|

|

|

On 25 February 2020, the Danish newspaper Berlingske had a main story showing how leading party members of the Social Democrats have put pressure on experts critical of the Party’s politics. Both while being in opposition and now forming the minority government, leading politicians have contacted organisations and independent experts (Holst 2020). The newspaper reports how experts and researchers have been contacted by people working for the Social Democrats or from people within the ministries and given warnings. The issues at stake do not all relate to migration research, but some do.

The story therefore connects well to my analysis presented in my Identities article, 'What makes an expert? Doing migration research in Denmark'. In the article, I outline four different types of migration experts who in different ways and with different weight have to navigate within a nexus of academia, the policy arena and the broader public. The first of these types is a positioning of the migration expert as one not offering any real solutions. This discussion stems from an internal debate within academia where a well-esteemed professor argued that a large part of research is becoming decoupled from ‘real politics’ and ‘reality’. The implication for him is a situation where the research community has created a ‘vacuum’, and in the absence of asylum and refugee researchers who can assist the decision-makers the politicians have begun to look for advice elsewhere.

0 Comments

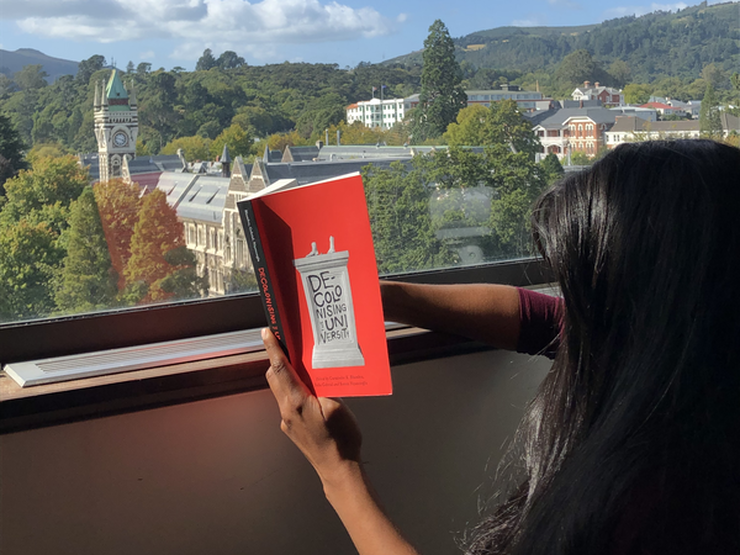

Recent calls to decolonise the university in South Africa culminated in the removal of the statue of Cecil John Rhodes at the University of Cape Town and breathed new life into student-led campaigns around the world to rethink the curriculum. Challenging the colonial roots and Western biases of universities is, of course, not a twenty-first century phenomenon. However, in its latest iteration, the need to decolonise the university has been more clearly connected to the lived reality of the corporatised university as a distinct feature of the neoliberal era. Bringing debates on neoliberalism into closer conversation with a consideration of how neocolonialism is expressed in institutions of higher education has allowed for closer scrutiny of what ‘transformation’ actually means.

It has become abundantly clear to many of those who work and study in higher education, that the more things change, the more they stay the same. While the language of transformation has been woven into policies that have widened access to previously marginalised groups (including black and minority ethnic groups, women, indigenous and mature students), institutions of higher learning have a long way to go to dismantle the barriers to success that these groups face once inside the institutions.

The Domari Gypsy community of Jerusalem is relatively small; estimates suggest it comprises around 111 families. The numbers are larger in Gaza and the West bank, where it is estimated there are 15,000. Many Palestinians and Israelis are not aware that this community lives at the heart of city.

In the Arab world, and East Jerusalem included, Domari people are referred to as 'Nawar', a term which is said to be derived from fire. The Tribal Leader of the Domari in Jerusalem says that the word 'Nawar' (related to Noor or ‘light’ in Arabic) was given to them because they came to Jerusalem with the Muslim fighter Noor Al Din Zenki who fought alongside Salah Al-Din in 1187. Another suggested reason for the name is that many of the Domari worked as blacksmiths who used fire. However, stigma and discrimination against the community has led the name 'Nawar' to be filled with negative connotations; the word has evolved to describe unruly behaviour, as an insult, and is very much in use in conversation today. I started researching the Domari community in Jerusalem in 2017. Getting members of the community to engage in this research was not easy. Palestinians residing in occupied East Jerusalem, including the Domari community, are in constant fear and suspicion of people asking questions about their lives, due to the fact that they do not have settled citizenship status in Israel and they only have residency permits. Following the occupation of East Jerusalem, Israel granted the Palestinian community and the Domari community living there residency status. With no citizenship status in any other country, their fragile legal status makes them reluctant to share information about their lives, as they fear they risk losing their residency rights.

On 26 February 1920, the 276-page Darkwater: Voices from Within the Veil – written by renowned sociologist W. E. B. Du Bois – appeared in bound print. Published at the zenith of Jim Crow, the book contained autobiography, cultural criticism, poetry and sociology. These were marshalled, in Du Bois’s words, to 'strike here and there a half-tone . . . up from the heart of my problem and the problems of my people' (1999 [1920]:ix).

People took notice. The reading public drank deeply from Darkwater: the first run of 5,000 copies soon sold out, followed by a second run selling out and a third run of 5,000 produced and sold by July 1921. Critics too, waded into Darkwater, resulting in many a published response. In reviewing Darkwater, the 29 April 1920 edition of the Daily News called Du Bois a 'raving madman' and his book a 'hymn of hate' before cautioning that 'it should be read by those whites who are able to restrain their tempers under an attack, not merely venomous, but lacking the faintest regard for either justice or truth' (4). In a decidedly dissimilar tone, the 28 July 1920 edition of the Cleveland Plain Dealer printed a review describing Du Bois’s text as '. . . an appealing and touching work, marked both by pathos and by power' (Rose 1920:8). |

|

Explore Identities at tandfonline.com/GIDE |

|

The views and opinions expressed on The Identities Blog are solely those of the original blog post authors, and not of the journal, Taylor & Francis Group or the University of Glasgow.