|

|

|

Blog post by Les Back, University of Glasgow, UK

Howard S Becker’s life provides the archetype for the argument developed in my published Identities article, ‘What sociologists learn from music: identity, music-making, and the sociological imagination’. Its completion coincided with the sad news of his death on 16th August 2023 at his home in San Francisco aged 95. In a way, my Identities article is an homage to one of the greatest sociological minds of our time, and a pretty decent piano player too. The study, based on interviews from 29 contemporary sociologists, found that musical life offers sociologists an interpretive device for understanding society or practical form of insight. This is not only confined to the artful sociology at the more humanities end of the disciplinary spectrum, but can be found even amongst scholars who see sociology as a science.

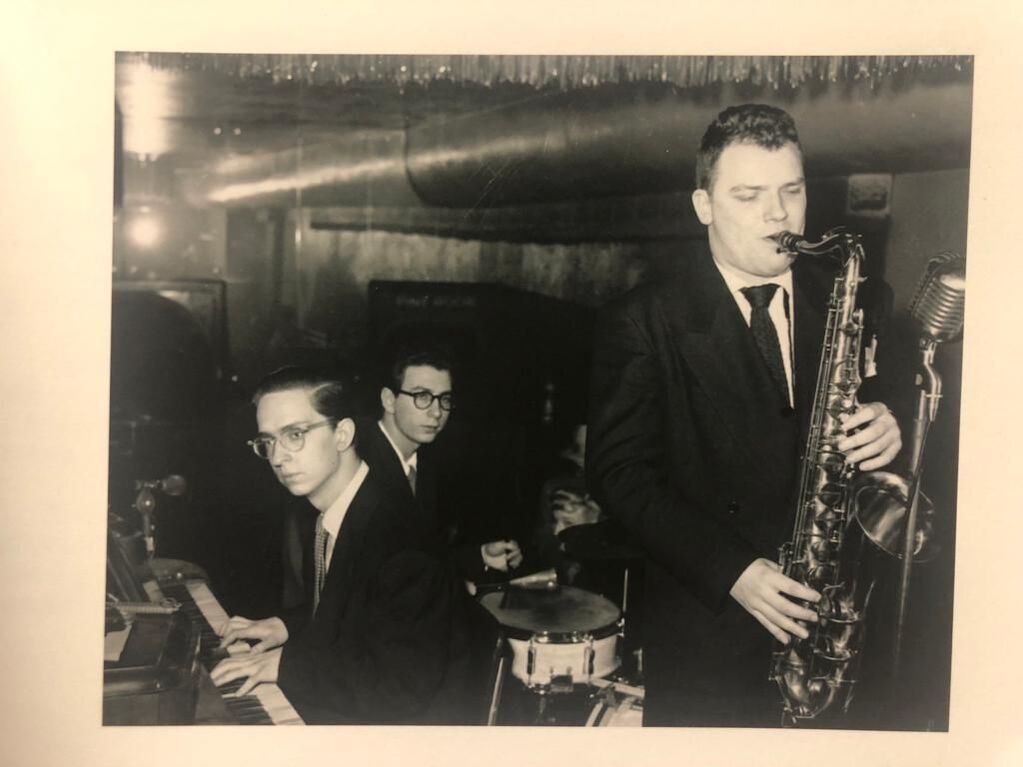

Howie, as he was known to his friends, was a maverick, and a brilliantly irreverent thinker. His classic study Outsiders (1963) is built out of his experience of playing jazz and popular tunes in Chicago strip joints and taverns in the 1940s and 1950s. He was just 15 years old when he started playing professionally in jazz trios during World War II, when most musicians were in the army. He explained: ‘There was a shortage of musicians… so everybody winked at the fact that there were these kids like me working in there.’ He became a ‘tune hound’ fascinated with the chord structures of the jazz repertoire, but he also studied with the legendary Chicago piano player Lennie Tristano. As a teenager he was playing in bars 7 hours a night until 4am, making $80 dollars a week and a living wage of $4,000 dollars a year. This was as much as a junior academic was earning in the 1950s. Becker received his undergraduate degree in sociology at the University of Chicago in 1946 and continued his studies there, gaining an M.A. before writing a doctoral dissertation on Chicago school teachers. He finished his PhD at the University of Chicago in 1951 at just 23 years of age. ‘No one was going to hire a kid to be a college professor at 23’, he said with wry pragmatism.

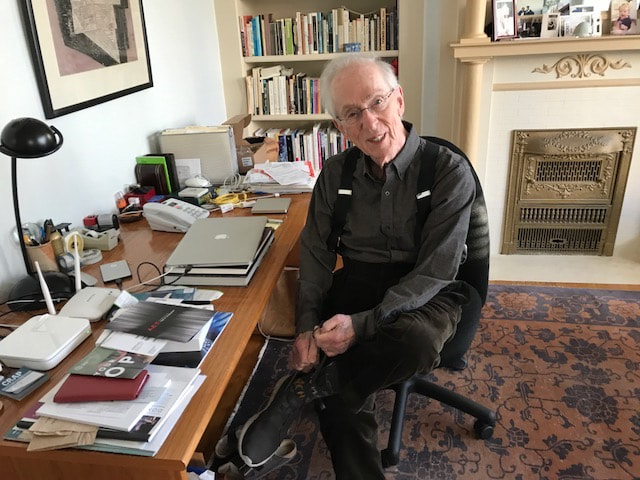

Howie and I had a long friendship. I visited him many times, and we recorded a series of interviews in about his life and work. I met Howie in 2014 at his home in Paris where he was living during the autumn and winter months. I asked him what he had learned from his life as a musician. ‘It did a lot of things for me, Les’, he explained. ‘One thing… it made me completely aware of the fallacies that are embedded in conventional thinking. I mean, when I read something like Talcott Parsons talking about “American values”, and I thought, which American values that he talked about are being enacted when I see the owner of the club give fifty dollars to a policeman? [Laughter] Because I would see that… Now not that all American values are like that but that has to be accounted for. It made me think that it (Parson’s way) is a ludicrous way to talk’. The world of the tavern was a ready-made ethnographic laboratory for fieldwork. What Becker learned from this experience was an alternative way to think about how norms and rules are applied. ‘I learned not to believe pious cant about how the laws embody eternal wisdom and the enforcers of the law are righteous activists working to make sure that eternal wisdom gets followed. I learned that by simple observation’. Many of the insights written in his classic study Outsiders (1963) are furnished by conversations that took place before gigs or exchanges that happened in breaks between sets. Later in our discussion I asked Howie whether musicians are more attentive. He dismissed the suggestion with dry and unsentimental precision: ‘Oh I don’t know, Les… you know there’s a lot of musicians who are not very attentive. They are just barely attentive enough’. We laughed and then he continued, ‘I think that’s a skill you know. You have to learn to pay attention; to me it’s a Zen lesson. That’s the basic lesson of Zen Buddhism: pay attention. Pay attention to what’s right there in front of you’. Howie continued, ‘There is a second part to this… See, one of the worst things that happens to sociologists is they become academics’. He then went on to cite an article written by his friend and colleague Harvey Molotch called Going Out (1994). In this article, Molotch argues that campus life insulates academics within what he calls our ‘taken-for-granted world’ that ultimately offers only a ‘thin slice of human experience’. Molotch calls for us to thicken our biographies by ‘going out’ or going ‘on the road’ and understanding the world ‘through its edges’. While musical life guarantees no special ear for society, it does make sociologists get out and about within its fringes. In the time-pressured environments of today’s university there is less time to go out and get off campus. That unsentimental sense of things combines both a sceptical but curious wonder. A life in music offered this to the sociologists quoted in my Identities article – Becker learned it from observing how things roll in the taverns of Chicago in the 1940s and 1950s from the vantage point of his piano stool. Read the Identities article: Back, Les. (2023). What sociologists learn from music: identity, music-making, and the sociological imagination. Identities: Global Studies in Culture and Power. DOI: 10.1080/1070289X.2023.2268969 OPEN ACCESS

Read further in Identities:

Looking through two lenses: reflections on transnational and translocal dimensions in Marseille-based popular music relating to the Comoros OPEN ACCESS ‘(What's so funny ‘bout) peace, love & understanding’: rock culture and the rebuilding of civic identity in the post-conflict Balkans ‘When breaking you make your soul dance’ Utopian aspirations and subjective transformation in breakdance OPEN ACCESS

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

|

Explore Identities at tandfonline.com/GIDE |

|

The views and opinions expressed on The Identities Blog are solely those of the original blog post authors, and not of the journal, Taylor & Francis Group or the University of Glasgow.