|

|

|

It was an improbable scene: I was using the photocopiers at the National Library in downtown Singapore, and a smartly dressed young man from Bangladesh walked in with a coffee table book featuring the city. We talked; he needed help to get a colour copy of a shot of the Singapore skyline. He wanted to send the picture back to his family, to tell them with pride he was here and helped build this great city.

It was improbable for him, a foreign worker, to be in the privileged space of the National Library and for I, a privileged citizen, to be chatting about life with him. But there it was. After all, Singapore is a multiracial nation. The Chinese make up three-quarters of the population, with Malays and Indians making the rest. Singapore is also a cosmopolitan global city. Citizens make up three-fifths of the population. A vibrant mix of migrants and resident workers from around the world – all highly skilled – leavens the economy of advanced manufacturing and services. They make the city more than multicultural: Singapore is super-diverse. But, as I discuss in my Identities article, ‘Super-diversity and the bio-politics of migrant worker exclusion in Singapore’, there is another face to super-diversity.

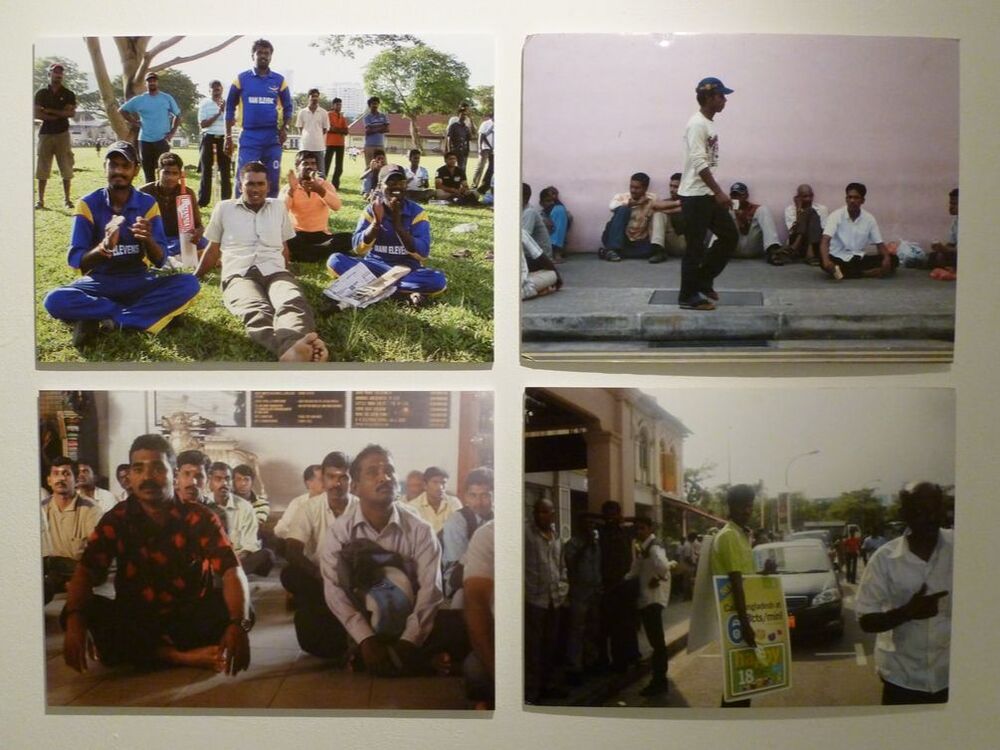

The large majority of the remaining two-fifths of Singapore’s population are guest workers, most of them low-wage male workers from South Asia and female domestic workers from Southeast Asia. Over the years, the male foreign workers who build and clean the city have been pushed out from public housing estates where four-fifths of Singaporeans live. They are increasingly pushed into large dormitories situated in industrial areas and the margins of the city.

Space crunch in land-scarce Singapore meant that there were occasions foreign workers were temporarily housed near residential estates. This has provoked controversies, the most vivid of which involved the sitting of dormitories in disused public buildings such as old schools, close to upper middle-class landed estates. Amid worries that the presence of foreign workers in their neighbourhoods would affect property values and that the workers would fraternise with their female domestic workers, this conservative class of citizens rose in protest: ‘Not in my backyard!’ Unable to move the workers, the authorities responded to the tensions by building fences and organising citizen patrols to keep the foreign workers away from the estates as much as possible. Rules included the prohibition of wearing sarongs outside the dormitory, urinating in public, littering and being too noisy. Offenders were fined around a tenth of their salary. Beyond the middle-class landed estates, large groups of foreign workers occupying town centres, and the common spaces of public housing estates in the evenings and Little India during the weekends, drew complaints from citizens. The government built regional recreational centres filled with eating places, grocery shops and sports facilities near dormitory clusters to try to draw the workers away from town centres. The Little India riot in December 2013 catalysed the growing exclusion of foreign workers from the global city. Upset after an intoxicated worker was knocked down and killed by a bus that took the workers back to their dormitories, a few hundred workers attacked police and rescue personnel, and set emergency vehicles ablaze. The authorities became keenly aware of the danger of over a hundred thousand foreign workers packed into the downtown heritage precinct of Little India every weekend. The authorities accelerated the building of mega-dormitories in outlying peri-urban areas with the capacity to house tens of thousands of foreign workers. They were to be well provided for. Mass kitchens, recreational facilities and shops catering to the needs of the resting workers meant they did not have to travel the long distance to Little India. More regional recreational centres were built, for those who still felt the need to travel out. Indeed, defining and meeting needs became the key to exclude the foreign workers from the city and its super-diversity.

Blog post by Daniel P.S. Goh, National University of Singapore, Singapore

Read the full article: Goh, Daniel P.S. Super-diversity and the bio-politics of migrant worker exclusion in Singapore. Identities: Global Studies in Culture and Power. DOI: 10.1080/1070289X.2018.1530899

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

|

Explore Identities at tandfonline.com/GIDE |

|

The views and opinions expressed on The Identities Blog are solely those of the original blog post authors, and not of the journal, Taylor & Francis Group or the University of Glasgow.