|

|

|

On 8th September 2021, a crowd gathered on Monument Avenue in Richmond, Virginia, USA, near the base of its iconic statue of Confederate General Robert E. Lee. The atmosphere in the crowd was jubilant as workers positioned a crane, wrapped the statue in a harness, and finally–after an hour of preparation, a year of court cases, and 131 years of racial terror set in stone–pulled the statue down from its plinth.

The equestrian statue of Robert E. Lee, Commander of the Confederate Army, is, and always has been, a symbol of white supremacy. Its removal creates the opportunity to change the meaning of the space it once occupied. For the past year at the Centre on the Dynamics of Ethnicity (University of Manchester), we have interviewed activists, policymakers, and cultural workers involved in contesting fourteen statues of slavers and colonisers in five countries. We have also explored the meanings of statues of empire and colonialism with young people from Manchester Museum’s OSCH Collective who shared how statues of white supremacy in towns and cities they call home impacted their sense of belonging. Our research highlights how anti-racist activists draw from global movements to contest local histories and memories. Equally, we consider how strategies for removing Confederate statues in the US (for example) might provide lessons for challenging imperial statues in the UK.

Our ESRC funded project, ‘The Changing Shape of Cultural Activism’, featured Lee’s statue on Monument Avenue as one of our case studies. Monument Avenue itself was a planned, all-white community, constructed in the late nineteenth century near (and in response to) the thriving Black, middle-class neighbourhood of Jackson Heights. On many maps of Richmond, Lee Circle is in the centre. This reflects the centrality of the street to Richmond’s dominant, post-Civil War idea of itself as a site of memory for the Confederacy, and the home of the ‘Lost Cause’ mythology. It was also meant to instil terror in Black Richmonders.

Key to that message was the statue itself: sculpted by Antonin Mercié in France and shipped to Virginia in 1890, it was four meters high and sat atop an imposing fourteen-meter plinth. Lee’s was the first statue to be installed on Monument Avenue, but it launched a flurry of Confederate statue-building in Richmond between 1891 and 1929. Eventually, the street would boast statues of Confederate President Jefferson Davis, General Stonewall Jackson, General J.E.B. Stuart, and Commander Matthew Fontaine Maury. The timing is noteworthy: a generation after the end of the Civil War, and in the thick of Jim Crow, the erection of the statues sent a clear message that white supremacy still reigned in Richmond. That message, however, was contested from its earliest days. Consider John Mitchell Jr., the African-American editor of the Richmond Planet and a member of the City Council, who wrote on 31 May 1890 about the statue’s inauguration: ‘The South may revere the memory of its chieftains. It takes the wrong steps in so doing, and proceeds to go too far in every similar celebration. It serves to retard its progress in the country and forges heavier chains with which to be bound.’ Forty years later, reflecting on the proliferation of Confederate statues across the South, W.E.B. Du Bois wrote: The most terrible thing about war, I am convinced, is its monuments,–the awful things we are compelled to build in order to remember the victims. In the South, particularly, human ingenuity has been put to it to explain on its war monuments, the Confederacy. Of course, the plain truth of the matter would be an inscription something like this: ‘Sacred to the memory of those who fought to Perpetuate Human Slavery.’ But that reads with increasing difficulty as time goes on. It does, however, seem to be overdoing the matter to read on a North Carolina Confederate: ‘Died Fighting for Liberty!’ (‘The Perfect Vacation’, The Crisis August 1931, p. 279)

Intermittent efforts to dampen the street’s association with the Confederacy–most notably, the erection of a statue of African-American tennis player Arthur Ashe in 1996–did little to alter the meaning of the existing statues.

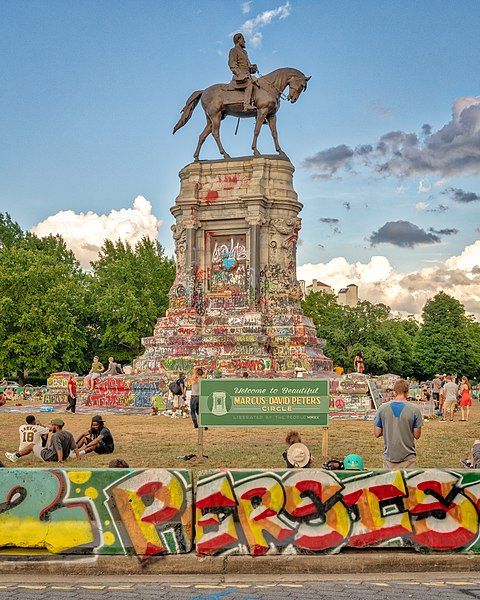

In the 21st century, Monument Ave was still effectively a no-go zone for many African-Americans. Several lifelong Richmonders we interviewed said that they deliberately took alternative routes to avoid the street. It was embarrassing and irrelevant to the Richmond they knew. It was a proclamation that they were unwelcome. In case there was any doubt about the meaning of the statue, groups of neo-Confederate ‘flaggers’ descended regularly on Lee Circle. In April 2017, Mayor Levar Marcus Stoney stated that the monuments should be ‘contextualised’, and launched the Monument Avenue Commission. But he stopped short of calling for the removal of the statues, and for that he was widely criticised by the NAACP and local anti-racist activists. For example, Ana Edwards and Phil Wilayto of the Virginia Defenders of Freedom, Justice & Equality published an op-ed in the Richmond Free Press recounting the history of Confederate monuments in Richmond and the gradual transformation of the city into a ‘virtual shrine to the Lost Cause mythology’. Because of the cult of white supremacist memory, and because of its longstanding contestation, it was particularly significant that Lee Circle became the locus of Black Lives Matter protests in June 2020. The protesters reclaimed the epicentre of white supremacy in Richmond, renaming it in honour of Marcus-David Peters. They engaged in a plethora of creative actions: Dustin Klein and Alex Criqui projected George Floyd’s image onto the plinth; protestors climbed on the plinth and covered it with colourful graffiti; ballerinas posed there with raised fists. It was because of this anti-racist social movement that Mayor Stoney changed course and ordered the removal of Richmond’s Confederate statues. The Richmonders we interviewed were virtually unanimous in their desire to bring the statue down. Yet they expressed many different ideas about what should happen next. Replacing Lee with another statue–or a garden, or a fountain–is tempting. Doing so, however, could also close off the tremendous creative energy of collectively reclaiming the circle. Perhaps the empty, graffitied, reclaimed plinth should stay where it is, as a reminder of the movement that brought Lee down and a call to keep reclaiming space.

Blog post by Meghan Tinsley, Sadia Habib, Chloe Peacock, Ruth Ramsden-Karelse and Gary Younge

Cross-posted by RACE.ED.

Read relevant Identities articles:

The afterlife of insurgency: dissent, dialogue, decolonisation Situating sugar strikes: contestations of race and politics in decolonizing St. Lucia The wreckage of white supremacy

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

|

Explore Identities at tandfonline.com/GIDE |

|

The views and opinions expressed on The Identities Blog are solely those of the original blog post authors, and not of the journal, Taylor & Francis Group or the University of Glasgow.