|

|

|

In October 2016, as the US election loomed, Farage (2016) wrote in an opinion piece in The Telegraph, a symbol of his media prominence:

The similarities between the different sides in this election are very like our own recent battle. As the rich get richer and big companies dominate the global economy, voters all across the West are being left behind. The blue-collar workers in the valleys of South Wales angry with Chinese steel dumping voted Brexit in their droves. In the American rust belt, traditional manufacturing industries have declined, and it is to these people that Trump speaks very effectively…. This kind of statement was not limited to far-right politicians claiming political support from the working class, but has become common in much of the political commentary since. To make sense of these developments, our Identities article, 'Whiteness, populism and the racialisation of the working class in the United Kingdom and the United States', examines the populist racialisation of the working class as white and ‘left behind’, and representative of the ‘people’ or ‘demos’, in the campaigns and commentaries.

We argue that such constructions made race central, obscured the class make-up, allowed for the re-assertion of white identity as a legitimate political category and legitimised, mainstreamed and normalised racism and the far right. Moreover, it delegitimised black, minority ethnic and immigrant experiences and interests, including working class ones.

We show that the construction of the votes as (white) working class revolts, and representing the 'people' and/or 'demos', is based on a partial reading of electoral data, misrepresents the votes, stigmatises the working class, and supports an ideological purpose which maintains the racial, political and economic status quo. While much of the west has witnessed a resurgence of the far right since the end of the 2000s, 2016 marked a new step in the mainstreaming of reactionary and particularly racist, Islamophobic and xenophobic political movements, agendas and discourses (Mondon & Winter 2017). Amongst others, the Brexit victory in the United Kingdom and Donald Trump’s election to the Presidency in the United States have demonstrated that these movements, agendas and discourses can now win key electoral battles. While much has already been written on these two cases and events, the aim of our article is to focus the discussion on the construction of the white working class to promote racist agendas, adding to a limited, but growing analysis (Bhambra 2017, Emejulu 2016, Lentin 2017, Mondon 2017, Nadeem et al. 2017, Saini 2017, Virdee & McGeever 2017, Winter 2017). Our contribution is three-fold: first, to interrogate the construction of these votes, specifically as white working class revolts; second, demonstrate that the prevalent mainstream explanations about the rise of a (white) working class reaction is based on an ideological racialised construction of the working class and skewed reading of data in both cases that do not sustain even basic scrutiny; third, that such explanations and skewered data reproduce and even support a particular discourse and political agenda, legitimising Trump and Brexit, as well as racism and xenophobia, and delegitimising the working class, whether consciously or not. To achieve so, our article examines this mainstreaming of racism, focusing on the transformation of the discourses and rhetoric about race and class. Particular attention is paid to the populist racialisation of the working class as white and indigenous in the Brexit and Trump campaigns. In doing so, our aim is not to explain the reasons behind the vote for Trump or Brexit, but rather to examine such explanations and how these reproduce or even support a particular discourse and political agenda. To challenge the narrative constructing Brexit and Trump as working-class revolts, we use a two-pronged approach: first, we demonstrate that there is a long history of whitening the working class and ignoring its diversity, thus promoting an essentialist narrative based on white (male) experience. This leads us to conclude that, while racism is indeed present in the working class, its diverse nature should not be ignored and the racism present in upper classes should not be downplayed, particularly when the so-called revolt is led by the privileged (both in terms of race and wealth). We then take a more electoral approach and demonstrate that the working-class revolts for both Trump and Brexit are in fact far less obvious than the coverage of both electoral contests would suggest. In fact, the working-class nature of these two votes is marginal and can be challenged, but is mostly ignored in elite discourse. We argue that the white working class narrative as problematic in four ways. The first is that it racialises the working class as white and pits an elusive ‘white working class’ against racialised minorities and immigrants, who are denied working class status, in a competition for scarce, deregulated and casualised employment and ever dwindling resources in neo-liberal Britain and America. Second, it constructs the ‘white working class’ as privileging their racial interests above class ones and as being racist, which results in the very stigma right-wing populist and libertarian advocates, who are themselves often part of the elites, falsely and opportunistically claim to oppose. Third, it normalises and mainstreams racism in both discourse and practice by portraying it as a popular demand, thus potentially fuelling hate crime. Finally, in addition to not addressing the inequality faced by ‘white’ working class people, it exacerbates the inequality and vulnerability faced by racialised and migrant working class peoples and actually serves establishment political and economic interests. The white working class revolt narrative mobilised by the populist far right and hyped by elite discourse (Glynos & Mondon 2016) has ignored not only elite driven racism (e.g. in politics, academia and the media), but also the more structural, institutional and systemic operation of racism in our societies. While those in positions of power (whether political or discursive) have often argued that they are merely responding to what ‘the people’ want, they have carefully ignored or downplayed the role they play as gate-keepers and shapers of public discourse and their proven influence as agenda-setters. Therefore, rather than ‘the people’ suddenly reverting to racist attitudes, we argue that it is the widespread and widely publicised acceptance, based on skewed evidence, that ‘the people’ has turned racist, that perversely led to the legitimisation of a racism as it began to be discussed as a popular feeling, rather than a construction fuelled by elite discourse.

UPDATE FOLLOWING THE 2020 US ELECTION:

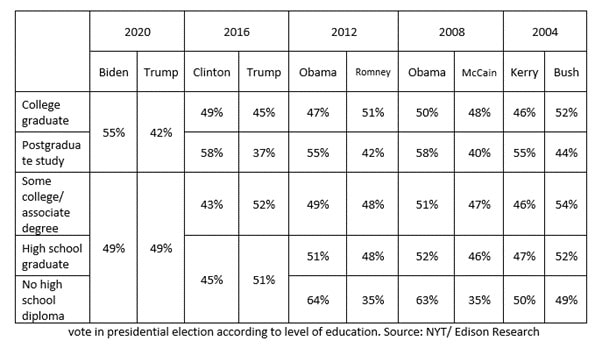

While it would be premature to draw full conclusions about the 2020 US election, we can already hear similar narratives to 2016 being pushed, hyping again the popular, ‘left-behind’ composition of Trump's vote. Yet, early exit polls seem to suggest that it is even harder to justify the ‘left behind’ narrative in 2020 than it was in 2016. It is worth noting that these are based on preliminary data that is likely to be refined over the coming days and weeks, but it is this data that is currently being used to push certain explanations of the vote, and for this reason, they are worth analysing in this context. In terms of education and, while we have less detail for now than in 2016, Joe Biden appears to have managed to appeal to those without college education more than Clinton had in 2020, but still remains behind Obama in these demographics, something which certainly helps Trump look better. However, Trump’s support in these categories appears to have shrunk. Of course, the higher turnout means that he may have kept his electorate there, but this would suggest then that the growth in his vote came from voters with higher degrees of qualifications.

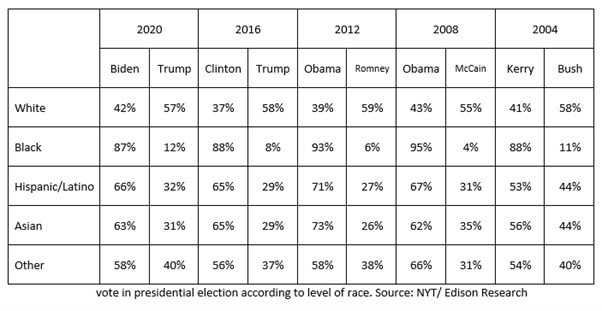

In terms of race, Biden seems to have performed better with white voters than Clinton and Obama in 2012. However, he seems to have lost votes within other communities compared to Obama in particular. Trump has only done marginally better with Latino and Asian voters and the bulk of his support remains white, the only category where he beats Biden.

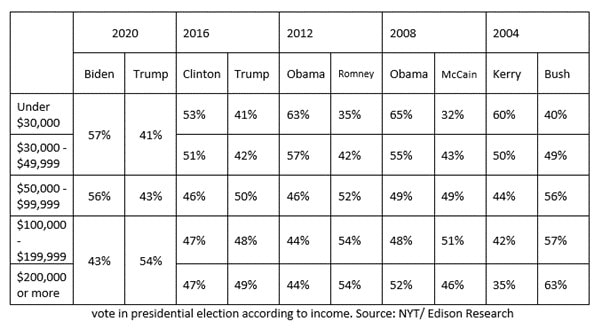

Finally, vote per income is the most fascinating at this stage, as it was in 2016. The narrative in 2016 and 2020, from both Trump’s supporters and opponents, is that his electorate is to be found in the ‘left behind’, who find themselves seduced by his populism and how he appears to respect and address them. While this already was inaccurate in 2016, it appears that Trump’s support base has mostly increased in the wealthier sections of the population, the very demographics he appealed most to, and more than Democrats in 2016 already. Interestingly, his support also seems to have fallen with the middle category of income.

This is of course basic opinion poll analysis based on preliminary data; there are many caveats and we would not claim that this is representative of public opinion. However, this still matters as it is the data that is used to construct narratives about the election and justify the appeal of leaders like Trump. Yet, as we can see, even this data does not support the more mainstream argument that Trump is indeed the leader of the revolt of the left behind. Stressing this is crucial not only to provide a more accurate picture of Trump’s support, but also to start to undermine the political and democratic legitimacy of reactionary politics which has falsely tied it to the plight of the working class and the people. More than ever, it is essential to reiterate that Trump’s interests and politics are not that of the many or those at the bottom, but squarely in favour of the elite, which he is himself a symbol of.

References:

Bhambra, G. 2017. Brexit, Trump, and ‘Methodological Whiteness’: On the Misrecognition of Race and Class. British Journal of Sociology: Special Issue on the Trump/Brexit Moment: Causes and Consequences 68: S214–S232. Emejulu, A. 2016. On the hideous whiteness of Brexit: 'Let us be honest about our past and our present if we truly seek to dismantle white supremacy'. Verso. Glynos, J. & A. Mondon. 2016. The political logic of populist hype: the case of right wing populism’s ‘meteoric rise’ and its relation to the status quo. Populismus working paper series no. 4. Mondon, A. 2017. Limiting democratic horizons to a nationalist reaction: populism, the radical right and the working class. Javnost/the public: Journal of the European Institute for Communication and Culture 24: 355-374. Mondon, A. & A. Winter. 2017. Articulations of Islamophobia: from the extreme to the mainstream? Ethnic and Racial Studies Review 40: 2151-2179. Nadeem, S., R. B. Horowitz, V. T. Chen, M. W. Hughley, J. Eastman & K. J. Cramer. 2017. Viewpoints: Whitewashing the Working Class. Contexts, June 23. Virdee, S. & B. McGeever. 2017. Racism, crisis, Brexit. In: Ethnic and Racial Studies: Race and Crisis Special Issue, edited by VIRDEE and GUPTA, 1802-1819. 41/10. Winter, A. 2017. Brexit and Trump: on Racism, the far right and violence. Institute for Policy Research (IPR) Blog, April 3.

Blog post by Aurelien Mondon, University of Bath, UK; and Aaron Winter, University of East London, UK

Blog first published 10 June 2019; updated 9 November 2020. Read the full article: Mondon, Aurelien & Winter, Aaron. Whiteness, populism and the racialisation of the working class in the United Kingdom and the United States. Identities: Global Studies in Culture and Power. DOI: 10.1080/1070289X.2018.1552440

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

|

Explore Identities at tandfonline.com/GIDE |

|

The views and opinions expressed on The Identities Blog are solely those of the original blog post authors, and not of the journal, Taylor & Francis Group or the University of Glasgow.