|

|

|

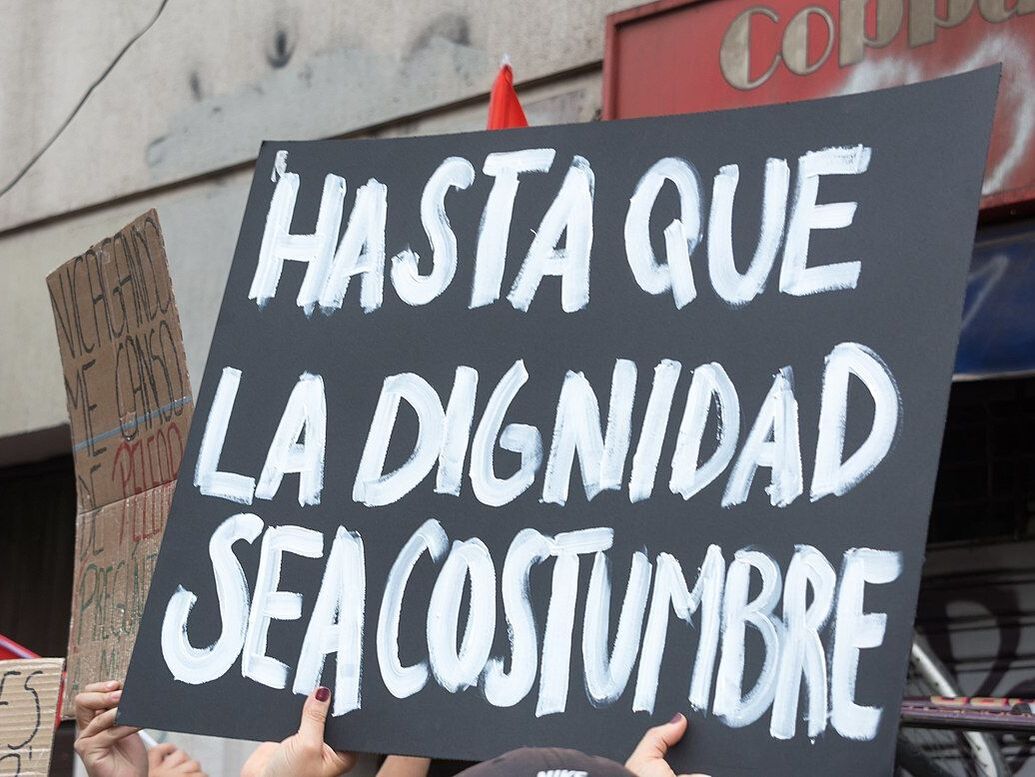

While writing our Identities article, ‘Disjunctive belongings and the utopia of intimacy: violence, love and friendship among poor urban youth in neoliberal Chile’, we had already started to witness a series of protests that recently culminated in the so-called Chilean ‘social outburst’ in October 2019 and the current process building a constituent assembly. Issues of quality of education, environmental concerns, shortcomings in the social security system, as well as long-standing efforts for the cultural and political recognition of indigenous groups gained increasing support over time. Yet, the many protests still appeared geographically scattered, and while people in the urban margins indeed felt uneasy with their life prospects, it was still uncommon to hear people articulate a more thorough critique of the neoliberal model that has prevailed in Chile for the past forty years.

In Los Acantos, the residents we met in 2012–2013 were conscious of these issues. Many of the young residents we met saw no way out in a world bounded off by invisible borders of social (in)difference and stigma. People were, in other words, aware of their almost impossible odds of socio-economic mobility and underneath the surface of monotonous low-income houses, the attentive ethnographer could feel the discontent.

0 Comments

The 21st century has witnessed a range of mass movements and street protests around the Arab world. In early 2011, an uprising founded on visions for a more just and free Egypt led to the overthrow of President Hosni Mubarak, while the following years and the election of Field Marshall Abdel Fattah al-Sisi proved that the military regime was far from defeated. Nevertheless, both opposition protests and state arrests continue to influence politics and everyday life in the country. For young people, political events are often formative for their images of what the future holds and what possible selves they imagine. The contemporary context of Egypt thus provides an opportunity to analytically explore the dynamics and intertwinement of personal hopes, utopian aspirations and post-revolutionary nostalgia and disappointment.

In my Identities article, ‘Experimenting with alternative futures in Cairo: young Muslim volunteers between god and the nation’, I examine how the personal hopes of young middle-class Egyptians develop into utopian aspirations for an alternative society, and eventually, how such aspirations are both strengthened and shattered in the aftermath of an uprising. Through ethnographic fieldwork among volunteers in Resala, Egypt’s largest Muslim youth NGO, from 2009 to 2015, I followed some of these young people from their first experiences with Muslim volunteer work through their excitement of the 2011 uprising. and finally to post-revolutionary times where they again renegotiate their orientations towards the future.

Eating took central stage in my research a few months in to my year of fieldwork in a Rio de Janeiro favela. Favelas are complex social areas, wherein the history of colonisation and slavery intersect with the present of extreme socio-economic inequality. There also exist the violence of the drug trade, and of highly controversial policing programmes. So you may ask: of all the things to speak of, why eating? Eating is a method, enabling pathways for the self to grow, and to become.

In my Identities article, ‘Eating bodies, growing selves in a Brazilian favela’, I argue that eating can be used as an active attempt at asserting agency over one’s body and, by extension, subjectivity in a lifeworld open to multiple dimensions of uncertainty and insecurity. Nonetheless, my interlocutors’ relationship to food and eating could also be ambivalent. Eating can pose constraints on subjectivity, and set the stage for the unfolding of problematic kin, gender and post-colonial relationships.

'They can either free us or finish us, once and for all!' an elderly woman told me in 2015 at a small protest gathering in Srinagar, the capital of Indian-controlled Kashmir. The woman had joined her neighbours at a local district official’s office to demand the removal of a military bunker from their neighbourhood. For the previous twenty-five years, the bunker had been a threatening presence in their neighbourhood. The soldiers stationed inside monitored public movement closely and violently enforced the ever-shifting rules of mobility, especially during curfews, when government arbitrarily closed down entire towns and cities. The soldiers didn’t hesitate to beat up, detain or even shoot at civilians seen out walking on the streets during curfews.

The Kashmiri protestors knew well that the local official they were meeting with their appeal had no power to remove the bunker. But there was nowhere else to protest, for those who possessed real power and made decisions that profoundly affected the lives of ordinary Kashmiris — the higher echelons of the Indian political, bureaucratic and military establishment — were furthest from these everyday sites of anxiety and fear in Kashmir. Since 1990, when Indian military were given emergency powers in the region to curb the popular pro-independence movement, Kashmir had come to resemble an occupied zone. The woman’s words reflected a deep sense of claustrophobia felt by many Kashmiris, especially the youth, who have seen public spaces in the region being taken over by the Indian forces. |

|

Explore Identities at tandfonline.com/GIDE |

|

The views and opinions expressed on The Identities Blog are solely those of the original blog post authors, and not of the journal, Taylor & Francis Group or the University of Glasgow.