breathe' float infinitum.

Cross-posted from The Conversation.

On BBC Sport, Match of the Day pundits Ian Wright and Alan Shearer recently had a conversation about racism in football. Shearer, the white ex-England international striker asked his black ex-teammate Wright: “Do you believe a black guy gets treated differently to a white guy?” Wright’s response was unequivocal: “Without a doubt, Al!” Black players face discrimination on every level: public (anti-black racism from fans in stadiums), private (abusive DMs on social media) and institutional (lack of management and coaching opportunities). Wright, however, also pointed to the disparate treatment players receive in the press, referencing recent reports on similar property investments by strikers Marcus Rashford and Phil Foden. Rashford, who plays for Manchester United and is black, was framed an extravagant, cash-rich, cash-loose footballer. Foden, meanwhile, who plays for City and is white, was described as the local Stockport boy looking after his family. Why do we need the 'racialized' in 'racialized capitalism'?[1] In his recent article for Field Notes,[2] Charlie Post insists on the need to think racism and capitalism together but is keen to move the discussion 'beyond racial capitalism' perspectives[3] because of disagreements about the spatial and temporal origins of racism, and about the explanation those perspectives offer for the reproduction of racism in capitalist societies. While there is much to welcome in Post's carefully-crafted account, there are four areas of disagreement to which I want to draw attention. First, whatever substantive critiques one might wish to level at racialized capitalism perspectives, it is premature to speak of going 'beyond racial capitalism' or to claim that 'the notion of 'racial capitalism' is redundant [because] there is no 'non-racial' 'capitalism,' without a more thorough consideration of the political and theoretical work these perspectives perform in the present moment. Post certainly acknowledges that they emerged out of the reverberations of collective action against state racism, particularly the desire of a new generation of activists to make sense of racism's continuing power to inflict damage and death. However, there is much more that needs to be said on the matter. In particular, racialized capitalism perspectives help make transparent the constitutive role racism played in the formation and reproduction of capitalist modernity. This is no mean achievement, given that much of public discourse, along with liberal and critical thought, continues to minimize and underestimate its structuring power and significance.

In an age defined by hyper-visibility made possible by always-on digital media, brought to our fingertips by the smartphone, we are regularly fed images of (often extreme) racial violence. The circulation of the long eight minutes and forty-six seconds of George Floyd’s murder by Minneapolis police officer, Derek Chauvin, in May last year reinvigorated a movement across the Global North, against the disposability of Black lives. However, there is no simple way to untangle the dilemma that there is a seeming need to witness the death of a Black person to trigger a response. As LeRon Barton wrote, ‘watching Black men being beaten on video is the new lynching postcard.’

Despite the energy unleashed by the Black Lives Matter protests of 2020, it is not surprising that many antiracists remain sceptical about the lasting commitment of those momentarily inspired by the uprising. Will 2020’s #BLM moment be superseded by a return to scrolling through images of racial violence to which we seem increasingly immune? These questions animate my Identities article, ‘Looking as white: anti-racism apps, appearance and racialized embodiment’, which looks at mobile apps for reporting on and educating about racism. As mobile technology is such a part of our everyday experience, it can clearly be a powerful tool for pedagogy. This is the aim of one of these apps, the Australian-based Everyday Racism app. The app encourages ‘bystanders’ to learn about the experiences of people of colour and Aboriginal people who face racism in their daily lives. It uses gamification to deliver text and video messages to app users about these experiences in the aim of building empathy and encouraging what Australian racism researchers call ‘bystander antiracism’ (a strange appropriation of a concept used to describe those who stood by and did nothing during the Nazi deportation of the Jews).

The territorial realization of the Israeli state produced a new category of stateless people: Palestinian refugees. Those expelled from their homes, villages and land during the onset of the Nakba (catastrophe): a large scale ethnic cleansing process executed in 1947-48 Palestine, has resulted in the creation of one of the largest and longest standing protracted refugee communities world-wide today. The unresolved question of Palestinian displacement raises important considerations in, what scholars of redress have named, an era of settler colonial reparations. One line of inquiry that remains relevant for thinking about the future of redress to Palestinian displacement is the following: How did an Indigenous Palestinian society with historical ties to land come to be internationally governed as refugees external to the land? Further, how might we think about the history of redress and humanitarianism in the early years of Palestinian displacement as one tied to a broader genealogy of race and settler colonial formations in Palestine?

|

|

Explore Identities at tandfonline.com/GIDE |

|

The views and opinions expressed on The Identities Blog are solely those of the original blog post authors, and not of the journal, Taylor & Francis Group or the University of Glasgow.