Feeling of desperation is doubled due to COVID-19 among undocumented African migrants in Istanbul27/4/2020

Dogus Simsek, University College London, School of Slavonic and East European Studies, UK

A few days ago, I received a WhatsApp message from an undocumented migrant living in Istanbul stating that, 'Our situation is getting worse. I lost my job because of coronavirus. I am stuck here with my child. I do not know how I will pay the rent, buy food for my child. I do not know what to do if we catch the virus. We cannot go to hospital. We are stuck here with very limited facilities. I am very worried about our lives. There is no one to help us. Many of us who do not have documents feel very desperate at the moment'. This is probably one of the worst experiences she has gone through since she migrated to Turkey from Ghana. Trying to understand this feeling of desperation without the social, political and cultural context is hard.

While the exact number of African migrants living in Turkey remains unknown, a period of migration in the 2000s leaves us with estimates between 500,000 to 1 million — of which between 50,000 and 200,000 are said to live in Istanbul. The majority of African migrants in Istanbul hail from Sub-Saharan Africa, West Africa (Nigeria, Mauritania, Senegal, Ghana), Central Africa (Democratic Republic of Congo), East Africa (Somalia, Ethiopia, Eritrea, Rwanda) and North Africa (Morocco, Tunisia, Algeria and Libya). Most of the African migrants entered Turkey with a tourist visa and did not renew it, thus becoming 'undocumented migrants'. The majority of those I met during my fieldwork in Istanbul explained that they viewed Turkey as a transit country from which to go to Europe. Yet, given the dangerous and costly nature of these travels, they were forced to remain in Turkey for many years and had spent most of their savings during their migration journeys.

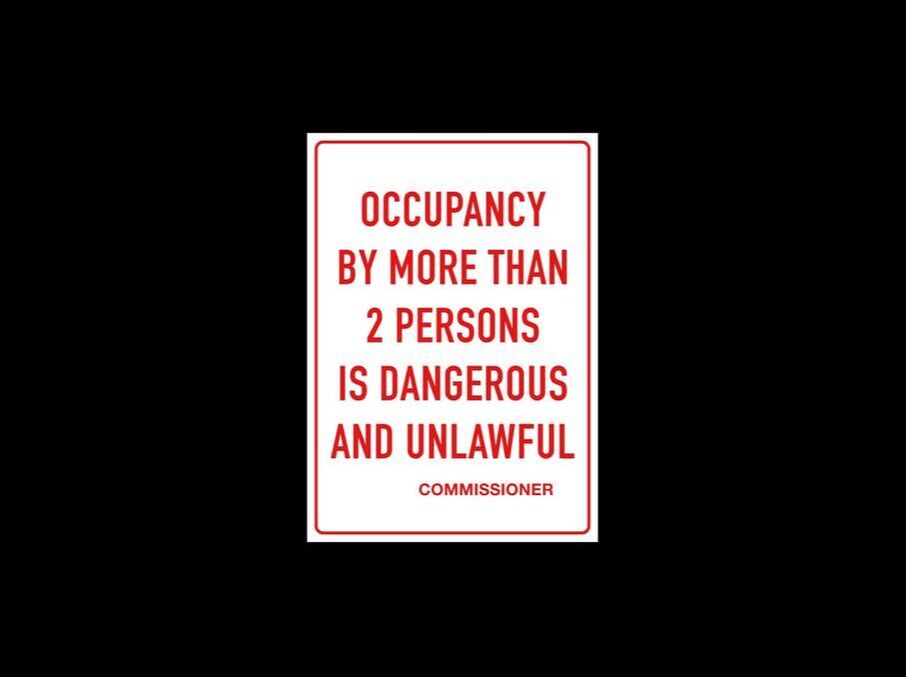

Under 'normal' circumstances African migrants living in Istanbul are, on the one hand, striving to hold onto life and integrate into the society to which they migrated; while on the other hand they are being forced to confront discrimination, alienation and racism on a daily basis. Indeed, undocumented migrants in Turkey regularly face many barriers such as being forced to work in the informal economy, living in a hostile environment riddled with everyday racism, not being entitled to healthcare including mental health services, lacking mobility, and most importantly, living in fear of being deported. Not only do these barriers hold undocumented migrants back from the early stages of migration, but the spread of COVID-19 can be expected to exacerbate their vulnerability for a variety of reasons. Undocumented migrants are more vulnerable than other groups because they are more likely to find themselves in overcrowded working environments, living with many people in small flats, have precarious job security, and lack access to healthcare. These living conditions are less than ideal on their own, however, during a health crisis like the one we find ourselves in, these existing conditions are incompatible with many public health precautious that are being instituted. Take social isolation for example. Poverty drives many undocumented migrants in Turkey to live in the margins of society in low-income housing often with large families in a single apartment where social isolation is impossible. Their working conditions also do not allow them to socially isolate as most of them work in large warehouses and textile workshops with many other employees. Additionally, undocumented migrants in Turkey do not have access to health care which makes them even more vulnerable to infectious disease because they may not be able to go to hospital if they are infected. Lastly, language barriers pose significant challenges to their ability to access accurate public health information as few sources have been translated into French or English. The confounding effect of these circumstances means that the COVID-19 outbreak is making life more unstable and uncertain for many undocumented migrants leaving many of them feeling more desperate than before. Since the COVID-19 outbreak began, African migrants I have been in touch with have stated that they are experiencing racism on the street and institutionally more than before. A young African migrant from Ghana confided that, 'Turkish people treat us even worse than before because they believe that we (Africans) carry the virus. I am scared to walk on the street because of racism'. Prior to the COVID-19 outbreak, nearly every African migrant I talked to in restaurants, cargo companies, and hair salons in Kumkapı during my fieldwork stated that the discrimination and racism they were exposed to had become a normal feature of their daily lives. Because of this, they did not feel safe or secure and walking outside during the night was dangerous for them, especially in Kumkapı because they were often subjected to robberies and racist attacks in this area. As a result, they feel safer when they are together in their own social spaces and specifically remarked that they felt safer when keeping a distance — a strategy they developed in order to protect themselves. The picture of a murdered African friend hangs in the window of a Nigerian restaurant I visited in Kumkapı — a situation that clearly demonstrates how they experience the concept of solidarity privately between themselves. African migrants I contacted are also worried that losing their jobs due to the spread of coronavirus will force them to live in extreme poverty. The majority of African migrants work as laborers in textile workshops and when prompted detailed a lack of security, difficult working conditions, long hours, and little pay—conditions that can be expected to worsen if the workshops are forced to close in response to COVID-19. Furthermore, women experience an additional layer of exploitation in the workplace through sexual harassment. Some of the women I interviewed during my fieldwork detailed being sexually harassed by their employers and stated that they were threatened with losing their jobs if they did not reciprocate their advances — many of whom lost their jobs for this reason. Indeed, a Ugandan woman working in a textile workshop described the difficult working conditions for African women by stating that, 'There is the impression that all black women in Turkey are sex workers. For this reason, the majority of African women experience sexual harassment at the workplace and on the street. The majority of employers at textile workshops attempt to rape their African female workers and threaten to fire them if they reject the sexual advances'. Unfortunately, she is not alone as I heard this from a lot of African women who explained that being a woman, in addition to being a migrant, brought with it an abundance of troubles as they were trying to carry on through existing uncertainty and poverty. Racism and workplace struggles aside, not having access to health care is perilous, and it is in the best interest of governing officials to see that in this time of COVID-19 their health is tightly linked to the wellbeing of society as a whole. Dogus SimsekDr Dogus Simsek is a Teaching Fellow in Political Sociology at the UCL School of Slavonic and East European Studies. Her research interests broadly cover forced migration, race and racism, gender and migration and second generation and identity.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Identities COVID-19 Blog SeriesExplore expert commentaries curated by Identities surrounding COVID-19 and displaced migration, nationhood and citizenship, and more. Blog Categories

All

|

Explore Identities at tandfonline.com/GIDE |

|