|

|

|

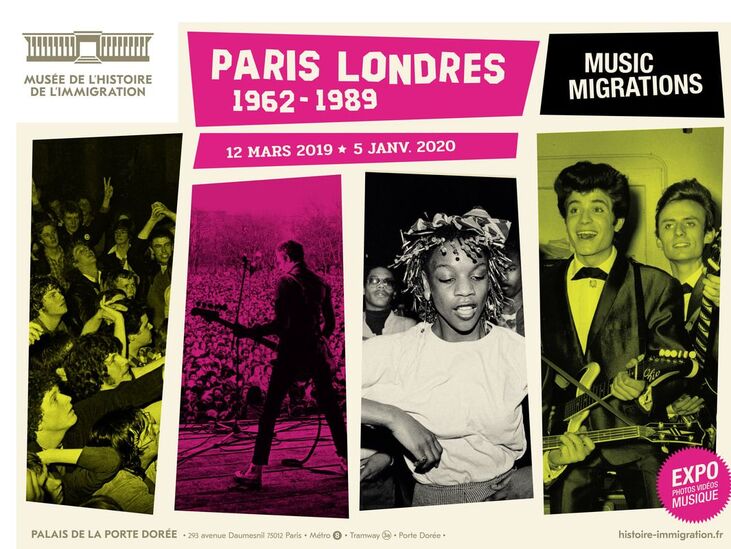

In 2019, Musée d’Orsay held an exhibition on Black Models, and the National Museum of the History of Immigration held a year-long exhibition on the musical contribution of migration to Paris and London. Why do we need a specific show to give black models an identity and an exhibition to demonstrate the contribution of post-colonial migrants to popular music?

In my Identities article, 'The whiteness of cultural boundaries in France', I explore the underpinnings of France’s relationship to the culture of the Other, through the scope of whiteness. I contend that whiteness can be defined as a kind of capital embedded in the routine structures of economic and political life and is therefore a relevant concept to analyse French cultural policy.

I start with the creation of a French Ministry of Culture in 1959 and show that it was not that Culture Minister André Malraux and his colleagues were not interested in foreign culture, but rather that their universalist approach to foreign arts prevented them from considering the cultural dimension of the growing presence of immigrants in France. Over the decades, immigration transformed from an economic phenomenon to a cultural matter, and in this process, French cultural policies became perceived as a useful tool to integrate newcomers. In the 1970s, the French Labour Ministry subsidised the television show Mosaïques that broadcasted images of immigrants’ country of origin, setting a clear boundary between France and the country where they came from. In the 1980s, the French Ministry of Culture marvelled in the creative power of a generation of immigrant offspring and used it to celebrate French cultural diversity.

However, based on an analysis of the archives of the Ministry of Culture and several interviews with administrative officials, I discovered that migration-related minorities mostly have to justify the social benefit of their artistic initiatives. The administration’s reliance on cultural policy to solve matters related to perception of immigration in political opinion shows that cultural policy serves to negotiate boundaries in France. In defining specific guidelines for the implementation of cultural programmes aimed at immigrant integration, administrative officials treat immigrants and nationals differently. This point is not to be missed by numerous immigrant artists or immigrant groups who criticise this double standard treatment. How is it that when a group of immigrants has an artistic project, they have to meet some specific guidelines that are not based on artistic value but on the project’s implication in terms of social development? The differential treatment due to migration-related artistic projects allows us to identify the privilege embedded in the routine structure of cultural life: the privilege is to be evaluated according to the impartiality of aesthetic criteria, as opposed to having to justify for its social impact. This set a clear boundary between natives and migration-related minorities: the privilege of the majority is to be able to define culture in universalist terms, when minorities are constrained with end goals. The concept of whiteness can help us reframe the discussion around inequality and difference. Instead of focusing on systems of stigmatisation, it helps us shift our focus on the reverse: the definition of privilege. The lack of clear determination of what culture means in connection with immigration comes through as striking evidence of an asymmetrical relation.

Blog post by Angéline Escafré-Dublet, Université Lumière Lyon 2, France

Read the full article: Escafré-Dublet, Angéline. The whiteness of cultural boundaries in France. Identities: Global Studies in Culture and Power. DOI: 10.1080/1070289X.2019.1587906

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

|

Explore Identities at tandfonline.com/GIDE |

|

The views and opinions expressed on The Identities Blog are solely those of the original blog post authors, and not of the journal, Taylor & Francis Group or the University of Glasgow.