|

|

|

Earlier this year, Home Secretary Suella Braverman announced she was not proceeding with multiple recommendations made by Wendy Williams’ public inquiry into the Windrush Scandal. The inquiry examined the Home Office’s adverse actions against people from the Windrush generation who predominantly migrated to Britain from the Caribbean between 1948 and 1973 (Gentleman 2019; Slaven 2022). Reports have detailed the profound effects on those directly impacted, revealing stories of individuals who were denied healthcare and welfare services, and in some cases were ripped away from their families; detained and even deported (Gentleman 2019; Williams 2020; Slaven 2022). The ensuing scandal thrust their treatment into the public consciousness and ignited a public uproar. Yet, as the scandal faded from media attention, we still have a limited understanding of the scandal’s broader impact on Britain's racialised communities, beyond those directly affected by the Home Office’s actions.

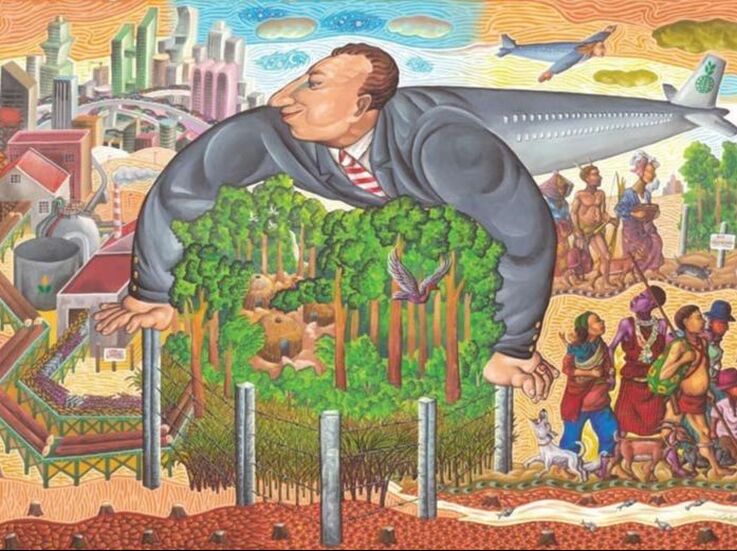

Discussions of contemporary white supremacy are seemingly everywhere: the election of Donald Trump and the January 6th insurrection, the murder of George Floyd, Brexit, the rise of the Alternative Right and white supremacist violence, and the coordinated efforts to deny racism and not educate children about the history and contemporary reality of race. These loud and important flashpoints, however, can unintentionally obscure the wider function and embodiment of white supremacy. That it is global and interconnected, is about systems and structures of power and not individuals, often hides in plain sight, and does not need ‘white’ bodies to sustain its power and replication.

For over a decade I have travelled to collect field data on race, globalization, development and labour in different Global South geographies. Through these engagements similar patterns became clear: countries in the Global South were beholden to policies dictated by the Global North. National groups racialized as white, or that exhibited a proximity to whiteness, were typically in positions of political and economic power. Those racialized as Black, or represented a distance from whiteness, had the worst material conditions. These seemingly very apparent global racial inequalities were often understood, though, as not about racism but about economic development, skills, capabilities, culture – essentially, anything but race.

Cross-posted from RACE.ED

As part of my final year at university, I completed research for my undergraduate dissertation, with a focus on the racial disparities within experience and attainment in higher education institutions. Bunce et al (2019) found that whilst 78% of white students are likely to receive a ‘good degree’ (2:1 or higher) only 66% of Asian students and 52% of Black students would reach the same classification, emphasising the hidden barriers for Black students. It was obvious that there was an invisible burden that many of the Black students I spoke to felt responsible to bear. One student described it as being the “Martin Luther King of the classroom”, the constant requirement to correct racism that goes ignored by those who are not Black. Another student further reinforced this point by describing how she felt that “…they are happy to ask the Black student what they should do but I think if it was other people’s problems, they would hire someone to find a solution…” These behaviours are not confined to the classrooms at universities but it is clear that these flippant expressions of racism are entrenched in practically every institution within the UK. For example, Parsons (2009) argues that policy is reactive rather than preventative; something has to occur before any form of retrospection is ensued by the institutions involved. The racist murder of Stephen Lawrence and the Macpherson report only confirmed the beliefs of many Black British citizens already.

The murder of George Floyd in the spring of 2020 sparked an outcry against police brutality and racial injustice in the United States. In the wake of the killing, support for the Black Lives Matter movement rose sharply among white Americans. Shows of support ranged from the (controversial) posting of blacked-out photos on Facebook and Instagram, to patronage of black-owned businesses, to marching in BLM protests.

We are now more than a year out from George Floyd’s killing. Much of the antiracist fervour expressed by progressive white Americans in 2020 appears to have fizzled. According to a Politico/Morning Consult poll, the percentage of white Americans with positive evaluations of the Black Lives Matter movement has declined significantly since last summer. Some see this change as an indication of the superficiality of many white Americans’ involvement in antiracism. While this may be true, our Identities article, 'Racemaking in New Orleans: racial boundary construction among ideologically diverse college students', points to the important role of racial boundary construction in limiting white Americans’ involvement in antiracist efforts.

In majority white countries, the Black Lives Matter protests that unfolded after the murder of George Floyd were accompanied by the intensification of public debates on systemic racism and white allyship. Some media focused on Black-white couples, discussing the impact of these events on white partners’ understanding of anti-black racism in their Black partners’ lives. As part of the ERC-funded project ‘Regulating Mixed Intimacies in Europe (EUROMIX), over the past four years I have explored Black-white couples’ experiences of racism and discrimination in their everyday lives.

Drawing from ethnographic fieldwork I conducted in 2018-2019, my Identities article, ‘Interracial couples and the phenomenology of race, place and space in contemporary England’, looks at partners’ perceptions of dis/comfort and un/safety across different contexts: when they jointly move in public spaces, choose where to make home, and travel for leisure. By juxtaposing these scenes, the article foregrounds a multi-layered economy of constraint and choice underpinning the lives of the opposite and same-sex couples that I have met and/or interviewed.

While never entirely going away, the relationship between football fandom and racism has over the past few months come into renewed focus. In a UK context, this concerns the continued controversy over players choosing to ‘take the knee’ before professional matches in protest of racial injustice, as well as online abuse targeting the three black players who missed penalties in this summer’s final of the Euro 2020 tournament. Against a back story of overt racism in English stadia throughout the 1970s and 1980s, these episodes remind us of the need to keep interrogating the use of racist language across English football.

In this context Millwall FC holds a somewhat unique, although unwanted, position. It is a club that is widely recognised – for its association with racist hooliganism – even among those who know little about football. This reputation dates back to the 1970s. Therefore, the idea of the black Millwall fan – as a category and an identity – causes raised eyebrows, as it appears an oxymoron that goes against existing perceptions of what constitutes a Millwall fan. It is the oral histories of black Millwall fans and players that are at the core of the Millwall's Changing Communities Research Project, funded by the Lottery and led by the South London-based charity Bede House.

Following George Floyd's horrific death and the scenes of his sensational courtroom trial which played out to public scrutiny across the world, my recently published Identities article, 'The dying Black body in repeat mode: the Black 'horrific' on a loop', addresses the notion of the recurrence of 'Black death' in repeat mode offline and its viral circulation online in the digital economy.

Digital platforms abstract dead bodies as floating matter to be consumed without context. In tandem, this 'repeat mode' produces a visuality or a 'shadow archive' to showcase Black bodies as perpetually given over to brutality, violence and foreshadowed by the possibility and actuality of constant death. The horrific killings of Blacks is sustained through police brutality against the historic context of slavery, White oppression, segregation, Black civil rights movements and an American dream forged through Black death as part of a visual regime. My article opens up with the question from a Black student posted on a research mailing list online, on the troubling phenomenon of consuming Black bodies in demise in repeat mode on the internet. The student's query bridges a number of issues including the role of the digital sphere as a virtual graveyard in shaping Black consciousness and communion, given the internet's 'body snatching' tendencies in which violence, death and bodies struggling to 'breathe' float infinitum.

Cross-posted from The Conversation.

On BBC Sport, Match of the Day pundits Ian Wright and Alan Shearer recently had a conversation about racism in football. Shearer, the white ex-England international striker asked his black ex-teammate Wright: “Do you believe a black guy gets treated differently to a white guy?” Wright’s response was unequivocal: “Without a doubt, Al!” Black players face discrimination on every level: public (anti-black racism from fans in stadiums), private (abusive DMs on social media) and institutional (lack of management and coaching opportunities). Wright, however, also pointed to the disparate treatment players receive in the press, referencing recent reports on similar property investments by strikers Marcus Rashford and Phil Foden. Rashford, who plays for Manchester United and is black, was framed an extravagant, cash-rich, cash-loose footballer. Foden, meanwhile, who plays for City and is white, was described as the local Stockport boy looking after his family.

Cross-posted from Spectre.

'For us who are determined to break the back of colonialism, our historic mission is to authorize every revolt, every desperate act, and every attack aborted or drowned in blood.' – Frantz Fanon, The Wretched of the Earth [1] On July 19, 2016, Adama Traore, a 24-year-old Black construction worker, was killed after an arrest by three police officers in Beaumont-sur-Oise, a northern banlieue, or suburban outskirt, of Paris. Adama was stopped for an identity check — a not uncommon measure by which police officers stop individuals and ask for their identification (often disproportionately targeting Black and Arab individuals). In this case, Adama was taken to a nearby police station and by the time he arrived, he was dead. The police originally stated that he had died of a heart attack, and then said he had prior health conditions which caused his death. In late May, the three police officers were cleared in their involvement for Adama’s death.

Ken Carter, whose character inspired the realisation of the inspirational 2005 basketball movie, Coach Carter, decided to end the 1999 undefeated streak of Richmond High School basketball team because of his players' poor academic performance. His decision to lock the school gym and cancel the upcoming basketball matches, despite opposition amongst the Richmond community, garnered enormous US media attention framing it as an elevation of education over sports. While extensively elaborating and rationalising the gym shut-down in front of his students, Coach Carter posed a rhetorical question that resonates amongst recent events of police brutality and racial injustice in the US: where do these students end up after graduating high school? The answer for those who do not make it to college or into a professional sports career is, for many, probably prison.

Even though the US imprisonment rates have recently experienced its most significant decline in the last two decades, the Bureau of Justice Statistics (2018) data indicate that the US prison population's racial and ethnic makeup remains highly disproportionate to the actual demographics in the country. According to the US Justice Department, black Americans represent 33% of the sentenced prison population – a number nearly triple the 12% share of their US adult population. Even though the racial margin of incarceration has been in decline, black Americans constitute two times the rate of imprisoned Hispanics and slightly above five times the rate of imprisoned whites in the United States.

The recent Black Lives Matters (BLM) protests offer a juncture for Britain to have a broad and sensible conversation on race and racism, similar to that headed by the Clinton administration in America 20 years ago. The recent re-appearance of the debate on terminology – the question of how to refer to racialised groups in Britain – may be the beginning of this. It is not a new question but is being posed by a new generation of Black Britons, who having been born in the UK should be unfamiliar with Hall’s sense of living ‘on the hinge between the colonial and post-colonial worlds’ (Hall & Schwarz 2017, 11).

In my Identities article, ‘The stigma of being Black in Britain’, I argued that despite more than 50 years since Britain adopted its first Race Relations Act (1965), colour remains a ‘visible feature of the urban landscape’ (Hall & Schwarz 2017, 184) in the UK. I described Brexit as an indication that, as Stuart Hall wrote many years ago, many of the ‘white underprivileged…believe that what they experienced was not because they were poor and exploited but ‘because the blacks are here' (Hall & Schwarz 2017, 185).

The themes of becoming and opposition as identification resonated with me, a white man from the US, as I searched for alliance strategies of anti-racism and anti-essentialism in historically the most creolised part of Europe: Portugal, and more specifically, the capital city of Lisbon.

I had spent the better part of the late 1990s and early 2000s with hip-hoppers, mostly young men of African-Indigenous descent, in the working-class neighbourhoods on the outskirts of São Paulo, Brazil, and considered myself relatively prepared to approach the former metropole of Lisbon as a 'Black' city. During research stints from 2007 to 2013, I realised that the spatial dimensions and historical depth of Blackness were much more complex than I originally had appreciated. In particular, local creole-speaking rappers in Lisbon, Portugal, who identify as Cape Verdean, sometimes Portuguese, sometimes African, occasionally European or even American, tuned me into the predicament and potential empowerment of Blackness: Black time depends on Black space; Blackness as encounter. Understanding racial capitalism in Africa: a study of the Nigerian oil-dependent capitalist economy21/10/2020

My Identities article, ‘The capital, state and the production of differentiated social value in Nigeria’, problematises the Nigerian oil-dependent capitalist economy through the perspective of the Black radical tradition. Using Cedric Robinson’s concept of race, I analyse the racialism inherent in the Nigerian capitalist economic relations and the accompanying contradictions. Capitalism is a very powerful historical force that has influenced and still influences diverse social, political and economic landscapes. The state is an agency through which the association of individuals are entrusted with the administration of the affairs of a given society. Both the capital and state are essential agencies in the entrepreneurial model of the capitalist mode of production.

Marxist scholars present capitalism as an unfair system that engages in unequal distribution of the social wealth generated by the society. Marx argues that the capitalist society is divided along class line and the economic factor remains the most decisive determining factor in shaping capitalist dynamics and its contradictions, while culture and other human pre-occupations play a role but not the decisive one. The working class, Marx maintains, is the revolutionary class that will eventually transform the capitalist economy. Handsworth and the production of knowledge: Blackness, racism and anti-imperialism in 1970s Britain27/11/2019

The African Caribbean Self-Help Organisation (ACSHO), based at Heathfield Road in Handsworth, Birmingham, established itself as a central hub for Pan-African centred learning and intellectual debate in the early 1970s. ACSHO members were part of a UK-wide co-ordinating committee that sent a delegation of activists to the 6th Pan African Congress (6PAC) in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania in 1974. My Identities article, ‘Each one teach one’ visualising Black intellectual life in Handsworth beyond the epistemology of ‘white sociology’, shows how the conference statement by the UK delegation at the 6PAC meeting was critical of the inherent racism of their social condition in England’s metropolitan cities as well as of the racist ways they were being studied by white social scientists at the time. Through their own Pan-African centred and anti-colonial critique, the delegation used ‘scientific socialism’ to situate their political struggle within a global context of anti-imperialist resistance movements.

Inside this hive of Black intellectual activism emanating from Birmingham, the archival work of Vanley Burke is particularly noteworthy. Born in St Thomas, Jamaica in 1951, Burke recalls receiving a gift of a camera sent by his mother from England for his 10th Birthday. He became fascinated by the ‘magic of photography’ and was compelled by both the science and artistry of this medium (Sealy 1993). Since the early 1970s, Burke has documented the lives of Caribbean communities in Birmingham with an intimacy and sensitivity towards the people he shares the city with.

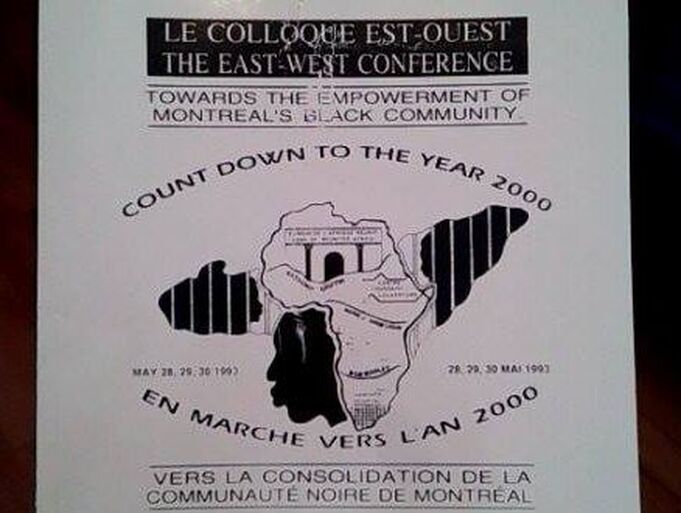

While tourists know Montreal for its cafés, festivals and old-word European 'charm'*, locals also know its boundaries that divide the city into an Anglophone West and a Francophone East. Montreal’s Black community usually occupies space according to this prevailing language divide: Black Francophones on the East side, and Black Anglophones on the West side. This pattern has had implications for relationships among Black Montreal residents, as well as for their organisation and political possibilities. Indeed, after the rise of Quebec nationalism starting in the 1960s -- which made the French language 'the distinguishing characteristic of ethnic identity' (Thomson 1995) -- it has been somewhat challenging for Black people to organise as Black people, rather than linguistically-specific 'Anglo' and 'Franco' Black communities.

Adding to the rich literature on how space and place are inherently racially produced and lived, my Identities article, 'Black in the city: on the ruse of ethnicity and language in an antiblack landscape', helps to elucidate how the politics of language and ethnicity do not occlude the ways in which race and antiblackness configure the city. |

|

Explore Identities at tandfonline.com/GIDE |

|

The views and opinions expressed on The Identities Blog are solely those of the original blog post authors, and not of the journal, Taylor & Francis Group or the University of Glasgow.