|

|

|

On 10th May 2022, plans to legislate for the Irish language in Northern Ireland were announced in the Queen's Speech at the State Opening of the Westminster Parliament. The speech pledged a new Irish Language Commission, designed to “protect and enhance the use of the Irish Language”. The bill will also establish a new Office of Identity and Cultural Expression. This will offer guidance to public authorities on a range of cultural identity principles that were set out in the 2020 New Decade, New Approach document. The bill will also place a duty on the Department of Education in Northern Ireland facilitate and promote Ulster-Scots in education.

On 25th May 2022, the Secretary of State for Northern Ireland introduced legislation in Westminster that will deliver this package of measure. Irish speakers have reacted with cautious optimism, but have also warned that the Bill needs to be enacted and implemented in full before they will end their campaign in support of a language act.

Ongoing tensions regarding the challenge of language use in a post-conflict site, such as Northern Ireland, is the focus of our new contribution to Identities, 'Intracultural dialogue as a precursor to cross-community initiatives: the Irish language among Protestants/unionists in Northern Ireland'. Arguing that language issues are far more important than is generally recognised for stability in a post-conflict region, we observe how debates on language rights are often framed around a political and ethnic divide which belies the more complex realities of identities among the population. Such interpretations fail to acknowledge the existence of small groups and individuals who engage with and learn a language not ordinarily associated with their own political tradition. We explored this phenomenon in our article with a critique of protestants and unionists who have engaged in Irish language learning projects.

A key aspect to our argument is the necessity for distinct types of dialogue in a post-agreement period, which are necessary in avoiding both the emergence of linguistic silos and the further problematising of language. We highlight the type of dialogue within the unionist community in relation to Irish as a form of positive intra-cultural dialogue. This dialogue within a seemingly monolithic community is significant as it occurs in safe spaces familiar to a particular ethnic group and provides the environment for difficult conversations to occur about the fluidity of cultural identity. Such conversations lay the foundation for later intercultural dialogue across communities. In this way we indicate that such work within a group is important in moving beyond singular interpretations of our identities, which are crucial to consider in any post-conflict context. Historically, there has been the lack of a formal, long-term structure at state-level to improve dialogue within and across communities on the language issue in Northern Ireland. Instead, the region has relied on local, parallel initiatives, which are highly dependent on audacious individuals and short-term funding. However, we argue for a more formal recognition of the need for dialogue within and between communities regarding language issues. These, we argue, require new organisational structures to succeed. The proposal from the Queen’s speech noted the establishment of two separate Commissioners in Northern Ireland - one for the Irish Language and a second for the Ulster-Scots tradition. Each commissioner will separately represent the interest of Irish and Ulster- Scots speakers. The precise nature of these two posts, we argue, requires much clarification. Their remit needs to be framed in a collaborative context if the necessary dialogue within and across communities is to emerge. The promise of a new office with two separate commissioners seems like a perfect moment to develop such a bridging structure between the two commissioners. This could formalise the role of dialogue in the implementation of language rights and subsequent language policy and in principals of collaboration between the work of the two commissioners. The potential of an office for cultural expression to foster intra and inter-cultural dialogues is huge, but it will require a bold and forward-looking strategy which recognises the malleable, fluid and changeable nature of identities in a post-conflict location like Northern Ireland.

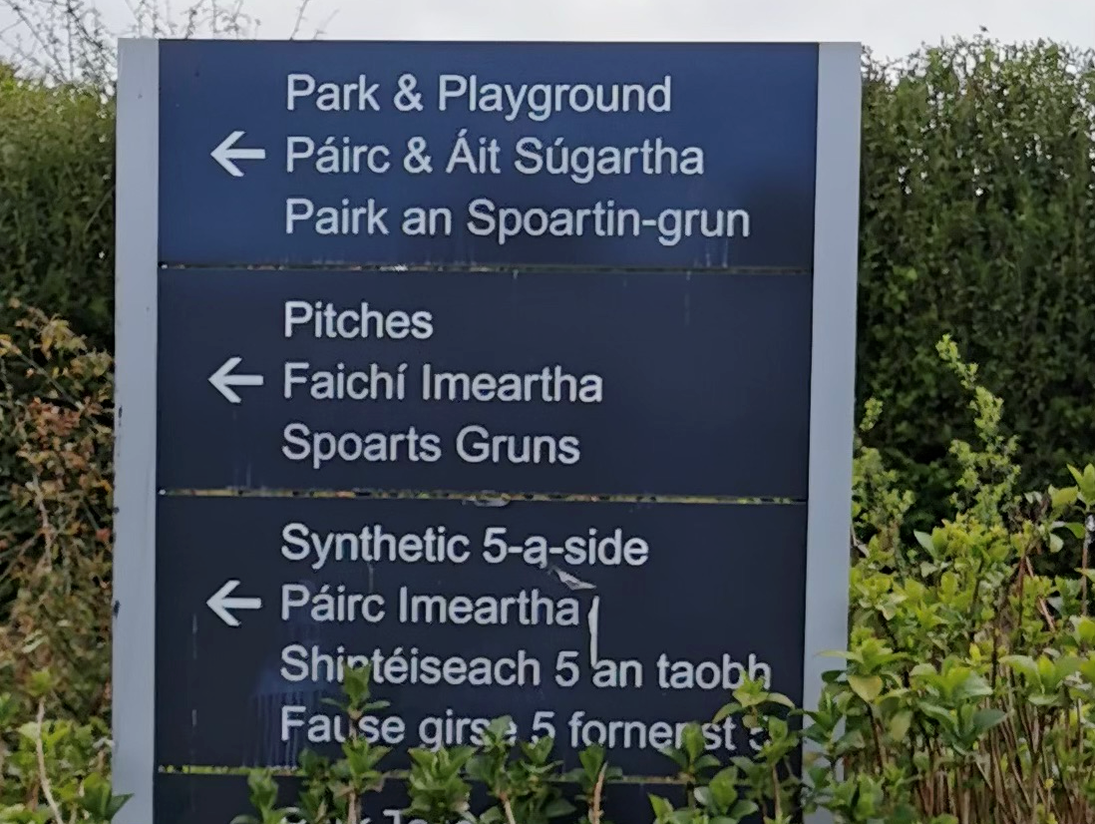

Image credit: Trilingual Signage in English, Irish and Ulster-Scots. Author's own, © P. McDermott

Blog post by Mairéad Nic Craith, University of the Highlands and Islands, Scotland and Philip McDermott, Ulster University, Northern Ireland

Read the Identities article: Craith, M.N. & McDermott, P. Intracultural dialogue as a precursor to cross-community initiatives: the Irish language among Protestants/unionists in Northern Ireland. Identities: Global Studies in Culture and Power. DOI: 10.1080/1070289X.2022.2063498 OPEN ACCESS

Explore other relevant Identities articles:

Ethnicizing Ulster’s Protestants?: Ulster-Scots education in Northern Ireland Whose ‘wee country’?: identity politics and sport in Northern Ireland What makes a Gael? Identity, language and ancestry in the Scottish Gàidhealtachd

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

|

Explore Identities at tandfonline.com/GIDE |

|

The views and opinions expressed on The Identities Blog are solely those of the original blog post authors, and not of the journal, Taylor & Francis Group or the University of Glasgow.