|

|

|

Blog post by Aaron Winter, Lancaster University, and Co-Editor, Identities: Global Studies in Culture and Power. Cross-posted from openDemocracy.

Since the horrific Hamas attack in Israel on 7 October and Israel’s assault on Gaza in response, I have heard a great deal about how Jewish people in Britain, as well as other places, are intimidated, afraid and under threat. According to Justin Cohen of The Jewish News, “the Jewish community at the moment is full of dread, full of fear, like I've never seen before”. According to the Campaign Against Antisemitism, British Jews felt “forced to hide” during “anti-Israel” protests in London. Havering Council in London even cancelled its annual Hanukkah menorah display out of fears it could “inflame tensions”, though subsequently reversed the decision. We have also seen similar cancellations in the US.

Blog post by Aaron Winter, Lancaster University, and Co-Editor, Identities: Global Studies in Culture and Power. Cross-posted from British International Studies Association Voices from BoisMitidja.

This piece is based on my intervention at the British International Studies Association (BISA) Colonial, Postcolonial and Decolonial (CPD) event ‘Refusing Carcerality - A Public Roundtable’ at King’s College London on 14 June 2023. It was a great event and opportunity to hear other interventions, reflect on issues, and bring together some issues and ideas I have had working in Criminology and on counterextremism, counterterrorism and the far right in relation to important discussions about carcerality and abolition. Carcerality always extends beyond what are typically seen as carceral institutions, policies and punishments, particularly in the context of abolitionist theory and activism and our understanding of the carceral state and society. I would like to return it to the prison and penal system for a moment though to discuss how differences and alternatives to the carceral are constructed, used and played off one another in the context of counterextremism, counterterrorism and Criminology in ways that can distract from and ultimately serve an unequal and unjust system. This is particularly important if our opposition to the carceral is also about opposing this system, focusing on systemic inequalities and injustices (related to but expanding beyond ‘crime’) and envisioning more radical and truly emancipatory alternatives.

On 7 March 2023, UK Home Secretary Suella Braverman, escalating the rhetoric on and punitive approach to migration, asylum and refugees, announced the ‘Illegal Migration Bill’ and strategy to stop migrants crossing the Channel in small boats by arresting, detaining, deporting and banning those caught. In response, former football player and BBC Match of the Day (MOTD) Presenter Gary Lineker tweeted that it is ‘an immeasurably cruel policy directed at the most vulnerable people in language that is not dissimilar to that used by Germany in the 30s’. The tweet led to a backlash in which responses ranged from the claim that he was operating beyond his remit as a sport presenter (as if they have not had to discuss racism and nationalism before), that he was in breach of the BBC’s impartiality rules, and that the comparison was unhelpful. Keir Starmer, Leader of the opposition Labour Party stated: ‘I think comparisons with Germany in the 1930s aren’t always the best way to make one’s argument’. Others took offense and expressed shock that anyone could associate Britain and the current government with the lead up and precursors to Nazism and the Holocaust. Some claimed that Lineker actually referred to these explicitly in his tweet, which he did not. Former Conservative MP for Stoke-on-Trent Jonathan Gullis claimed that Lineker was calling ‘people up here’, referring to Northern ‘Red Wall’ voters, which Starmer and Labour are also targeting with anti-immigration rhetoric, ‘racist bigots, Nazis’. According to Matthew Goodwin, Lineker’s comments are an example of how out of touch the ‘new elite are from the majority of the ‘people’ from the ‘Red Wall’ to ‘Tory Shires’, and particularly those at ‘the bottom’: ‘the white working class, straight men, non-graduates, and those who cling to more traditionalist views, such as supporting Brexit’.

While the ‘Common-Sense Group’ of MPs and Lords still retain the term, during the last few years the far-right conspiracy theory Cultural Marxism has fallen out of favour within mainstream British right-wing discourses. It has been largely superseded by the pejorative use of the term ‘woke’, which originated from the fight for racial justice in the USA. This blog post examines the transition from Cultural Marxism to woke and asks what does the derogatory use of so called ‘wokeism’ offer to its patrons that Cultural Marxism doesn’t?

Cultural Marxism is a long-standing far-right conspiracy theory. According to the American far-right, The Frankfurt School of Jewish Marxist intellectuals, who escaped Nazi Germany, initiated a plan to destabilise America from within by using their supposed control of the organs of culture, including education, the media, and churches, to attack Western civilisation and undermine pride in its past. The far-right sees the progressive civic and social movements that began in the 1960s – feminism, LGTBQ+ rights, black power, anti-colonial liberation, environmentalism, and pacifism as part of Cultural Marxism’s orchestrated effort to “destroy the American way of life as established by whites”.

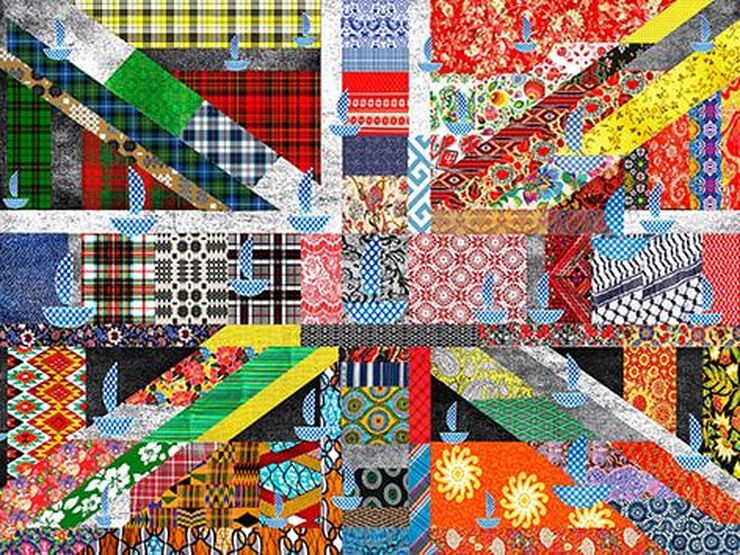

Patriotism is having a moment. From French President Emmanuel Macron’s claim that patriotism is ‘the exact opposite of nationalism’ to UK Labour Party leader Keir Starmer’s call for party members to be ‘proud of being patriotic’, centrist and progressive politicians are appealing to patriotism as a bulwark against the rise of right-wing nationalism. In the US, a July 2021 YouGov poll found that sixty-nine percent of respondents believed that a person could be considered patriotic while participating in a protest for racial equality.

These examples stand in contrast to other recent appeals to patriotism: an ultranationalist French political party established in 2017 took the name ‘Les Patriotes’. The Tory government has spent £163,000 on Union flags in the past two years, and has lent its support to the ‘patriotic’ One Britain One Nation campaign. And the same July 2021 YouGov poll in the US found that sixty percent of Republicans considered themselves ‘very patriotic’ – compared to only twenty-four percent of Democrats. Why is patriotism so appealing across the political spectrum? And what does this mean for the prospects of ‘progressive’ patriotism? My Identities article, ‘‘The opposite of nationalism’?: rethinking patriotism in US political discourse’, considers the multiple and contradictory – but always exclusionary – ways that patriotism has been used by politicians across the US political spectrum. Politicians of all stripes, I find, describe themselves and their supporters as patriots. Although few define the term explicitly, all frame patriotism as an implicitly positive love for one’s country. I argue that this vagueness allows politicians to position their policy agendas, and their own character, as ‘authentically’ American. Crucially, it also permits them to position their opponents as unpatriotic and, by extension, un-American. This sharpens any attacks on a politician’s opponent; even more dangerously, it hardens the borders between those who belong to the nation and those who do not. For non-citizens, migrants and racially minoritised people, appeals to patriotism bring exclusion and violence.

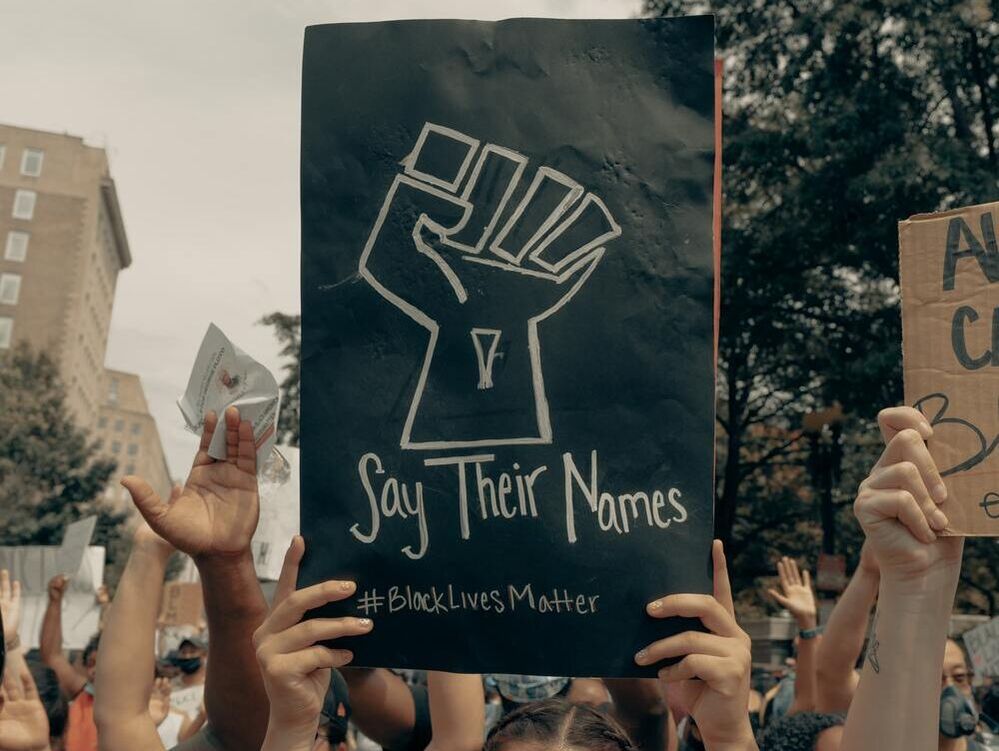

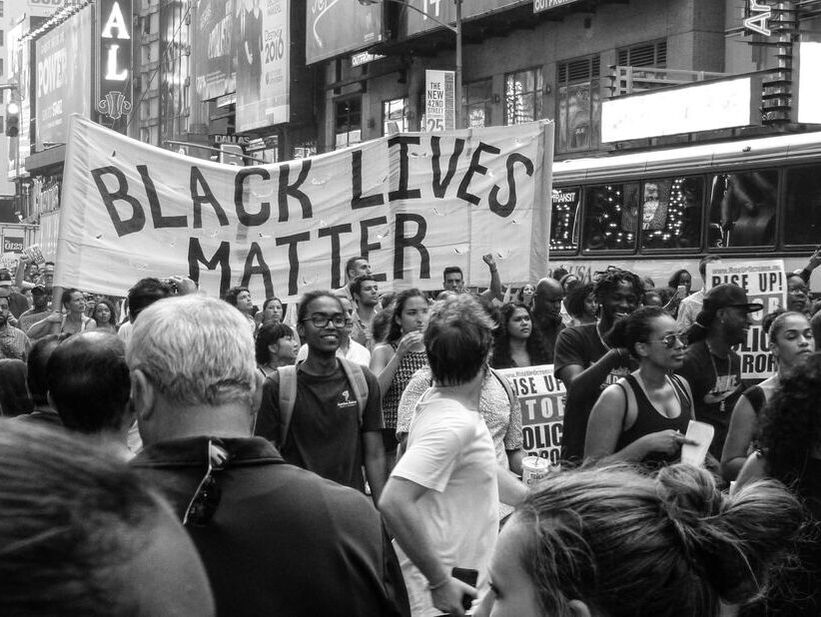

The murder of George Floyd in the spring of 2020 sparked an outcry against police brutality and racial injustice in the United States. In the wake of the killing, support for the Black Lives Matter movement rose sharply among white Americans. Shows of support ranged from the (controversial) posting of blacked-out photos on Facebook and Instagram, to patronage of black-owned businesses, to marching in BLM protests.

We are now more than a year out from George Floyd’s killing. Much of the antiracist fervour expressed by progressive white Americans in 2020 appears to have fizzled. According to a Politico/Morning Consult poll, the percentage of white Americans with positive evaluations of the Black Lives Matter movement has declined significantly since last summer. Some see this change as an indication of the superficiality of many white Americans’ involvement in antiracism. While this may be true, our Identities article, 'Racemaking in New Orleans: racial boundary construction among ideologically diverse college students', points to the important role of racial boundary construction in limiting white Americans’ involvement in antiracist efforts.

Cross-posted from Georgetown Journal of International Affairs.

Recent events in France have revealed how race remains such a loaded concept in French society. But policymakers must emphasize that this is nothing new, and that public policies need to address historical and present racism in France in order to move forward. Events in recent months have once again made race and racism part of public debate in France. There was the beheading of school teacher Samuel Paty in a banlieue, or suburban outskirt, north of Paris in October 2020. Then the beating, captured on video, of Michel Zecler, a forty-one-year-old Black music producer, by four police officers last November in Paris. These debates have even included accusations of importing Anglo-American or US conceptions of race and racism to the French context, as evident in a recent interview with President Emmanuel Macron in the New York Times and movement by his administration to investigate French universities for importing American theories. This is in addition to a proposed bill making it a criminal offense to share images of police officers on social media platforms, amid a growing mobilization against police violence targeting Black and Maghrébin-origin individuals.

In the aftermath of the 2016 attempted coup against the Erdoğan government in Turkey, several hundred Turkish-Dutch citizens took to the streets in the Netherlands. Some protesters harassed a journalist documenting the protests. Prime Minister Mark Rutte responded by telling the demonstrators to ‘piss off to Turkey’. This statement exemplifies how Turkish-Dutch citizens, born and raised in the Netherlands, can be scrutinised and quizzed about their loyalty and the extent of their integration. When they express deviant behaviour or political views in the eyes of the majority, they are considered ‘Turks’ or ‘Muslims’ only, which is not reconcilable with being ‘Dutch’. Politicians often understand Dutchness in a culturalised way, in which progressive ideals such as gender equality, sexual liberty and democracy are considered to be important signifiers of Dutchness. This frame creates a contrast between progressive ‘natives’ and ethnic minority citizens, who are othered as backwards, not sharing these progressive values.

How do Turkish-Dutch Muslim young adults deal with such stigmatisation? This is the question we raise in our Identities article, ‘Claiming the right to belong: de-stigmatisation strategies among Turkish-Dutch Muslims’. Investigating de-stigmatisation strategies by Turkish-Dutch youngsters contributes to understanding processes of belonging, social inequality and ethnic boundary-making. Stigmatised individuals can contest and rephrase their position, bringing about social change and upsetting existing social categories. To explore de-stigmatisation, we interviewed 25 Turkish-Dutch, Muslim young adults and conducted ethnographic observations in two youth groups.

Following George Floyd's horrific death and the scenes of his sensational courtroom trial which played out to public scrutiny across the world, my recently published Identities article, 'The dying Black body in repeat mode: the Black 'horrific' on a loop', addresses the notion of the recurrence of 'Black death' in repeat mode offline and its viral circulation online in the digital economy.

Digital platforms abstract dead bodies as floating matter to be consumed without context. In tandem, this 'repeat mode' produces a visuality or a 'shadow archive' to showcase Black bodies as perpetually given over to brutality, violence and foreshadowed by the possibility and actuality of constant death. The horrific killings of Blacks is sustained through police brutality against the historic context of slavery, White oppression, segregation, Black civil rights movements and an American dream forged through Black death as part of a visual regime. My article opens up with the question from a Black student posted on a research mailing list online, on the troubling phenomenon of consuming Black bodies in demise in repeat mode on the internet. The student's query bridges a number of issues including the role of the digital sphere as a virtual graveyard in shaping Black consciousness and communion, given the internet's 'body snatching' tendencies in which violence, death and bodies struggling to 'breathe' float infinitum. Why do we need the 'racialized' in 'racialized capitalism'?[1] In his recent article for Field Notes,[2] Charlie Post insists on the need to think racism and capitalism together but is keen to move the discussion 'beyond racial capitalism' perspectives[3] because of disagreements about the spatial and temporal origins of racism, and about the explanation those perspectives offer for the reproduction of racism in capitalist societies. While there is much to welcome in Post's carefully-crafted account, there are four areas of disagreement to which I want to draw attention. First, whatever substantive critiques one might wish to level at racialized capitalism perspectives, it is premature to speak of going 'beyond racial capitalism' or to claim that 'the notion of 'racial capitalism' is redundant [because] there is no 'non-racial' 'capitalism,' without a more thorough consideration of the political and theoretical work these perspectives perform in the present moment. Post certainly acknowledges that they emerged out of the reverberations of collective action against state racism, particularly the desire of a new generation of activists to make sense of racism's continuing power to inflict damage and death. However, there is much more that needs to be said on the matter. In particular, racialized capitalism perspectives help make transparent the constitutive role racism played in the formation and reproduction of capitalist modernity. This is no mean achievement, given that much of public discourse, along with liberal and critical thought, continues to minimize and underestimate its structuring power and significance.

Cross-posted from Spectre.

'For us who are determined to break the back of colonialism, our historic mission is to authorize every revolt, every desperate act, and every attack aborted or drowned in blood.' – Frantz Fanon, The Wretched of the Earth [1] On July 19, 2016, Adama Traore, a 24-year-old Black construction worker, was killed after an arrest by three police officers in Beaumont-sur-Oise, a northern banlieue, or suburban outskirt, of Paris. Adama was stopped for an identity check — a not uncommon measure by which police officers stop individuals and ask for their identification (often disproportionately targeting Black and Arab individuals). In this case, Adama was taken to a nearby police station and by the time he arrived, he was dead. The police originally stated that he had died of a heart attack, and then said he had prior health conditions which caused his death. In late May, the three police officers were cleared in their involvement for Adama’s death.

I’d just handed the baby over to my partner after the breakfast shift last Thursday morning when a friend messaged me. Activists had tweeted that an immigration enforcement raid on Kenmure Street in Pollokshields was being blocked by local people. My friend lives on the other side of town, but I live round the corner. ‘On way’, I replied. I pulled some trainers onto my bare feet, told my partner what was happening, and left the house.

The van was parked in front of another friend’s flat. 'IMMIGRATION ENFORCEMENT', with the targets of the raid inside. Ringed by police officers facing out, surrounded by protestors facing in. (I didn’t know until later that someone was lying under the van to stop it moving.) My friend was there at the front, face mask on, talking sharply to the police. His partner, nine months pregnant and with the home birth team on call, came out later with their two-year-old. Not that the home birth team would have been able to get through: police vehicles already blocked the street in both directions, up and down the block. I took a picture of the immigration enforcement van and the ring of police, and tweeted it. People on Twitter immediately noticed the black-and-white union jack with a ‘thin blue line’ down the middle that one of the officers was wearing.

In an age defined by hyper-visibility made possible by always-on digital media, brought to our fingertips by the smartphone, we are regularly fed images of (often extreme) racial violence. The circulation of the long eight minutes and forty-six seconds of George Floyd’s murder by Minneapolis police officer, Derek Chauvin, in May last year reinvigorated a movement across the Global North, against the disposability of Black lives. However, there is no simple way to untangle the dilemma that there is a seeming need to witness the death of a Black person to trigger a response. As LeRon Barton wrote, ‘watching Black men being beaten on video is the new lynching postcard.’

Despite the energy unleashed by the Black Lives Matter protests of 2020, it is not surprising that many antiracists remain sceptical about the lasting commitment of those momentarily inspired by the uprising. Will 2020’s #BLM moment be superseded by a return to scrolling through images of racial violence to which we seem increasingly immune? These questions animate my Identities article, ‘Looking as white: anti-racism apps, appearance and racialized embodiment’, which looks at mobile apps for reporting on and educating about racism. As mobile technology is such a part of our everyday experience, it can clearly be a powerful tool for pedagogy. This is the aim of one of these apps, the Australian-based Everyday Racism app. The app encourages ‘bystanders’ to learn about the experiences of people of colour and Aboriginal people who face racism in their daily lives. It uses gamification to deliver text and video messages to app users about these experiences in the aim of building empathy and encouraging what Australian racism researchers call ‘bystander antiracism’ (a strange appropriation of a concept used to describe those who stood by and did nothing during the Nazi deportation of the Jews).

The illusion of Britain as a post-racial society, or at least a multi-cultural society at ease with racial mixing and mixedness that the royal wedding of Prince Harry and Meghan Markle conjured up, has been wiped aside by the couple’s revelation of the racism they had faced within the royal family, including questioning about the potential skin colour of their first born. Britain may have around one in ten of couples in a mixed relationship, but clearly this does not signal antiracist progress. Meghan will have dealt with overt and covert racism all her life, but it must have been a steep learning curve for Harry. What will this mean for how he seeks to bring up his son and soon-to-be born daughter?

In my Identities article, ‘Partnered fathers bringing up their mixed-/multi-race children: an exploratory comparison of racial projects in Britain and New Zealand’, I took an in-depth look at how fathers of mixed-race children sought to equip them to deal with racism, and give their children a sense of identity and belonging. Drawing on racial formation theory, I explored the individual racial projects that they pursued for their children, interacting with historical, social and political nation state racial projects.

In this current moment where so many white individuals are contending with the implications of their racial privilege in the wake of the #BlackLivesMatter movement, it is important to understand the nuances of white identities. Much of the activism and effort over this past year has focused on urging white individuals to develop an awareness of the scope of racial inequality and white privilege. Less attention has been given to how white individuals might ethically deploy this racial understanding, especially regarding how white individuals might negotiate their participation within communities in which they are deemed racial outsiders.

My Identities article, ‘Ivory in an ebony tower: how white students at HBCUs negotiate their whiteness’, examines one such group of white individuals navigating their whiteness in a space where they are deemed racial outsiders: historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs).

The recent Black Lives Matters (BLM) protests offer a juncture for Britain to have a broad and sensible conversation on race and racism, similar to that headed by the Clinton administration in America 20 years ago. The recent re-appearance of the debate on terminology – the question of how to refer to racialised groups in Britain – may be the beginning of this. It is not a new question but is being posed by a new generation of Black Britons, who having been born in the UK should be unfamiliar with Hall’s sense of living ‘on the hinge between the colonial and post-colonial worlds’ (Hall & Schwarz 2017, 11).

In my Identities article, ‘The stigma of being Black in Britain’, I argued that despite more than 50 years since Britain adopted its first Race Relations Act (1965), colour remains a ‘visible feature of the urban landscape’ (Hall & Schwarz 2017, 184) in the UK. I described Brexit as an indication that, as Stuart Hall wrote many years ago, many of the ‘white underprivileged…believe that what they experienced was not because they were poor and exploited but ‘because the blacks are here' (Hall & Schwarz 2017, 185).

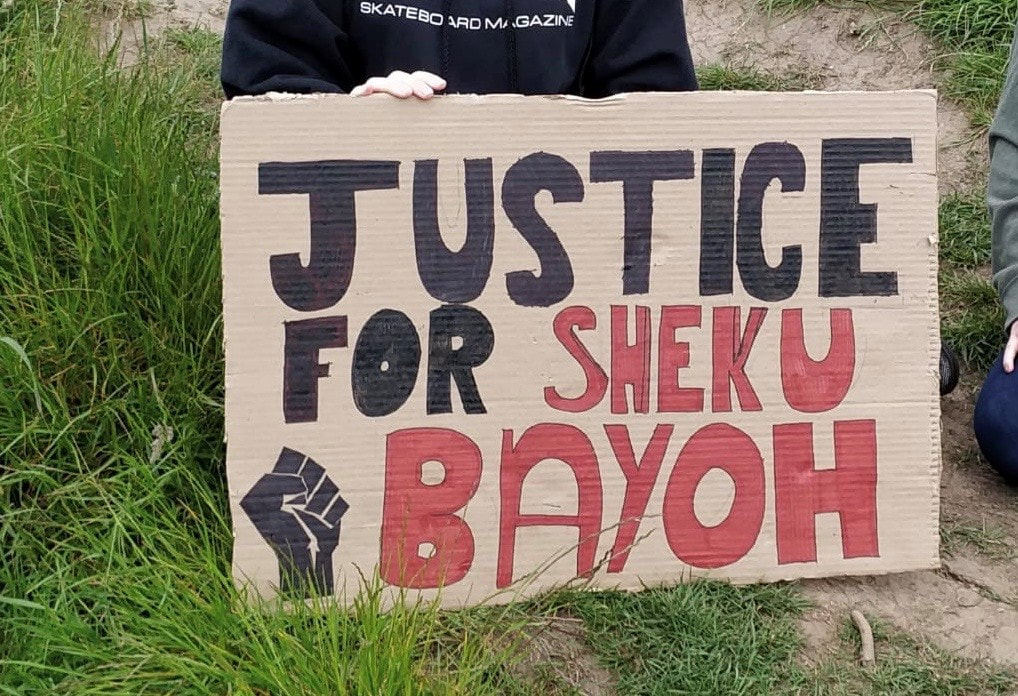

Sheku Bayoh died shortly after he was arrested by up to nine police officers in the early hours of 3 May 2015 on a quiet street in Kirkcaldy, a small town on the east coast of Scotland. Sheku’s mother had encouraged him to move to Scotland to be near his sister because she thought a young black man would be safer in Scotland than in London. CCTV footage has shown that Sheku was on the ground and restrained within less than a minute of police officers arriving, yet the postmortem revealed he had 32 injuries to his body. The Lord Advocate of Scotland announced in November 2019 that no police officer would be charged for Sheku’s death, four and a half years after Sheku died.

I wrote my Identities article, 'Containment, state racism and activism: the Sheku Bayoh justice campaign', not only to shed light on the circumstances of how Sheku died after he was arrested but to attempt to explain why deaths in police custody happen, why they are disproportionately of black people, and to develop an understanding of why the families who have lost loved ones find it so hard to get justice or even an adequate explanation from the police of why. I argue that the state has an interest in containing working class struggles and that state racism is used as part of the containment strategy that explains black deaths in police custody. I use a historical and theoretical analysis of how racism has been deployed by the state in immigration legislation where the black presence was problematised. The problematic black presence discourse has historically been a key feature of the policing of black communities – although this has evolved in several ways it nevertheless continues to produce a racial criminalisation of black people.

When writing public-facing policy-related reports, it is pro forma that the author(s) put forward a series of recommendations. Most of the time, writing recommendations is a data-/evidence-led process. What is more, some of the standard academic advice on writing recommendations includes things like ensuring that the recommendations speak directly to the aims and objectives of the project, acknowledging any limitations of the research and, where relevant, proposing further research. It also strikes me that writing recommendations can be an afterthought – a task left until the final full stop has been put on the conclusions.

Over the past seven years I have been involved in co-authoring reports on subjects ranging from the public impact of Irish Republican and Loyalist processions in Scotland, workplace racism, and more recently racism, institutional whiteness and racial inequality in higher education. Towards the end of this summer, I carried out a thematic analysis of the recommendations put forward in key government and non-governmental reports relating to racism and racial inequality in Britain on behalf of the Stuart Hall Foundation. Eight recurring themes emerged from the analysis of the 589 recommendations advanced in thirteen reports, ranging from the 1981 Scarman Report into the causes of the Brixton riots, through to David Lammy MP’s 2017 report ‘into the treatment of, and outcomes for Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic individuals in the criminal justice system’. Truth be told, this research was a depressing and blunt reminder that the recommendations put forward in reports are rarely ever acted upon, even though the report findings are typically greeted with performative enactments of shock, shame and concern. Indeed, the failure to act evidences a longstanding lack of political commitment to unsettling the coordinates of racial hegemony and disturbing orthodox ways of doing things. So much so, I am reminded of the words of the late Black novelist, playwright, essayist, poet and activist, James Baldwin, who once asked, ‘How much time do you want for your "progress?"’.

Henri Lefebvre and C.L.R. James were quintessential twentieth-century intellectuals. They were born within six months of each other in 1901. Both lived to within sight of the century’s end: James died in 1989 and Lefebvre in 1991. And, as I argue in my Identities article, 'Passing through difference: C.L.R. James and Henry Lefebvre', their grappling with the times in which they lived led them to articulate a comparable politics.

What kind of politics? One which valued human flourishing more than formal equality. One which considered creative freedom more significant than technological progress. And one which found hope in the way in which ordinary people fought against constraint in their day-to-day lives. Handsworth and the production of knowledge: Blackness, racism and anti-imperialism in 1970s Britain27/11/2019

The African Caribbean Self-Help Organisation (ACSHO), based at Heathfield Road in Handsworth, Birmingham, established itself as a central hub for Pan-African centred learning and intellectual debate in the early 1970s. ACSHO members were part of a UK-wide co-ordinating committee that sent a delegation of activists to the 6th Pan African Congress (6PAC) in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania in 1974. My Identities article, ‘Each one teach one’ visualising Black intellectual life in Handsworth beyond the epistemology of ‘white sociology’, shows how the conference statement by the UK delegation at the 6PAC meeting was critical of the inherent racism of their social condition in England’s metropolitan cities as well as of the racist ways they were being studied by white social scientists at the time. Through their own Pan-African centred and anti-colonial critique, the delegation used ‘scientific socialism’ to situate their political struggle within a global context of anti-imperialist resistance movements.

Inside this hive of Black intellectual activism emanating from Birmingham, the archival work of Vanley Burke is particularly noteworthy. Born in St Thomas, Jamaica in 1951, Burke recalls receiving a gift of a camera sent by his mother from England for his 10th Birthday. He became fascinated by the ‘magic of photography’ and was compelled by both the science and artistry of this medium (Sealy 1993). Since the early 1970s, Burke has documented the lives of Caribbean communities in Birmingham with an intimacy and sensitivity towards the people he shares the city with.

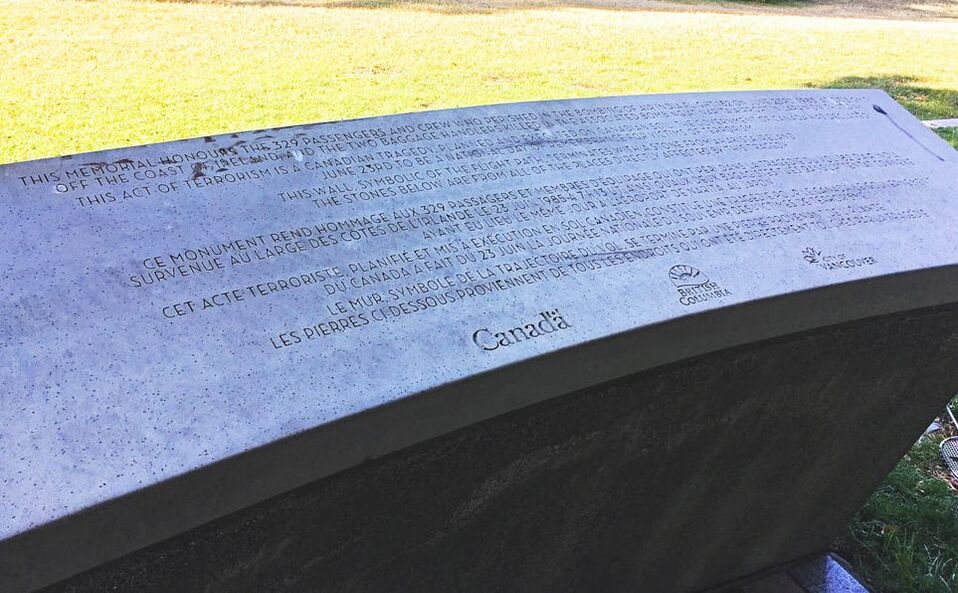

In June 1985, 331 people were killed in the bombings of two Air India flights, which investigators attributed to militant Sikh nationalist groups operating in Canada. Although the bombings are now regarded as the deadliest incident of terrorism in Canadian history, they continue to hold a complex, often contradictory place in Canada’s imaginary.

Much of the existing scholarship has attributed this complexity to systemic racism that limits how the bombings have been regarded and remembered as a ‘Canadian tragedy’ (Dean 2012, Failler 2009, Seshia 2012), even as the Canadian government devoted considerable resources to investigating and prosecuting the attacks. In 2006, the Government of Canada even commissioned a public inquiry to determine how state institutions failed to prevent and effectively prosecute the bombings. Given that the inquiry received evidence that systemic racism shaped state responses to the bomb plot, it offers a unique vantage point to examine how state institutions reckon with their implication in racial violence. 25 years after apartheid: are British-born South Africans signing up to the ‘rainbow nation’?2/10/2019

2019 marks 25 years since Nelson Mandela was elected as the first black president of South Africa. Finally, apartheid, the system of racial segregation institutionalised by the Afrikaans-led Nationalist Party in 1948, was a chapter closed. Since that time, South Africans of all backgrounds have been debating the extent to which the post-apartheid vision of ‘a rainbow nation’ -- a multicultural unity of people of many different nations -- is being realised.

This question is not only of interest and importance within South Africa. Against a context of rising populism and white nationalism across the Global North, are white people in South Africa really rejecting the privileges of white supremacism which they have enjoyed for so long? My Identities article, 'Reimagining racism: understanding the whiteness and nationhood strategies of British-born South Africans', examines this question by looking at one group of South African Whites: those who were born in Britain and migrated to South Africa. Many did so in the 1960s, 70s and 80s, through a ‘Ten Pound Pom’ scheme which offered them cheap passage, good jobs and comfortable accommodation on arrival. Whereas, at home in Britain, there was rising rejection of the apartheid system in South Africa, this group chose to up sticks and move to a deeply segregated society. How do they explain this, to others and themselves? And how do they now talk about the situation in South Africa today?

How much should biology matter to our identities? When it comes to race and ethnicity, many people believe there are biological differences between groups. Actually, despite what many think, geneticists have proven that all humans are more than 99% genetically similar regardless of race. Even though these discoveries made in 2000 were widely reported in the news and in academic settings, most people (including academics!) continue to use assumptions that biology is relevant to determining who we are and to what groups we belong.

In today’s society, many people believe they are 'colourblind' and that we are 'post-race' — in other words, they think race shouldn’t matter anymore, that racism is a thing of the past, and that everyone has an equal chance at succeeding in society. Another part of 'colourblind' thinking is that we have changed the way we talk about race. Today it is far more common to use code words such as 'illegals', 'inner-city', or even to talk about culture as a stand-in for talking about racial groups.

'First, I'll need tenure. And a big research grant. Also access to a lab and five graduate students — at least three of them Chinese.'

- Professor Ogden Wernstrom, Physicist Those are Professor Ogden Wernstrom’s demands when asked to save the Earth from a giant garbage ball approaching through space in the Futurama episode, A Big Piece of Garbage. Portrayed as an obvious antagonist, Wernstrom seems greedy and exclusively concerned with his own career advancement. He also seemingly regards grad students as just another commodity to further his own goals, with Chinese students as particularly valuable or useful assets. This specific view on Chinese researchers as not much more than pricey pieces of high-tech equipment was provided by a cartoon villain 20 years ago, but it arguably still falls into the questionable category of 'it’s funny because it’s true': it indeed resonates with prejudices that extend beyond the Futurama universe and into real-world academic discourse. |

|

Explore Identities at tandfonline.com/GIDE |

|

The views and opinions expressed on The Identities Blog are solely those of the original blog post authors, and not of the journal, Taylor & Francis Group or the University of Glasgow.