|

|

|

As the COVID-19 pandemic rendered people around the world homebound, home for some US citizens turned out to be the colonial town of Granada, along the shores of Central America’s largest lake, Lake Nicaragua, in a country many of these settlers had known only as the bloody battleground of the revolutionary Sandinistas and the counter-revolutionary (US-Backed) Contras.

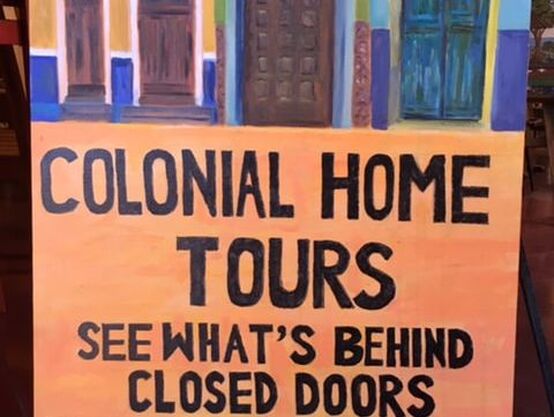

These ‘expats’ began migrating to Nicaragua, in earnest, in the early 2000s (though an American presence in the country extends much further back in history). They are drawn by a quest for adventure, but also by affordable, spacious Colonial-era homes, maids and gardeners, and upscale restaurants in a country ranked second poorest in Latin America. In stark contrast to the attention focused on ‘caravans’ of migrants fleeing Central America en route to the US, these US citizens and other north-south migrants go generally unnoticed in the public discourse on global migration. My Identities article, ‘Rooted in relative privilege: US ‘expats’ in Granada, Nicaragua’, examines this group of international migrants, incorporating some of the same concepts used to study their counterparts moving from the Global South to the Global North. Based on fieldwork in Granada, Nicaragua and in-depth interviews with 30 US citizens who have made their homes there, I focus on how these individuals negotiate a sense of identity and belonging as US citizens residing full-time in Nicaragua.

When asked about their primary identification, the majority of respondents (22 of 30) replied with: ‘American’. They described maintaining close social, emotional and cultural ties to the US – more so than political ties. At the same time, they also shared feelings of attachment and identification with their adopted land. This attachment was primarily to the town where they were making their homes, Granada, and to fellow ‘expats’ with whom they were forming community. But it extended as well to local ‘Nicas’ who they were being served by in restaurants, bars, markets and in their homes as hired maids, cooks and gardeners, or who they were serving through charitable organisations dedicated to providing assistance to the host community in areas of education, medical care and other social services. It was not unusual for US migrants to use the pronoun ‘we’ simultaneously in reference to Granada, or Nicaragua, and in reference to Americans, or the US.

In many ways, these US citizens living in Nicaragua fit the model of ‘transmigrants’ introduced by sociologists in the early 1990s, to describe those who ‘take actions, make decisions, and develop subjectivities and identities embedded in networks of relationships that connect them simultaneously to two or more nation-states’ (Basch, Glick-Schiller & Blanc 1994, 3). An even closer fit comes from a revised analysis of transnationalism in 2004, which emphasises the predominance of ‘bi-localism’, or trans-state connections between particular places, here and there (Waldinger & Fitzgerald 2004, 1182). While familiar concepts in the study of international migration shed light on the transnational mobility of privileged migrants too, the practices of this less familiar group also help us to refine existing concepts. Given that transnationalism has been largely theorised on the basis of, and applied to, migrants leaving less affluent countries for more affluent ones, case studies of the reverse migratory trend are instructive. Border crossing as a mechanism for navigating the vagaries of 21-century globalisation is becoming more widespread, but the degree of economic, political and cultural privilege of the trans-migrants fundamentally shapes the nature of the transnational ties they form and maintain. References: Basch, L., Glick Schiller, N. & Szanton Blanc, C. 1994. Nations unbound: transnational projects, postcolonial predicaments, and deterritorialized nation states. Langhorne, PA: Gordon and Breach. Waldinger, R. & Fitzgerald, D. 2004. Transnationalism in question. American Journal of Sociology 109 (5): 1177–1195.

Blog post by Sheila Croucher, Miami University, USA

Read the full article: Croucher, Sheila. Rooted in relative privilege: US ‘expats’ in Granada, Nicaragua. Identities: Global Studies in Culture and Power. DOI: 10.1080/1070289X.2016.1260022

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

|

Explore Identities at tandfonline.com/GIDE |

|

The views and opinions expressed on The Identities Blog are solely those of the original blog post authors, and not of the journal, Taylor & Francis Group or the University of Glasgow.