|

|

|

Blog post by Fraser McQueen, University of Bristol, UK

Anxieties were running high on Sunday as French voters went to the polls in the second round of this year's legislative elections. At a time of rising support for the far right across Europe – and with France's current centrist administration having already passed hard-line anti-Muslim and anti-migrant policies – most observers believed that the far-right National Rally (RN) would emerge as the nation's strongest party. An overall majority seemed unlikely, but possible. The eventual result was very different: a shock victory for the left-wing New Popular Front (NFP). The RN and its allies finished third, with the 'centrist bloc' composed of President Emmanuel Macron's party and its allies coming in second. The far right was kept out through a resuscitation of what was historically labelled a 'Republican front'. As the second round of voting approached, an unprecedentedly high number of three-way contests in various constituencies looked likely. Many (although not all) candidates from either the left or centrist blocs therefore stood down, asking their first-round supporters to support an opponent better placed to beat the RN.

0 Comments

Blog post by Bridget Anderson, University of Bristol, UK and Ioana Vrabiescu, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, Netherlands

The European Union presents itself as a global champion of human rights, yet its external borders are marked by hostility, surveillance and death. There is also an intricate network of borders within Europe that marginalizes and excludes migrants and asylum seekers. The vast majority of those excluded at the border and within Europe are people of colour. Two contemporary developments shape the context of our Identities Special Issue, Affective Control: The Emotional Life of (En)forcing Mobility Control in Europe – the global social movement for Black Lives and the COVID-19 pandemic. They have shaped conversations on structural racism and crisis-driven migration management and exposed the intersectionality of emotions and policies. For example, the invocation of national protection measures in the context of COVID-19 allowed European states to enforce border security under the guise of health protection, emphasizing the emerging pattern of governing migration through crisis management.

Blog post by George Newth, University of Bath

In late December 2023, UK prime minister Rishi Sunak gifted his Italian counterpart, Giorgia Meloni, an early Christmas present: his speech at the so-called Atreju rally organized by Meloni’s far-right Fratelli d’Italia (Brothers of Italy) party, contributed to a further legitimization and mainstreaming of far-right politics in Europe. By focusing predominantly on migration, Sunak employed a racist, xenophobic and nationalist discourse. When used by mainstream politicians, such narratives hold the power to euphemize, legitimize and normalize the politics of fear and hatred promoted by the far-right. Sunak’s appearance came barely a year after Meloni’s victory in the 2022 snap elections in Italy. The results of this poll marked a watershed moment in what has been a gradual but steady normalization, mainstreaming and rehabilitation of the far-right following the end of the Second World War. Meloni is Italy’s first far-right prime minister since 1945, and Fratelli d’Italia – the leading party in Italy’s current governing majority - has roots in Italy’s fascist past. In the weeks leading up to the 2022 elections, one of Meloni’s key discursive strategies was to depict her party as ‘centre-right’ and ‘conservative’. Since then, Meloni’s self-representation as a ‘moderate’ has been helped considerably by mainstream voices; Sunak’s speech in Rome was the latest step in this disturbing process. Where can Others turn? On (de)coloniality, messy refusals and alternatives to Eurocentric modernity19/7/2023

Blog post by Ali Kassem, National University of Singapore

Over the past years, decolonization has emerged as a key project, discourse, and buzzword across academic and public debates. Within this has been a growing recognition of the nature of Eurocentric hegemony, ongoing global connected coloniality and various pressing global crises. A growing movement to contest Eurocentric modernity and its narratives across scales: from anti-racism to ecological resistance has consequently grown and been increasingly hollowed, demonized and attacked. In researching forms of inequalities and racisms in Lebanon, focusing on the country’s Muslim communities, my research has identified a significant anti-Muslim racism pervading the lives of Lebanese Muslims. Deeply structured by and entangled with Eurocentric/modernity coloniality and articulated at the intersection of the (historical and contemporary) local and global, this anti-Muslim racism emerges as a key axis of coloniality’s assault, erasure and violence at the level of everyday lived experiences. Bringing to fore the presence and prevalence of anti-Muslim racism within the Arab-majority world, the eastern Mediterranean and Muslim communities themselves, my work has offered a series of contributions in rethinking the so-called Middle East, racism and Islamophobia studies, as well as the global workings of coloniality beyond the Atlantic.

Recent UK Home Secretaries have condemned the toppling of a slave trader statue in Bristol, dismissed footballers taking the knee as ‘gesture politics’ and called on police forces to spend less time on diversity and inclusion initiatives. Yet between 2010, when the Conservatives came into power, and 2020, the overall policy framework remained broadly favourable to multiculturalism: accommodations are still made for ethno-religious dress, the BBC has retained its mandate to reflect diversity, and funding is available for ethnic organisations.

With respect to immigration, there has been a closer connection between harsh rhetoric and restrictive measures, exemplified by the multiplication of immigration checks, the end of free movement with the EU, the housing of asylum seekers in inadequate and overcrowded military barracks and the on-going attempt to deport some to Rwanda. At the policy level, therefore, efforts to include racialized citizens seem to have become disconnected from the opening of the country to foreign nationals. Shift the focus from the Government to minority ethnic and anti-racist organisations, however, and the picture starts to look quite different. In September last year the Muslim Council of Britain echoed a report from the Institute of Race Relations denouncing how British Muslims were disproportionately affected by the citizenship deprivation powers reinforced through the Nationality & Borders Act 2022. The Runnymede Trust, a leading race equality think tank, has published a number of blog posts denouncing deportations and asylum-seekers’ woeful living conditions, partly due to the denial of their right to work and access public funds. Similar claims have been raised by Voice4Change, an advocate for the Black and minority ethnic voluntary sector.

On 7 March 2023, UK Home Secretary Suella Braverman, escalating the rhetoric on and punitive approach to migration, asylum and refugees, announced the ‘Illegal Migration Bill’ and strategy to stop migrants crossing the Channel in small boats by arresting, detaining, deporting and banning those caught. In response, former football player and BBC Match of the Day (MOTD) Presenter Gary Lineker tweeted that it is ‘an immeasurably cruel policy directed at the most vulnerable people in language that is not dissimilar to that used by Germany in the 30s’. The tweet led to a backlash in which responses ranged from the claim that he was operating beyond his remit as a sport presenter (as if they have not had to discuss racism and nationalism before), that he was in breach of the BBC’s impartiality rules, and that the comparison was unhelpful. Keir Starmer, Leader of the opposition Labour Party stated: ‘I think comparisons with Germany in the 1930s aren’t always the best way to make one’s argument’. Others took offense and expressed shock that anyone could associate Britain and the current government with the lead up and precursors to Nazism and the Holocaust. Some claimed that Lineker actually referred to these explicitly in his tweet, which he did not. Former Conservative MP for Stoke-on-Trent Jonathan Gullis claimed that Lineker was calling ‘people up here’, referring to Northern ‘Red Wall’ voters, which Starmer and Labour are also targeting with anti-immigration rhetoric, ‘racist bigots, Nazis’. According to Matthew Goodwin, Lineker’s comments are an example of how out of touch the ‘new elite are from the majority of the ‘people’ from the ‘Red Wall’ to ‘Tory Shires’, and particularly those at ‘the bottom’: ‘the white working class, straight men, non-graduates, and those who cling to more traditionalist views, such as supporting Brexit’.

Gender, as expressed on namely the bodies of Muslim women, is positioned at the centre of the radical right’s linkage between migration and religion. This link is visible in the persistent debates on the ban of Muslim body-covering, which in Austria has been promoted by the Austrian Freedom Party (FPÖ) since the turn of the century.

FPÖ’s debates on the ban of Muslim body-covering – of the headscarf in kindergartens and schools or of full body-covering in public spaces – which re-emerged since 2015, illustrate that the radical right instrumentalizes the intersection of gender, body and religion in its search for new forms of governing. As I explore in my recently published Identities article, ‘Radical right populist debates on female Muslim body-coverings in Austria. Between biopolitics and necropolitics’, the radical right’s debates over female Muslim body-covering are embedded in the neoliberal reorganisation of societies and a crisis of governability, which radical right-wing actors use to implement their own biopolitical and necropolitical projects.

In the comedy special ‘His Dark Material’, Jimmy Carr joked about the Roma Holocaust:

‘When people talk about the Holocaust, they talk about the tragedy and horror of 6 million Jewish lives being lost to the Nazi war machine. But they never mention the thousands of Gypsies that were killed by the Nazis. No one ever wants to talk about that, because no one ever wants to talk about the positives.’

Carr’s joke has sparked widespread outrage – yet some voices have defended it as ‘gallows humour’. Back in 2017, the author Alexandra Erin, in a Twitter thread on comedy, wrote ‘If the person on the gallows makes a grim joke, that’s gallows humor. If someone in the crowd makes a joke, that’s part of the execution.’ And here, Carr wasn’t speaking from the gallows; those on the gallows are in fact, one of the most oppressed and discriminated against groups to this day: the Roma, and within the scope of the joke, the European Roma and Sinti targeted in the Holocaust.

Discussions of contemporary white supremacy are seemingly everywhere: the election of Donald Trump and the January 6th insurrection, the murder of George Floyd, Brexit, the rise of the Alternative Right and white supremacist violence, and the coordinated efforts to deny racism and not educate children about the history and contemporary reality of race. These loud and important flashpoints, however, can unintentionally obscure the wider function and embodiment of white supremacy. That it is global and interconnected, is about systems and structures of power and not individuals, often hides in plain sight, and does not need ‘white’ bodies to sustain its power and replication.

For over a decade I have travelled to collect field data on race, globalization, development and labour in different Global South geographies. Through these engagements similar patterns became clear: countries in the Global South were beholden to policies dictated by the Global North. National groups racialized as white, or that exhibited a proximity to whiteness, were typically in positions of political and economic power. Those racialized as Black, or represented a distance from whiteness, had the worst material conditions. These seemingly very apparent global racial inequalities were often understood, though, as not about racism but about economic development, skills, capabilities, culture – essentially, anything but race.

While the ‘Common-Sense Group’ of MPs and Lords still retain the term, during the last few years the far-right conspiracy theory Cultural Marxism has fallen out of favour within mainstream British right-wing discourses. It has been largely superseded by the pejorative use of the term ‘woke’, which originated from the fight for racial justice in the USA. This blog post examines the transition from Cultural Marxism to woke and asks what does the derogatory use of so called ‘wokeism’ offer to its patrons that Cultural Marxism doesn’t?

Cultural Marxism is a long-standing far-right conspiracy theory. According to the American far-right, The Frankfurt School of Jewish Marxist intellectuals, who escaped Nazi Germany, initiated a plan to destabilise America from within by using their supposed control of the organs of culture, including education, the media, and churches, to attack Western civilisation and undermine pride in its past. The far-right sees the progressive civic and social movements that began in the 1960s – feminism, LGTBQ+ rights, black power, anti-colonial liberation, environmentalism, and pacifism as part of Cultural Marxism’s orchestrated effort to “destroy the American way of life as established by whites”.

Cross-posted from RACE.ED

As part of my final year at university, I completed research for my undergraduate dissertation, with a focus on the racial disparities within experience and attainment in higher education institutions. Bunce et al (2019) found that whilst 78% of white students are likely to receive a ‘good degree’ (2:1 or higher) only 66% of Asian students and 52% of Black students would reach the same classification, emphasising the hidden barriers for Black students. It was obvious that there was an invisible burden that many of the Black students I spoke to felt responsible to bear. One student described it as being the “Martin Luther King of the classroom”, the constant requirement to correct racism that goes ignored by those who are not Black. Another student further reinforced this point by describing how she felt that “…they are happy to ask the Black student what they should do but I think if it was other people’s problems, they would hire someone to find a solution…” These behaviours are not confined to the classrooms at universities but it is clear that these flippant expressions of racism are entrenched in practically every institution within the UK. For example, Parsons (2009) argues that policy is reactive rather than preventative; something has to occur before any form of retrospection is ensued by the institutions involved. The racist murder of Stephen Lawrence and the Macpherson report only confirmed the beliefs of many Black British citizens already.

Patriotism is having a moment. From French President Emmanuel Macron’s claim that patriotism is ‘the exact opposite of nationalism’ to UK Labour Party leader Keir Starmer’s call for party members to be ‘proud of being patriotic’, centrist and progressive politicians are appealing to patriotism as a bulwark against the rise of right-wing nationalism. In the US, a July 2021 YouGov poll found that sixty-nine percent of respondents believed that a person could be considered patriotic while participating in a protest for racial equality.

These examples stand in contrast to other recent appeals to patriotism: an ultranationalist French political party established in 2017 took the name ‘Les Patriotes’. The Tory government has spent £163,000 on Union flags in the past two years, and has lent its support to the ‘patriotic’ One Britain One Nation campaign. And the same July 2021 YouGov poll in the US found that sixty percent of Republicans considered themselves ‘very patriotic’ – compared to only twenty-four percent of Democrats. Why is patriotism so appealing across the political spectrum? And what does this mean for the prospects of ‘progressive’ patriotism? My Identities article, ‘‘The opposite of nationalism’?: rethinking patriotism in US political discourse’, considers the multiple and contradictory – but always exclusionary – ways that patriotism has been used by politicians across the US political spectrum. Politicians of all stripes, I find, describe themselves and their supporters as patriots. Although few define the term explicitly, all frame patriotism as an implicitly positive love for one’s country. I argue that this vagueness allows politicians to position their policy agendas, and their own character, as ‘authentically’ American. Crucially, it also permits them to position their opponents as unpatriotic and, by extension, un-American. This sharpens any attacks on a politician’s opponent; even more dangerously, it hardens the borders between those who belong to the nation and those who do not. For non-citizens, migrants and racially minoritised people, appeals to patriotism bring exclusion and violence.

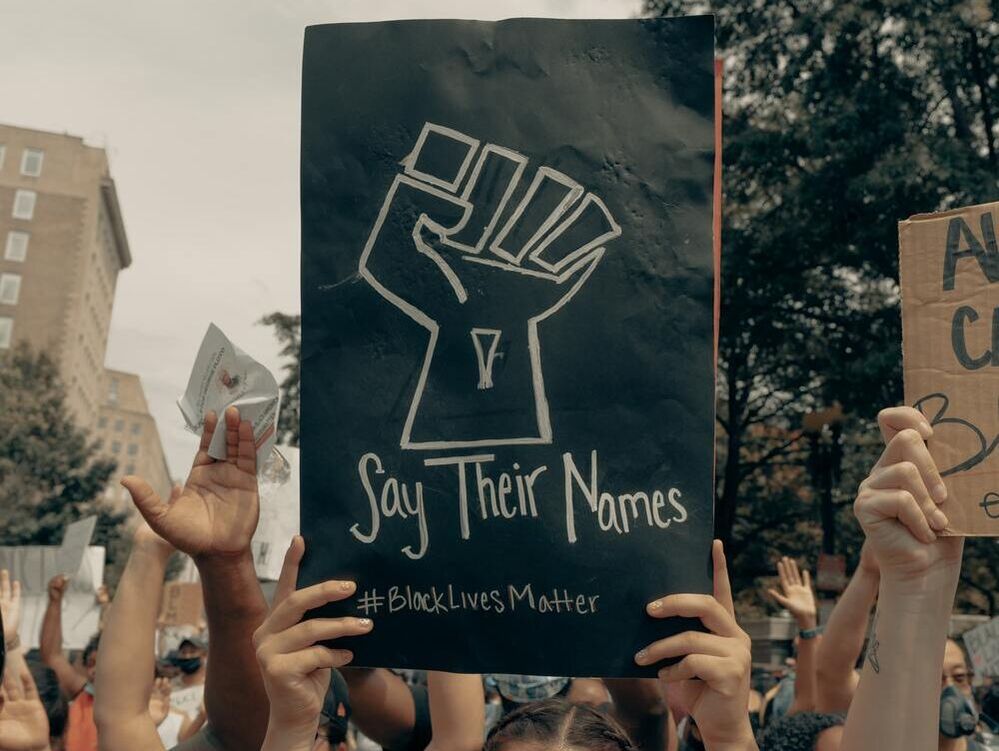

The murder of George Floyd in the spring of 2020 sparked an outcry against police brutality and racial injustice in the United States. In the wake of the killing, support for the Black Lives Matter movement rose sharply among white Americans. Shows of support ranged from the (controversial) posting of blacked-out photos on Facebook and Instagram, to patronage of black-owned businesses, to marching in BLM protests.

We are now more than a year out from George Floyd’s killing. Much of the antiracist fervour expressed by progressive white Americans in 2020 appears to have fizzled. According to a Politico/Morning Consult poll, the percentage of white Americans with positive evaluations of the Black Lives Matter movement has declined significantly since last summer. Some see this change as an indication of the superficiality of many white Americans’ involvement in antiracism. While this may be true, our Identities article, 'Racemaking in New Orleans: racial boundary construction among ideologically diverse college students', points to the important role of racial boundary construction in limiting white Americans’ involvement in antiracist efforts.

In majority white countries, the Black Lives Matter protests that unfolded after the murder of George Floyd were accompanied by the intensification of public debates on systemic racism and white allyship. Some media focused on Black-white couples, discussing the impact of these events on white partners’ understanding of anti-black racism in their Black partners’ lives. As part of the ERC-funded project ‘Regulating Mixed Intimacies in Europe (EUROMIX), over the past four years I have explored Black-white couples’ experiences of racism and discrimination in their everyday lives.

Drawing from ethnographic fieldwork I conducted in 2018-2019, my Identities article, ‘Interracial couples and the phenomenology of race, place and space in contemporary England’, looks at partners’ perceptions of dis/comfort and un/safety across different contexts: when they jointly move in public spaces, choose where to make home, and travel for leisure. By juxtaposing these scenes, the article foregrounds a multi-layered economy of constraint and choice underpinning the lives of the opposite and same-sex couples that I have met and/or interviewed.

In the wake of Colombia’s national branding as a pluri-ethnic nation, on the one hand, and of Black and Indigenous social movements denouncing racism, ethno-racial inequality, systemic necropolitics (Mbembe, 2003; Alves, 2014) and social injustice, on the other hand, Bogotá’s municipal ‘multicultural turn’ in the 2010s seemed a precious opportunity to partly reconcile the ambivalent reality of Colombia’s multiculturalism, torn as it is between the pluri-ethnic reality of its social constituencies and the simultaneous inclusion (often as commodification) and exclusion (racialisation) of its ethnic minorities.

In particular, the latest POT (Plan de Ordenamiento Territorial, or Land Use Planning) — that determines urban growth in Bogotá for a span of at least 15 years — and its first Ethnic Focus (or Ethnic Approach; Enfoque Étnico Diferencial, in Spanish) in the late 2010s, could have been an opportunity to develop an understanding of urban dynamics informed by ‘race’ and racism, whereby patterns of racialisation and antiblackness in the space of the city could be finally and formally acknowledged by the public administration and Colombian urban professionals (planners, architects, land economists, geographers, urban sociologists, etc.) — for the majority of whom urban inequality has long been conceived as a socioeconomic matter devoid of any racial inflection. However, as elsewhere in Latin America, the municipal ‘multicultural turn’ in Bogotá largely missed that opportunity. In my Identities article, ‘The governmentality of multiculturalism: from national pluri-ethnicity to urban cosmopolitanism in Bogotá’, I detail the ambiguities inherent to Colombia’s pluri-ethnic turn at the urban scale, from a situated perspective on its capital city, Bogotá: inclusive and plural in its narrative and for which concerns the extraction of value from ‘ethnic presence’ in the city, but exclusive and tailored at regulating (constraining) ‘diversity’ through its policies and planning practices.

While never entirely going away, the relationship between football fandom and racism has over the past few months come into renewed focus. In a UK context, this concerns the continued controversy over players choosing to ‘take the knee’ before professional matches in protest of racial injustice, as well as online abuse targeting the three black players who missed penalties in this summer’s final of the Euro 2020 tournament. Against a back story of overt racism in English stadia throughout the 1970s and 1980s, these episodes remind us of the need to keep interrogating the use of racist language across English football.

In this context Millwall FC holds a somewhat unique, although unwanted, position. It is a club that is widely recognised – for its association with racist hooliganism – even among those who know little about football. This reputation dates back to the 1970s. Therefore, the idea of the black Millwall fan – as a category and an identity – causes raised eyebrows, as it appears an oxymoron that goes against existing perceptions of what constitutes a Millwall fan. It is the oral histories of black Millwall fans and players that are at the core of the Millwall's Changing Communities Research Project, funded by the Lottery and led by the South London-based charity Bede House.

Cross-posted from British Sociological Association

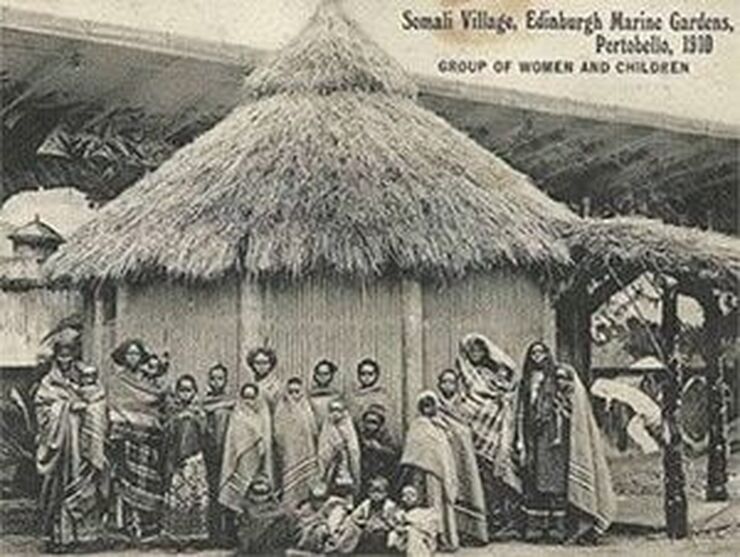

How is history written and by whom? These are questions that have been raised with frequency across the decolonising movement and in particular, by the Cadaan Studies movement, which has focused on knowledge production relating to Somali people. Started in 2015 by Harvard doctoral candidate, Safia Aidid, the movement provides a framework through which to critique the role of whiteness and white privilege in shaping narratives about Somali people. The canonical work of Glaswegian-born I.M. Lewis has come under particular scrutiny not in the least due to his twin roles as anthropologist and administrator for the British colonialists in (then) British Somaliland in the 1950s. Yet whilst the colonialist activities of a Scotsman in Somalia shaped global discourses about Somali people, the narratives of Somali people in contemporary Scotland, many of whom now live in the same area of Glasgow in which Lewis was born, remain absent from local and transnational histories. We unravel and critique this absence. Today in Scotland, there is a Somali population of up to 4000 people. The population has grown in the main since 1999, following the state-enforced dispersal of asylum seekers to sites around the UK. Despite residing in Scotland for nearly two decades, the Somali population continues to be framed in these terms, considered ‘new’, as ‘migrant’; as without history prior to arrival in Scotland and without historical links to Scotland. These narratives obscure a much longer history of Somali people living in Scotland, and of Scotland’s relationship with Somalia.

'Refugees must be taught how to best fit in': so reads the title of Times columnist Clare Foges following the fall of Afghanistan in August 2021 to the Taliban and the subsequent mass exodus of Afghan men, women and children towards Britain. This wilfully juxtaposes a ‘non-native’ other with the presumed ‘natives’ of the UK and places expectations on the new arrivals to adapt to ‘our way of life’. This emphasis on assimilation and the eradication of difference and is one of the core demands often placed on the racialised ‘non-native’, ‘foreigner’ or ‘non-integrated’ co-citizen on their arrival to the West. It is but one of many recent examples of a far right discourse of ‘nativism’ being published in a mainstream broadsheet, and passed off as ‘sensible politics’.

Much of the scholarship on the far right has taken an ‘ideational approach’ to nativism which entails the following three assumptions:

Cross-posted from Georgetown Journal of International Affairs.

Recent events in France have revealed how race remains such a loaded concept in French society. But policymakers must emphasize that this is nothing new, and that public policies need to address historical and present racism in France in order to move forward. Events in recent months have once again made race and racism part of public debate in France. There was the beheading of school teacher Samuel Paty in a banlieue, or suburban outskirt, north of Paris in October 2020. Then the beating, captured on video, of Michel Zecler, a forty-one-year-old Black music producer, by four police officers last November in Paris. These debates have even included accusations of importing Anglo-American or US conceptions of race and racism to the French context, as evident in a recent interview with President Emmanuel Macron in the New York Times and movement by his administration to investigate French universities for importing American theories. This is in addition to a proposed bill making it a criminal offense to share images of police officers on social media platforms, amid a growing mobilization against police violence targeting Black and Maghrébin-origin individuals.

Following George Floyd's horrific death and the scenes of his sensational courtroom trial which played out to public scrutiny across the world, my recently published Identities article, 'The dying Black body in repeat mode: the Black 'horrific' on a loop', addresses the notion of the recurrence of 'Black death' in repeat mode offline and its viral circulation online in the digital economy.

Digital platforms abstract dead bodies as floating matter to be consumed without context. In tandem, this 'repeat mode' produces a visuality or a 'shadow archive' to showcase Black bodies as perpetually given over to brutality, violence and foreshadowed by the possibility and actuality of constant death. The horrific killings of Blacks is sustained through police brutality against the historic context of slavery, White oppression, segregation, Black civil rights movements and an American dream forged through Black death as part of a visual regime. My article opens up with the question from a Black student posted on a research mailing list online, on the troubling phenomenon of consuming Black bodies in demise in repeat mode on the internet. The student's query bridges a number of issues including the role of the digital sphere as a virtual graveyard in shaping Black consciousness and communion, given the internet's 'body snatching' tendencies in which violence, death and bodies struggling to 'breathe' float infinitum.

Cross-posted from The Conversation.

On BBC Sport, Match of the Day pundits Ian Wright and Alan Shearer recently had a conversation about racism in football. Shearer, the white ex-England international striker asked his black ex-teammate Wright: “Do you believe a black guy gets treated differently to a white guy?” Wright’s response was unequivocal: “Without a doubt, Al!” Black players face discrimination on every level: public (anti-black racism from fans in stadiums), private (abusive DMs on social media) and institutional (lack of management and coaching opportunities). Wright, however, also pointed to the disparate treatment players receive in the press, referencing recent reports on similar property investments by strikers Marcus Rashford and Phil Foden. Rashford, who plays for Manchester United and is black, was framed an extravagant, cash-rich, cash-loose footballer. Foden, meanwhile, who plays for City and is white, was described as the local Stockport boy looking after his family. Why do we need the 'racialized' in 'racialized capitalism'?[1] In his recent article for Field Notes,[2] Charlie Post insists on the need to think racism and capitalism together but is keen to move the discussion 'beyond racial capitalism' perspectives[3] because of disagreements about the spatial and temporal origins of racism, and about the explanation those perspectives offer for the reproduction of racism in capitalist societies. While there is much to welcome in Post's carefully-crafted account, there are four areas of disagreement to which I want to draw attention. First, whatever substantive critiques one might wish to level at racialized capitalism perspectives, it is premature to speak of going 'beyond racial capitalism' or to claim that 'the notion of 'racial capitalism' is redundant [because] there is no 'non-racial' 'capitalism,' without a more thorough consideration of the political and theoretical work these perspectives perform in the present moment. Post certainly acknowledges that they emerged out of the reverberations of collective action against state racism, particularly the desire of a new generation of activists to make sense of racism's continuing power to inflict damage and death. However, there is much more that needs to be said on the matter. In particular, racialized capitalism perspectives help make transparent the constitutive role racism played in the formation and reproduction of capitalist modernity. This is no mean achievement, given that much of public discourse, along with liberal and critical thought, continues to minimize and underestimate its structuring power and significance.

Cross-posted from Spectre.

'For us who are determined to break the back of colonialism, our historic mission is to authorize every revolt, every desperate act, and every attack aborted or drowned in blood.' – Frantz Fanon, The Wretched of the Earth [1] On July 19, 2016, Adama Traore, a 24-year-old Black construction worker, was killed after an arrest by three police officers in Beaumont-sur-Oise, a northern banlieue, or suburban outskirt, of Paris. Adama was stopped for an identity check — a not uncommon measure by which police officers stop individuals and ask for their identification (often disproportionately targeting Black and Arab individuals). In this case, Adama was taken to a nearby police station and by the time he arrived, he was dead. The police originally stated that he had died of a heart attack, and then said he had prior health conditions which caused his death. In late May, the three police officers were cleared in their involvement for Adama’s death.

In an age defined by hyper-visibility made possible by always-on digital media, brought to our fingertips by the smartphone, we are regularly fed images of (often extreme) racial violence. The circulation of the long eight minutes and forty-six seconds of George Floyd’s murder by Minneapolis police officer, Derek Chauvin, in May last year reinvigorated a movement across the Global North, against the disposability of Black lives. However, there is no simple way to untangle the dilemma that there is a seeming need to witness the death of a Black person to trigger a response. As LeRon Barton wrote, ‘watching Black men being beaten on video is the new lynching postcard.’

Despite the energy unleashed by the Black Lives Matter protests of 2020, it is not surprising that many antiracists remain sceptical about the lasting commitment of those momentarily inspired by the uprising. Will 2020’s #BLM moment be superseded by a return to scrolling through images of racial violence to which we seem increasingly immune? These questions animate my Identities article, ‘Looking as white: anti-racism apps, appearance and racialized embodiment’, which looks at mobile apps for reporting on and educating about racism. As mobile technology is such a part of our everyday experience, it can clearly be a powerful tool for pedagogy. This is the aim of one of these apps, the Australian-based Everyday Racism app. The app encourages ‘bystanders’ to learn about the experiences of people of colour and Aboriginal people who face racism in their daily lives. It uses gamification to deliver text and video messages to app users about these experiences in the aim of building empathy and encouraging what Australian racism researchers call ‘bystander antiracism’ (a strange appropriation of a concept used to describe those who stood by and did nothing during the Nazi deportation of the Jews).

Media coverage of recent police killings of Black citizens, including George Floyd and Breonna Taylor, and the related Black Lives Matter protests, have reignited a long-smouldering national conversation about race in America. These acts of police violence are part of a centuries-long pattern of institutional and systemic state violence against brown, Black and Indigenous people in America.

The killings and protests have prompted responses at both organisational and individual levels. Indeed, national organisations that contribute to the (re)production of bucolic white racial identities are facing a reckoning because of a growing awareness of the ways they contribute to making this violence possible and invisible to many white Americans. For example, this year the Boy Scouts of America formally supported Black Lives Matter, instituted a new diversity and inclusion merit badge, and acknowledged, ‘We have not been as brave as we should have been because, as Scouts, we must always stand for what is right and take action...’[1] Individually, many white Americans, who may have never thought critically about their racialised identity or privilege, are working to better understand their own identities and the institutions that make up their social landscapes. Yet even as racist state violence and resistance to it are made visually manifest in the media, many white Americans are still responding with surprise, shock and outrage because they live racially privileged lives free from such state terrorism, and are able to ignore the many manifestations of ongoing systemic racism. |

|

Explore Identities at tandfonline.com/GIDE |

|

The views and opinions expressed on The Identities Blog are solely those of the original blog post authors, and not of the journal, Taylor & Francis Group or the University of Glasgow.