|

|

|

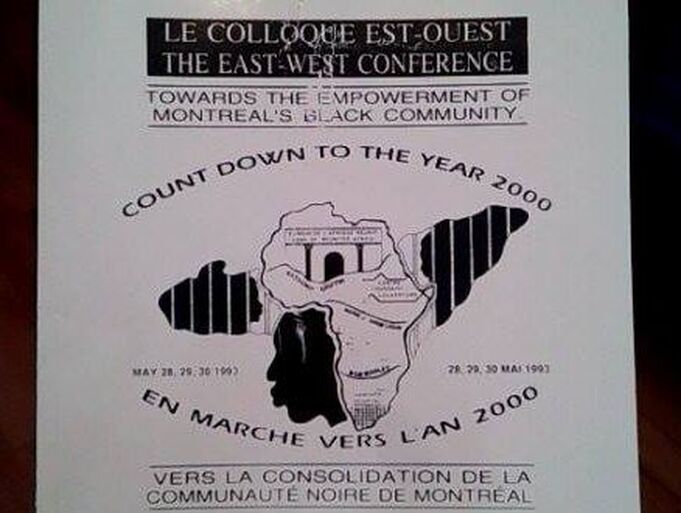

While tourists know Montreal for its cafés, festivals and old-word European 'charm'*, locals also know its boundaries that divide the city into an Anglophone West and a Francophone East. Montreal’s Black community usually occupies space according to this prevailing language divide: Black Francophones on the East side, and Black Anglophones on the West side. This pattern has had implications for relationships among Black Montreal residents, as well as for their organisation and political possibilities. Indeed, after the rise of Quebec nationalism starting in the 1960s -- which made the French language 'the distinguishing characteristic of ethnic identity' (Thomson 1995) -- it has been somewhat challenging for Black people to organise as Black people, rather than linguistically-specific 'Anglo' and 'Franco' Black communities.

Adding to the rich literature on how space and place are inherently racially produced and lived, my Identities article, 'Black in the city: on the ruse of ethnicity and language in an antiblack landscape', helps to elucidate how the politics of language and ethnicity do not occlude the ways in which race and antiblackness configure the city.

Organising across the language became crucial for Black activists in the East-end boroughs of 1990s Montreal as they fought against white racist attacks and tactics meant to push them out. Indeed, the 1990s are noted in the Montreal Black community for an increase in antiblack violence from the police and other state bodies, as well as acts of everyday terror from the white citizenry. For instance, in the autumn of 1989, a group of Black students formed the group 'Also Known as X' (AKAX). Their main goals were to organise and bring together the Anglophone and Francophone Black communities against police violence, to raise historical and political consciousness, to strengthen cultural identity and to develop economic autonomy.

Taking seriously that race always organises the geography of a place allows us to pay attention to how Black people spend much of their lives searching for ways to halt and/or undo the constraints that enclose them in states of unfreedom. In political organising, these activists articulated new Black identities and geographies. They transcended the prevailing boundaries of the nation-state, as well as the intra-city boundaries between East and West, to constitute a global Black subject position. Key to my article were the oral histories I conducted with Black activists who lived during these events and were able to comment on white narratives of them (Stoler 2002). Until this research, existing documents from interviews that had been conducted in the 1990s with Montreal Black youth offered a Quebec nationalist — even colonial — interpretation of Black identities and solidarities, a skewed understanding of Black youth’s relationship to the Quebec state and its white citizenry, and a rose-colored portrait of the future of antiblackness in the province. These documents reveal a clear desire to convince francophone Black youth to rally around Quebec white society, and steer them away from organising towards freedom dreams that stretch from Montreal to all corners of the Black Atlantic. As more incisive work continues to explore the history and the impact of Black organising and Black political thought in Canada, it will expand our scholarly understanding of Black radicalism takes form in the context of Quebec (Maynard 2017; Walcott & Abdillahi 2019). Learning about the Black history of Montreal has served as a point of departure to interrogate other Black political manifestations in the rest of the province, as well as the influence and impact Black activism in Montreal has had on other parts of the diaspora. * I use quotation marks because most people refer to Montreal’s old-world European aesthetic as 'charming.' However, that period being defined by slavery, conquest and coloniallism, 'charming' is not how how a Black radical approach would define the numerous place markers of that (continued) history in Montreal. References: Maynard, R. 2017. Policing black lives: state violence in Canada from slavery to present. Halifax: Fernwood Publishing. Stoler, A. 2002. Carnal knowledge and imperial power: race and the intimate in colonial rule. Berkeley: University of California Press. Thomson, D. 1995. Language, identity, and the nationalist impulse: Quebec. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 538: 69-82. Walcott, R. & I. Abdillahi. 2019. BlackLife: post-BLM and the struggle for freedom. Winnipeg: ARP Books.

Blog post by Délice Mugabo, CUNY Graduate Center, USA

Read the full article: Mugabo, Délice. Black in the city: on the ruse of ethnicity and language in an antiblack landscape. Identities: Global Studies in Culture and Power. DOI: 10.1080/1070289X.2018.1545816

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

|

Explore Identities at tandfonline.com/GIDE |

|

The views and opinions expressed on The Identities Blog are solely those of the original blog post authors, and not of the journal, Taylor & Francis Group or the University of Glasgow.