|

|

|

Blog post by Ioana Vrabiescu, Vrije University Amsterdam, Netherlands

In my Identities article, ‘Detention is morally exhausting’: melancholia of detention centres in France’, I invite the reader to reflect on two main issues: the perceived role of the law and the legal system and how these perceptions are translated into the organization of migration control. The perception of the law as fundamental to the state practices allows people to continue working alongside the migration control apparatus despite their beliefs that the law is not perfect. The tension in this context lies in the interplay between the perceived fundamental role of the law in the functioning of the state and individual beliefs about a deficient legal system. Despite these beliefs, individuals continue to work in the migration control apparatus based on their understanding of the law's fundamental importance. Within the migration control apparatus, I chose migrant detention centres as those sites that best reflect these ethical frictions, resulting in an atmosphere of melancholia.

0 Comments

Blog post by Katerina Rozakou, Panteion University of Social and Political Sciences, Greece

During my research in Greece, which forms the basis of my Identities article, ‘Ambivalent feelings: ‘filotimo’ in the Greek migration regime’, I explored ambivalent feelings that police officers demonstrate in their encounters with migrants in various sites of migration governance. Between autumn 2014 and summer 2016 I did fieldwork with state and non-state actors involved in migration in registration, pre-removal migrant detention, and open reception centres in Athens and Lesvos. Police officers in Greece are notorious for their anti-migrant and racist attitudes, and migration governance sites are infamous for their poor conditions as numerous reports by human rights organizations illustrate (Amnesty International 2014, European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment 2017, Greek Ombudsman 2019). At the same time, often police officers exhibit care towards migrants, providing them with medicine, food and other goods. This care is not a matter of individual exceptions in the dominant xenophobic police feelings but related to the culturally significant sentiment of ‘filotimo’ (love of honour) that police officers evoke. The ‘goodness’ and the acts of care that police officers exhibited towards migrants them as more than mere individual exceptions in an overall culture of neglect and dehumanization (though at times this may be the case). As I claim, this care very often coexisted with violence and xenophobia, and it resonated with nativist claims to morality and moral superiority that were contrasted to the demoralization of the state the police officers embodied.

Blog post by Bridget Anderson, University of Bristol, UK and Ioana Vrabiescu, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, Netherlands

The European Union presents itself as a global champion of human rights, yet its external borders are marked by hostility, surveillance and death. There is also an intricate network of borders within Europe that marginalizes and excludes migrants and asylum seekers. The vast majority of those excluded at the border and within Europe are people of colour. Two contemporary developments shape the context of our Identities Special Issue, Affective Control: The Emotional Life of (En)forcing Mobility Control in Europe – the global social movement for Black Lives and the COVID-19 pandemic. They have shaped conversations on structural racism and crisis-driven migration management and exposed the intersectionality of emotions and policies. For example, the invocation of national protection measures in the context of COVID-19 allowed European states to enforce border security under the guise of health protection, emphasizing the emerging pattern of governing migration through crisis management.

Blog post by Sebastien Bachelet, University of Manchester, UK and Mariangela Palladino, Keele University, UK

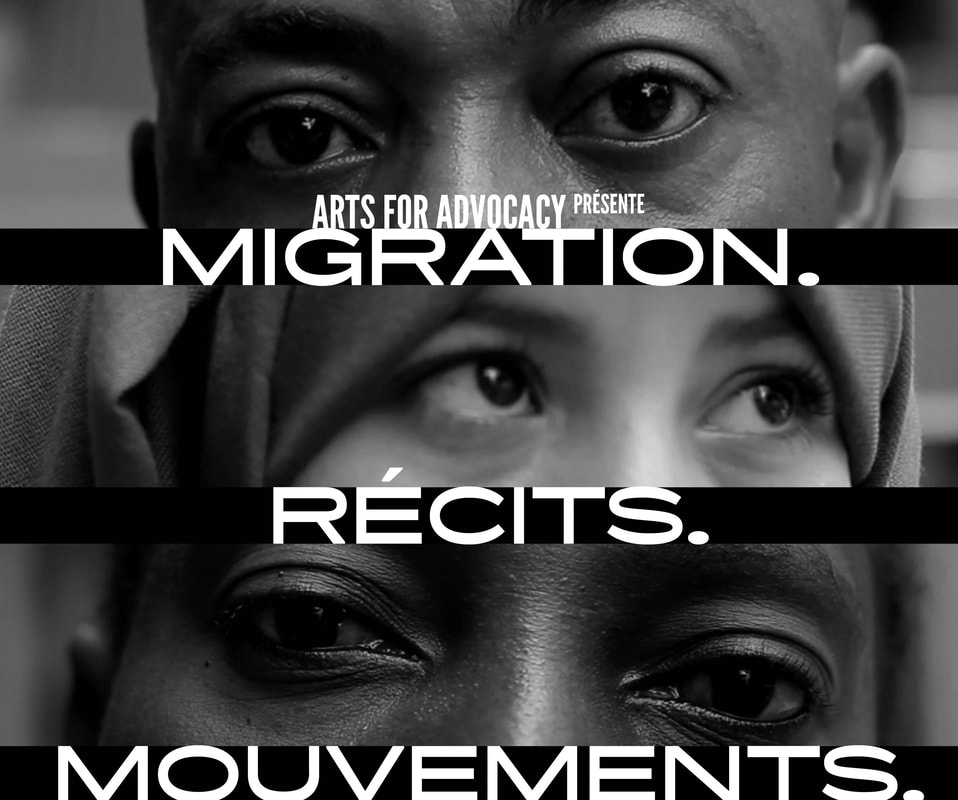

Overcrowded boats capsizing in the Mediterranean Sea feature regularly in the news. Yet, the discrepancy in the coverage and rescue efforts deployed for the boat carrying 750 people seeking safety which sank off the Greek coast, and the fate of the Titan submersible, is a stark reminder that vividly illustrates how some lives are more grievable than others. Talks of a migration ‘crisis’ moreover overlook the responsibilities and effects of European states’ hostile migration policies and violent bordering regimes. Public debates seldom scrutinize the political construction of migrants as illegal and undesirable, nor do they provide sufficient insights into people’s lives beyond abstract labels, especially south of the Mediterranean Sea, where European politicians propose to build asylum-processing centres. In this blog post, drawing on our Identities article, ‘Être vraiment vrai’: truth, in/visibility and migration in Morocco’, we focus on migration, creative processes and advocacy in Morocco, to demonstrate how narratives of migration that challenge expectations and demands for authentic and truthful migrants’ accounts can disrupt dominant and harmful forms of representation.

Blog post by Emiliana De Blasio, LUISS University, Italy, Marco Palillo, University of Bradford, UK and Donatella Selva, University of Florence, Italy

Over the last decade, the Mediterranean Sea has become one of the deadliest migration routes for asylum seekers and migrants wanting to reach Europe from Libya. In response to the high numbers of deaths associated with perilous journeys and dangerous smuggling strategies, numerous non-governmental organisations (NGOs) have been operating in the Mediterranean Sea to provide search and rescue (SAR) operations to migrant vessels in distress at sea. Over the years, the new centrality of NGOs’ humanitarian efforts in the Mediterranean Sea in the Italian public and media discourse has led to significant tensions with right-wing parties. Most notably, Matteo Salvini’s League and Giorgia Meloni’s Brothers of Italy have repeatedly criticised NGOs involved in SAR operations for facilitating irregular migration flows and defying Italian border control policies. Since its inauguration in October 2022, the newly installed government led by Giorgia Meloni has engaged in a series of clashes with NGOs running SAR operations in the Mediterranean Sea as part of the government’s hard-line stance on ‘illegal’ migration. In particular, Meloni’s government has promoted a new migration policy that introduces further restrictions on the capacity for NGO vessels to conduct multiple rescues in the same mission.

Blog post by Melanie Griffiths, University of Birmingham, UK

Political rhetoric around migration is often febrile. This has been especially evident in the UK in the last few years, with frequent talk of ‘crisis’ and ‘invasion’. Indeed, a government source in June 2023 described the small boats crossing the Channel as a ‘ticking time bomb’ threatening the UK’s social and economic security. Such discourse reflects an emotional turmoil of outrage and indignation, fear and panic, mistrust and repulsion. Alongside such splenetic rhetoric, however, the political response to irregular migration is also one of callous indifference and disregard. We see this lack of care demonstrated in the UK’s massive asylum backlog, with 170,000 asylum seekers now awaiting an initial decision. It is also reflected in the UK government’s plans to warehouse asylum seekers on boats and in military barracks, and to automatically banish new arrivals to Rwanda. These contradictory emotional displays act as a spectacle distracting from government failures to manage the immigration system effectively, but they have real-world impacts. This includes seriously and detrimentally affecting those navigating the immigration system, as well as wider societal impacts, with evidence of growing xenophobia and racially-motivated offences.

Blog post by Annavittoria Sarli, University of Birmingham, UK

Policy and media discourses in Italy refer to migration-related issues mostly in the language of emergencies, deviancy or alleged cultural threats. The everyday presence of ethnic minorities as a permanent constituent of society is rarely acknowledged. Such public discourse perpetuates a kind of socio-cultural immaturity, making it difficult for the population to accept growing diversity. ‘Italianness’, moreover, tends to be conceived as monoracial and monocultural. This idea of national identity drives an imagined net division between a monolithic national ‘us’ and ‘the others’ foreigners, who comprise both first generation migrants and their Italy-born descendants. It is an imaginary enshrined in the Italian law on citizenship, introduced in 1992 and never updated since then. Mainly based on jus sanguinis, it poses obstacles for migrant immediate decedents (MIDs) to become citizens of the country where they spent most of their lives.

Blog post by Hamdullah Baycar, University of Exeter, UK

‘It kind of makes me feel like Batman or Superman. You can say the things you want to say with your own voice and your own style’, said Malcolm Bidali, a Kenyan security guard employed in Qatar, regarding his activism about labour conditions on social media. His activism led to his detention in 2021. The incident gained significant public attention, and 240 Qatar Foundation students, alums, faculty and staff signed a petition asking for his release.

Two days after the petition, even Qatar's state-owned media, Al Jazeera, was involved in the debate and ran with the headline, ‘Concerns over Qatar's arrest of a Kenyan security guard’. Thus, the digital sphere, which initially caused his detention, ultimately became the tool that freed him. Although Bidali's case cannot be considered representative of the entire Gulf region and is not directly related to the UAE, it does demonstrate the power of social media and the digital sphere, even in supposedly autocratic states.

Blog post by William Shankley, University of Nottingham, UK

Nearly twenty years have passed since the expansion of the European Union (EU) led to the significant movement of Polish citizens to the UK. Despite the UK's subsequent departure from the EU, Polish migration assumes a prominent place in the country's migrant diversity. Belonging is a crucial aspect of migrants' lived experience in another country, and previous studies on Polish migrant belonging in the UK have primarily focused on the neighbourhood context as this is contested, resisted and reshaped. Additionally, the majority of existing research has predominantly concentrated on Polish migrants' belonging among those working in low-skilled industries, which was the dominant occupational position most Polish migrants entered into. Nonetheless, Polish migrants' entry into a range of workplaces after their migration offers an equally important site in which to examine their belonging. Furthermore, there has also been a lack of research into Polish migrants working in professional occupations and their belonging at work.

As a team of international scholars with Czech and US origins living in Czechia and Austria, the 2015 ‘refugee crisis’ hit us in contrasting ways with regard to different regimes and their attitudes towards refugees from Syria and other Middle Eastern countries. While Czechia accepted just twelve refugees under the EU’s quota system, the Austrian public broadcasting station FM4 changed its jingle from ‘You're at home, baby’ to ‘Refugees, welcome’.

Seven years later, as we finalized work on our Identities article, ‘I always felt I have something I must do in my life’: meaning making in the political lives of refugee non-citizens’, the situation had somewhat reversed. In the spring of 2022, the streets of Prague were filled with Ukrainian flags, Czechia had accepted over 300,000 refugees in just a few months, and people became emotional regarding the war, while Austria, as a ‘neutral’ country and a non-member of NATO, was considerably more reserved.

The arrival of large numbers of Ukranian refugees fleeing the Russian invasion to their country since February 2022 has been met with a wave of compassion and solidarity in most western European countries. However, critical voices have pointed out what has been perceived as hypocrisy, or a ‘double standard’, regarding attitudes towards refugees. Why are some of them welcomed with open arms, while others are being repressed at the border? While Ukrainians could fast-track their asylum claims and enjoy protection status with minimum requirements, people fleeing other conflicts in the Middle East and Africa were still getting stuck in lengthy bureaucratic processes and often becoming the object of resentment and discrimination in the host society. Is this so because of racial difference?

The increased arrivals of refugees in a short span of time reminded many in Europe of the peak of arrivals from Afghanistan and Syria in the mid-2010s. Public opinion in various western European societies of alleged unbridgeable cultural differences or difficulties towards ‘integration’ of the newly arrived did not apply to Ukrainian refugees. While Ukrainians, critical voices argued, were perceived in the mainstream public opinion as ethnically, culturally and racially close to western Europeans, other victims of armed conflict equally entitled to protection were still represented or perceived as ‘less deserving’ by social and political actors holding anti-immigration positions. This shows the extent to which the way migrants are portrayed in Europe is a highly contested matter that connects deeply to values, perceptions and anxieties permeating those societies.

Earlier this year, Home Secretary Suella Braverman announced she was not proceeding with multiple recommendations made by Wendy Williams’ public inquiry into the Windrush Scandal. The inquiry examined the Home Office’s adverse actions against people from the Windrush generation who predominantly migrated to Britain from the Caribbean between 1948 and 1973 (Gentleman 2019; Slaven 2022). Reports have detailed the profound effects on those directly impacted, revealing stories of individuals who were denied healthcare and welfare services, and in some cases were ripped away from their families; detained and even deported (Gentleman 2019; Williams 2020; Slaven 2022). The ensuing scandal thrust their treatment into the public consciousness and ignited a public uproar. Yet, as the scandal faded from media attention, we still have a limited understanding of the scandal’s broader impact on Britain's racialised communities, beyond those directly affected by the Home Office’s actions.

One glimpse at minority language protection: the fine line between empowering and segregating24/5/2023

On 5 November 2022, the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages celebrated its 30th anniversary. This charter lays down the principles for protection and promotion of minority languages and their use in education, cultural life, public services, and other sectors within the EU. Undoubtedly, such supra-national and similar national policies generally improve the rights and lives of minority members.

My Identities article, ‘Drifting borders, anchored community: re-reading narratives in the semiotic landscape with ethnic Lithuanians living at the Polish borderland’, discusses a concrete example of one such minority protected on national and supra-national levels – the national Lithuanian minority in Poland. I provide a glimpse into the realities of its members’ language use, identification and narratives of belonging. I learned that they find some official minority protection attempts more concerning than helpful.

During the 2019 debates around the introduction of the EU Settled Status (EUSS), which regulates the rights of EU citizens in the UK after Brexit, Labour MP Yvette Cooper described the scheme as a potential ‘Windrush on steroids’. The reference was to the ‘Windrush generation’ scandal, in which Commonwealth citizens, who arrived in the UK with a permanent right to stay, were classified as unauthorised migrants, deprived of the right to work, rent or access welfare, and in some cases deported. The Windrush generation scandal has focused on people who arrived from the Caribbean, and the publicly known cases and data on compensation applications show that Jamaica has been the single most common country of origin. However, it is not possible to determine precisely the extension and geographical profile of the scandal, also because of the initial refusal of the Home Office to review historical cases beyond the Caribbean to identify potential unjust treatments.

The Windrush generation scandal is mainly the result of the ‘Hostile Environment’ policy, which extends and multiplies controls of migratory status. As the Hostile Environment encourages targeting racialised groups, it can be seen as a continuation of the racism to which the Windrush generation has been subject since their arrival in the UK. The ambiguous status of those Commonwealth citizens – who arrived with British passports but less rights than the British-born, and the limited documentation of their status, made them further vulnerable to the injustices they underwent. The argument of the critics of the EUSS is that, as the status does not come with a physical document, and is digital-only, this endangers EU citizens in the UK to be in the future miscategorised and mistreated as happened with the Windrush generation. In my recent article for Identities, ‘The vulnerability of in-between statuses: ID and migration controls in the cases of the Windrush generation scandal and Brexit’, I use several documentary sources and interviews with EU citizens in the UK and British citizens in Belgium to explore the degree to which Brexit and the Windrush generation scandal pose similar questions in terms of ID and legal status. From the institutions to the streets: the role of emotions in Barcelona’s migration control8/3/2023

In her essay The Cultural Politics of Emotions, Sara Ahmed raises the question: ‘What do emotions do?’, implying the social circulation of emotions. Even if felt by each individual in a unique way, emotions are addressed collectively, creating affective connections which in turn craft social realities.

There is a diverse range of institutions and practices that make up migration control in Barcelona. Despite the claim that it is governed by the rule of law, where there is no room for subjective or accidental decisions, emotions play a key role. What do a practitioner employed by a municipal institution in charge of migrant inclusion and a person categorized as a migrant with precarious legal status share, when they meet face to face? They do not know each other and they have never met before, but a bond is assumed to be created between them. They find themselves in an unequal power relationship, since the institutional practitioner has the power to decide through their intervention on the fate of their interlocutor. What is left in this connection which is not direct or spontaneous, but rather mediated by protocols and paperwork, and in which each person already has an assigned role which he/she plays or contests? I tried to answer these questions in my Identities article, ‘Back in order’: the role of gatekeepers in erecting internal borders in Barcelona’, exposing the role of emotions in migrants’ control in urban space, what I understood as a bordering practice.

As a scholar of migration who had spent several years doing research in Berlin, I have always been interested in the question of displacement in West Africa. I had met many migrants who had arrived from West African countries such as the Gambia, Senegal and Guinea-Bissau in Berlin. It is a well-known fact that significant numbers of people risk perilous journeys to reach Europe. Hence, in collaboration with two researchers I decided to conduct a study in Senegal in order to find out how, why and to what extent small-scale fishers become displaced. Prior to undertaking the research, I had visited Senegal for a holiday and had acquired a fair idea of some of the socio-political issues in the country.

We were fortunate enough to receive some small-scale funding from centres such as MIDEX and C4Globe. We were also fortunate to connect with an interpreter/research assistant in Senegal who spoke English, French and Wolof and assisted us with methodological approaches, conducting interviews and with transcription. He had friends and family in all three of the villages where we did our research, and we had several follow-up questions even after the interviews were conducted. As researchers from the Global North we were aware of our privileged positions, but at the same time the two European-based researchers originated from Nigeria and Pakistan which had a bearing on some of the power dynamics.

In our Identities article, ‘I became a Taiwanese after I left Taiwan’: identity shift among young immigrants in the United States’, we seek to engage with transnationalism literature, which argues that migrants continue to remain concerned with their origin country. As our case study shows, successful assimilation into the host country does not mean migrants will relinquish their previous attachment. In fact, fresh experiences abroad might actually activate and intensify their homeland identity. Our study documents unpleasant contacts with people coming from People’s Republic of China (PRC) and personal experiences with the immigration rules that favour Taiwanese. Our interviewees also share the disenchanting discovery that America was actually lagging behind Taiwan in terms of healthcare, public transportation and recycling, which encourages these young migrants to cherish heir Taiwanese identity. In short, being Taiwanese is something one can take pride of, and therefore, our interviewees explained they do not want to be viewed by people from PRC as their 'compatriots’ or identified as ‘Chinese’ by their American friends.

After China turned into a popular migrant destination, foreign-Chinese couples became a common sight on the streets of Chinese cities. In my early years of living in China, as a language student in Beijing (2005-2009), I already developed an interest in the romantic relationships I would later study as an anthropologist. My circle of friends included many Chinese-foreign couples, and our love lives were a favourite topic of conversation. These conversations were often marked by circulating beliefs about dating in Beijing for foreigners, such as the idea that Chinese women liked white men, but white women did not like Chinese men. This idea was both widely shared and regularly challenged by couples who proved the opposite. We also debated the contentious position of the white man in the Beijing dating scene. Was he wildly popular for being perceived as rich, handsome and worldly by Chinese women? Or was he regarded with suspicion for possibly being a player or a benguo luse (本国卢瑟)? This term translates to ‘loser back home’ and is popularly used to undermine the admiration that is perceived as being extended to white men too easily.

Migration enforcement is accompanied by emotions expressed by various actors – including the broader public, politicians and those targeted by practices such as deportation and detention – but also those of bureaucrats who implement policies. Emotions are addressed towards or expressed against a multitude of groups, such as asylum seekers or migrants with precarious legal status, as well as police officers and administrative and non-governmental staff.

Studying emotions directed at different groups uncovers, on the one hand, the intricate and complex network of actors working within the field of migration enforcement, both new and old. On the other hand, it presents the researcher with a density of relations that, as I argue in my Identities article, ‘Tracing the circularity of emotions in Swiss migration enforcement: organizational dissonances, emotional contradictions and frictions’, can be analyzed through a focus on emotions, thus advancing our understanding of statecraft and organizational construction.

Gender, as expressed on namely the bodies of Muslim women, is positioned at the centre of the radical right’s linkage between migration and religion. This link is visible in the persistent debates on the ban of Muslim body-covering, which in Austria has been promoted by the Austrian Freedom Party (FPÖ) since the turn of the century.

FPÖ’s debates on the ban of Muslim body-covering – of the headscarf in kindergartens and schools or of full body-covering in public spaces – which re-emerged since 2015, illustrate that the radical right instrumentalizes the intersection of gender, body and religion in its search for new forms of governing. As I explore in my recently published Identities article, ‘Radical right populist debates on female Muslim body-coverings in Austria. Between biopolitics and necropolitics’, the radical right’s debates over female Muslim body-covering are embedded in the neoliberal reorganisation of societies and a crisis of governability, which radical right-wing actors use to implement their own biopolitical and necropolitical projects.

The COVID-19 pandemic profoundly transformed people’s lives, identities and practices throughout the world. It had particular effects on the group of international students who usually move frequently between home country and study destination. When the pandemic hit their study destinations in 2020, they had to take immediate action and plan migratory trajectories accordingly.

Chinese international students (CIS) also experienced a nationwide pandemic control policy at home that caused continuous travel constraints on international flights and passengers landing in China. The domestic policy had a profound impact on their migration aspirations – to remain in the study destination or to return home. Simultaneously, students reconfigured their perceptions of homeland. Our research, as detailed in our Identities article, ‘Migration aspirations and polymorphic identifications of the homeland: (Im)mobility trajectories amongst Chinese international students amidst COVID-19’, includes semi-structured interviews with 33 CIS studying in 23 cities of 10 European countries (including the United Kingdom). We aim to understand how students’ identifications of homeland – a cognitive assemblage of emotions, commitments and reflections towards their home country – intersect with their migration aspirations.

Romania has several multicultural regions, including the Banat in the southwest. During its time as part of the Habsburg and Austro-Hungarian Empires (1718-1918), cultural influences and economic developments from the West (German, Austrian, and Hungarian) made it an attractive destination for migrants. This continued after the Trianon Treaty and Romanian unification in 1918, as Banat was economically advanced compared to other regions to the East and South. Rapid industrialization and urbanization under the communist regime (1947-1989) and the subsequent removal of restrictions on movement in the early post-communist period also saw steady internal migration patterns.

Despite this long history as a recipient of migrants and cultures, the sense of nativism and place belonging is strong among Banateni. Proximity to Central Europe also led to a sense of discrimination, as Both noted, a Banat resident ‘would better prefer a German, Serbian or Hungarian than a migrant non-Banat Romanian’ in their village. In our recent Identities article, ‘Internal migration and stigmatization in the rural Banat region of Romania’, we attempted to uncover attitudes towards internal migrants and how these were understood by migrants themselves in rural Banat.

We recently published our research about a potential rise of anti-Scottishness in England, post-Brexit, in Identities. This wasn’t originally the article we intended to write. We actually started off by exploring Scotland’s population challenges – a negative rate of natural change, an ageing population and population growth reliant on inward migration – issues which other Western countries are wrestling with. For Scotland, there is the added complication that the country has no control over migration as this is reserved to Westminster, and the present Conservative government is, in any case, committed to reducing the numbers coming to the UK.

So how did we come to write ‘Indifference or hostility? Anti-Scottishness in a post-Brexit England’? In the best academic traditions, we had begun by undertaking research with returning members of the Scottish diaspora – individuals who may have been born and educated in Scotland but who had been living and working elsewhere. Some had begun to move back to Scotland, suggesting that, for these individuals and families at any rate, their economic or personal circumstances were encouraging a homeward move.

Avery Gordon identified a problem with sociology over two decades ago when they wrote Ghostly Matters: Haunting and the Sociological Imagination. Despite the sociological aim of unlocking knowledge about social life, the emphasis on empiricism left what remains absent outside its purview. According to Gordon, haunting is the means of understanding how what remains absent within social life attempts to make itself known.

Such a methodology is important when understanding contemporary queer migration. Whether queer migrants need to keep in the shadows because they fear they might be deported by the state, or whether they remain in the closet because they fear they will not be accepted due to their sexuality and gender, there is much to be learnt about what remains absent within narratives on queer migration. Although sociolegal analysis has done well attempting to uncover more about queer migration and the lives of queer migrants, particularly as related to those claiming asylum, it must be recognised there are limits on what can be learnt. There will always be experiences that fail to make the headlines of media outlets or the reports by nongovernmental organisations, which prompt two possible responses. On the one hand, one may seek to know more using the established methodologies of sociology. On the other hand, one may seek to grapple with what remains absent but becomes haunting.

What happens if young migrants are deprived of maintaining contacts to close friends and relatives over a very long period of time and across different countries? What impact does this have on their personal development and their outlook on life?

In my Identities article, ‘Transnational social fields in forced immobility: relations of young Sub-Saharan African migrants in Morocco with their families and friends’, I attempt to find answers to these questions by focusing on young African migrants in Morocco. The young people that I interviewed had travelled without any family members or friends when they left their origin countries. All of them had to use a variety of legal and irregular means to cross borders during their journey through different countries. Most of them had been travelling months and sometimes years before arriving in Morocco. By the time they got there, they had used most of their financial resources and often had lost contact to their social networks. Because of their irregular status in Morocco, they could neither move back south nor travel further north towards Europe. Underemployment and poverty limited their access to social media and modern technologies, so that their ability to communicate with their relatives and friends became sporadic. |

|

Explore Identities at tandfonline.com/GIDE |

|

The views and opinions expressed on The Identities Blog are solely those of the original blog post authors, and not of the journal, Taylor & Francis Group or the University of Glasgow.