|

|

|

The global Indigenous Rights movement emerged late in the twentieth century, with scholars tracing its origin to postwar international conventions and human rights activism. In my Identities article, ‘World War II and the development of global indigenous identities’, and in a forthcoming book (War at the Margins, University of Hawai’i Press, 2022), I examine how the war created conditions favouring the emergence of Indigenous identity as a form of global political action.

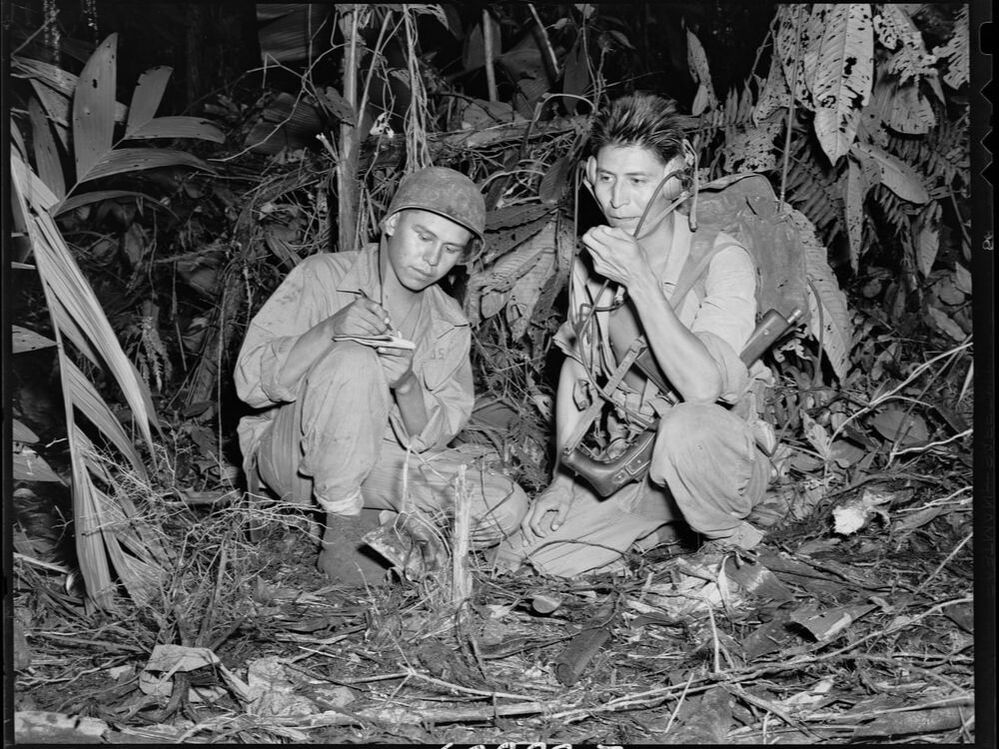

The Second World War mobilised human and natural resources on a massive scale; its aftermath dissolved empires and rearranged the international order. Indigenous men and women — those in small-scale, often tribal, societies at the fringes of national or imperial control — were drawn in as soldiers, scouts, laborers and victims. New Zealand’s Māori Battalion, Navajo codetalkers in the US Marines, Naga guides for the British Army, New Guinean carriers for Allies and Japanese — these and other Indigenous actors shaped the progress, and sometimes the outcome, of campaigns. Even where front lines did not cross Indigenous homelands, civilians suffered violence, displacement, military occupation, economic and social disruption and forced labour. War created a fluid context for change, highlighting the ambiguous legal position of Indigenous people and altering government and public views of them.

0 Comments

Our identities reflect our relationships with places and spaces. The changing contexts of these relationships also impact, shift and mould our identities. In our Identities article, ‘Hybrid identities: juxtaposing multiple identities against the ‘authentic’ Moken,’ we explore Moken[i] communities living in coastal areas of Thailand, and the Indian Ocean tsunami of 2004. We also spotlight ascriptions of Moken identities as vulnerable, overwhelmingly linked to the sea and with limited opportunities for agency over their livelihoods.

In challenging these ascriptions through our ethnographic research, we found myriad examples of agency with various beliefs, settlement patterns and usage of the sea. The communities we spoke to explained shifting identities, across and between physical spaces of settlement, but also among traditional practices and aspirations for younger generations. That our identities shift and flux is a position made overwhelmingly clear during the past year when the spread of COVID-19 has significantly changed our capacity to relate to different places and spaces. Our experiences of this past year have been contingent on national contexts and structural inequalities, as well as long-held assumptions about certain cultural identities.

The territorial realization of the Israeli state produced a new category of stateless people: Palestinian refugees. Those expelled from their homes, villages and land during the onset of the Nakba (catastrophe): a large scale ethnic cleansing process executed in 1947-48 Palestine, has resulted in the creation of one of the largest and longest standing protracted refugee communities world-wide today. The unresolved question of Palestinian displacement raises important considerations in, what scholars of redress have named, an era of settler colonial reparations. One line of inquiry that remains relevant for thinking about the future of redress to Palestinian displacement is the following: How did an Indigenous Palestinian society with historical ties to land come to be internationally governed as refugees external to the land? Further, how might we think about the history of redress and humanitarianism in the early years of Palestinian displacement as one tied to a broader genealogy of race and settler colonial formations in Palestine?

In Latin America, the indigenous question has acquired an undeniable importance in contemporary debates regarding national identity. After centuries of invisibility and denial, indigenous peoples have stood up once more against forced assimilation and segregation. The current political and social visibility of indigenous peoples and the exaltation of the values they embody are unparalleled in the modern history of the Andean countries. Although they are still victims of different forms of violence and segregation, the multicultural turn has created a structure of legal opportunities for the mobilisation of identity. It seems that Latin American subjects are no longer ashamed, nor afraid, of calling themselves indigenous.

In a historical and social context in which the term 'indigenous' still has a negative connotation that may entail discrimination and segregation, it is somewhat disconcerting that certain populations claim that they are indigenous. My Identities article, 'Legal indigeneity: knowledge, legal discourse and the construction of indigenous identity in Colombia', focuses on how legal discourse manages the challenge that indigenous revival poses to legal categories grounded on colonial definitions of national identity. In order to do so, a historical depiction of legal cases is made, showing how legal discourse absorbs postcolonial narratives on indigenous peoples, as well as more contemporary expertise knowledge accounts of cultural difference. |

|

Explore Identities at tandfonline.com/GIDE |

|

The views and opinions expressed on The Identities Blog are solely those of the original blog post authors, and not of the journal, Taylor & Francis Group or the University of Glasgow.