|

|

|

Blog post by Christian Lamour, Luxembourg Institute of Socio-Economic Research, Luxembourg

Late modernity in the European Union is characterized by the return of ‘hot nationalism’, with a growing number of citizens supporting radical right parties and leaders. These political entities and personnel have hammered out an electoral winning, ‘nation-first’ agenda, which is notably marketed as protecting the cultural identity and cohesion of a national people, jeopardized by alien threats. This vivid return of national cultural identities in the agenda of European states has appeared at a time when relationships between EU member states have been remarkably peaceful for generations, whereas their main long-term heritage has been the reproduction of national conflicts, territorial gains and momentary stabilization of borders following treaties torn apart in subsequent wars. The cultural enemies defined by today’s EU radical right within specific nation states are not neighbouring nations, but communities, the identities of which are represented as external to the world of nations. This means the elites are characterized as Europeanized/globalized, whilst the non-European migrants are racialized as oriental/African entities replacing the European national identities with the support of the globalized elite.

0 Comments

Blog post by Ioana Vrabiescu, Vrije University Amsterdam, Netherlands

In my Identities article, ‘Detention is morally exhausting’: melancholia of detention centres in France’, I invite the reader to reflect on two main issues: the perceived role of the law and the legal system and how these perceptions are translated into the organization of migration control. The perception of the law as fundamental to the state practices allows people to continue working alongside the migration control apparatus despite their beliefs that the law is not perfect. The tension in this context lies in the interplay between the perceived fundamental role of the law in the functioning of the state and individual beliefs about a deficient legal system. Despite these beliefs, individuals continue to work in the migration control apparatus based on their understanding of the law's fundamental importance. Within the migration control apparatus, I chose migrant detention centres as those sites that best reflect these ethical frictions, resulting in an atmosphere of melancholia.

Blog post by Bridget Anderson, University of Bristol, UK and Ioana Vrabiescu, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, Netherlands

The European Union presents itself as a global champion of human rights, yet its external borders are marked by hostility, surveillance and death. There is also an intricate network of borders within Europe that marginalizes and excludes migrants and asylum seekers. The vast majority of those excluded at the border and within Europe are people of colour. Two contemporary developments shape the context of our Identities Special Issue, Affective Control: The Emotional Life of (En)forcing Mobility Control in Europe – the global social movement for Black Lives and the COVID-19 pandemic. They have shaped conversations on structural racism and crisis-driven migration management and exposed the intersectionality of emotions and policies. For example, the invocation of national protection measures in the context of COVID-19 allowed European states to enforce border security under the guise of health protection, emphasizing the emerging pattern of governing migration through crisis management.

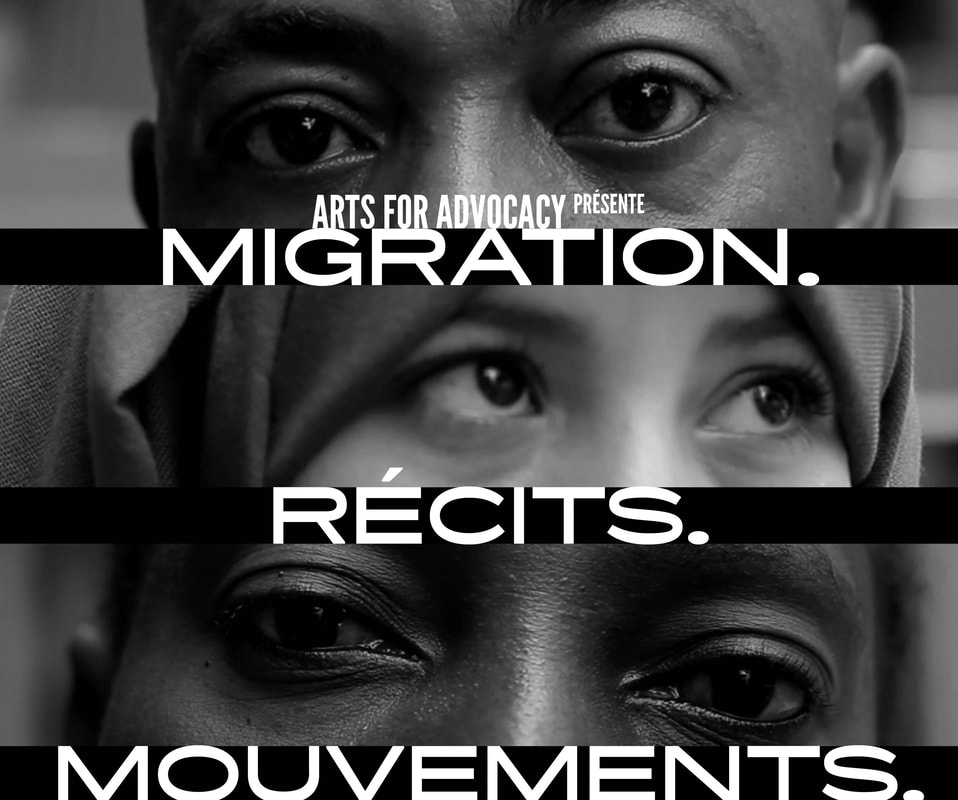

Blog post by Sebastien Bachelet, University of Manchester, UK and Mariangela Palladino, Keele University, UK

Overcrowded boats capsizing in the Mediterranean Sea feature regularly in the news. Yet, the discrepancy in the coverage and rescue efforts deployed for the boat carrying 750 people seeking safety which sank off the Greek coast, and the fate of the Titan submersible, is a stark reminder that vividly illustrates how some lives are more grievable than others. Talks of a migration ‘crisis’ moreover overlook the responsibilities and effects of European states’ hostile migration policies and violent bordering regimes. Public debates seldom scrutinize the political construction of migrants as illegal and undesirable, nor do they provide sufficient insights into people’s lives beyond abstract labels, especially south of the Mediterranean Sea, where European politicians propose to build asylum-processing centres. In this blog post, drawing on our Identities article, ‘Être vraiment vrai’: truth, in/visibility and migration in Morocco’, we focus on migration, creative processes and advocacy in Morocco, to demonstrate how narratives of migration that challenge expectations and demands for authentic and truthful migrants’ accounts can disrupt dominant and harmful forms of representation.

Blog post by Melanie Griffiths, University of Birmingham, UK

Political rhetoric around migration is often febrile. This has been especially evident in the UK in the last few years, with frequent talk of ‘crisis’ and ‘invasion’. Indeed, a government source in June 2023 described the small boats crossing the Channel as a ‘ticking time bomb’ threatening the UK’s social and economic security. Such discourse reflects an emotional turmoil of outrage and indignation, fear and panic, mistrust and repulsion. Alongside such splenetic rhetoric, however, the political response to irregular migration is also one of callous indifference and disregard. We see this lack of care demonstrated in the UK’s massive asylum backlog, with 170,000 asylum seekers now awaiting an initial decision. It is also reflected in the UK government’s plans to warehouse asylum seekers on boats and in military barracks, and to automatically banish new arrivals to Rwanda. These contradictory emotional displays act as a spectacle distracting from government failures to manage the immigration system effectively, but they have real-world impacts. This includes seriously and detrimentally affecting those navigating the immigration system, as well as wider societal impacts, with evidence of growing xenophobia and racially-motivated offences.

The arrival of large numbers of Ukranian refugees fleeing the Russian invasion to their country since February 2022 has been met with a wave of compassion and solidarity in most western European countries. However, critical voices have pointed out what has been perceived as hypocrisy, or a ‘double standard’, regarding attitudes towards refugees. Why are some of them welcomed with open arms, while others are being repressed at the border? While Ukrainians could fast-track their asylum claims and enjoy protection status with minimum requirements, people fleeing other conflicts in the Middle East and Africa were still getting stuck in lengthy bureaucratic processes and often becoming the object of resentment and discrimination in the host society. Is this so because of racial difference?

The increased arrivals of refugees in a short span of time reminded many in Europe of the peak of arrivals from Afghanistan and Syria in the mid-2010s. Public opinion in various western European societies of alleged unbridgeable cultural differences or difficulties towards ‘integration’ of the newly arrived did not apply to Ukrainian refugees. While Ukrainians, critical voices argued, were perceived in the mainstream public opinion as ethnically, culturally and racially close to western Europeans, other victims of armed conflict equally entitled to protection were still represented or perceived as ‘less deserving’ by social and political actors holding anti-immigration positions. This shows the extent to which the way migrants are portrayed in Europe is a highly contested matter that connects deeply to values, perceptions and anxieties permeating those societies. One glimpse at minority language protection: the fine line between empowering and segregating24/5/2023

On 5 November 2022, the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages celebrated its 30th anniversary. This charter lays down the principles for protection and promotion of minority languages and their use in education, cultural life, public services, and other sectors within the EU. Undoubtedly, such supra-national and similar national policies generally improve the rights and lives of minority members.

My Identities article, ‘Drifting borders, anchored community: re-reading narratives in the semiotic landscape with ethnic Lithuanians living at the Polish borderland’, discusses a concrete example of one such minority protected on national and supra-national levels – the national Lithuanian minority in Poland. I provide a glimpse into the realities of its members’ language use, identification and narratives of belonging. I learned that they find some official minority protection attempts more concerning than helpful.

During the 2019 debates around the introduction of the EU Settled Status (EUSS), which regulates the rights of EU citizens in the UK after Brexit, Labour MP Yvette Cooper described the scheme as a potential ‘Windrush on steroids’. The reference was to the ‘Windrush generation’ scandal, in which Commonwealth citizens, who arrived in the UK with a permanent right to stay, were classified as unauthorised migrants, deprived of the right to work, rent or access welfare, and in some cases deported. The Windrush generation scandal has focused on people who arrived from the Caribbean, and the publicly known cases and data on compensation applications show that Jamaica has been the single most common country of origin. However, it is not possible to determine precisely the extension and geographical profile of the scandal, also because of the initial refusal of the Home Office to review historical cases beyond the Caribbean to identify potential unjust treatments.

The Windrush generation scandal is mainly the result of the ‘Hostile Environment’ policy, which extends and multiplies controls of migratory status. As the Hostile Environment encourages targeting racialised groups, it can be seen as a continuation of the racism to which the Windrush generation has been subject since their arrival in the UK. The ambiguous status of those Commonwealth citizens – who arrived with British passports but less rights than the British-born, and the limited documentation of their status, made them further vulnerable to the injustices they underwent. The argument of the critics of the EUSS is that, as the status does not come with a physical document, and is digital-only, this endangers EU citizens in the UK to be in the future miscategorised and mistreated as happened with the Windrush generation. In my recent article for Identities, ‘The vulnerability of in-between statuses: ID and migration controls in the cases of the Windrush generation scandal and Brexit’, I use several documentary sources and interviews with EU citizens in the UK and British citizens in Belgium to explore the degree to which Brexit and the Windrush generation scandal pose similar questions in terms of ID and legal status.

On 7 March 2023, UK Home Secretary Suella Braverman, escalating the rhetoric on and punitive approach to migration, asylum and refugees, announced the ‘Illegal Migration Bill’ and strategy to stop migrants crossing the Channel in small boats by arresting, detaining, deporting and banning those caught. In response, former football player and BBC Match of the Day (MOTD) Presenter Gary Lineker tweeted that it is ‘an immeasurably cruel policy directed at the most vulnerable people in language that is not dissimilar to that used by Germany in the 30s’. The tweet led to a backlash in which responses ranged from the claim that he was operating beyond his remit as a sport presenter (as if they have not had to discuss racism and nationalism before), that he was in breach of the BBC’s impartiality rules, and that the comparison was unhelpful. Keir Starmer, Leader of the opposition Labour Party stated: ‘I think comparisons with Germany in the 1930s aren’t always the best way to make one’s argument’. Others took offense and expressed shock that anyone could associate Britain and the current government with the lead up and precursors to Nazism and the Holocaust. Some claimed that Lineker actually referred to these explicitly in his tweet, which he did not. Former Conservative MP for Stoke-on-Trent Jonathan Gullis claimed that Lineker was calling ‘people up here’, referring to Northern ‘Red Wall’ voters, which Starmer and Labour are also targeting with anti-immigration rhetoric, ‘racist bigots, Nazis’. According to Matthew Goodwin, Lineker’s comments are an example of how out of touch the ‘new elite are from the majority of the ‘people’ from the ‘Red Wall’ to ‘Tory Shires’, and particularly those at ‘the bottom’: ‘the white working class, straight men, non-graduates, and those who cling to more traditionalist views, such as supporting Brexit’.

From the institutions to the streets: the role of emotions in Barcelona’s migration control8/3/2023

In her essay The Cultural Politics of Emotions, Sara Ahmed raises the question: ‘What do emotions do?’, implying the social circulation of emotions. Even if felt by each individual in a unique way, emotions are addressed collectively, creating affective connections which in turn craft social realities.

There is a diverse range of institutions and practices that make up migration control in Barcelona. Despite the claim that it is governed by the rule of law, where there is no room for subjective or accidental decisions, emotions play a key role. What do a practitioner employed by a municipal institution in charge of migrant inclusion and a person categorized as a migrant with precarious legal status share, when they meet face to face? They do not know each other and they have never met before, but a bond is assumed to be created between them. They find themselves in an unequal power relationship, since the institutional practitioner has the power to decide through their intervention on the fate of their interlocutor. What is left in this connection which is not direct or spontaneous, but rather mediated by protocols and paperwork, and in which each person already has an assigned role which he/she plays or contests? I tried to answer these questions in my Identities article, ‘Back in order’: the role of gatekeepers in erecting internal borders in Barcelona’, exposing the role of emotions in migrants’ control in urban space, what I understood as a bordering practice.

Migration enforcement is accompanied by emotions expressed by various actors – including the broader public, politicians and those targeted by practices such as deportation and detention – but also those of bureaucrats who implement policies. Emotions are addressed towards or expressed against a multitude of groups, such as asylum seekers or migrants with precarious legal status, as well as police officers and administrative and non-governmental staff.

Studying emotions directed at different groups uncovers, on the one hand, the intricate and complex network of actors working within the field of migration enforcement, both new and old. On the other hand, it presents the researcher with a density of relations that, as I argue in my Identities article, ‘Tracing the circularity of emotions in Swiss migration enforcement: organizational dissonances, emotional contradictions and frictions’, can be analyzed through a focus on emotions, thus advancing our understanding of statecraft and organizational construction.

When we speak of borders, we usually either refer to the lines considered to separate nation states or to the actions we are asked to perform when arriving in another country (such as showing one’s identity document or choosing a green or red lane depending on the goods we wish to declare). However, researchers working in the field of border studies have long started to think about borders in a much larger sense as spatial phenomena related to processes of inclusion and exclusion. Today’s global cities provide numerous examples of such phenomena. From gated communities to gendered spaces or neighbourhoods described as ‘ghettos’, cities often display spatial orders that limit the free movement of their inhabitants.

I was inspired to study French banlieues through the prism of critical border studies after a series of encounters with colleagues from the Alsatian city of Strasbourg. Like many of their fellow Strasbourgeois, these colleagues often went to the neighbouring German town of Kehl, where goods such as fuel, cigarettes or basic necessities from discount stores are considered cheaper. In normal times, this border is not policed and thousands of commuters, tourists and shoppers cross the Rhine every day. In contrast, none of my colleagues had ever gone to the Neuhof, a banlieue with a poor reputation in the southern suburbs of Strasbourg. At university, I met a Comorian-born student who lived in this area. He told me that the most difficult part of living in this socially vulnerable neighbourhood were not the living conditions as such, but the police controls and the regular frisking he experienced at least every week when taking the tram to the city center. For him, the true border did not run along the Rhine; it separated his neighbourhood from the rest of Strasbourg. |

|

Explore Identities at tandfonline.com/GIDE |

|

The views and opinions expressed on The Identities Blog are solely those of the original blog post authors, and not of the journal, Taylor & Francis Group or the University of Glasgow.