|

|

|

As socially committed and Spain-based researchers, we have long been amazed by the rhetorical power of the integration discourse (in this case, immigrant integration). This discourse has charmed and brought together people with different political orientations, even seducing numerous activists who usually adopt radically critical stances towards existing social oppressions (for example, capitalism).

However, such criticism does not frequently focus on integration. On the contrary, integration measures are often thought of as useful 'recipes' against racism, or even as its opposite. Hence, the 'benign' concepts associated to integration such as 'diversity', 'participation', 'active citizenship', 'interculturality', etc. have been often uncritically appropriated by non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and leftist movements, with allegedly inclusive or even anti-racist aims. The aim of our Identities article, ‘Elective affinities between racism and immigrant integration policies: a dialogue between two studies carried out across the European Union and Spain’, is to deconstruct such optimistic rhetoric, showing that racism and integration are closely embedded, and thus questioning the transformative potential of integration policies. With this aim, we have put into dialogue our PhD research pieces (one is complete, the other is being finalised), which respectively focus on the 'soft law' European Union framework for the integration of third-country nationals and Spanish/Andalusian immigrant integration policies.

0 Comments

The illusion of Britain as a post-racial society, or at least a multi-cultural society at ease with racial mixing and mixedness that the royal wedding of Prince Harry and Meghan Markle conjured up, has been wiped aside by the couple’s revelation of the racism they had faced within the royal family, including questioning about the potential skin colour of their first born. Britain may have around one in ten of couples in a mixed relationship, but clearly this does not signal antiracist progress. Meghan will have dealt with overt and covert racism all her life, but it must have been a steep learning curve for Harry. What will this mean for how he seeks to bring up his son and soon-to-be born daughter?

In my Identities article, ‘Partnered fathers bringing up their mixed-/multi-race children: an exploratory comparison of racial projects in Britain and New Zealand’, I took an in-depth look at how fathers of mixed-race children sought to equip them to deal with racism, and give their children a sense of identity and belonging. Drawing on racial formation theory, I explored the individual racial projects that they pursued for their children, interacting with historical, social and political nation state racial projects.

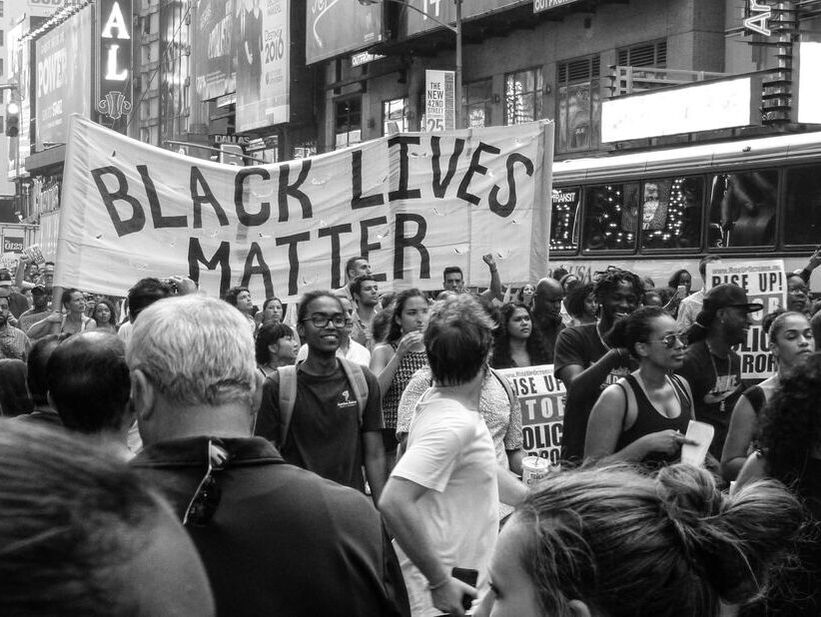

The recent Black Lives Matters (BLM) protests offer a juncture for Britain to have a broad and sensible conversation on race and racism, similar to that headed by the Clinton administration in America 20 years ago. The recent re-appearance of the debate on terminology – the question of how to refer to racialised groups in Britain – may be the beginning of this. It is not a new question but is being posed by a new generation of Black Britons, who having been born in the UK should be unfamiliar with Hall’s sense of living ‘on the hinge between the colonial and post-colonial worlds’ (Hall & Schwarz 2017, 11).

In my Identities article, ‘The stigma of being Black in Britain’, I argued that despite more than 50 years since Britain adopted its first Race Relations Act (1965), colour remains a ‘visible feature of the urban landscape’ (Hall & Schwarz 2017, 184) in the UK. I described Brexit as an indication that, as Stuart Hall wrote many years ago, many of the ‘white underprivileged…believe that what they experienced was not because they were poor and exploited but ‘because the blacks are here' (Hall & Schwarz 2017, 185).

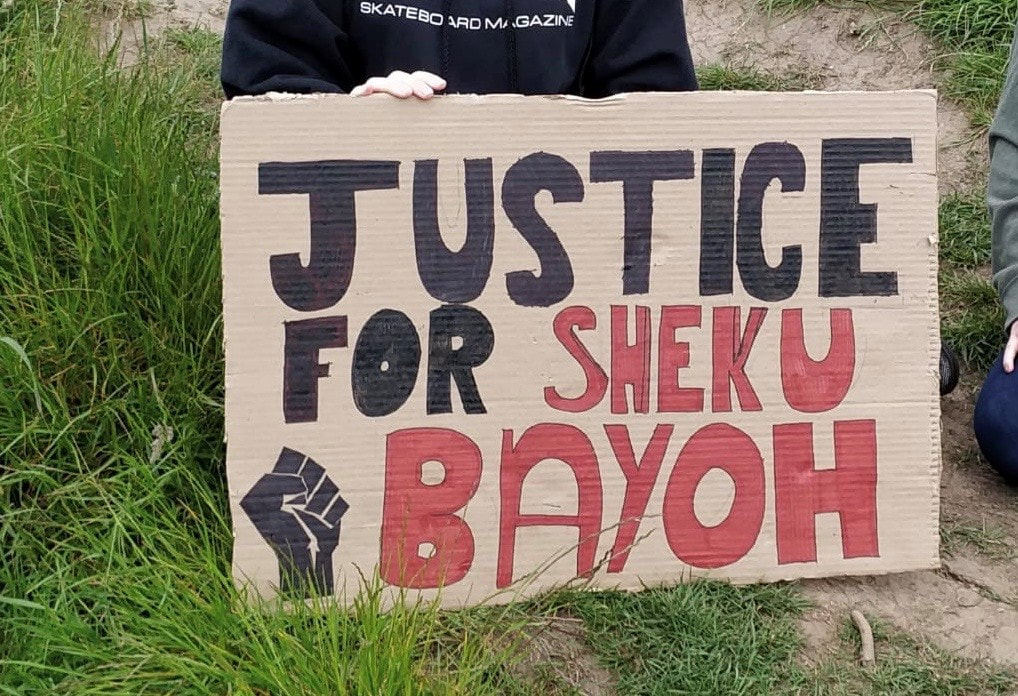

Sheku Bayoh died shortly after he was arrested by up to nine police officers in the early hours of 3 May 2015 on a quiet street in Kirkcaldy, a small town on the east coast of Scotland. Sheku’s mother had encouraged him to move to Scotland to be near his sister because she thought a young black man would be safer in Scotland than in London. CCTV footage has shown that Sheku was on the ground and restrained within less than a minute of police officers arriving, yet the postmortem revealed he had 32 injuries to his body. The Lord Advocate of Scotland announced in November 2019 that no police officer would be charged for Sheku’s death, four and a half years after Sheku died.

I wrote my Identities article, 'Containment, state racism and activism: the Sheku Bayoh justice campaign', not only to shed light on the circumstances of how Sheku died after he was arrested but to attempt to explain why deaths in police custody happen, why they are disproportionately of black people, and to develop an understanding of why the families who have lost loved ones find it so hard to get justice or even an adequate explanation from the police of why. I argue that the state has an interest in containing working class struggles and that state racism is used as part of the containment strategy that explains black deaths in police custody. I use a historical and theoretical analysis of how racism has been deployed by the state in immigration legislation where the black presence was problematised. The problematic black presence discourse has historically been a key feature of the policing of black communities – although this has evolved in several ways it nevertheless continues to produce a racial criminalisation of black people.

When writing public-facing policy-related reports, it is pro forma that the author(s) put forward a series of recommendations. Most of the time, writing recommendations is a data-/evidence-led process. What is more, some of the standard academic advice on writing recommendations includes things like ensuring that the recommendations speak directly to the aims and objectives of the project, acknowledging any limitations of the research and, where relevant, proposing further research. It also strikes me that writing recommendations can be an afterthought – a task left until the final full stop has been put on the conclusions.

Over the past seven years I have been involved in co-authoring reports on subjects ranging from the public impact of Irish Republican and Loyalist processions in Scotland, workplace racism, and more recently racism, institutional whiteness and racial inequality in higher education. Towards the end of this summer, I carried out a thematic analysis of the recommendations put forward in key government and non-governmental reports relating to racism and racial inequality in Britain on behalf of the Stuart Hall Foundation. Eight recurring themes emerged from the analysis of the 589 recommendations advanced in thirteen reports, ranging from the 1981 Scarman Report into the causes of the Brixton riots, through to David Lammy MP’s 2017 report ‘into the treatment of, and outcomes for Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic individuals in the criminal justice system’. Truth be told, this research was a depressing and blunt reminder that the recommendations put forward in reports are rarely ever acted upon, even though the report findings are typically greeted with performative enactments of shock, shame and concern. Indeed, the failure to act evidences a longstanding lack of political commitment to unsettling the coordinates of racial hegemony and disturbing orthodox ways of doing things. So much so, I am reminded of the words of the late Black novelist, playwright, essayist, poet and activist, James Baldwin, who once asked, ‘How much time do you want for your "progress?"’.

Henri Lefebvre and C.L.R. James were quintessential twentieth-century intellectuals. They were born within six months of each other in 1901. Both lived to within sight of the century’s end: James died in 1989 and Lefebvre in 1991. And, as I argue in my Identities article, 'Passing through difference: C.L.R. James and Henry Lefebvre', their grappling with the times in which they lived led them to articulate a comparable politics.

What kind of politics? One which valued human flourishing more than formal equality. One which considered creative freedom more significant than technological progress. And one which found hope in the way in which ordinary people fought against constraint in their day-to-day lives. Handsworth and the production of knowledge: Blackness, racism and anti-imperialism in 1970s Britain27/11/2019

The African Caribbean Self-Help Organisation (ACSHO), based at Heathfield Road in Handsworth, Birmingham, established itself as a central hub for Pan-African centred learning and intellectual debate in the early 1970s. ACSHO members were part of a UK-wide co-ordinating committee that sent a delegation of activists to the 6th Pan African Congress (6PAC) in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania in 1974. My Identities article, ‘Each one teach one’ visualising Black intellectual life in Handsworth beyond the epistemology of ‘white sociology’, shows how the conference statement by the UK delegation at the 6PAC meeting was critical of the inherent racism of their social condition in England’s metropolitan cities as well as of the racist ways they were being studied by white social scientists at the time. Through their own Pan-African centred and anti-colonial critique, the delegation used ‘scientific socialism’ to situate their political struggle within a global context of anti-imperialist resistance movements.

Inside this hive of Black intellectual activism emanating from Birmingham, the archival work of Vanley Burke is particularly noteworthy. Born in St Thomas, Jamaica in 1951, Burke recalls receiving a gift of a camera sent by his mother from England for his 10th Birthday. He became fascinated by the ‘magic of photography’ and was compelled by both the science and artistry of this medium (Sealy 1993). Since the early 1970s, Burke has documented the lives of Caribbean communities in Birmingham with an intimacy and sensitivity towards the people he shares the city with.

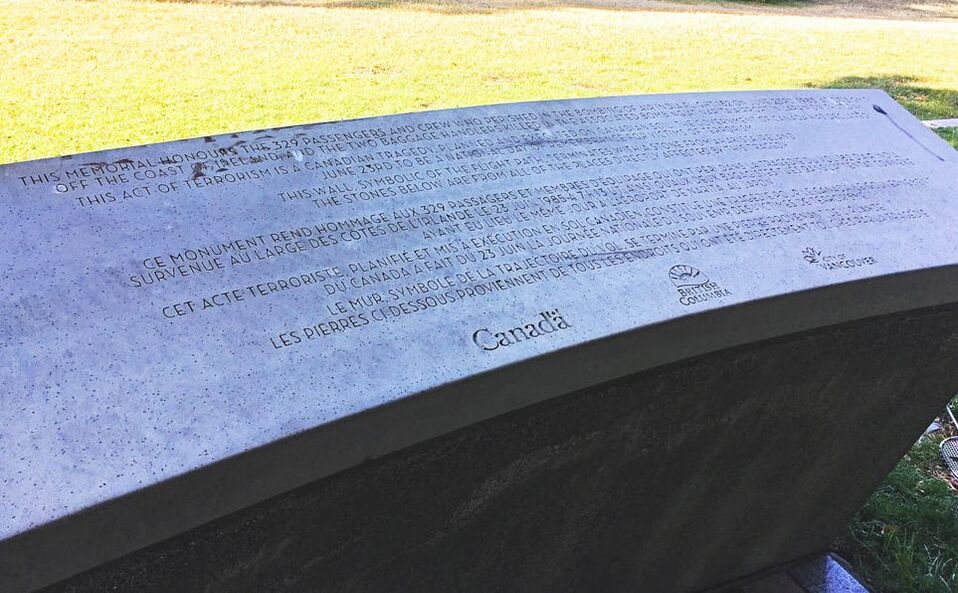

In June 1985, 331 people were killed in the bombings of two Air India flights, which investigators attributed to militant Sikh nationalist groups operating in Canada. Although the bombings are now regarded as the deadliest incident of terrorism in Canadian history, they continue to hold a complex, often contradictory place in Canada’s imaginary.

Much of the existing scholarship has attributed this complexity to systemic racism that limits how the bombings have been regarded and remembered as a ‘Canadian tragedy’ (Dean 2012, Failler 2009, Seshia 2012), even as the Canadian government devoted considerable resources to investigating and prosecuting the attacks. In 2006, the Government of Canada even commissioned a public inquiry to determine how state institutions failed to prevent and effectively prosecute the bombings. Given that the inquiry received evidence that systemic racism shaped state responses to the bomb plot, it offers a unique vantage point to examine how state institutions reckon with their implication in racial violence. 25 years after apartheid: are British-born South Africans signing up to the ‘rainbow nation’?2/10/2019

2019 marks 25 years since Nelson Mandela was elected as the first black president of South Africa. Finally, apartheid, the system of racial segregation institutionalised by the Afrikaans-led Nationalist Party in 1948, was a chapter closed. Since that time, South Africans of all backgrounds have been debating the extent to which the post-apartheid vision of ‘a rainbow nation’ -- a multicultural unity of people of many different nations -- is being realised.

This question is not only of interest and importance within South Africa. Against a context of rising populism and white nationalism across the Global North, are white people in South Africa really rejecting the privileges of white supremacism which they have enjoyed for so long? My Identities article, 'Reimagining racism: understanding the whiteness and nationhood strategies of British-born South Africans', examines this question by looking at one group of South African Whites: those who were born in Britain and migrated to South Africa. Many did so in the 1960s, 70s and 80s, through a ‘Ten Pound Pom’ scheme which offered them cheap passage, good jobs and comfortable accommodation on arrival. Whereas, at home in Britain, there was rising rejection of the apartheid system in South Africa, this group chose to up sticks and move to a deeply segregated society. How do they explain this, to others and themselves? And how do they now talk about the situation in South Africa today?

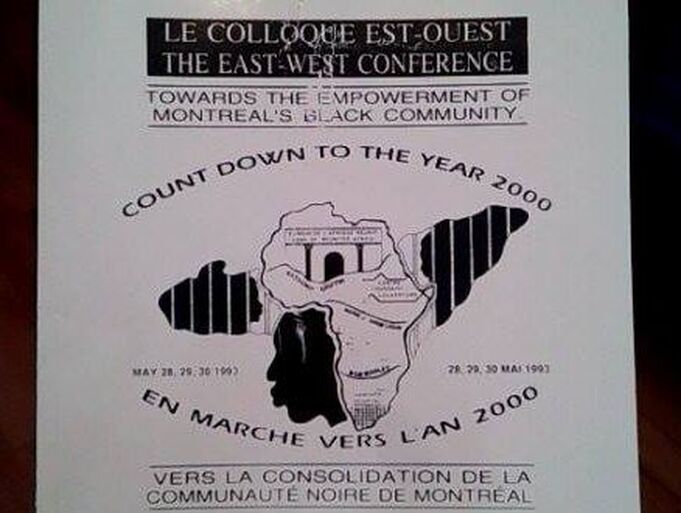

While tourists know Montreal for its cafés, festivals and old-word European 'charm'*, locals also know its boundaries that divide the city into an Anglophone West and a Francophone East. Montreal’s Black community usually occupies space according to this prevailing language divide: Black Francophones on the East side, and Black Anglophones on the West side. This pattern has had implications for relationships among Black Montreal residents, as well as for their organisation and political possibilities. Indeed, after the rise of Quebec nationalism starting in the 1960s -- which made the French language 'the distinguishing characteristic of ethnic identity' (Thomson 1995) -- it has been somewhat challenging for Black people to organise as Black people, rather than linguistically-specific 'Anglo' and 'Franco' Black communities.

Adding to the rich literature on how space and place are inherently racially produced and lived, my Identities article, 'Black in the city: on the ruse of ethnicity and language in an antiblack landscape', helps to elucidate how the politics of language and ethnicity do not occlude the ways in which race and antiblackness configure the city.

In October 2016, as the US election loomed, Farage (2016) wrote in an opinion piece in The Telegraph, a symbol of his media prominence:

The similarities between the different sides in this election are very like our own recent battle. As the rich get richer and big companies dominate the global economy, voters all across the West are being left behind. The blue-collar workers in the valleys of South Wales angry with Chinese steel dumping voted Brexit in their droves. In the American rust belt, traditional manufacturing industries have declined, and it is to these people that Trump speaks very effectively…. This kind of statement was not limited to far-right politicians claiming political support from the working class, but has become common in much of the political commentary since. To make sense of these developments, our Identities article, 'Whiteness, populism and the racialisation of the working class in the United Kingdom and the United States', examines the populist racialisation of the working class as white and ‘left behind’, and representative of the ‘people’ or ‘demos’, in the campaigns and commentaries. |

|

Explore Identities at tandfonline.com/GIDE |

|

The views and opinions expressed on The Identities Blog are solely those of the original blog post authors, and not of the journal, Taylor & Francis Group or the University of Glasgow.