|

|

|

Blog post by Siow-Kian Tan, Xiamen University, Malaysia

Food has the incredible ability to bring people together, yet it can also stir up debates over its origins. Dishes like Laksa, Nasi Lemak, Bak Kut Teh (BKT), Hainanese Chicken Rice and other local favourites have been passionately claimed as national dishes by both Malaysians and Singaporeans. This culinary dispute isn’t new. Back to 2009, Malaysia’s then-tourism minister, Ng Yen Yen, sparked controversy and patriotic fervour in both neighbouring countries by suggesting that Malaysian cuisine had been ‘hijacked’ by others. Each side adamantly defends dishes like nasi lemak, BKT and chilli crab as authentic and original, and criticizing the other of appropriating culinary heritage. However, are such disputes meaningful and can a dish genuinely belong to a single nation? In 2023, Channel News Asia’s ‘On The Red Dot’ programme delved into these questions, interviewing chefs, hawkers and heritage experts to uncover the origins and stories behind iconic dishes like chili crab, BKT, nasi lemak and cendol. Hosted by Ming Tan, a chef and culinary consultant, this captivating series explores how dishes evolve and travel across borders.

0 Comments

Blog post by Les Back, University of Glasgow, UK

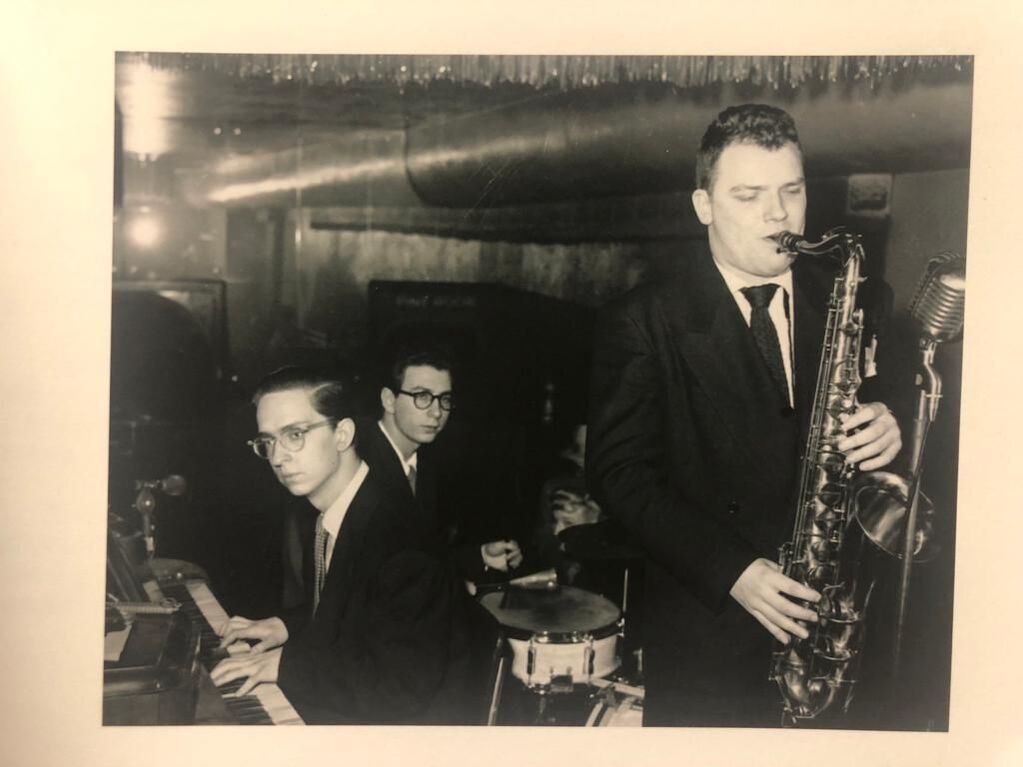

Howard S Becker’s life provides the archetype for the argument developed in my published Identities article, ‘What sociologists learn from music: identity, music-making, and the sociological imagination’. Its completion coincided with the sad news of his death on 16th August 2023 at his home in San Francisco aged 95. In a way, my Identities article is an homage to one of the greatest sociological minds of our time, and a pretty decent piano player too. The study, based on interviews from 29 contemporary sociologists, found that musical life offers sociologists an interpretive device for understanding society or practical form of insight. This is not only confined to the artful sociology at the more humanities end of the disciplinary spectrum, but can be found even amongst scholars who see sociology as a science.

Blog post by Annavittoria Sarli, University of Birmingham, UK

Policy and media discourses in Italy refer to migration-related issues mostly in the language of emergencies, deviancy or alleged cultural threats. The everyday presence of ethnic minorities as a permanent constituent of society is rarely acknowledged. Such public discourse perpetuates a kind of socio-cultural immaturity, making it difficult for the population to accept growing diversity. ‘Italianness’, moreover, tends to be conceived as monoracial and monocultural. This idea of national identity drives an imagined net division between a monolithic national ‘us’ and ‘the others’ foreigners, who comprise both first generation migrants and their Italy-born descendants. It is an imaginary enshrined in the Italian law on citizenship, introduced in 1992 and never updated since then. Mainly based on jus sanguinis, it poses obstacles for migrant immediate decedents (MIDs) to become citizens of the country where they spent most of their lives.

Blog post by Hamdullah Baycar, University of Exeter, UK

‘It kind of makes me feel like Batman or Superman. You can say the things you want to say with your own voice and your own style’, said Malcolm Bidali, a Kenyan security guard employed in Qatar, regarding his activism about labour conditions on social media. His activism led to his detention in 2021. The incident gained significant public attention, and 240 Qatar Foundation students, alums, faculty and staff signed a petition asking for his release.

Two days after the petition, even Qatar's state-owned media, Al Jazeera, was involved in the debate and ran with the headline, ‘Concerns over Qatar's arrest of a Kenyan security guard’. Thus, the digital sphere, which initially caused his detention, ultimately became the tool that freed him. Although Bidali's case cannot be considered representative of the entire Gulf region and is not directly related to the UAE, it does demonstrate the power of social media and the digital sphere, even in supposedly autocratic states.

What does a Thai person look like? How do expectations about citizenship create an ethicized cultural phenotype? In our Identities article, ‘Turbaned northern Thai-ness: selective transnationalism, situational ethnicity and local cultural intimacy among Chiang Mai Punjabis’, we explore family histories, selective transnationalism and regional Lanna identities among Thai citizens with Punjabi heritage and selective cultural identity. This article argues that Punjabi Thais maintain their networks and cultural connections with a historic ancestral homeland, but they also cultivate forms of local cultural intimacy in ways which leapfrog the linguistic and cultural hegemony of Thai national identity. In other words, despite their non-Thai appearance, these Punjabi Thais have deeply local cultural knowledge, speak Northern Thai language fluently and have Northern Thai cultural sensibilities.

Young people in ethnically divided post-conflict societies are often happy to date across ethnic lines, notwithstanding its prevailing discouragement. My recently published Identities article, 'Kiss don't tell: attitudes towards inter-ethnic dating and contact with the Other in Bosnia-Herzegovina', examines this in Bosnia-Herzegovina, which it takes as a typical case of an ethnically divided post-conflict society: young people struggle to meet other ethnic groups due to the high levels of segregation in society. Such contact is also discouraged in the home, in schools, in religious institutions and in the media. I use focus groups conducted on Facebook and follow-up interviews to speak to young people across the country who date across ethnic lines despite these obstacles.

After living in Miami, Florida, for several years, Mother Frances Butler returned to her home in Nassau, Bahamas and founded the Mother’s Club, which provided social welfare support to the Bahamian Black community. Along with similar groups, the organization offered a variety of social services where they fundraised as a part of hurricane recovery, aided the war effort and offered health and other social services for women and children. In 1937, Mother Butler changed the title of her organization to The Young Women’s Christian Association.

The building that formerly housed the Mother’s Club sits at the corner of Goal and East Street in the heart of Nassau. The building is in the Grants Town community and was originally established by the Bahamian government to house freed people and Liberated Africans in the early 1820s. This area is one of the communities located in what is known as the ‘Over the Hill’ neighbourhoods in Nassau. These neighbourhoods became a rich site of Black life during the 19th and 20th centuries, as Black people in the Bahamas encountered poverty and racial oppression. Mother Butler also founded other Black-led organizations, including the Young Men’s Christian Association and the Silver Bells. Today, the world’s knowledge of Sweden is limited, and its image is often too unclear and out of date. So we need to unite around a clearer, unified image that better reflects contemporary Sweden – an image that is also distinct and relevant to the people we want to reach.

- Swedish Institute, 2009

Like handbags and toothpaste, countries are being branded. National identities and cultures are used to brand countries. For example, Malaysia is branded as ‘Malaysia, Truly Asia’, pointing to its multiculturalism. But identities are never static, and communities are diverse. So, which identities and whose cultures in the country are promoted, and which excluded?

The Swedish authorities are branding their country too, but they want the brand to be honest and inclusive, not fabricated and selective. Did they succeed? In our Identities article, ‘Representing Sweden: packaging Swedish identity through curators of Sweden’, we examine a recently concluded nation branding project, Curators of Sweden (CoS). The project used Twitter as a platform and each week a ‘Swedish’ person was chosen as a curator to tweet whatever they liked through the @Sweden account. The curators were chosen because they represented ‘values, skills, and ideas’ which, according to the campaign, ‘all combined, makes up Sweden’. CoS started on 10th December 2011, the Nobel Prize day, and ended in September 2018. A total of 356 curators tweeted more than 200,000 tweets.

Populist parties and leaders have become important actors across the globe. The 2022 presidential elections in France, and parliamentary elections in Sweden, as well as Turkey’s 2023 presidential elections not only revived academic research on populism and stirred scholarly debate about how to conceptualize it, but also compelled electors and political actors to reflect on the political developments taking place on the populist right front.

In our Identities article, ‘The veil as an object of right-wing populist politics: A comparative perspective of Turkey, Sweden, and France’, we selected three countries which have extremely different religious, secular, and cultural contexts. We then analyzed the political statements by the radical right-wing parties in each of the chosen countries: the Justice and Development Party (Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi, AKP) in Turkey, the National Rally (Rassamblement National, NR) in France and the Sweden Democrats (Sverigedemokraterna, SDs) in Sweden.

UNESCO’s Atlas of Endangered Languages recognises over 2,500 endangered languages worldwide. Languages represent not just a form of communication, but also the cultural knowledge of that language. However, in his book Language Death, David Crystal estimates that the world is in danger of losing nearly half of all accumulated knowledge at the current rate of language loss. With language intrinsically tied to culture, many communities that experience a decline in the use of their native language perceive it as a sign that their culture is dying. The result is often that older generations look for ways to maintain, transmit and revitalise use of their language through younger generations.

The internet is intrinsically connected to issues of language and cultural identity. As language is the primary means for spreading cultural information, internet resources in minority languages can empower speakers of these languages by enabling them to display their own way of life and voice their concerns and issues in their mother tongue. In this way, they may revitalise their languages, reinforce cultural symbols and strengthen cultural identities.

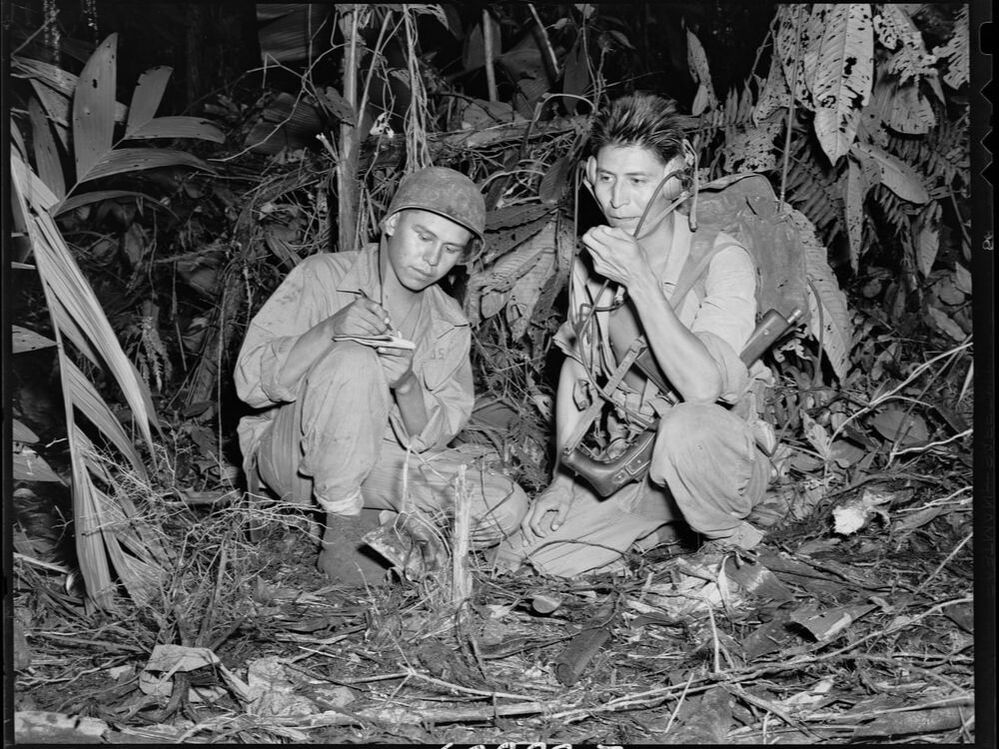

The global Indigenous Rights movement emerged late in the twentieth century, with scholars tracing its origin to postwar international conventions and human rights activism. In my Identities article, ‘World War II and the development of global indigenous identities’, and in a forthcoming book (War at the Margins, University of Hawai’i Press, 2022), I examine how the war created conditions favouring the emergence of Indigenous identity as a form of global political action.

The Second World War mobilised human and natural resources on a massive scale; its aftermath dissolved empires and rearranged the international order. Indigenous men and women — those in small-scale, often tribal, societies at the fringes of national or imperial control — were drawn in as soldiers, scouts, laborers and victims. New Zealand’s Māori Battalion, Navajo codetalkers in the US Marines, Naga guides for the British Army, New Guinean carriers for Allies and Japanese — these and other Indigenous actors shaped the progress, and sometimes the outcome, of campaigns. Even where front lines did not cross Indigenous homelands, civilians suffered violence, displacement, military occupation, economic and social disruption and forced labour. War created a fluid context for change, highlighting the ambiguous legal position of Indigenous people and altering government and public views of them.

Due to the accessibility of the internet and the ability of online spaces to bring people together, platforms like social media sites and web forums have allowed globally dispersed communities to engage in conversations about identity and belonging. For my Identities article, ‘Connectivity, contestation and cultural production: an analysis of Dominican online identity formation’, I collected and analysed text data from a web forum that I call ‘DRLive’ to show the kinds of identity discourses that happen online. This site caters to all things Dominican Republic, with free and open forum pages where Dominicans and non-Dominicans participate in discussions covering numerous topics. Adding to work on diaspora, migration, and cultural production among Dominicans, I propose forums and other virtual spaces as additional sites where diasporic and non-diasporic Dominicans come together to talk about and challenge evolving interpretations of identity, history and cultural memory.

Cultural memory, which is defined as a collection of commonly shared historical moments and experiences, is passed on and shared over time by members of a nation. In the case of this forum, for example, I find that ‘the contrived historical narratives propagated in the Dominican Republic throughout the 19th and 20th centuries continue to inform how Dominicans in the country and in the diaspora interpret and construct Dominicanidad.’ Work on virtual spaces often seeks to address how migration might affect the maintenance of cultural memory, especially as second- and third-generation immigrant communities emerge far from their homeland.

Our identities reflect our relationships with places and spaces. The changing contexts of these relationships also impact, shift and mould our identities. In our Identities article, ‘Hybrid identities: juxtaposing multiple identities against the ‘authentic’ Moken,’ we explore Moken[i] communities living in coastal areas of Thailand, and the Indian Ocean tsunami of 2004. We also spotlight ascriptions of Moken identities as vulnerable, overwhelmingly linked to the sea and with limited opportunities for agency over their livelihoods.

In challenging these ascriptions through our ethnographic research, we found myriad examples of agency with various beliefs, settlement patterns and usage of the sea. The communities we spoke to explained shifting identities, across and between physical spaces of settlement, but also among traditional practices and aspirations for younger generations. That our identities shift and flux is a position made overwhelmingly clear during the past year when the spread of COVID-19 has significantly changed our capacity to relate to different places and spaces. Our experiences of this past year have been contingent on national contexts and structural inequalities, as well as long-held assumptions about certain cultural identities.

As India hosted the World Environment Day celebrations in 2018, the prime minister, Narendra Modi, addressed the nation through his radio programme:

This is a very important achievement for India and it is also an acknowledgement as well as recognition of India's growing leadership in the direction of tackling climate change. This time, the theme is ‘Beat Plastic Pollution’. I appeal to all of you that while trying to understand the importance of this theme, we should all ensure that we do not use low-grade polythene and low-grade plastics and try to curb the negative impact of plastic pollution on our environment….Our culture, our traditions have never taught us to be at loggerheads with nature. In his speech, India was projected as a leader in addressing climate change and a putative Indian culture was extolled as being effortlessly ecologically friendly. However, Modi’s claim of an environmentally-friendly Indian tradition is not supported by empirical evidence. For example, notions of civilisation in pre-colonial India– rather than preservation – of forests. Similarly, the intensification of traditional agriculture had detrimental ecological consequences even prior to the commercialisation of agriculture under colonial rule. Nevertheless, this claim of an ecologically sensitive Indian past is widely encountered – and promoted – in India and abroad.

In a BBC interview in 2019, Jonathan Powell, Tony Blair’s former Chief of Staff, declared, to the bewilderment of journalist Emily Maitlis, that much of the turmoil over Brexit’s impact on Northern Ireland was driven by questions of identity – particularly national identity. Such concerns have always been central within party-political wrangling in the region. However, the UK’s departure from the EU has placed Northern Ireland’s ‘national question’ in focus globally. Britain’s divorce from its European membership includes the so-called ‘protocol’, which maintains significant alignment between Northern Ireland and the rest of the EU to avoid a physical border in Ireland itself. However, part of this ‘solution’ is instead the implementation of a trade border in the Irish Sea for goods travelling between Great Britain and Northern Ireland.

This seeming economic detachment from the rest of the UK has angered those who view their Britishness as central, or at very least important, to their own identity. However, questions around national identity in the region are much more than a simple dichotomy of Britishness versus Irishness. Identification by individuals as Irish, British, Northern Irish, ‘other’, or a hybrid of all of these reflects more complicated realities. For some individuals, other identity matters, such as those relating to gender or sexuality, might take primacy in their own sense of self or community. Regardless, debates around Brexit and the protocol’s implementation have placed real focus on Northern Ireland’s future. In some quarters, debates on Irish unification are building momentum and generating discussion on how these complex cultural affiliation(s) sit within the wider constitutional question. Disentangling culture, religion and economy in the native communities of the Shenzhen megalopolis7/7/2021

The rise of China is mostly perceived as an economic phenomenon. Yet, there is also the cultural dimension: What are the implications of Chinese leaders proclaiming that Chinese cultural traditions must be endorsed, as they essentially define what it means to be Chinese? The revival of popular religion in China, such as ancestral worship, which was suppressed over decades, but is now even applauded by President Xi Jinping as an expression of cherished core values of the Chinese, family and filial piety.

However, many phenomena related to religious practices in China defy conceptions of ‘religion’ developed in the light of Western historical patterns. Rituals are central in these phenomena, which can also be conceived as local customs and community traditions that express social norms and conceptions of social order without implicating ‘religion’. This ambiguity or even dissociation of ritual and religion is characteristic for East Asian societies and can be also observed in Japan, where ritual practices flourish, yet the majority of Japanese claim that they are ‘not religious’. Our Identities article, ‘Interaction ritual chains and religious economy: explorations on ritual in Shenzhen’, looks at these phenomena in the Shenzhen metropolis.

In memory of co-author Monique Nuijten. Thank you for all your inspiration and the nice partnership working on this article together.

‘A Breaker is peaceful and calm. At the moment of dancing he expresses all his feelings, he expresses his anger, his love, his sadness, everything. While dancing he develops. Breaking turns them into better people.’ ‘The moment you start to dance and become a b-boy or b-girl everything in you changes, it’s like an armor you put on and you will never take off.’ ‘This is what I love the most, it is what makes me, it is why I keep on fighting, the reason why I am still standing, it is the reason why I can keep on following my dream.’ ‘It is my life, without it [dance] I can’t live, it is like the air.’ In our Identities article, ‘When breaking you make your soul dance’ Utopian aspirations and subjective transformation in breakdance’, we dive into the world of breaking by following the Naturalz crew in Ecuador. The quotes above from various crew members illustrate the importance and meaning of breakdance for them. Breaking is commonly analysed as a subculture of resistance. We analyse two – often neglected – dimensions of this resistance: the significance of utopian aspirations and the role of the body in subjective transformation. The breakers shape a new lifestyle for themselves through breakdance. A lifestyle they fight to preserve every day.

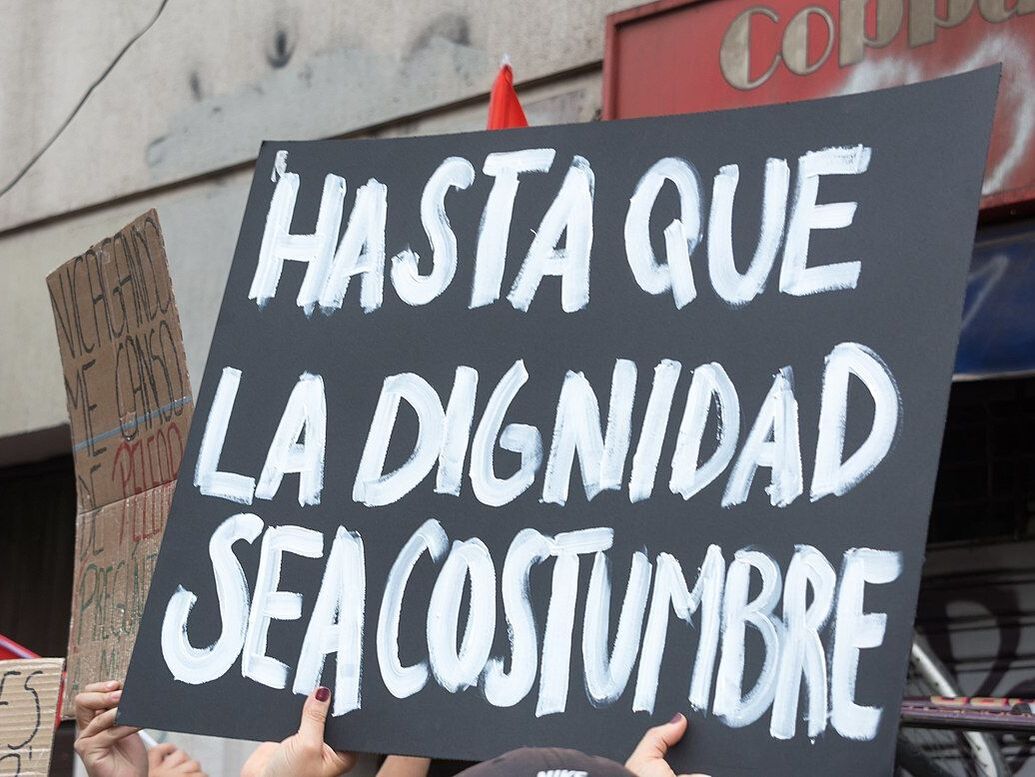

While writing our Identities article, ‘Disjunctive belongings and the utopia of intimacy: violence, love and friendship among poor urban youth in neoliberal Chile’, we had already started to witness a series of protests that recently culminated in the so-called Chilean ‘social outburst’ in October 2019 and the current process building a constituent assembly. Issues of quality of education, environmental concerns, shortcomings in the social security system, as well as long-standing efforts for the cultural and political recognition of indigenous groups gained increasing support over time. Yet, the many protests still appeared geographically scattered, and while people in the urban margins indeed felt uneasy with their life prospects, it was still uncommon to hear people articulate a more thorough critique of the neoliberal model that has prevailed in Chile for the past forty years.

In Los Acantos, the residents we met in 2012–2013 were conscious of these issues. Many of the young residents we met saw no way out in a world bounded off by invisible borders of social (in)difference and stigma. People were, in other words, aware of their almost impossible odds of socio-economic mobility and underneath the surface of monotonous low-income houses, the attentive ethnographer could feel the discontent.

Du Bois’ work provides invaluable insights into the nature of reflexivity and self for the racialised 'other', which traditional, classic sociology has often overlooked. Whilst efforts to decolonise sociology continue, such as by including theorists such as Du Bois, there still has not been a sustained effort to dismantle and reconfigure an overwhelmingly white sociological canon still prevalent in European sociology (Meer 2019).

In his seminal work, The Souls of Black Folk (1903 [2007]), Du Bois centres discussion of belonging, identity and self-awareness for racialised minorities through concepts of the ‘Veil’ and ‘double consciousness’. Du Bois’ analogy of the Veil is that of a racial barrier which is made of material in the divided experiences and inequality between the white majority and African-American minorities in the USA. For Du Bois, the Veil’s semi-transparency lends itself to the duality experienced by the racialised ‘other’: a double consciousness or a ‘two-ness’ which incorporates a ‘sense of always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others’ (p.8). In my Identities article, 'Examining BSA Muslim women’s everyday experiences of veiling through concepts of ‘the veil’ and ‘double consciousness’, the focus is on a reflective aspect of living behind the V/veil and the effects of double consciousness on gendered and racialised bodies. Here the capitalisation of the Veil is used to denote Du Bois’ descriptions of a divided world, whilst the non-capitalised use of veil (along with discussion on veiling, veiled) refers to the wearing of the hijab or niqab, as well as ways women discuss veiling practices.

In the 1930s, the retired British governess Mary O’Neill lived in Florence in the company of her female co-nationals. A close-knit diaspora of English aristocratic intellectuals and bohemians, they sought to spread English cultural traditions to the Italian masses. They tried to help ordinary Italians enjoy Shakespeare and Renaissance art, not only to dream about glamorous cars and other pleasures of the Jazz Age. Mary O’Neill and her friends greatly contributed to the upbringing and the artistic rise of the young Franco Zeffirelli. But did they manage to gain prestige within their Italian community? Known for their poignant wit, those expat women, whom the locals sarcastically called ‘Scorpions’, were, in fact, totally alienated from a wider Florentine community.

Depicted in Zeffirelli’s Tea with Mussolini, this story of cultural resilience finds a lot of resonance with diasporic reality today. In the large volume of studies on diaspora, an issue of concern is that many expats who speak culturally and civically on behalf of their homeland find zero reciprocity within their local community (Nye 2004; Watanabe and McConnell 2008). Why do highly intellectual expats, who seek to morally enrich their host society, often fail to be accepted by their local communities? This question is explored in-depth in our Identities article, ‘Reflections on diaspora and soft power: community building among female US expats in Southern Europe’, which looks at life experiences of highly educated US-national expat women in Italy and Greece from the 1990s to 2015. They all hold degrees from leading US universities. Many of them are married to local men. And all of them seek to spiritually invigorate their local communities by showing them how to take care of the public space, such as to clean streets from litter and set up shelters for stray dogs and cats. They see these as typical ‘North American civic values’ that they are teaching to their ‘unenlightened’ neighbours.

Difference is something that exists in the bodies and culture of ‘others’

Sara Ahmed, 2007 In the wake of the recent intensification of activism and debate on why and how Black Lives Matter it is important to keep interrogating the multifaceted ways in which racism is pervasive within institutional practices – often in not immediately visible ways. In the UK, the current hostile environment (Grierson 2018) is designed to create forms of social disadvantage for migrants, especially those in situations of vulnerability, feeding into an ever expanding and invisibly coercive system of oppression. Our London-based research explored the kind of support that asylum seeking and migrant women receive by charities, especially around mental health. Compared to statutory services, charities are able to better understand and address the complex intersection of social, political, economic and emotional factors at stake in mental health, as opposed to psychiatric diagnoses which often tend to decontextualise people’s experiences of distress. Third Sector Organisations (TSOs) are well suited to respond to complex needs of asylum seeking and refugee women because the support they provide relies on empathetic understanding for different aspects of these women’s lives – ranging from acknowledging culturally embedded notions and experiences of mental health to being responsive to the structural position they are placed in by the state and society. Both material and emotional support are particularly important for newly arrived migrants, who have weaker social ties in the host country, are often less able to navigate support systems due to language barriers and because they are unfamiliar with or denied access to statutory services.

In our Identities article, 'Digital institutions: the case of ethnic websites in the Netherlands', we conceptualised websites as digital institutions. Since the concept of institutions appears to be fuzzy, comprising formal and informal as well as micro and macro organisations, we argued that they, although socially embedded and culturally loaded, conceptually are insufficient to highlight their specificity. In order to specify the institution, we employ the concept of script, defined as recurrent activities and patterns of interaction. Empirically, we apply this concept to detail ethnic websites in the Dutch Hindustani community and to highlight what needs they fulfil for its visitors and in the Hindustani community. We argued that these ethnic websites fulfil a wide range of needs — notably, as a means of communication, a platform on which community members can address ethnic issues, a device through which to build networks, and a place from which to download material — thus fostering the identity of the ethnic group. Since evidence based on one community may be a matter of happenstance, we substantiate our argument with a comparison of ethnic websites from the younger generation of white Dutch, Hindustanis and Moroccans in the Netherlands.

When I was asked to write a blog to accompany my Identities article, 'The most cosmopolitan European city: situating narratives and practices of diversity in Marseille', I was asked to provide a suitable image. This faced me with a dilemma that cuts to the heart of my argument: how to choose a picture that symbolises cosmopolitanism in Marseille without falling into stereotypical representations of what and where cosmopolitanism is, and who represents it?

Searching the internet for images of 'cosmopolitan Marseille' in English and in French ('Marseille cosmopolite') brought up quite different results. In the English language search, the majority of photographs showed shots of Marseille intended for international tourists: terrace cafés, well-known landmarks and generic promotional images from restaurant chains, bars and rental apartments. There was just one picture of a busy multi-ethnic market street. In the French search, similar touristy images also came up, alongside images that felt both more everyday and more ‘local’: interiors from different shops displaying open bags of spices for sale and a photograph from the municipal website of local politicians receiving international delegations from Marrakesh and Dakar, accompanied by a title describing Marseille as coloré et cosmopolite ('colourful and cosmopolitan'). There were, in addition, several references to specific impoverished neighbourhoods in the city-centre that are often taken as the embodiment of Marseille’s ‘cosmopolitanism’ while at the same time are the target of local and national urban renewal programmes that seek to attract a different - less ethnically-marked - population into the city centre for many decades now.

Indonesian women victims of domestic violence commonly experience a sense of shame, however unreasonable that might seem to those outside the community. However, it is understandable for two reasons.

Firstly, most Indonesians consider marriage a sacred institution, the harmony of which must be maintained to support not just the marriage itself but broader social harmony. Secondly, to Indonesians the wife is seen as responsible for maintaining family harmony due to the values of nurturing and caring traditionally assigned to the female gender. Hence, a failure to maintain marital or familial harmony is blamed on the wife who, should she decide to divorce, may be described as an ‘unfaithful wife’, ‘undutiful housewife’ and an ‘unloving mother’, with little or no basis for such accusations. Even when domestic violence has occurred and the marriage cannot reasonably continue as there is threat of continued physical and emotional violence and other abuse of the women and their children, the women still feel shame. Having internalised societal values, women feel that they have failed to meet society’s and their own expectations.

Patronato is a well-known commercial neighbourhood in Santiago, Chile with a tradition of migrants’ settlement and entrepreneurship that dates back to the nineteenth century. Today, the area is branded as a textile and vibrant ‘multicultural commercial neighbourhood’, as read in several street signs. Traders and workers’ ancestries include Chilean, Korean, Chinese, Indian, Peruvian, Palestinian, Syrian, Haitian, Colombia and Venezuelan, among many others. Yet, despite its growing diversity, Patronato is often described (in the media, films and popular narratives) as a Palestinian-Korean neighbourhood.

In our Identities article, ‘Contested and interdependent appropriation of space in a multicultural commercial neighbourhood of Santiago, Chile’, we analyse memories, images and uses of space by entrepreneurs of Korean and Palestinian ancestry, as well as their competing and reciprocal appropriation of space. Through processes of social production and construction of space (Low 2017), we examine their experiences of making, inhabiting and appropriating space, in relation to the transformations of the political economy. |

|

Explore Identities at tandfonline.com/GIDE |

|

The views and opinions expressed on The Identities Blog are solely those of the original blog post authors, and not of the journal, Taylor & Francis Group or the University of Glasgow.