|

|

|

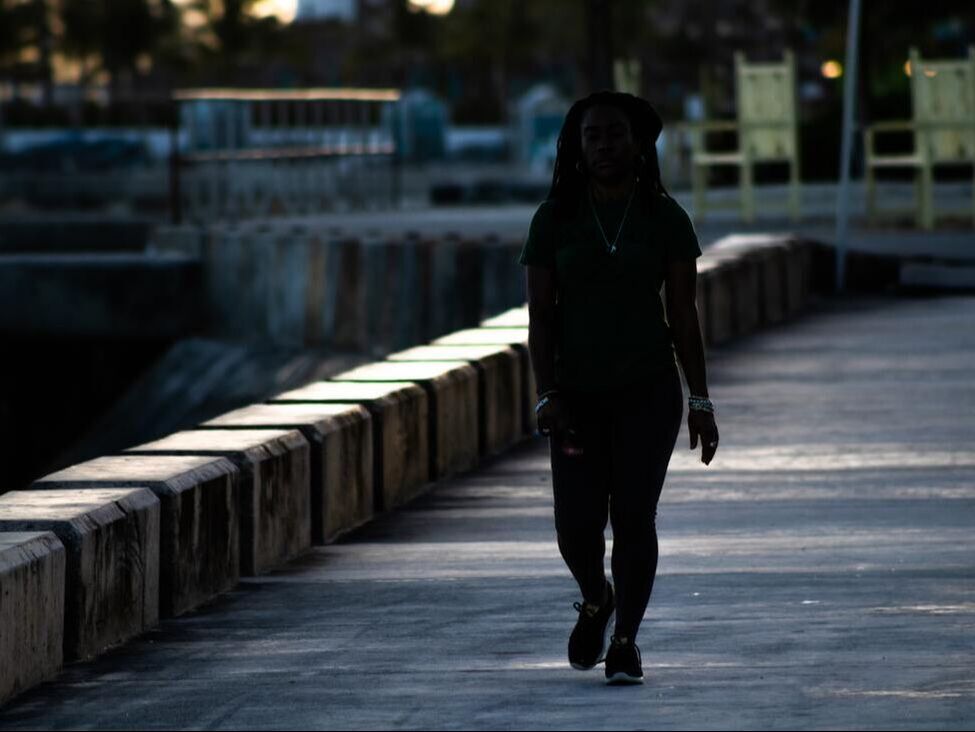

Blog post by Vadricka Etienne, University of Nevada, Reno, USA

Each year, my immigrant father embarks on a summer trip to Haiti. A lump jumps into my throat as he prepares for his journey. He’s excited to return home, but I fear for his safety. This fear grows yearly, and my anxiety spikes whenever he doesn’t answer the phone. My thoughts race to the worst-case scenarios, mainly because we’ve discussed what to do if he was kidnapped. While the rising gang violence demanded that he skip his trip last year, he would not miss another. I understand because he is at peace when in Haiti. But I find myself taking deeper breaths only when he lands in Miami, making his way home. During the summer, I consumed conflicting media reports. Mainstream media catastrophized the gang terror, while Haitian content creators shared the mundane, such as dinners out on the town, demonstrating that the violence was not everywhere in the county. These contradictions encapsulate how the children of immigrants could have a fragile relationship with their parents’ birthplace as they often experience the country through the lens of others, very rarely their own.

0 Comments

One glimpse at minority language protection: the fine line between empowering and segregating24/5/2023

On 5 November 2022, the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages celebrated its 30th anniversary. This charter lays down the principles for protection and promotion of minority languages and their use in education, cultural life, public services, and other sectors within the EU. Undoubtedly, such supra-national and similar national policies generally improve the rights and lives of minority members.

My Identities article, ‘Drifting borders, anchored community: re-reading narratives in the semiotic landscape with ethnic Lithuanians living at the Polish borderland’, discusses a concrete example of one such minority protected on national and supra-national levels – the national Lithuanian minority in Poland. I provide a glimpse into the realities of its members’ language use, identification and narratives of belonging. I learned that they find some official minority protection attempts more concerning than helpful.

What does a Thai person look like? How do expectations about citizenship create an ethicized cultural phenotype? In our Identities article, ‘Turbaned northern Thai-ness: selective transnationalism, situational ethnicity and local cultural intimacy among Chiang Mai Punjabis’, we explore family histories, selective transnationalism and regional Lanna identities among Thai citizens with Punjabi heritage and selective cultural identity. This article argues that Punjabi Thais maintain their networks and cultural connections with a historic ancestral homeland, but they also cultivate forms of local cultural intimacy in ways which leapfrog the linguistic and cultural hegemony of Thai national identity. In other words, despite their non-Thai appearance, these Punjabi Thais have deeply local cultural knowledge, speak Northern Thai language fluently and have Northern Thai cultural sensibilities.

In 2018, the research department of Awel, a Flemish civil society organization, published a report on the impact of the late terrorist attacks in Europe on the identity formation of minority youth. The report, based on testimonials, revealed that some Muslim children try to hide their ethno-religious background out of fear of being verbally attacked. Some even wish to ‘unbecome’ Moroccan or Muslim to respond to Islamophobia.

The largest ethnic minority group in Belgium originates from Morocco. This primarily Muslim group is indeed strongly stigmatized, even more so since 9/11. It is argued that terrorist attacks increase Islamophobic or anti-Muslim sentiments, which hence also impacts the well-being of Muslim children living in Flanders. The findings of the research report nevertheless did not receive as much public and political attention as deserved. Yet, ethnic minority citizens’ identity formation has long been a subject of political interest, especially since many politicians across the spectrum propose that minorities, and particularly Muslims, do not identify as Belgian.

Young people in ethnically divided post-conflict societies are often happy to date across ethnic lines, notwithstanding its prevailing discouragement. My recently published Identities article, 'Kiss don't tell: attitudes towards inter-ethnic dating and contact with the Other in Bosnia-Herzegovina', examines this in Bosnia-Herzegovina, which it takes as a typical case of an ethnically divided post-conflict society: young people struggle to meet other ethnic groups due to the high levels of segregation in society. Such contact is also discouraged in the home, in schools, in religious institutions and in the media. I use focus groups conducted on Facebook and follow-up interviews to speak to young people across the country who date across ethnic lines despite these obstacles.

In the comedy special ‘His Dark Material’, Jimmy Carr joked about the Roma Holocaust:

‘When people talk about the Holocaust, they talk about the tragedy and horror of 6 million Jewish lives being lost to the Nazi war machine. But they never mention the thousands of Gypsies that were killed by the Nazis. No one ever wants to talk about that, because no one ever wants to talk about the positives.’

Carr’s joke has sparked widespread outrage – yet some voices have defended it as ‘gallows humour’. Back in 2017, the author Alexandra Erin, in a Twitter thread on comedy, wrote ‘If the person on the gallows makes a grim joke, that’s gallows humor. If someone in the crowd makes a joke, that’s part of the execution.’ And here, Carr wasn’t speaking from the gallows; those on the gallows are in fact, one of the most oppressed and discriminated against groups to this day: the Roma, and within the scope of the joke, the European Roma and Sinti targeted in the Holocaust.

On 24 September 2016, the National Museum of African American History and Culture opened on the National Mall in Washington, D.C. to commemorate the contributions and experiences of people of African descent to the United States. Engraved on one of the walls of the museum reads, ‘I, too, sing America’. These four words are quoted from African American poet Langston Hughes’ poem of the same name. Written in 1926, Hughes’ poem reveals the experiences of African Americans during Jim Crow America. As Hughes poetically writes,

'I, too, sing America.

- Langston Hughes, ‘I, too, am America’, from The Collected Poems of Langston Hughes

In the wake of Colombia’s national branding as a pluri-ethnic nation, on the one hand, and of Black and Indigenous social movements denouncing racism, ethno-racial inequality, systemic necropolitics (Mbembe, 2003; Alves, 2014) and social injustice, on the other hand, Bogotá’s municipal ‘multicultural turn’ in the 2010s seemed a precious opportunity to partly reconcile the ambivalent reality of Colombia’s multiculturalism, torn as it is between the pluri-ethnic reality of its social constituencies and the simultaneous inclusion (often as commodification) and exclusion (racialisation) of its ethnic minorities.

In particular, the latest POT (Plan de Ordenamiento Territorial, or Land Use Planning) — that determines urban growth in Bogotá for a span of at least 15 years — and its first Ethnic Focus (or Ethnic Approach; Enfoque Étnico Diferencial, in Spanish) in the late 2010s, could have been an opportunity to develop an understanding of urban dynamics informed by ‘race’ and racism, whereby patterns of racialisation and antiblackness in the space of the city could be finally and formally acknowledged by the public administration and Colombian urban professionals (planners, architects, land economists, geographers, urban sociologists, etc.) — for the majority of whom urban inequality has long been conceived as a socioeconomic matter devoid of any racial inflection. However, as elsewhere in Latin America, the municipal ‘multicultural turn’ in Bogotá largely missed that opportunity. In my Identities article, ‘The governmentality of multiculturalism: from national pluri-ethnicity to urban cosmopolitanism in Bogotá’, I detail the ambiguities inherent to Colombia’s pluri-ethnic turn at the urban scale, from a situated perspective on its capital city, Bogotá: inclusive and plural in its narrative and for which concerns the extraction of value from ‘ethnic presence’ in the city, but exclusive and tailored at regulating (constraining) ‘diversity’ through its policies and planning practices.

Cross-posted from RACE.ED

It has been widely reported that the COVID-19 pandemic has disproportionately impacted Black and Ethnic Minority (BAME) communities across the UK, which have suffered higher rates of hospitalisation and mortality. While the causes of this outsized impact are yet to be fully untangled, it is consistent with longstanding disparities in health outcomes and access to medical treatment between BAME communities and the white majority. The pandemic has, in effect, brought pre-existing health inequities to the fore. With all our hopes for overcoming the pandemic resting on the success of our vaccination programme, it is essential that the jabs being put into arms have been shown to be safe and effective for people across the entire spectrum of our ethnically diverse population. This is important for two reasons. First, medical treatments can have varying effects for people of different ethnic backgrounds, and hence it is essential that clinical trials include volunteers that are representative of the different groups that make up our population. Second, people from BAME backgrounds deserve the same opportunity to build trust in vaccines. This means knowing that vaccines have been rigorously tested on volunteers from their own communities, as well as other groups.

In the early 2010s, France repatriated a large number of Roma back to Romania, following a series of highly controversial reforms by Nicholas Sarkozy’s government (BBC, 2010). Campaigners for human rights, free movement, and workers’ rights hotly contested those harsh actions of forced repatriation, which were widely discussed in international media. A Romanian article called ‘Back to the life of Gypsy in Romania’ (Micu, 2010) suggested that most of the transnational worker Roma went back to their homelands in the rural part of southwestern Romania. Taking an insight into this particular Romanian area, our recent study in Identities: Global Studies on Culture and Power explores perceptions of Roma people amongst the non-Roma community and how the Roma people respond to these perceptions today (Creţan, Covaci and Jucu, 2021).

To understand the social position of the Roma community in Romania, it is necessary to take a step back in history. Following the fall of communism, Eastern and Central European passed through a series of massive social and economic transformations. The area we explored in our study is on the border of Romania and Serbia and has traditionally been multicultural and multi-ethnic. However, it is also the site of long-term marginalization for the Roma communities. The shift towards a capitalist economy has exacerbated their ‘othering’, since the new economy offers the Roma few possibilities. Consequently, many joined the new transnational labour force in Europe, working abroad as seasonal labourers (including those targeted by Sarkozy in France). Others chose to leave behind their traditional skills and assimilate into majority society. The loss of guaranteed work which the Roma had under the communist regime has tended to intensify the post-communist direct discrimination against Roma, since they are often stigmatized as unemployed and dependent on public welfare.

Arab Americans have been categorised as White on official government forms for several decades, which grossly misrepresents this population. Advocacy groups unsuccessfully fought during both the Obama and Trump administrations to have the ethnicity category expanded in the 2020 Census. The ramifications of this community remaining uncounted include lack of funding for social, education, and health care services and less leverage in political issues. Along with negating the incredible diversity within this group, such categorisation excludes Arab Americans from affirmative action programmes.

The recognition of this ethnic group on government forms would allow for their inclusion in such programmes, which is crucial given the prominence of discrimination in the US. However, the irony lies in how mainstream society tends to change their view depending on current events. When there are no crises involving Arabs around the world, Arab Americans are seen as White. However, when a crisis does occur involving Arabs – as either transgressors or victims (i.e. 9/11, invasion of Iraq) – they will be gazed upon as ‘Other’ and enemies of America. The rise in hate crimes against Arab Americans – and anyone who fit into the public’s notions of what an Arab or Muslim looks like – following the terrorist attacks of 9/11 is a prime example of this phenomenon. Consequently, regardless of being labeled as White, Arab Americans have experienced discrimination similar to other racially visible minority groups. This begs the question: if they are recognised as White, then why are they treated as ‘Other’?

It is well known that Asian American men are commonly stereotyped as effeminate, asexual and nerdy in American society. But how are such dominant stereotypes experienced by them, and how do they negotiate, avoid and contest them? In my Identities article, ‘What makes hegemonic masculinity so hegemonic? Japanese American men and masculine aspirations’, I demonstrate how Asian American men appear to be emasculated in such a manner because they are compared to idealised, hegemonic images of masculinity usually associated with white men.

Because such hegemonic masculine standards have become pervasive and widely accepted in American society, they have also been adopted by Japanese American men. As a result, they perceive their subordinate masculinity as inferior and effeminate, making them feel romantically unattractive. Such negative assessments are shared by Japanese American women, who are also under the pervasive influence of hegemonic masculinity and often find Japanese American men to be romantically undesirable, and prefer to date and marry white men.

The fact that some second-generation immigrants were involved in the brutal terror attacks in major European cities such as in Paris in 2015 and Brussels and Munich in 2016 exacerbated xenophobia among politicians and the broad public. These terrible incidents increased scholarly interest in the integration of second-generation immigrants further, and heightened anti-immigrant and anti-Islamic sentiments across Europe and far-right.

In addition to the terror attacks, economic restructuring and growing poverty amongst the working-class have also resulted in the rise of far-right in Germany. This has become visible with the Patriotic Europeans against the Islamisation of the West (PEGIDA) movement and strengthening of the Alternative For Germany (AFD). In this regard, the host society often tends to relate the Turkish second generation's social and economic disintegration to marginalisation and ‘Islamisation’. In such a context, studying the stigmatisation of ethnic minorities and immigrant groups reveals discrimination, stratification and ethnic boundaries. Along similar lines, the destigmatisation strategies of minorities, how they respond to the majority to maintain their dignity, achieve recognition and invest in their integration, are equally revealing. My Identities article, 'Disadvantaged, but morally superior: ethnic boundary making strategies of second-generation Turkish immigrant youth in Germany', examines how social, political and structural changes in Germany increase anti-Muslim, anti-immigrant and anti-refugee sentiments. By drawing on in-depth interviews and ethnographic data with twenty second-generation Turkish immigrant youth, the article reveals the kind of stigmatisations Turkish immigrants (the largest Muslim group) face, and, more importantly, how they deal with these stigmatisations in their daily lives.

Ken Carter, whose character inspired the realisation of the inspirational 2005 basketball movie, Coach Carter, decided to end the 1999 undefeated streak of Richmond High School basketball team because of his players' poor academic performance. His decision to lock the school gym and cancel the upcoming basketball matches, despite opposition amongst the Richmond community, garnered enormous US media attention framing it as an elevation of education over sports. While extensively elaborating and rationalising the gym shut-down in front of his students, Coach Carter posed a rhetorical question that resonates amongst recent events of police brutality and racial injustice in the US: where do these students end up after graduating high school? The answer for those who do not make it to college or into a professional sports career is, for many, probably prison.

Even though the US imprisonment rates have recently experienced its most significant decline in the last two decades, the Bureau of Justice Statistics (2018) data indicate that the US prison population's racial and ethnic makeup remains highly disproportionate to the actual demographics in the country. According to the US Justice Department, black Americans represent 33% of the sentenced prison population – a number nearly triple the 12% share of their US adult population. Even though the racial margin of incarceration has been in decline, black Americans constitute two times the rate of imprisoned Hispanics and slightly above five times the rate of imprisoned whites in the United States. Automatic transmission: how cars help us understand the dynamics of race and racialisation16/12/2020

In my Identities article, ‘Automatic transmission: ethnicity, racialization and the car’, I discussed how various types of racism can be transmitted through cars and roads, and feed into driver behaviour. While this can result in racial discrimination operating in formal and legal contexts, such as policing, racialisation through cars has a much broader, and at times, arguably banal, normative and taken for granted presence and reach.

In ethnically diverse towns and cities in the UK, when expensive cars are driven by young non-white males, what appears to be ordinary (driving and cars) becomes subject to racialised logic – that certain behaviours are tied to what become normative expectations of the ethnic group in question. In part, this happens because of what cars do and do not signify, but also, of course, this hinges on existing codes, stereotypes and ways of perceiving and explaining the idea of race, and all that flows from it. Earlier in 2020, we learnt that a number of prominent Black Britons, including MP Dawn Butler, had experienced, and subsequently spoke out about, racist policing. As distressing as such events are they are not particularly unusual; every day, black bodies are subject to similar, and worse, attention from law enforcement. In some cases, of course, the police may well have legitimate grounds to pull over a suspect, but often, it is the marker of race that helps prompt or even provoke the intervention.

The places in which people contest and negotiate cultural diversity are themselves meaningful. Places hold cultures, histories and memories, and shape people’s interactions. A suburb of a city is one such place.

In our Identities article, ‘Making a place in Footscray: everyday multiculturalism, ethnic hubs and segmented geography’, we explore the meaning and experiences of cultural diversity in Footscray, a suburb of Melbourne, Australia. We interviewed both residents of Footscray and others who had close connections to the suburb about their everyday experiences in the suburb, particularly around cultural diversity. Footscray is culturally diverse, both in terms of the number of people born outside of Australia and the range of nations from which people have migrated. While racism and racialisation form part of the dynamics of the suburb, Footscray, on the whole, is a place in which people embrace cultural diversity, and everyday diversity has come to be a defining feature of the suburb. COVID-19, BAME communities and local football: can local BAME football win against COVID-19?16/9/2020

On 26 May 2020, professional football in England resumed after a three-month shutdown in response to the COVID-19 outbreak in the UK. The disproportionately high COVID-19-related mortality rates among Britain’s black, Asian and minority ethnic (BAME) communities prompted some debate among football professionals, journalists and academics as to the potential higher risk ‘project restart’ posed for black professional footballers compared to their white peers (Minhas et al, 2020). Nonetheless, the launch commenced, and fears were alleviated (initially at least) by the implementation of a robust test, track and trace system and by clubs operating extraordinarily high levels of surveillance and control over their players’ daily activities.

On 12 September, the Football Association in England (FA) ‘restarted’ the non-professional format of the game. By comparison, there has been much less public scrutiny of this roll-out, and especially in relation to broader questions around public health. Or to the potential of local football to contribute to the disproportionately high COVID-19 mortality rates among Britain’s minority ethnic communities. The absence of debate is quite remarkable given that, according to the FA, there are currently over 3,000 non-professional women’s, men’s, youth and mini-soccer football clubs that play on a ‘Saturday’ across England, compared to just 92 professional clubs. This is also surprising given the long history and relationship between local football and Britain’s BAME communities.

According to the 2000 census in China, 3.23 percent of married citizens are in an interethnic marriage, and 12 of the 56 officially recognised ethnic groups have an intermarriage rate higher than 50 percent, meaning more than half of married people in these 12 ethnic groups are in an interethnic marriage.

While these statistics suggest that the multiethnic population is not small in China, multiethnic identity options are not officially available in China. All Chinese citizens are registered at birth by their parents with only one official ethnic category, which must be the same as at least one of their parents. This exclusive ethnic identity is presented on the person’s ID card, largely influences their life chances in a wide range of domains, and can hardly be changed. How do people with mixed ethnic backgrounds deal with the limited and exclusive identity choices? Compared to the debates and social movements in western countries, why is the topic of multiethnic identity seldom brought up in China? In my Identities article, 'Official classification, affirmative action, and self-identification: Hui-Han biethnic college students in China', I focus on a specific group of people in China who have multiethnic backgrounds – college students who have a Han parent and a Hui parent – and examine how they understand their ethnic identity. Han is the majority ethnic group that constitutes 91.5 percent of the national population. Hui is the fourth largest ethnic group, the largest Muslim group, and the most geographically dispersed minority ethnic group in China. Using interviews with 20 respondents, I investigate whether this group of people experience any discrepancy between their multiethnic backgrounds and their official, single ethnicity, and what their attitudes are towards institutionalising multiethnic identities.

A key scene in Danis Tanović’s Academy Award-winning film No Man’s Land (2001) features two soldiers, a Bosnian Muslim (a Bosniak) and a Bosnian Serb, who have gotten stuck in a trench during the 1990s Bosnian War. In their joint effort to escape from this unfortunate situation, they draw closer; they talk about their prewar lives and recognise that they have many things in common, even some common acquaintances. However, it comes as no surprise when, in the firestorm of bombshells, the question arises of who is responsible for the destruction of Yugoslavia, of their lives as they were before the murder and devastation. The two soldiers start to swap accusations until the armed Bosniak points his weapon at his opponent and asks one last time: ‘Who started the war?’

Around the world, conflicting parties engage in self-exculpation and self-victimisation – from Bosnia-Herzegovina to Sri Lanka, from Northern Ireland to South Africa, not to mention the Middle East. Denying one’s own responsibility and guilt and the fight over one’s own victim status seems to be a constitutive part of many conflicts and postwar situations. As socio-psychological and sociological research show, self-victimisation is accompanied by several advantages. It not only contributes to a stabilisation of group boundaries by fostering internal cohesion and outward demarcation, but also promotes feelings of moral superiority. Hence, self-victimisation is politically beneficial and a suitable tool for protecting one’s own we-ideal and with it one’s own I-ideal in the context of collective violence. It is the chosen mean to restore those facets of identity, which have potentially been corrupted or injured by the collective violence. But what happens when people are confronted with conflicting perspectives of reality, with perspectives according to which the respective ethnic in-group is not to be considered only as victim of war but also – or even exclusively – as perpetrator? Second-generation Central Americans and the formation of an ethnoracial identity in Los Angeles15/4/2020

Over 20 million immigrants from Latin America and the Spanish-speaking Caribbean arrived in the United States as part of the post-1965 immigration wave. Certainly, this migration wave had important and lasting demographic impacts in the US; in particular, it contributed to the significant growth of the Latino population. At 59 million, Latinos are the largest minority group in the US and they are projected to reach a quarter of the US population over the next few decades.

While Mexican immigrants have dominated migration flows from Latin America, Central American immigrants and their children are an important component of the post-1965 immigration wave. Central Americans arrived in the US in significant numbers during the 1980s and 1990s as a result of civil wars, political repression, economic instability and destruction caused by natural disasters in Central American countries. Today, Central Americans constitute the third largest Latino group in the US; moreover, the children of Central American immigrants who arrived during 1980s and 1990s have entered adulthood.

In our Identities article, 'Digital institutions: the case of ethnic websites in the Netherlands', we conceptualised websites as digital institutions. Since the concept of institutions appears to be fuzzy, comprising formal and informal as well as micro and macro organisations, we argued that they, although socially embedded and culturally loaded, conceptually are insufficient to highlight their specificity. In order to specify the institution, we employ the concept of script, defined as recurrent activities and patterns of interaction. Empirically, we apply this concept to detail ethnic websites in the Dutch Hindustani community and to highlight what needs they fulfil for its visitors and in the Hindustani community. We argued that these ethnic websites fulfil a wide range of needs — notably, as a means of communication, a platform on which community members can address ethnic issues, a device through which to build networks, and a place from which to download material — thus fostering the identity of the ethnic group. Since evidence based on one community may be a matter of happenstance, we substantiate our argument with a comparison of ethnic websites from the younger generation of white Dutch, Hindustanis and Moroccans in the Netherlands.

Patronato is a well-known commercial neighbourhood in Santiago, Chile with a tradition of migrants’ settlement and entrepreneurship that dates back to the nineteenth century. Today, the area is branded as a textile and vibrant ‘multicultural commercial neighbourhood’, as read in several street signs. Traders and workers’ ancestries include Chilean, Korean, Chinese, Indian, Peruvian, Palestinian, Syrian, Haitian, Colombia and Venezuelan, among many others. Yet, despite its growing diversity, Patronato is often described (in the media, films and popular narratives) as a Palestinian-Korean neighbourhood.

In our Identities article, ‘Contested and interdependent appropriation of space in a multicultural commercial neighbourhood of Santiago, Chile’, we analyse memories, images and uses of space by entrepreneurs of Korean and Palestinian ancestry, as well as their competing and reciprocal appropriation of space. Through processes of social production and construction of space (Low 2017), we examine their experiences of making, inhabiting and appropriating space, in relation to the transformations of the political economy.

‘Hong Konger is not a race; it’s a spirit’, claimed a group of ethnic minority advocates of protests against the now-shelved extradition bill and anti-mask law in Hong Kong. The dissociation of Hong Kong identity from race marks the blurring of cultural boundaries between those who are racially Chinese and those who are not. Hong Kong’s political climate appears to play a prominent role in forging a collective identity.

Such an identity claim reflects ethnic minorities’ fulfilled desire to be recognised as Hong Konger like the rest of local Chinese people. My co-authored Identities article with Sivanes Phillipson, 'Bordering on sociocultural boundaries and diversity: negotiating Filipino identities in a Hong Kong multi-ethnic school', presents a relevant scenario in an education setting that speaks to the identity tensions amongst minority groups.

Boxing fans and pundits might be familiar with the term 'undisputed' champion. Reserved mainly for boxers, the 'undisputed' champion is seen as the unquestioned champion of (mainly his) weight division. To achieve this status, he must become champion of the various worldwide boxing organisations. Of course, the boxer must constantly defend this status over and over again in order to maintain his place atop the boxing hierarchy. In other words, being an undisputed champion is fleeting, unpredictable, and always in flux.

In my Identities article, ‘Undisputed’ racialised masculinities: boxing fandom, identity, and the cultural politics of masculinity', the term 'undisputed' is repurposed to theorise and allegorise how it is fraught with contradictions. My findings highlight how the undisputed status of racialised masculinity is constantly struggled over, negotiated and contested by male boxing fans of colour. Based on fieldwork observations during a Manny 'Pac-Man' Pacquiao vs. Juan Manuel Marquez boxing match in 2011, interviews conducted with 1.5 and 2nd generation Filipina/o Americans, and close analysis of 'Gayweather,' it analyses how male fans of colour seek an undisputed masculinity in complex and problematic ways.

Haymarket/Chinatown is a precinct located in the southern end of Sydney’s Central Business District. The precinct has become part of the City of Villages initiative, promoted by the City of Sydney administration to inject dynamism in the local economy based on the belief that the city is made up of diverse marketable areas, each endowed with a unique identity. Unlike the other precincts in the Inner Sydney area, the point of differentiation chosen for Haymarket/Chinatown is ‘ethnicity’ — more precisely, an ambiguous multi-Asianness within which images of Chinese communitarian identity occasionally emerge to confer a sense of authenticity to the ethnic place brand.

In my Identities article, ‘Ethnic community in the time of urban branding’, I observe how these simplified images of ‘groupist’ (Brubaker 2002) Chinese identity emerge from the brand management strategy for the Haymarket/Chinatown precinct despite the diversity of the local business and resident community. I frame these instances as tensions inherent in the process of place branding, which is characterised by the need to essentialise for marketing purposes while grappling with increasing levels of cultural complexity of the most populous Australian city. |

|

Explore Identities at tandfonline.com/GIDE |

|

The views and opinions expressed on The Identities Blog are solely those of the original blog post authors, and not of the journal, Taylor & Francis Group or the University of Glasgow.