|

|

|

The concept of ‘cosmology’ has a long-standing history in anthropology. Derived from the ancient Greek ‘cosmos’ – order, harmony, world – and ‘logos’ – discourse – cosmology was historically intended as the knowledge or study of the structure and shape of the world.

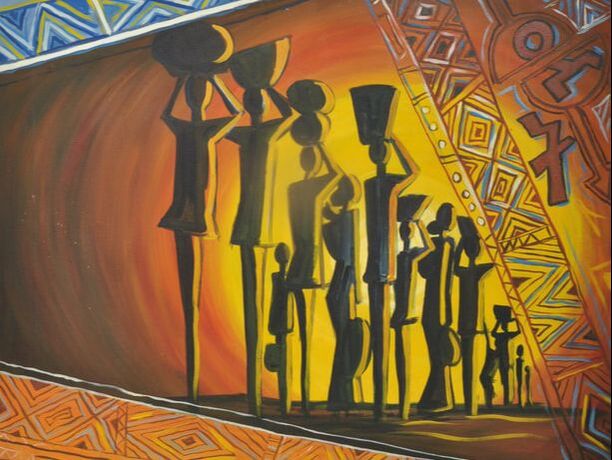

In anthropology, cosmologies are conventionally defined as widespread representations of the world as a hierarchically ordered whole. Traditionally associated with the study of religions, cosmologies have progressively come to refer more generally to systems of classifications, and their related moral and emotional attitudes. My Identities article, ‘Cosmologies and migration: on worldviews and their influence on mobility and immobility’, shows that this concept can be applied to understanding the hierarchical worldviews of a diasporic population, such as Eritrean migrants and their left behinds. In particular, the article argues that these worldviews are crucial to understand why people are ready to undertake very dangerous and complex journeys to reach their their 'promised land', as suggested by the Eritrean painter Ambasager Welday in his beautiful reinterpretation of the biblical exodus (see the image above).

To escape an undetermined national service, they leave Eritrea without a permit. They face the challenges of living as refugees in Ethiopia and Sudan with limited possibilities to move (out of camps) and prospects to work. Legal avenues to move out of these first asylum countries are also extremely limited: less than 1% of the refugee population worldwide manage to resettle in a third country. If Eritreans manage to reach southern Europe, usually Italy, they have a hard time finding decent housing and jobs that would allow them to achieve some socio-economic and existential stability. Due to the Dublin Regulation, however, many cannot easily move to other European countries. There are huge risks for those who attempt to cross the borders, including detention and harm, but being returned to Italy is often the most feared option among Eritreans.

The idea of cosmologies of destinations point to the specific moral prescriptions about where a migration journey should end and what the person that arrives there should do. The narratives of the many Eritrean refugees whom I met in Italy between 2008 and 2014 well represent these moral prescriptions. While survival in Eritrea becomes increasingly dependent on resources from abroad, Eritreans leave their homes not only to flee political oppression, but also to provide for those left behind. The journey, thus, should end where the migrant is able to fulfil his/her family obligations. ‘We are here for our families, not only for our own sake’, as one refugee living in a shanty town of Rome told me. He had already tried twice to seek asylum in Sweden and was on the verge of trying again. In this context of transnational obligations, moral worthiness is judged by families and local communities on the basis of the support that migrants are able to offer in many different aspects. The comparison between migrants settled in different countries reproduces not only a hierarchy of moral worthiness among migrants – it also shapes a hierarchical shared imaginary in which some countries are pictured as transit places, such as Italy, and others as desired destinations, such as northern European countries. Cosmologies of destinations represent crystallised hierarchies of geographic preferences widely shared by the members of a group. Building on previous literature on cultures of migration and geographic imaginaries, cosmologies of destinations point to the connection between imaginaries of places and the moral and symbolic values attached to living there. In doing so, it facilitates the understanding of how migrants can place their desired destinations in a hierarchy of value that motivates them to move on from the good to the better destination.

Blog post by Milena Belloni, The University of Antwerp, Belgium

Read the full article: Belloni, Milena. Cosmologies and migration: on worldviews and their influence on mobility and immobility. Identities: Global Studies in Culture and Power. DOI: 10.1080/1070289X.2020.1748357

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

|

Explore Identities at tandfonline.com/GIDE |

|

The views and opinions expressed on The Identities Blog are solely those of the original blog post authors, and not of the journal, Taylor & Francis Group or the University of Glasgow.