|

|

|

Blog post by Hamdullah Baycar, University of Exeter, UK

‘It kind of makes me feel like Batman or Superman. You can say the things you want to say with your own voice and your own style’, said Malcolm Bidali, a Kenyan security guard employed in Qatar, regarding his activism about labour conditions on social media. His activism led to his detention in 2021. The incident gained significant public attention, and 240 Qatar Foundation students, alums, faculty and staff signed a petition asking for his release.

Two days after the petition, even Qatar's state-owned media, Al Jazeera, was involved in the debate and ran with the headline, ‘Concerns over Qatar's arrest of a Kenyan security guard’. Thus, the digital sphere, which initially caused his detention, ultimately became the tool that freed him. Although Bidali's case cannot be considered representative of the entire Gulf region and is not directly related to the UAE, it does demonstrate the power of social media and the digital sphere, even in supposedly autocratic states.

0 Comments

Blog post by William Shankley, University of Nottingham, UK

Nearly twenty years have passed since the expansion of the European Union (EU) led to the significant movement of Polish citizens to the UK. Despite the UK's subsequent departure from the EU, Polish migration assumes a prominent place in the country's migrant diversity. Belonging is a crucial aspect of migrants' lived experience in another country, and previous studies on Polish migrant belonging in the UK have primarily focused on the neighbourhood context as this is contested, resisted and reshaped. Additionally, the majority of existing research has predominantly concentrated on Polish migrants' belonging among those working in low-skilled industries, which was the dominant occupational position most Polish migrants entered into. Nonetheless, Polish migrants' entry into a range of workplaces after their migration offers an equally important site in which to examine their belonging. Furthermore, there has also been a lack of research into Polish migrants working in professional occupations and their belonging at work.

Earlier this year, Home Secretary Suella Braverman announced she was not proceeding with multiple recommendations made by Wendy Williams’ public inquiry into the Windrush Scandal. The inquiry examined the Home Office’s adverse actions against people from the Windrush generation who predominantly migrated to Britain from the Caribbean between 1948 and 1973 (Gentleman 2019; Slaven 2022). Reports have detailed the profound effects on those directly impacted, revealing stories of individuals who were denied healthcare and welfare services, and in some cases were ripped away from their families; detained and even deported (Gentleman 2019; Williams 2020; Slaven 2022). The ensuing scandal thrust their treatment into the public consciousness and ignited a public uproar. Yet, as the scandal faded from media attention, we still have a limited understanding of the scandal’s broader impact on Britain's racialised communities, beyond those directly affected by the Home Office’s actions.

In 2018, the research department of Awel, a Flemish civil society organization, published a report on the impact of the late terrorist attacks in Europe on the identity formation of minority youth. The report, based on testimonials, revealed that some Muslim children try to hide their ethno-religious background out of fear of being verbally attacked. Some even wish to ‘unbecome’ Moroccan or Muslim to respond to Islamophobia.

The largest ethnic minority group in Belgium originates from Morocco. This primarily Muslim group is indeed strongly stigmatized, even more so since 9/11. It is argued that terrorist attacks increase Islamophobic or anti-Muslim sentiments, which hence also impacts the well-being of Muslim children living in Flanders. The findings of the research report nevertheless did not receive as much public and political attention as deserved. Yet, ethnic minority citizens’ identity formation has long been a subject of political interest, especially since many politicians across the spectrum propose that minorities, and particularly Muslims, do not identify as Belgian.

Migration enforcement is accompanied by emotions expressed by various actors – including the broader public, politicians and those targeted by practices such as deportation and detention – but also those of bureaucrats who implement policies. Emotions are addressed towards or expressed against a multitude of groups, such as asylum seekers or migrants with precarious legal status, as well as police officers and administrative and non-governmental staff.

Studying emotions directed at different groups uncovers, on the one hand, the intricate and complex network of actors working within the field of migration enforcement, both new and old. On the other hand, it presents the researcher with a density of relations that, as I argue in my Identities article, ‘Tracing the circularity of emotions in Swiss migration enforcement: organizational dissonances, emotional contradictions and frictions’, can be analyzed through a focus on emotions, thus advancing our understanding of statecraft and organizational construction.

When we speak of borders, we usually either refer to the lines considered to separate nation states or to the actions we are asked to perform when arriving in another country (such as showing one’s identity document or choosing a green or red lane depending on the goods we wish to declare). However, researchers working in the field of border studies have long started to think about borders in a much larger sense as spatial phenomena related to processes of inclusion and exclusion. Today’s global cities provide numerous examples of such phenomena. From gated communities to gendered spaces or neighbourhoods described as ‘ghettos’, cities often display spatial orders that limit the free movement of their inhabitants.

I was inspired to study French banlieues through the prism of critical border studies after a series of encounters with colleagues from the Alsatian city of Strasbourg. Like many of their fellow Strasbourgeois, these colleagues often went to the neighbouring German town of Kehl, where goods such as fuel, cigarettes or basic necessities from discount stores are considered cheaper. In normal times, this border is not policed and thousands of commuters, tourists and shoppers cross the Rhine every day. In contrast, none of my colleagues had ever gone to the Neuhof, a banlieue with a poor reputation in the southern suburbs of Strasbourg. At university, I met a Comorian-born student who lived in this area. He told me that the most difficult part of living in this socially vulnerable neighbourhood were not the living conditions as such, but the police controls and the regular frisking he experienced at least every week when taking the tram to the city center. For him, the true border did not run along the Rhine; it separated his neighbourhood from the rest of Strasbourg.

Experiences of displacement and longing-for-a-home are very much rooted in the human condition. In this discussion I consider three books focusing on displaced people of distinct diasporas whose experiences, I believe, provide novel insights into not only what exile may mean but how it may, in different ways, condense time and space into symbols, meanings, and narrations of religious, political, or material significance. These include Thomas A. Tweed who approaches the experience of exile of Cubans in Miami by deciphering the material culture inherent in their pilgrimage site and meanings embedded in their rituals while mainly asking how diasporic religion and exile experience may be connected. Sara E. Lewis, meanwhile, explores the exile experience of Tibetan Buddhists in Dharamsala, India by looking into the local processes of resilience and recovery in the face of political violence while asking how human rights campaigns and foreign trauma discourse are situated within a form of life shaped by Buddhist ideals of downplaying personal suffering. Finally, Diana Allan analyzes the experience of exile of Palestinians in Shatila refugee camp in Lebanon, drawing our attention to the everyday material reality of their experience while raising the question of what it means for generations born in exile to aspire for a liberated land which they never left and how these refugees may resist against purely nationalist identities and ideals.

Populist parties and leaders have become important actors across the globe. The 2022 presidential elections in France, and parliamentary elections in Sweden, as well as Turkey’s 2023 presidential elections not only revived academic research on populism and stirred scholarly debate about how to conceptualize it, but also compelled electors and political actors to reflect on the political developments taking place on the populist right front.

In our Identities article, ‘The veil as an object of right-wing populist politics: A comparative perspective of Turkey, Sweden, and France’, we selected three countries which have extremely different religious, secular, and cultural contexts. We then analyzed the political statements by the radical right-wing parties in each of the chosen countries: the Justice and Development Party (Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi, AKP) in Turkey, the National Rally (Rassamblement National, NR) in France and the Sweden Democrats (Sverigedemokraterna, SDs) in Sweden.

On the 14th June 2017, a horrific fire swept through Grenfell Tower in west London, killing 72 people and leaving hundreds more homeless and traumatised. For those of us who witnessed the tragedy unfold, either directly or through media coverage, the images of the burning tower beyond the control of the firefighters will stay with us for a lifetime.

Situated within the wealthy borough of Kensington and Chelsea, with a 71% white demographic, the 24-storey tower block was home to mainly social housing tenants of many ethnicities and backgrounds. Much has been written about how social marginalisation had created a hostile and dangerous environment for residents of the tower. In the years preceding the fire, they were treated as expendable against the forces of gentrification, de-regulation and cuts, and their voiced concerns about the loss of green areas and fire safety in Grenfell Tower were repeatedly ignored. In 2019, the Grenfell Tower Inquiry Report determined that the speed with which the fire spread was due to the combustibility of the substandard exterior cladding, an addition made largely to enhance the tower’s appearance to surrounding neighbourhoods.

In the aftermath of the 2016 attempted coup against the Erdoğan government in Turkey, several hundred Turkish-Dutch citizens took to the streets in the Netherlands. Some protesters harassed a journalist documenting the protests. Prime Minister Mark Rutte responded by telling the demonstrators to ‘piss off to Turkey’. This statement exemplifies how Turkish-Dutch citizens, born and raised in the Netherlands, can be scrutinised and quizzed about their loyalty and the extent of their integration. When they express deviant behaviour or political views in the eyes of the majority, they are considered ‘Turks’ or ‘Muslims’ only, which is not reconcilable with being ‘Dutch’. Politicians often understand Dutchness in a culturalised way, in which progressive ideals such as gender equality, sexual liberty and democracy are considered to be important signifiers of Dutchness. This frame creates a contrast between progressive ‘natives’ and ethnic minority citizens, who are othered as backwards, not sharing these progressive values.

How do Turkish-Dutch Muslim young adults deal with such stigmatisation? This is the question we raise in our Identities article, ‘Claiming the right to belong: de-stigmatisation strategies among Turkish-Dutch Muslims’. Investigating de-stigmatisation strategies by Turkish-Dutch youngsters contributes to understanding processes of belonging, social inequality and ethnic boundary-making. Stigmatised individuals can contest and rephrase their position, bringing about social change and upsetting existing social categories. To explore de-stigmatisation, we interviewed 25 Turkish-Dutch, Muslim young adults and conducted ethnographic observations in two youth groups.

Due to the accessibility of the internet and the ability of online spaces to bring people together, platforms like social media sites and web forums have allowed globally dispersed communities to engage in conversations about identity and belonging. For my Identities article, ‘Connectivity, contestation and cultural production: an analysis of Dominican online identity formation’, I collected and analysed text data from a web forum that I call ‘DRLive’ to show the kinds of identity discourses that happen online. This site caters to all things Dominican Republic, with free and open forum pages where Dominicans and non-Dominicans participate in discussions covering numerous topics. Adding to work on diaspora, migration, and cultural production among Dominicans, I propose forums and other virtual spaces as additional sites where diasporic and non-diasporic Dominicans come together to talk about and challenge evolving interpretations of identity, history and cultural memory.

Cultural memory, which is defined as a collection of commonly shared historical moments and experiences, is passed on and shared over time by members of a nation. In the case of this forum, for example, I find that ‘the contrived historical narratives propagated in the Dominican Republic throughout the 19th and 20th centuries continue to inform how Dominicans in the country and in the diaspora interpret and construct Dominicanidad.’ Work on virtual spaces often seeks to address how migration might affect the maintenance of cultural memory, especially as second- and third-generation immigrant communities emerge far from their homeland.

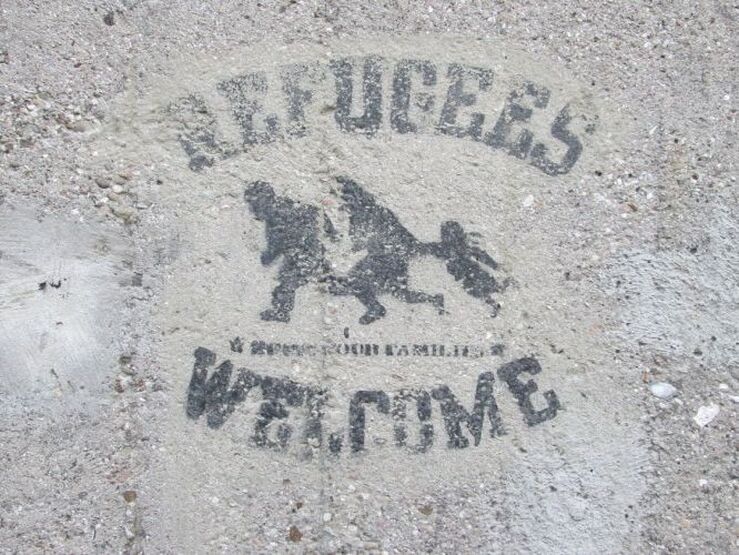

Since 2015, several European countries have witnessed an unprecedented involvement of citizens in forms of refugee support which have been gradually identified in public discourse as a newly emerging ‘culture of welcome’. While acts of solidarity are not a new phenomenon, these emerging mobilisations, often enacted by people with no activist background, hint at an inherent tension between the official stance on the ‘refugee crisis’ and the grassroots responses to it.

The experiences of ordinary people hosting refugees in their homes, often with the intermediary role either of NGOs or of local authorities, shows that no matter how micro or widespread, these emerging housing arrangements make for a ‘social lab’ in which broader societal issues can be fruitfully revisited. Interestingly, refugee hospitality initiatives relocate forms of pro-refugee support from the public arena into the intimate space of the domestic. In doing so, they shed light on emerging practices of ‘domestic humanitarianism’, understood not just as an impulse to offer care tied to specific notions of ‘responsible citizen’, but as a mode of helping that takes place inside the home. At the same time, they evoke the contentious reconfiguration of the mainstream views and boundaries of home – who is entitled to belong in a place and call it home – at the domestic, community and national levels.

Arab Americans have been categorised as White on official government forms for several decades, which grossly misrepresents this population. Advocacy groups unsuccessfully fought during both the Obama and Trump administrations to have the ethnicity category expanded in the 2020 Census. The ramifications of this community remaining uncounted include lack of funding for social, education, and health care services and less leverage in political issues. Along with negating the incredible diversity within this group, such categorisation excludes Arab Americans from affirmative action programmes.

The recognition of this ethnic group on government forms would allow for their inclusion in such programmes, which is crucial given the prominence of discrimination in the US. However, the irony lies in how mainstream society tends to change their view depending on current events. When there are no crises involving Arabs around the world, Arab Americans are seen as White. However, when a crisis does occur involving Arabs – as either transgressors or victims (i.e. 9/11, invasion of Iraq) – they will be gazed upon as ‘Other’ and enemies of America. The rise in hate crimes against Arab Americans – and anyone who fit into the public’s notions of what an Arab or Muslim looks like – following the terrorist attacks of 9/11 is a prime example of this phenomenon. Consequently, regardless of being labeled as White, Arab Americans have experienced discrimination similar to other racially visible minority groups. This begs the question: if they are recognised as White, then why are they treated as ‘Other’?

The recent visit by Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi to Bangladesh to attend celebrations marking 50 years since the birth of the country following the Liberation War in 1971 has drawn attention to the difficult task of building a nation on the back of a brutal and bloody civil war. At least four people were killed by police in the Bangladeshi city of Chittagong during a demonstration against Modi’s visit. Protesters from Hefazat-e-Islam Bangladesh, and counter protestors aligned with Bangladesh’s governing Awami League party, represent the central divide in Bangladeshi politics, between those who tie national identity to Islam and those who tie national identity to ethnicity and the Bengali language. This is a divide sometimes understood as one between those who ‘collaborated’ with the Pakistani military and those who participated in the independence struggle. On the Golden Jubilee of Bangladesh’s birth, this divide continues to shape Bangladesh’s political landscape today.

Using the case of the ‘Urdu-speaking minority’ in Bangladesh, my Identities article, ‘Displacement, integration and identity in the postcolonial world’, considered what the experience of minorities displaced during the Liberation War tells us about the Bangladeshi national imagination today. Their own voices, and the narratives of identity and integration in which they are situated, are revealing of the nature and boundaries of the nation state fifty years on from the country’s birth. Although the country remains divided around the role or significance of religion versus culture, and between those who ‘collaborated’ with the Pakistani military and those who participated in the independence struggle, there are older divides at work here too. Some of those who ended up on the wrong side of the Liberation War are accepted into the nation today. Here colonial narratives of ‘population’ versus ‘people-nation’, ‘community’ versus ‘citizen’ structure exclusion not only through narratives of the country’s foundation myth (as commonly assumed) but also through poverty and social space.

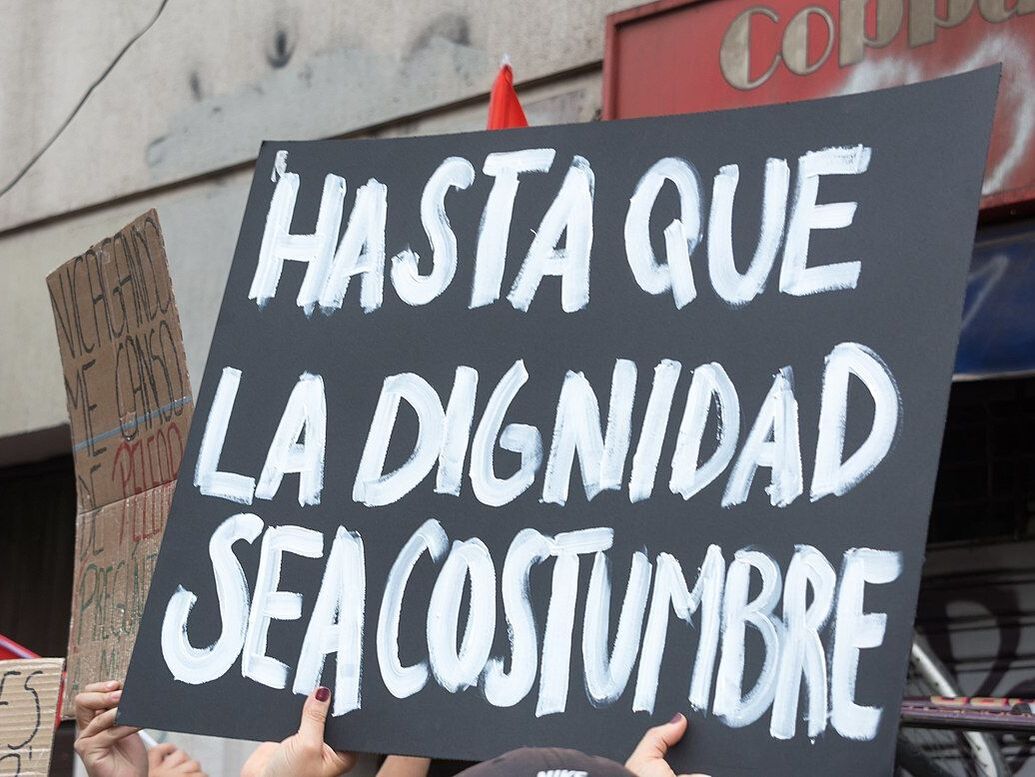

While writing our Identities article, ‘Disjunctive belongings and the utopia of intimacy: violence, love and friendship among poor urban youth in neoliberal Chile’, we had already started to witness a series of protests that recently culminated in the so-called Chilean ‘social outburst’ in October 2019 and the current process building a constituent assembly. Issues of quality of education, environmental concerns, shortcomings in the social security system, as well as long-standing efforts for the cultural and political recognition of indigenous groups gained increasing support over time. Yet, the many protests still appeared geographically scattered, and while people in the urban margins indeed felt uneasy with their life prospects, it was still uncommon to hear people articulate a more thorough critique of the neoliberal model that has prevailed in Chile for the past forty years.

In Los Acantos, the residents we met in 2012–2013 were conscious of these issues. Many of the young residents we met saw no way out in a world bounded off by invisible borders of social (in)difference and stigma. People were, in other words, aware of their almost impossible odds of socio-economic mobility and underneath the surface of monotonous low-income houses, the attentive ethnographer could feel the discontent.

Becoming an adult is a momentous experience in the lives of young people. This period comes with a variety of exciting new responsibilities and an overall shift in one’s sense of identity within their communities. In recent times, scholars have indicated that increasingly, young people are understanding adulthood based on self-ascribed character traits and values, as opposed to external societal milestones. Yet, this process can be influenced by culture and context. For example, in certain ‘Western’ contexts, for some youth from migrant and refugee communities, this process of becoming an adult can be a complex negotiation of cultural norms, as they are both (a) making sense of their cultural identity in a new home country and (b) making sense of their cultural identity as young adults.

In our Identities article, ‘Eighteen just makes you a person with certain privileges’: the perspectives of Australian Sudanese and South Sudanese youths regarding the transition to adulthood’, we set out to better understand Australian Sudanese/South Sudanese youths’ views on becoming adults. The timing of our study was pertinent, because during this time these young people were receiving intense public and political attention in the media, which questioned their overall belonging in Australia. These media representations were in response to criminal events, allegedly involving youth from these communities, and were heavily racialised, framing these young people as dangerous ‘outsiders’.

The illusion of Britain as a post-racial society, or at least a multi-cultural society at ease with racial mixing and mixedness that the royal wedding of Prince Harry and Meghan Markle conjured up, has been wiped aside by the couple’s revelation of the racism they had faced within the royal family, including questioning about the potential skin colour of their first born. Britain may have around one in ten of couples in a mixed relationship, but clearly this does not signal antiracist progress. Meghan will have dealt with overt and covert racism all her life, but it must have been a steep learning curve for Harry. What will this mean for how he seeks to bring up his son and soon-to-be born daughter?

In my Identities article, ‘Partnered fathers bringing up their mixed-/multi-race children: an exploratory comparison of racial projects in Britain and New Zealand’, I took an in-depth look at how fathers of mixed-race children sought to equip them to deal with racism, and give their children a sense of identity and belonging. Drawing on racial formation theory, I explored the individual racial projects that they pursued for their children, interacting with historical, social and political nation state racial projects.

Undocumented youth, or those young people living in the United States without legal immigration status, encounter significant challenges at important moments in their life, such as looking for their first part-time job or securing a driver’s licence. When they apply for college, they find they are ineligible for many scholarships and all forms of federal financial aid. For many scholars, these significant challenges mean that being undocumented functions as a ‘master status’ – a key aspect of their identity that has a marked influence on their life experiences. Scholars such as Roberto Gonzales argue that for some undocumented youth, ‘learning to be illegal’ is synonymous with experiences of exclusion during the transition to adulthood.

Although legal status certainly shapes undocumented youths’ experiences in applying to and attending college, Laura Enriquez reminds us that other aspects of undocumented students’ identity, such as race or class, also play a significant role in persistent inequalities that shape undocumented college students’ experiences – particularly those feelings of not belonging on a college campus. Enriquez shows that being poor and a first-generation college student influences undocumented students’ likelihood of stopping out of school both earlier in the life course and to greater effect than legal status does. Consequently, she concludes that undocumented status does not function as a master status, but rather, serves as a ‘final straw’ that imparts feelings of not belonging rooted in exclusionary experiences, which tip the scale in the direction of withdrawing or dropping out of college. Her research questions whether undocumented status acts as a master status at all, choosing instead to underscore its affective and relational influence when combined with other master status identities such as race or class.

The places in which people contest and negotiate cultural diversity are themselves meaningful. Places hold cultures, histories and memories, and shape people’s interactions. A suburb of a city is one such place.

In our Identities article, ‘Making a place in Footscray: everyday multiculturalism, ethnic hubs and segmented geography’, we explore the meaning and experiences of cultural diversity in Footscray, a suburb of Melbourne, Australia. We interviewed both residents of Footscray and others who had close connections to the suburb about their everyday experiences in the suburb, particularly around cultural diversity. Footscray is culturally diverse, both in terms of the number of people born outside of Australia and the range of nations from which people have migrated. While racism and racialisation form part of the dynamics of the suburb, Footscray, on the whole, is a place in which people embrace cultural diversity, and everyday diversity has come to be a defining feature of the suburb.

As the COVID-19 pandemic rendered people around the world homebound, home for some US citizens turned out to be the colonial town of Granada, along the shores of Central America’s largest lake, Lake Nicaragua, in a country many of these settlers had known only as the bloody battleground of the revolutionary Sandinistas and the counter-revolutionary (US-Backed) Contras.

These ‘expats’ began migrating to Nicaragua, in earnest, in the early 2000s (though an American presence in the country extends much further back in history). They are drawn by a quest for adventure, but also by affordable, spacious Colonial-era homes, maids and gardeners, and upscale restaurants in a country ranked second poorest in Latin America. In stark contrast to the attention focused on ‘caravans’ of migrants fleeing Central America en route to the US, these US citizens and other north-south migrants go generally unnoticed in the public discourse on global migration. My Identities article, ‘Rooted in relative privilege: US ‘expats’ in Granada, Nicaragua’, examines this group of international migrants, incorporating some of the same concepts used to study their counterparts moving from the Global South to the Global North. Based on fieldwork in Granada, Nicaragua and in-depth interviews with 30 US citizens who have made their homes there, I focus on how these individuals negotiate a sense of identity and belonging as US citizens residing full-time in Nicaragua.

In the 1950s, the world famous American-born entertainer Josephine Baker, who lived in France, toured the US. She was refused in 36 hotels in New York because she was black.

Back in France, Baker adopted twelve children from 10 different countries in order to prove to the world that people of all ‘races’ and religions could live together. She organised tours through the castle where she lived with her ‘rainbow tribe’ and made the children sing and dance. In the 1920s and 1930s the popular novelist Pearl S. Buck adopted seven children, four of whom were labelled ‘mixed-race’. By doing so she flaunted American restrictions on mixed-race adoptions. In the 1950s, Buck said she did so because she wanted to show that families formed by love – devoid of prejudices based on race, religion, nation, and blood – were expressions of democracy that could counteract communist charges that America’s global defence of freedom was deeply hypocritical. The adoptions by Baker and Buck were political statements that illustrate that intercountry adoptions were frequently about much more than saving a child, as many people who defended adoptions claim. My Identities article, ‘Parenting, citizenship and belonging in Dutch adoption debates 1900-1995’, explains why debates on this issue continued, without ever reaching a conclusion. Celebrities (including Madonna, Angelina Jolie and Brad Pitt) followed in the footsteps of Baker and Buck. Non-celebrities copied behaviour and arguments. Adopters tried to show that children and adults not connected by blood ties could form a family, and that single parent adoptions or adoption by same sex couples could work. Critics pointed to child kidnappings, trafficking, ‘baby farms’ and a profit-driven industry based on global inequality. Adoption was not a solution to poverty, nor in the best interest of the child, in their view.

When migrants move abroad and start their life in a different location, they may keep their loyalties and links to their place of origin and combine them with newly built connections to their new location. Such transnationalism, though it is a well-known phenomenon, is perceived as problematic from the state point of view as it is difficult to predict the loyalty of such migrants (if they are loyal to their new state or the state of origin).

However, it also brings many dilemmas for individual migrants. One of these dilemmas is how to answer to question, 'who am I'. New identities developed in a new place need to be combined with existing ones. This is extremely difficult in the case of national identities which are built on an opposition of ‘us’ and ‘them’. If I define myself as a member of particular nation in opposition to other nations, how do I develop a new identity related to a foreign land where a foreign national lives? How do I solve a conflict of loyalties between my old and new national identity? My Identities article, 'Game of labels: identification of highly skilled migrants', calls the process of building new hybrid identities ‘a game of labels’.

For some migrant farm workers, exiting their state-approved contracts can provide an everyday means to refuse poor working conditions and evade coercive immigration and employment controls that are endemic to the agricultural streams of Canada’s Temporary Foreign Worker Program. Exiting their employment, an action that workers refer to as ‘escape’, puts at risk their right to legally reside in Canada.

However, in my Identities article, '"Escaping" managed labour migration: worker exit as precarious migrant agency', I examine how workers’ first-hand depictions of ‘escaping’ employment reveal new insights into how workers may claim a space of belonging that contradicts their experiences of status-based vulnerability. By leaving the farm and by extension Canada’s state-managed labour migration regime, workers are both refusing a life of precarity and embracing an unknown future where hope and chance may reveal a happier and more desirable life.

When you see images of French daily life or French people in magazines, films, or other media, what do you see?

Usually, it’s white people, with perhaps a few visibly non-white people depicted. But this is odd for multiple reasons. One, France has a long history of immigration, primarily from its overseas territories and former colonies. Due to years of colonialism, colonial slavery, and subsequent migration, ethnic minorities, or 'visible minorities' in French academic parlance, have long been part of French society. Secondly, France does not acknowledge or measure race as a separate identity category. So while France is a multicultural society, it does not, as a facet of law, distinguish between these different cultures. One is either French or not. This is France’s Republican model. |

|

Explore Identities at tandfonline.com/GIDE |

|

The views and opinions expressed on The Identities Blog are solely those of the original blog post authors, and not of the journal, Taylor & Francis Group or the University of Glasgow.