|

|

|

Blog post by Annavittoria Sarli, University of Birmingham, UK

Policy and media discourses in Italy refer to migration-related issues mostly in the language of emergencies, deviancy or alleged cultural threats. The everyday presence of ethnic minorities as a permanent constituent of society is rarely acknowledged. Such public discourse perpetuates a kind of socio-cultural immaturity, making it difficult for the population to accept growing diversity. ‘Italianness’, moreover, tends to be conceived as monoracial and monocultural. This idea of national identity drives an imagined net division between a monolithic national ‘us’ and ‘the others’ foreigners, who comprise both first generation migrants and their Italy-born descendants. It is an imaginary enshrined in the Italian law on citizenship, introduced in 1992 and never updated since then. Mainly based on jus sanguinis, it poses obstacles for migrant immediate decedents (MIDs) to become citizens of the country where they spent most of their lives.

0 Comments

As a team of international scholars with Czech and US origins living in Czechia and Austria, the 2015 ‘refugee crisis’ hit us in contrasting ways with regard to different regimes and their attitudes towards refugees from Syria and other Middle Eastern countries. While Czechia accepted just twelve refugees under the EU’s quota system, the Austrian public broadcasting station FM4 changed its jingle from ‘You're at home, baby’ to ‘Refugees, welcome’.

Seven years later, as we finalized work on our Identities article, ‘I always felt I have something I must do in my life’: meaning making in the political lives of refugee non-citizens’, the situation had somewhat reversed. In the spring of 2022, the streets of Prague were filled with Ukrainian flags, Czechia had accepted over 300,000 refugees in just a few months, and people became emotional regarding the war, while Austria, as a ‘neutral’ country and a non-member of NATO, was considerably more reserved.

What does a Thai person look like? How do expectations about citizenship create an ethicized cultural phenotype? In our Identities article, ‘Turbaned northern Thai-ness: selective transnationalism, situational ethnicity and local cultural intimacy among Chiang Mai Punjabis’, we explore family histories, selective transnationalism and regional Lanna identities among Thai citizens with Punjabi heritage and selective cultural identity. This article argues that Punjabi Thais maintain their networks and cultural connections with a historic ancestral homeland, but they also cultivate forms of local cultural intimacy in ways which leapfrog the linguistic and cultural hegemony of Thai national identity. In other words, despite their non-Thai appearance, these Punjabi Thais have deeply local cultural knowledge, speak Northern Thai language fluently and have Northern Thai cultural sensibilities.

Thanks to decades of critical scholarship in the social sciences, it is now common for scholars to reflect on their positionality vis-à-vis research topics and subjects and to demonstrate awareness of the power structures that shape their knowledge production. While this often amounts to deliberations about one’s individual identity in terms of race, gender, class, sexuality, ability, etc., scholars are rarely expected to question the ideological assumptions that underpin how they, both as individuals and as members of societies, make sense of the world. Taking certain ideological positions for granted as universal – liberal, secular, individualist, etc. - presents a problem in the study of political life-worlds that claim to offer alternatives, especially those with revolutionary system change on their horizon.

In my Identities article, ‘Stateless citizenship: 'radical democracy as consciousness-raising' in the Rojava revolution’, published in the special issue ‘Radical Democratic Citizenship: From Practice to Theory’, I write about ways in which protagonists of the self-determination system that has been in the making in majority Kurdish regions of Northern Syria since 2012 imagine their political struggles as a long-term effort for liberation from capitalism, patriarchy and the nation-state. I argue that this amounts to a decolonization effort that – in the words of my interlocutors – beyond the concrete work of building institutional infrastructure, aspires to transform dominant ‘mentalities in society’, including patriarchal and statist thinking which developed over thousands of years of power and domination. While sharing fragments from my fieldwork in Rojava, I decided to consciously center the ideology of the Kurdistan freedom movement, as articulated by imprisoned political leader Abdullah Öcalan, in my conceptual framework.

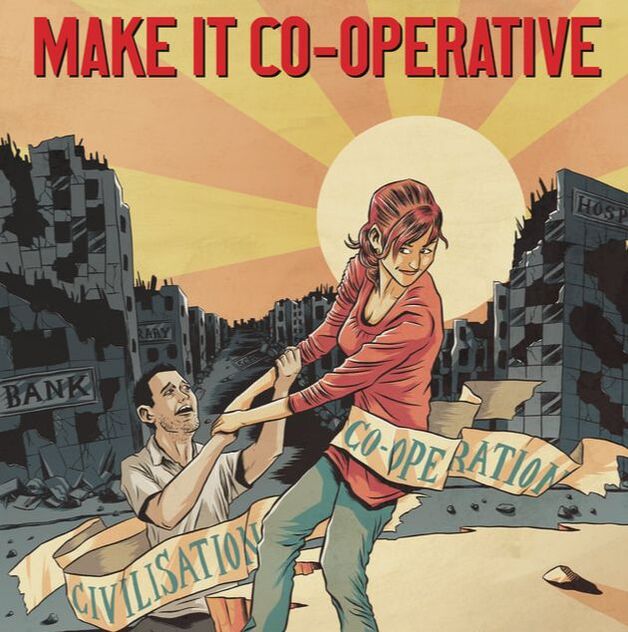

The work of workers’ co-operatives and their worker-members hold great relevance in politically and economically rather dismal times. My Identities article, ‘Radical democratic citizenship at work in an adverse economic environment: the case of workers’ co-operatives in Scotland’, explores five workers’ co-operatives in view of how they collectively and democratically make decisions as well as give space, therein, to personal matters and circumstances of the worker-members.

A few words on the dreary economic and political backdrop. In the current context, we look back at a history of decades over which the political system we know as (representative) democracy has been hollowed out and populated with corporate interests ). Oligarchs hold political offices and wield power over policy makers through powerful lobbies and politicians move between political and top-salaried corporate offices. The massive lack of declared annual revenues by directorship-holding politicans may well be seen as testimony to the deficit in holding politicians accountable. Cronyism prospers amongst the economic and political elite as public money is secretively being handed out to the hands of corporations. In an interview, Oskar Lafontaine, once member of the Schröder cabinet in Germany, dispels the myth about Germany being a democracy but in fact an oligarchy. According to Devenney and Woodford, this holds true about the UK, too. At the same time, according to the British Social Attitudes Survey, the UK demonstrates a record high of distrust in the government – down to 15% in 2019.

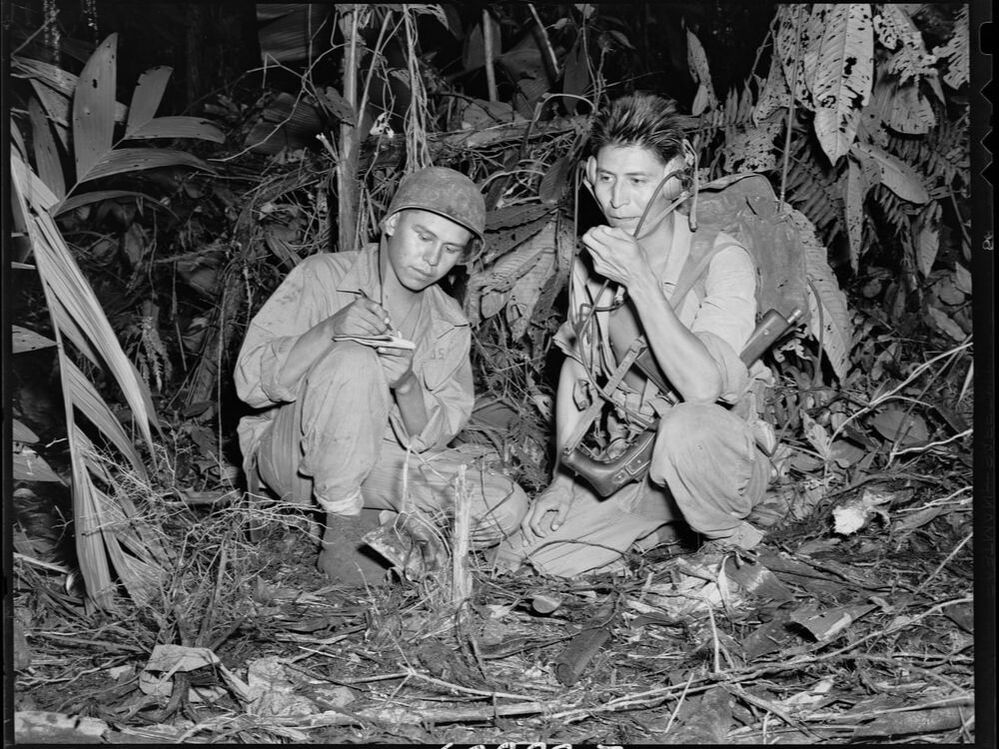

The global Indigenous Rights movement emerged late in the twentieth century, with scholars tracing its origin to postwar international conventions and human rights activism. In my Identities article, ‘World War II and the development of global indigenous identities’, and in a forthcoming book (War at the Margins, University of Hawai’i Press, 2022), I examine how the war created conditions favouring the emergence of Indigenous identity as a form of global political action.

The Second World War mobilised human and natural resources on a massive scale; its aftermath dissolved empires and rearranged the international order. Indigenous men and women — those in small-scale, often tribal, societies at the fringes of national or imperial control — were drawn in as soldiers, scouts, laborers and victims. New Zealand’s Māori Battalion, Navajo codetalkers in the US Marines, Naga guides for the British Army, New Guinean carriers for Allies and Japanese — these and other Indigenous actors shaped the progress, and sometimes the outcome, of campaigns. Even where front lines did not cross Indigenous homelands, civilians suffered violence, displacement, military occupation, economic and social disruption and forced labour. War created a fluid context for change, highlighting the ambiguous legal position of Indigenous people and altering government and public views of them.

Cities represent simultaneously one of the crucial evolving realities and at the same time blind spots in the interdependent political and economic order of the early 21st century. This order is dominated by usual suspects of states, corporations and their cross-border operations, and international organisations, as well as occasional rogues such as criminal networks, armed groups or unruly territories and polities. Yet cities are major battlefields of social and political struggles of our time as well as primary theatres of violence and war.

Exclusions, enclosures and fences, incorporating both visible and invisible walls, are the growing reality of our urban experience. This is where global flows of capital demonstrate their splendour in concrete and glass, in luxury apartments and glittering skyscrapers, even swimming pools in the sky exclusively for the rich. The wealth attracts misery to keep the whole unequal organism alive and the contemporary misérables live in ruined neighbourhoods, distant suburbs and slums.

The recent visit by Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi to Bangladesh to attend celebrations marking 50 years since the birth of the country following the Liberation War in 1971 has drawn attention to the difficult task of building a nation on the back of a brutal and bloody civil war. At least four people were killed by police in the Bangladeshi city of Chittagong during a demonstration against Modi’s visit. Protesters from Hefazat-e-Islam Bangladesh, and counter protestors aligned with Bangladesh’s governing Awami League party, represent the central divide in Bangladeshi politics, between those who tie national identity to Islam and those who tie national identity to ethnicity and the Bengali language. This is a divide sometimes understood as one between those who ‘collaborated’ with the Pakistani military and those who participated in the independence struggle. On the Golden Jubilee of Bangladesh’s birth, this divide continues to shape Bangladesh’s political landscape today.

Using the case of the ‘Urdu-speaking minority’ in Bangladesh, my Identities article, ‘Displacement, integration and identity in the postcolonial world’, considered what the experience of minorities displaced during the Liberation War tells us about the Bangladeshi national imagination today. Their own voices, and the narratives of identity and integration in which they are situated, are revealing of the nature and boundaries of the nation state fifty years on from the country’s birth. Although the country remains divided around the role or significance of religion versus culture, and between those who ‘collaborated’ with the Pakistani military and those who participated in the independence struggle, there are older divides at work here too. Some of those who ended up on the wrong side of the Liberation War are accepted into the nation today. Here colonial narratives of ‘population’ versus ‘people-nation’, ‘community’ versus ‘citizen’ structure exclusion not only through narratives of the country’s foundation myth (as commonly assumed) but also through poverty and social space.

In the 1950s, the world famous American-born entertainer Josephine Baker, who lived in France, toured the US. She was refused in 36 hotels in New York because she was black.

Back in France, Baker adopted twelve children from 10 different countries in order to prove to the world that people of all ‘races’ and religions could live together. She organised tours through the castle where she lived with her ‘rainbow tribe’ and made the children sing and dance. In the 1920s and 1930s the popular novelist Pearl S. Buck adopted seven children, four of whom were labelled ‘mixed-race’. By doing so she flaunted American restrictions on mixed-race adoptions. In the 1950s, Buck said she did so because she wanted to show that families formed by love – devoid of prejudices based on race, religion, nation, and blood – were expressions of democracy that could counteract communist charges that America’s global defence of freedom was deeply hypocritical. The adoptions by Baker and Buck were political statements that illustrate that intercountry adoptions were frequently about much more than saving a child, as many people who defended adoptions claim. My Identities article, ‘Parenting, citizenship and belonging in Dutch adoption debates 1900-1995’, explains why debates on this issue continued, without ever reaching a conclusion. Celebrities (including Madonna, Angelina Jolie and Brad Pitt) followed in the footsteps of Baker and Buck. Non-celebrities copied behaviour and arguments. Adopters tried to show that children and adults not connected by blood ties could form a family, and that single parent adoptions or adoption by same sex couples could work. Critics pointed to child kidnappings, trafficking, ‘baby farms’ and a profit-driven industry based on global inequality. Adoption was not a solution to poverty, nor in the best interest of the child, in their view.

In France and Belgium, residence permits issued to migrants from the global south married to French or Belgian citizens have consistently risen since the mid-1990s. These unions – depicted as a legal loophole that give migrants cover to secure residency, sometimes by taking advantage of unsuspecting citizens, and as fuel for ‘ethnic separatism’ when migrants marry citizens of migration background – have been targeted by law reforms in the 2000s designed to discourage them and hurdle consequent applications for temporary and permanent residence, and citizenship acquisitions.

My Identities article, ‘Family rights-claiming as act of citizenship: an intersectional perspective on the performance of intimate citizenship’, examines the enforcement of such provisions and its climate from the standpoint of French and Belgian citizens who want to marry or are already married to non-European migrants. Precisely, it draws on the experiences of national partners who, seeking legal help from non-governmental organisations (NGOs), participate in their advocacy actions. Some partners wish to overcome minute, intrusive and discretionary migration controls and administrative blockages for marrying or applying for residence, while others seek the annulment of their marriage claiming to have been cheated by their migrant partners. Although diametrically opposed, the intimate and administrative experiences of these partners erode the boundaries between their intimacy and citizenship.

Interviewer: ‘What do you think it means to be British?’

Miriam: ‘It is a passport. To be British now, I’m sorry to say this, but it is a passport. That is it. That is what being British means to me… I have lost faith in the country which I used to call home. I have lost faith, I have lost trust. Every single bit of pride that I had to be calling myself a British citizen has almost gone out of the window. They have basically sucked every single bit of love for the UK out of me.’ Miriam’s story Miriam’s husband had been in the UK from his teens but was recently forcibly removed from the country, after a traumatic period incarcerated in immigration detention. The authorities have advised Miriam that she should choose between staying in the UK alone or leave to be with him. She’s choosing the latter: ‘I just said stuff it, if England don’t want me to live here, I will live in any country in the world with him, and that is it.’

In recent years border walls have been built in different parts of the world in order to stop irregular migration. However, barriers for migrants are not only constructed physically but also discursively in political discourses. It is known that restrictive policies in Europe are accompanied by exclusionary discourses on national citizenship for immigrants, depicting them as either ‘deserving’ or ‘undeserving’.

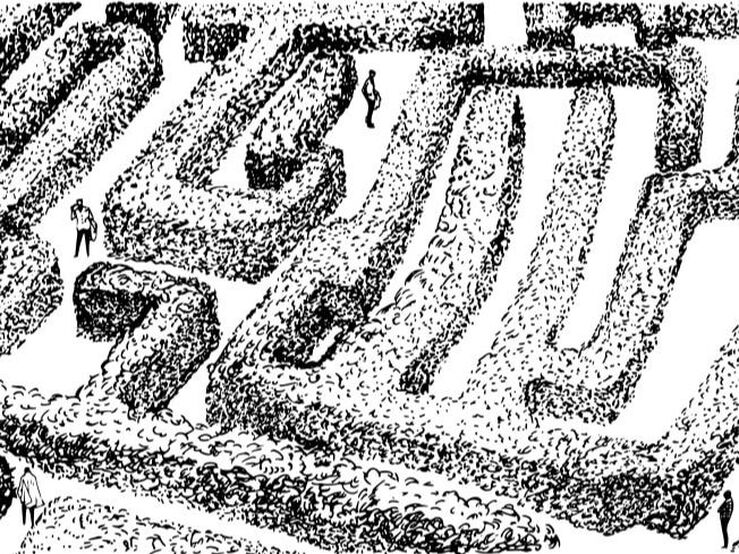

Empirical studies have demonstrated that the representation of immigrants and their citizenship in policies plays an important role in how these policies are received and acted upon, both by the host community and the immigrants themselves (da Lomba 2010; Stewart and Mulvey 2014). As such, studying political discourses might contribute to the understanding of the socioeconomic and political incorporation of immigrants into the host community. In the study presented in my Identities article, 'The labyrinth towards citizenship: contradictions in the framing and categorization of immigrants in immigration and integration policies', my co-author and I aimed to fully grasp how immigrants were framed in immigration policies in Belgium. Although previous studies have treated immigration and integration policies as distinct fields, we argue that a combined analysis of these two policy domains is needed in order to comprehend the full complexity of immigration policy. By mapping the different representations of immigrants in the wider policy field, we found that this is much more complex than the generally adopted contrast between deserving and undeserving suggest. |

|

Explore Identities at tandfonline.com/GIDE |

|

The views and opinions expressed on The Identities Blog are solely those of the original blog post authors, and not of the journal, Taylor & Francis Group or the University of Glasgow.