|

|

|

As socially committed and Spain-based researchers, we have long been amazed by the rhetorical power of the integration discourse (in this case, immigrant integration). This discourse has charmed and brought together people with different political orientations, even seducing numerous activists who usually adopt radically critical stances towards existing social oppressions (for example, capitalism).

However, such criticism does not frequently focus on integration. On the contrary, integration measures are often thought of as useful 'recipes' against racism, or even as its opposite. Hence, the 'benign' concepts associated to integration such as 'diversity', 'participation', 'active citizenship', 'interculturality', etc. have been often uncritically appropriated by non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and leftist movements, with allegedly inclusive or even anti-racist aims. The aim of our Identities article, ‘Elective affinities between racism and immigrant integration policies: a dialogue between two studies carried out across the European Union and Spain’, is to deconstruct such optimistic rhetoric, showing that racism and integration are closely embedded, and thus questioning the transformative potential of integration policies. With this aim, we have put into dialogue our PhD research pieces (one is complete, the other is being finalised), which respectively focus on the 'soft law' European Union framework for the integration of third-country nationals and Spanish/Andalusian immigrant integration policies.

0 Comments

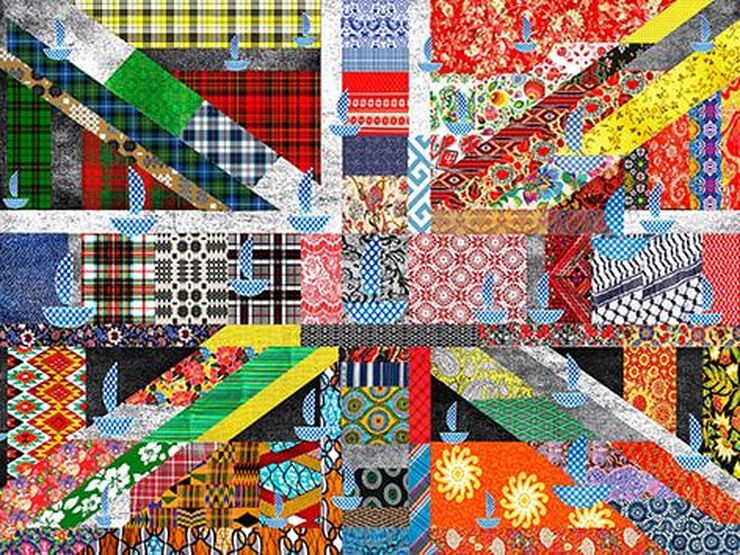

The illusion of Britain as a post-racial society, or at least a multi-cultural society at ease with racial mixing and mixedness that the royal wedding of Prince Harry and Meghan Markle conjured up, has been wiped aside by the couple’s revelation of the racism they had faced within the royal family, including questioning about the potential skin colour of their first born. Britain may have around one in ten of couples in a mixed relationship, but clearly this does not signal antiracist progress. Meghan will have dealt with overt and covert racism all her life, but it must have been a steep learning curve for Harry. What will this mean for how he seeks to bring up his son and soon-to-be born daughter?

In my Identities article, ‘Partnered fathers bringing up their mixed-/multi-race children: an exploratory comparison of racial projects in Britain and New Zealand’, I took an in-depth look at how fathers of mixed-race children sought to equip them to deal with racism, and give their children a sense of identity and belonging. Drawing on racial formation theory, I explored the individual racial projects that they pursued for their children, interacting with historical, social and political nation state racial projects.

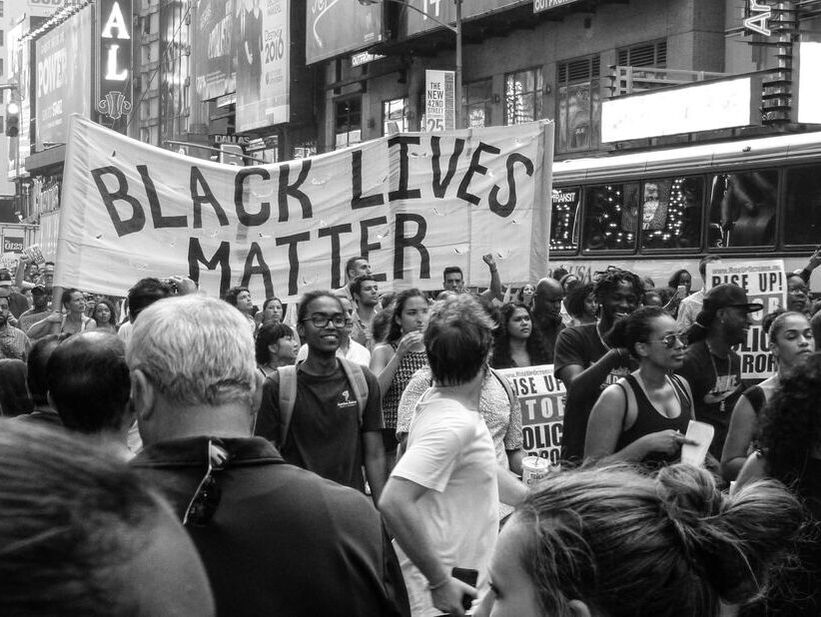

In this current moment where so many white individuals are contending with the implications of their racial privilege in the wake of the #BlackLivesMatter movement, it is important to understand the nuances of white identities. Much of the activism and effort over this past year has focused on urging white individuals to develop an awareness of the scope of racial inequality and white privilege. Less attention has been given to how white individuals might ethically deploy this racial understanding, especially regarding how white individuals might negotiate their participation within communities in which they are deemed racial outsiders.

My Identities article, ‘Ivory in an ebony tower: how white students at HBCUs negotiate their whiteness’, examines one such group of white individuals navigating their whiteness in a space where they are deemed racial outsiders: historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs).

Ken Carter, whose character inspired the realisation of the inspirational 2005 basketball movie, Coach Carter, decided to end the 1999 undefeated streak of Richmond High School basketball team because of his players' poor academic performance. His decision to lock the school gym and cancel the upcoming basketball matches, despite opposition amongst the Richmond community, garnered enormous US media attention framing it as an elevation of education over sports. While extensively elaborating and rationalising the gym shut-down in front of his students, Coach Carter posed a rhetorical question that resonates amongst recent events of police brutality and racial injustice in the US: where do these students end up after graduating high school? The answer for those who do not make it to college or into a professional sports career is, for many, probably prison.

Even though the US imprisonment rates have recently experienced its most significant decline in the last two decades, the Bureau of Justice Statistics (2018) data indicate that the US prison population's racial and ethnic makeup remains highly disproportionate to the actual demographics in the country. According to the US Justice Department, black Americans represent 33% of the sentenced prison population – a number nearly triple the 12% share of their US adult population. Even though the racial margin of incarceration has been in decline, black Americans constitute two times the rate of imprisoned Hispanics and slightly above five times the rate of imprisoned whites in the United States. Automatic transmission: how cars help us understand the dynamics of race and racialisation16/12/2020

In my Identities article, ‘Automatic transmission: ethnicity, racialization and the car’, I discussed how various types of racism can be transmitted through cars and roads, and feed into driver behaviour. While this can result in racial discrimination operating in formal and legal contexts, such as policing, racialisation through cars has a much broader, and at times, arguably banal, normative and taken for granted presence and reach.

In ethnically diverse towns and cities in the UK, when expensive cars are driven by young non-white males, what appears to be ordinary (driving and cars) becomes subject to racialised logic – that certain behaviours are tied to what become normative expectations of the ethnic group in question. In part, this happens because of what cars do and do not signify, but also, of course, this hinges on existing codes, stereotypes and ways of perceiving and explaining the idea of race, and all that flows from it. Earlier in 2020, we learnt that a number of prominent Black Britons, including MP Dawn Butler, had experienced, and subsequently spoke out about, racist policing. As distressing as such events are they are not particularly unusual; every day, black bodies are subject to similar, and worse, attention from law enforcement. In some cases, of course, the police may well have legitimate grounds to pull over a suspect, but often, it is the marker of race that helps prompt or even provoke the intervention.

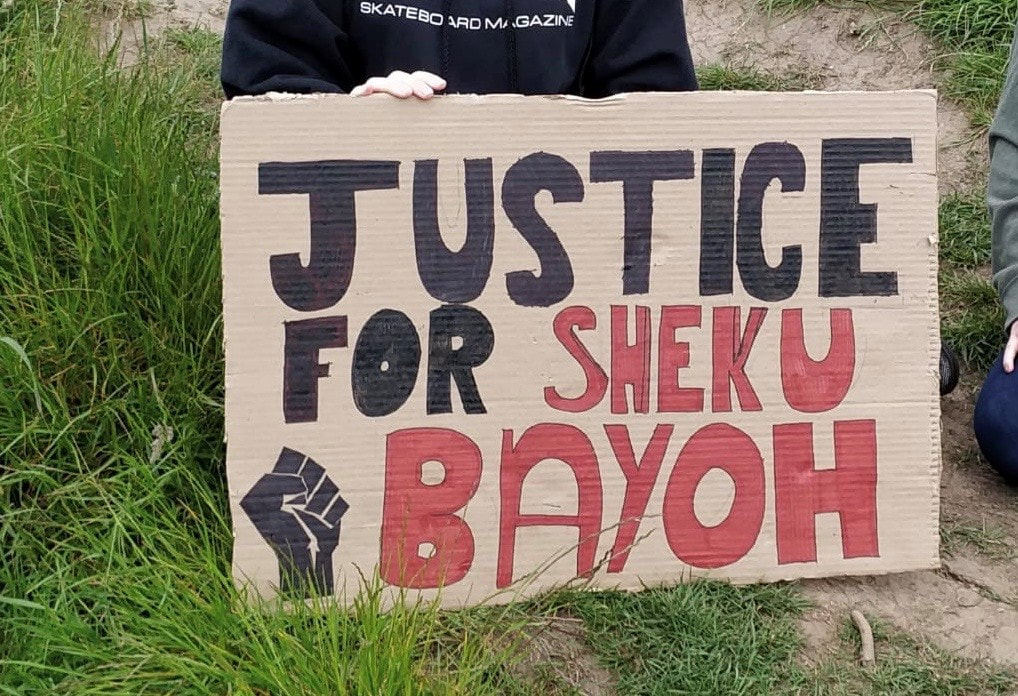

Sheku Bayoh died shortly after he was arrested by up to nine police officers in the early hours of 3 May 2015 on a quiet street in Kirkcaldy, a small town on the east coast of Scotland. Sheku’s mother had encouraged him to move to Scotland to be near his sister because she thought a young black man would be safer in Scotland than in London. CCTV footage has shown that Sheku was on the ground and restrained within less than a minute of police officers arriving, yet the postmortem revealed he had 32 injuries to his body. The Lord Advocate of Scotland announced in November 2019 that no police officer would be charged for Sheku’s death, four and a half years after Sheku died.

I wrote my Identities article, 'Containment, state racism and activism: the Sheku Bayoh justice campaign', not only to shed light on the circumstances of how Sheku died after he was arrested but to attempt to explain why deaths in police custody happen, why they are disproportionately of black people, and to develop an understanding of why the families who have lost loved ones find it so hard to get justice or even an adequate explanation from the police of why. I argue that the state has an interest in containing working class struggles and that state racism is used as part of the containment strategy that explains black deaths in police custody. I use a historical and theoretical analysis of how racism has been deployed by the state in immigration legislation where the black presence was problematised. The problematic black presence discourse has historically been a key feature of the policing of black communities – although this has evolved in several ways it nevertheless continues to produce a racial criminalisation of black people.

When writing public-facing policy-related reports, it is pro forma that the author(s) put forward a series of recommendations. Most of the time, writing recommendations is a data-/evidence-led process. What is more, some of the standard academic advice on writing recommendations includes things like ensuring that the recommendations speak directly to the aims and objectives of the project, acknowledging any limitations of the research and, where relevant, proposing further research. It also strikes me that writing recommendations can be an afterthought – a task left until the final full stop has been put on the conclusions.

Over the past seven years I have been involved in co-authoring reports on subjects ranging from the public impact of Irish Republican and Loyalist processions in Scotland, workplace racism, and more recently racism, institutional whiteness and racial inequality in higher education. Towards the end of this summer, I carried out a thematic analysis of the recommendations put forward in key government and non-governmental reports relating to racism and racial inequality in Britain on behalf of the Stuart Hall Foundation. Eight recurring themes emerged from the analysis of the 589 recommendations advanced in thirteen reports, ranging from the 1981 Scarman Report into the causes of the Brixton riots, through to David Lammy MP’s 2017 report ‘into the treatment of, and outcomes for Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic individuals in the criminal justice system’. Truth be told, this research was a depressing and blunt reminder that the recommendations put forward in reports are rarely ever acted upon, even though the report findings are typically greeted with performative enactments of shock, shame and concern. Indeed, the failure to act evidences a longstanding lack of political commitment to unsettling the coordinates of racial hegemony and disturbing orthodox ways of doing things. So much so, I am reminded of the words of the late Black novelist, playwright, essayist, poet and activist, James Baldwin, who once asked, ‘How much time do you want for your "progress?"’.

The themes of becoming and opposition as identification resonated with me, a white man from the US, as I searched for alliance strategies of anti-racism and anti-essentialism in historically the most creolised part of Europe: Portugal, and more specifically, the capital city of Lisbon.

I had spent the better part of the late 1990s and early 2000s with hip-hoppers, mostly young men of African-Indigenous descent, in the working-class neighbourhoods on the outskirts of São Paulo, Brazil, and considered myself relatively prepared to approach the former metropole of Lisbon as a 'Black' city. During research stints from 2007 to 2013, I realised that the spatial dimensions and historical depth of Blackness were much more complex than I originally had appreciated. In particular, local creole-speaking rappers in Lisbon, Portugal, who identify as Cape Verdean, sometimes Portuguese, sometimes African, occasionally European or even American, tuned me into the predicament and potential empowerment of Blackness: Black time depends on Black space; Blackness as encounter. Understanding racial capitalism in Africa: a study of the Nigerian oil-dependent capitalist economy21/10/2020

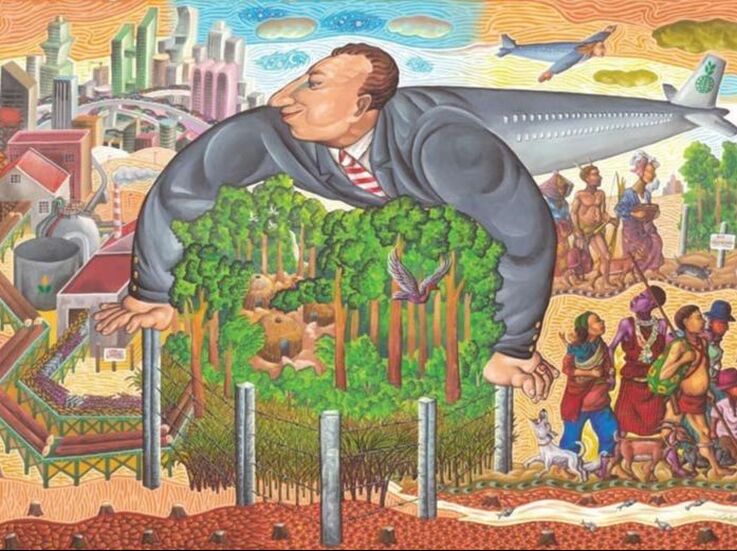

My Identities article, ‘The capital, state and the production of differentiated social value in Nigeria’, problematises the Nigerian oil-dependent capitalist economy through the perspective of the Black radical tradition. Using Cedric Robinson’s concept of race, I analyse the racialism inherent in the Nigerian capitalist economic relations and the accompanying contradictions. Capitalism is a very powerful historical force that has influenced and still influences diverse social, political and economic landscapes. The state is an agency through which the association of individuals are entrusted with the administration of the affairs of a given society. Both the capital and state are essential agencies in the entrepreneurial model of the capitalist mode of production.

Marxist scholars present capitalism as an unfair system that engages in unequal distribution of the social wealth generated by the society. Marx argues that the capitalist society is divided along class line and the economic factor remains the most decisive determining factor in shaping capitalist dynamics and its contradictions, while culture and other human pre-occupations play a role but not the decisive one. The working class, Marx maintains, is the revolutionary class that will eventually transform the capitalist economy. COVID-19, BAME communities and local football: can local BAME football win against COVID-19?16/9/2020

On 26 May 2020, professional football in England resumed after a three-month shutdown in response to the COVID-19 outbreak in the UK. The disproportionately high COVID-19-related mortality rates among Britain’s black, Asian and minority ethnic (BAME) communities prompted some debate among football professionals, journalists and academics as to the potential higher risk ‘project restart’ posed for black professional footballers compared to their white peers (Minhas et al, 2020). Nonetheless, the launch commenced, and fears were alleviated (initially at least) by the implementation of a robust test, track and trace system and by clubs operating extraordinarily high levels of surveillance and control over their players’ daily activities.

On 12 September, the Football Association in England (FA) ‘restarted’ the non-professional format of the game. By comparison, there has been much less public scrutiny of this roll-out, and especially in relation to broader questions around public health. Or to the potential of local football to contribute to the disproportionately high COVID-19 mortality rates among Britain’s minority ethnic communities. The absence of debate is quite remarkable given that, according to the FA, there are currently over 3,000 non-professional women’s, men’s, youth and mini-soccer football clubs that play on a ‘Saturday’ across England, compared to just 92 professional clubs. This is also surprising given the long history and relationship between local football and Britain’s BAME communities.

'There are no Asians in Asia, only people with national identities, such as Chinese, Japanese, Korean, Indian, Vietnamese and Filipino. But on this side of the Pacific, there are Asian Americans', wrote the historian Ronald Takaki. This quote juxtaposes the diversity and heterogeneity of individuals in Asia with the American reality of their pan-ethnic conflation.

In my recently published Identities article, 'There are no Asians in China: the racialization of Chinese international students in the United States', I explore this idea empirically with a longitudinal study of Chinese international students and their racialisation in the United States. I argue that it is through a process of racialisation – a process that involves learning about the concept of 'race' and one’s own social categorisation under such a paradigm – that those arriving from a country like China or Japan could eventually come to identify as 'Asian' or 'Asian American'. My study draws on two-stage interviews with 15 Chinese international students. The first interviews were conducted within two weeks of their arrival in the United States. I did so in order to capture the Chinese students’ initial understandings of race and their racial identities, before much acculturation processes could take place. I found, not surprisingly, that most Chinese students at this stage identified strongly with their national identity as Chinese and dismissed the category 'Asian' as a label of little significance to them.

If we are to assume the Shakespearean platitude that 'the eyes are the windows of the soul', then it is not beyond our comprehension that visual images used by NGOs (non-governmental organisations) in their advertisements are carefully curated ideas over who or what is ‘seen’, and more importantly ‘how’ it is seen, and for whom. In today’s progressively changing and competitive media and communications environment, humanitarianism is now a profitable enterprise in our visual-as-currency economy.

On our television screens, in our social media applications and unsolicited pop-up email advertisements, and even among the rumpled pile of outdated magazines in the doctor’s waiting room, the public faces of the international aid and relief industry are seldom out of sight. Whether it is malnourished pot-bellied toddlers wearing western football memorabilia of seasons past, a despondent refugee mother in a displacement camp, or a vast horde of shaven-headed, undifferentiated Black and Brown masses in conflict zones, these images are the aesthetic currencies of commercialised suffering employed by humanitarian organisations to brand themselves and their strategic ambitions, and imbue western audiences with a philanthropic disposition. Visual representations are central to – and orbit around – the phenomenon and work of humanitarianism. When we think of humanitarian work, we often visualise much of the non-western, Black and Brown world. As image producers and disseminators, these organisations set the visual tone within which certain people and places are defined and comprehended – indeed, who (and what) they ‘are’, ‘aren’t’ and ‘ought to be’.

Henri Lefebvre and C.L.R. James were quintessential twentieth-century intellectuals. They were born within six months of each other in 1901. Both lived to within sight of the century’s end: James died in 1989 and Lefebvre in 1991. And, as I argue in my Identities article, 'Passing through difference: C.L.R. James and Henry Lefebvre', their grappling with the times in which they lived led them to articulate a comparable politics.

What kind of politics? One which valued human flourishing more than formal equality. One which considered creative freedom more significant than technological progress. And one which found hope in the way in which ordinary people fought against constraint in their day-to-day lives.

Boxing fans and pundits might be familiar with the term 'undisputed' champion. Reserved mainly for boxers, the 'undisputed' champion is seen as the unquestioned champion of (mainly his) weight division. To achieve this status, he must become champion of the various worldwide boxing organisations. Of course, the boxer must constantly defend this status over and over again in order to maintain his place atop the boxing hierarchy. In other words, being an undisputed champion is fleeting, unpredictable, and always in flux.

In my Identities article, ‘Undisputed’ racialised masculinities: boxing fandom, identity, and the cultural politics of masculinity', the term 'undisputed' is repurposed to theorise and allegorise how it is fraught with contradictions. My findings highlight how the undisputed status of racialised masculinity is constantly struggled over, negotiated and contested by male boxing fans of colour. Based on fieldwork observations during a Manny 'Pac-Man' Pacquiao vs. Juan Manuel Marquez boxing match in 2011, interviews conducted with 1.5 and 2nd generation Filipina/o Americans, and close analysis of 'Gayweather,' it analyses how male fans of colour seek an undisputed masculinity in complex and problematic ways. Handsworth and the production of knowledge: Blackness, racism and anti-imperialism in 1970s Britain27/11/2019

The African Caribbean Self-Help Organisation (ACSHO), based at Heathfield Road in Handsworth, Birmingham, established itself as a central hub for Pan-African centred learning and intellectual debate in the early 1970s. ACSHO members were part of a UK-wide co-ordinating committee that sent a delegation of activists to the 6th Pan African Congress (6PAC) in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania in 1974. My Identities article, ‘Each one teach one’ visualising Black intellectual life in Handsworth beyond the epistemology of ‘white sociology’, shows how the conference statement by the UK delegation at the 6PAC meeting was critical of the inherent racism of their social condition in England’s metropolitan cities as well as of the racist ways they were being studied by white social scientists at the time. Through their own Pan-African centred and anti-colonial critique, the delegation used ‘scientific socialism’ to situate their political struggle within a global context of anti-imperialist resistance movements.

Inside this hive of Black intellectual activism emanating from Birmingham, the archival work of Vanley Burke is particularly noteworthy. Born in St Thomas, Jamaica in 1951, Burke recalls receiving a gift of a camera sent by his mother from England for his 10th Birthday. He became fascinated by the ‘magic of photography’ and was compelled by both the science and artistry of this medium (Sealy 1993). Since the early 1970s, Burke has documented the lives of Caribbean communities in Birmingham with an intimacy and sensitivity towards the people he shares the city with.

A couple of years ago, I shared a paper-in-progress with some colleagues. I got a lot of wonderfully kind and collegial feedback, but I noticed that something was amiss between my own home base of sociology and other disciplines that theorise emotion. At the mere mention of the name Lauren Berlant, two people reeled back in their chairs, rolling their eyes and groaning in exasperated derision. The centring of Stuart Hall's work in my paper perplexed one colleague, who explained that 'we've transcended Hall with Pierre Bourdieu and Jeffrey Alexander'.

Bourdieu and Alexander, I couldn't help noticing (especially by contrast to Hall), are decidedly less adequate for understanding race and, to a lesser extent, gender. And unlike Bourdieu and Alexander, who are claimed in the name of sociology, Hall and Berlant can be considered cultural theorists, though they've significantly influenced social theory. The encounter I've just described sits where these two terrains of struggle meet: disciplinary politics and politics more broadly. I want to suggest that it would be fitting to bring the same principles that guide better political praxis into our inter/disciplinary engagements. The haste with which some sociologists of emotion dismiss interdisciplinary fields such as cultural studies, critical race studies, and postcolonial studies is in one sense perhaps not surprising. Despite the significance of emotion in the organisation of every aspect of social life, keyword searches for recent publications on emotion within prominent journals in these fields produce surprisingly scant results. Other concepts, such as 'attitudes' and 'lived experience', feature more prominently. For emotion theorists seeking an excuse to bypass interdisciplinary work, the lexical differences seem sufficient. 'There's nothing relevant for me here. This isn't how “we” do it.'

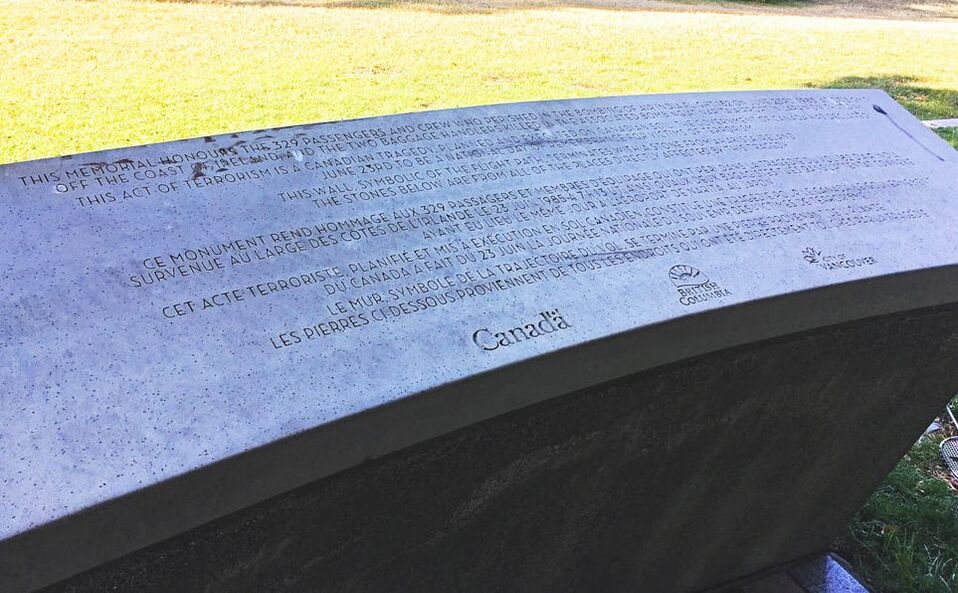

In June 1985, 331 people were killed in the bombings of two Air India flights, which investigators attributed to militant Sikh nationalist groups operating in Canada. Although the bombings are now regarded as the deadliest incident of terrorism in Canadian history, they continue to hold a complex, often contradictory place in Canada’s imaginary.

Much of the existing scholarship has attributed this complexity to systemic racism that limits how the bombings have been regarded and remembered as a ‘Canadian tragedy’ (Dean 2012, Failler 2009, Seshia 2012), even as the Canadian government devoted considerable resources to investigating and prosecuting the attacks. In 2006, the Government of Canada even commissioned a public inquiry to determine how state institutions failed to prevent and effectively prosecute the bombings. Given that the inquiry received evidence that systemic racism shaped state responses to the bomb plot, it offers a unique vantage point to examine how state institutions reckon with their implication in racial violence. 25 years after apartheid: are British-born South Africans signing up to the ‘rainbow nation’?2/10/2019

2019 marks 25 years since Nelson Mandela was elected as the first black president of South Africa. Finally, apartheid, the system of racial segregation institutionalised by the Afrikaans-led Nationalist Party in 1948, was a chapter closed. Since that time, South Africans of all backgrounds have been debating the extent to which the post-apartheid vision of ‘a rainbow nation’ -- a multicultural unity of people of many different nations -- is being realised.

This question is not only of interest and importance within South Africa. Against a context of rising populism and white nationalism across the Global North, are white people in South Africa really rejecting the privileges of white supremacism which they have enjoyed for so long? My Identities article, 'Reimagining racism: understanding the whiteness and nationhood strategies of British-born South Africans', examines this question by looking at one group of South African Whites: those who were born in Britain and migrated to South Africa. Many did so in the 1960s, 70s and 80s, through a ‘Ten Pound Pom’ scheme which offered them cheap passage, good jobs and comfortable accommodation on arrival. Whereas, at home in Britain, there was rising rejection of the apartheid system in South Africa, this group chose to up sticks and move to a deeply segregated society. How do they explain this, to others and themselves? And how do they now talk about the situation in South Africa today?

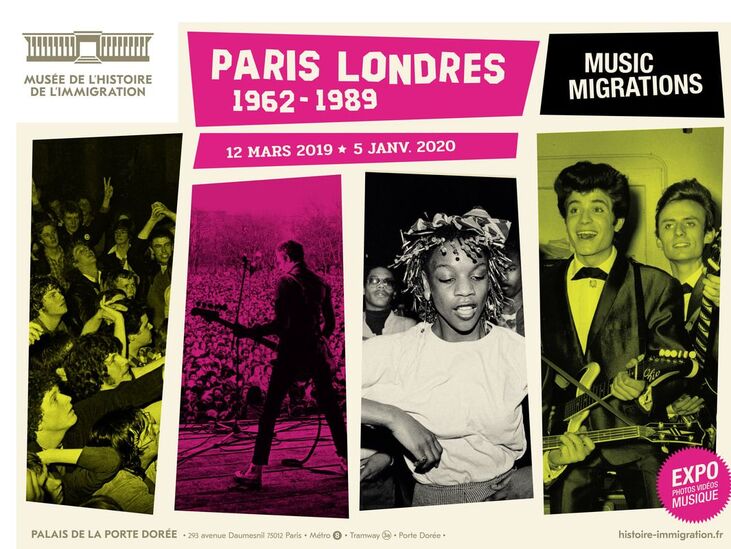

In 2019, Musée d’Orsay held an exhibition on Black Models, and the National Museum of the History of Immigration held a year-long exhibition on the musical contribution of migration to Paris and London. Why do we need a specific show to give black models an identity and an exhibition to demonstrate the contribution of post-colonial migrants to popular music?

In my Identities article, 'The whiteness of cultural boundaries in France', I explore the underpinnings of France’s relationship to the culture of the Other, through the scope of whiteness. I contend that whiteness can be defined as a kind of capital embedded in the routine structures of economic and political life and is therefore a relevant concept to analyse French cultural policy.

On April 15, 2013, two pressure-cooker bombs exploded at the finishing line of the Boston Marathon, killing five and injuring 264. In the absence of information about who the bombers were, Salon.com published liberal commentator David Sirota’s piece 'Let’s Hope the Boston Marathon Bomber is a White American'. Sirota argued that if the bombers turned out to be white, Muslims would be protected from an inevitable anti-Muslim backlash. A few days later, the bombers’ identities were revealed as brothers Tamerlan and Dzhokhar Tsarnaev, children of Chechen refugees who came to the United States when they were 16 and 8 years old, respectively. Interestingly, the brothers were phenotypically white and, as conservative commentators online were fond of saying, quite literally Caucasian (i.e. from the Caucuses). They were also, however, Muslims.

Sirota’s article provoked a firestorm across conservative media, and Sirota was accused of being race obsessed and blind to the threat of Jihadist terrorism. In our Identities article, '‘Let’s hope the Boston Marathon Bomber is a White American’: racialising Muslims and the politics of white identity', we analysed conservative responses to Sirota’s article, as well as the ensuing debate about whether the Tsarnaevs were, in fact, the white Americans Sirota had hoped for.

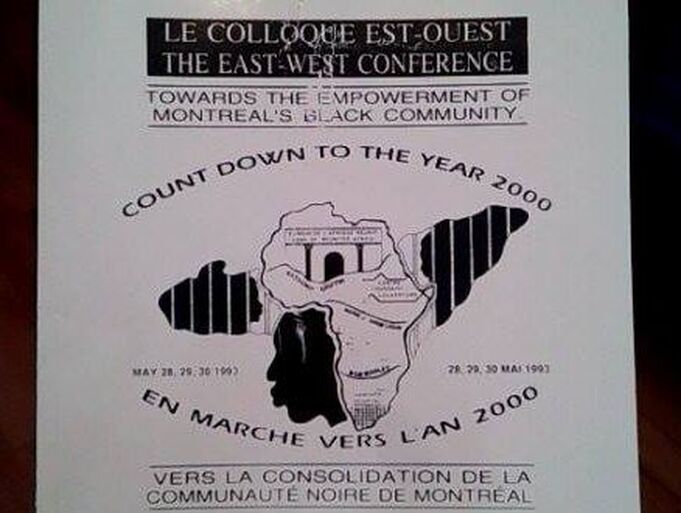

While tourists know Montreal for its cafés, festivals and old-word European 'charm'*, locals also know its boundaries that divide the city into an Anglophone West and a Francophone East. Montreal’s Black community usually occupies space according to this prevailing language divide: Black Francophones on the East side, and Black Anglophones on the West side. This pattern has had implications for relationships among Black Montreal residents, as well as for their organisation and political possibilities. Indeed, after the rise of Quebec nationalism starting in the 1960s -- which made the French language 'the distinguishing characteristic of ethnic identity' (Thomson 1995) -- it has been somewhat challenging for Black people to organise as Black people, rather than linguistically-specific 'Anglo' and 'Franco' Black communities.

Adding to the rich literature on how space and place are inherently racially produced and lived, my Identities article, 'Black in the city: on the ruse of ethnicity and language in an antiblack landscape', helps to elucidate how the politics of language and ethnicity do not occlude the ways in which race and antiblackness configure the city.

How much should biology matter to our identities? When it comes to race and ethnicity, many people believe there are biological differences between groups. Actually, despite what many think, geneticists have proven that all humans are more than 99% genetically similar regardless of race. Even though these discoveries made in 2000 were widely reported in the news and in academic settings, most people (including academics!) continue to use assumptions that biology is relevant to determining who we are and to what groups we belong.

In today’s society, many people believe they are 'colourblind' and that we are 'post-race' — in other words, they think race shouldn’t matter anymore, that racism is a thing of the past, and that everyone has an equal chance at succeeding in society. Another part of 'colourblind' thinking is that we have changed the way we talk about race. Today it is far more common to use code words such as 'illegals', 'inner-city', or even to talk about culture as a stand-in for talking about racial groups.  Photo credit: Jason Tester Guerrilla Futures. CC BY-ND 2.0. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nd/2.0/. Photo credit: Jason Tester Guerrilla Futures. CC BY-ND 2.0. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nd/2.0/.

The narratives presented in British public debates around terrorism have been long rooted in notions of increased presence of Islam in the public square as intuitively resulting in greater risk to the public. The most significant question this raises is who the ‘public’ refers to when discussing issues around securitisation. The recent horror of Christchurch represents something of an inverted scenario with the positioning, and following it we saw a series of Islamophobic attacks on mosques in Birmingham.

The connection between global and local events is significant because it explicitly requires us to engage in a process which, we argue in our Identities article, 'Securing whiteness?: Critical Race Theory (CRT) and the securitization of Muslims in education', is often absent. Our purpose in the article was to explore some of the ways in which Muslim communities are racialised and instrumentalised, rather than protected. Getting to grips with how Muslims have been located as stakeholders in national security in Britain is revealing. A large part of the Prevent counter-terror strategy relies on partnerships with Muslim communities. So in many senses British Muslims are the key stakeholder group in the securitisation process -- so how does it play out for them? How are their interests reflected in exchange for engaging in these partnerships with the state?

'First, I'll need tenure. And a big research grant. Also access to a lab and five graduate students — at least three of them Chinese.'

- Professor Ogden Wernstrom, Physicist Those are Professor Ogden Wernstrom’s demands when asked to save the Earth from a giant garbage ball approaching through space in the Futurama episode, A Big Piece of Garbage. Portrayed as an obvious antagonist, Wernstrom seems greedy and exclusively concerned with his own career advancement. He also seemingly regards grad students as just another commodity to further his own goals, with Chinese students as particularly valuable or useful assets. This specific view on Chinese researchers as not much more than pricey pieces of high-tech equipment was provided by a cartoon villain 20 years ago, but it arguably still falls into the questionable category of 'it’s funny because it’s true': it indeed resonates with prejudices that extend beyond the Futurama universe and into real-world academic discourse.

When you see images of French daily life or French people in magazines, films, or other media, what do you see?

Usually, it’s white people, with perhaps a few visibly non-white people depicted. But this is odd for multiple reasons. One, France has a long history of immigration, primarily from its overseas territories and former colonies. Due to years of colonialism, colonial slavery, and subsequent migration, ethnic minorities, or 'visible minorities' in French academic parlance, have long been part of French society. Secondly, France does not acknowledge or measure race as a separate identity category. So while France is a multicultural society, it does not, as a facet of law, distinguish between these different cultures. One is either French or not. This is France’s Republican model. |

|

Explore Identities at tandfonline.com/GIDE |

|

The views and opinions expressed on The Identities Blog are solely those of the original blog post authors, and not of the journal, Taylor & Francis Group or the University of Glasgow.