On racism, inequalities and the emergence of vaccine apartheid: notes of a vaccine trial volunteer7/5/2021

At the time of writing this piece, I was confronted with two strikingly different scenarios. One, involved friends in the UK posting images of their vaccine cards on social media (and I am proud of them for taking the first step in making themselves and the world a safer place). The other, involved friends and relatives in India calling out for emergency oxygen cylinders and empty ones, telling stories of lifesaving medication sold on the underground market at 200% markup and lengthy queues outside the hospitals. Some friends in India have also been paying respects to and memorialising people they know who have died. Social media feeds are filled with pictures of bodies lying in queue to be cremated, and makeshift funeral pyres built in parks and parking lots as city crematoriums have run out of space. The official statistics, which are already scary, understate the rise in cases and deaths, and these images often show the true scale of suffering.

In addition to the two different pandemic related scenarios mentioned at the beginning, I also live in two different realities and have two very different experiences simultaneously. I am from India. I live in the UK and have citizenship of the country. I am an academic who works on racism and migration. Last year, I was a vaccine trial volunteer and have now been vaccinated, while my mother and brother live in the outskirts of Mumbai and both contracted COVID-19 in early April. They are recovering, but both continue to cough and feel weak. Their oxygen levels are in the healthy mid-upper 90% range, so neither need oxygen or hospitalisation. Both need a lung CT scan, but they are avoiding hospital visits as it is overflowing with patients who need urgent intervention, and they also fear getting re-infected. A few other relatives are hospitalised or using oxygen at home. As you can imagine, the past few weeks have been filled with worry, dread and sadness. Living 4500 miles away and not able to physically be there and help also continues to cause me a great deal of frustration and guilt. I am facing another layer of diaspora blues, from Ijeoma’s book of poetries.

0 Comments

COVID-19 shines spotlight on need for strengthened mental health response for asylum seekers28/9/2020

Caitlin Katsiaficas, George Washington University, USA

Many of us have been spending much more time at home, separated from friends and family members, to help curb the spread of the coronavirus pandemic. Movement restrictions and social isolation, along with fear and uncertainty about the future – perhaps coupled with financial stress – can all have important consequences for our mental health. This has led the World Health Organization (WHO) to call for an injection of funding for mental health services as part of the global COVID-19 response and recovery, while among the general public, the topic of mental health and wellbeing has received more attention. But although the pandemic has cast light on these challenges, they are nothing new for many migrants.

Mrunmayee Satam, Amity Institute of Liberal Arts, Amity University, India

Chinmay Tumbe, author of India Moving: A History of Migration, once articulated in an interview that – ‘while the city offers economic security to the poor migrant, their social security lies in their villages, where they have assured food and accommodation’. It has been said that the economic sector is the first to receive a setback during an outbreak of any disease. It is no surprise, therefore, that historians of the social history of health and healthcare have highlighted that epidemics and pandemics trigger the process of reverse migration — a phenomenon wherein people will travel in the opposite direction of what they would typically follow. This means that when there is a great deal of uncertainty surrounding their daily wages, migrant populations residing in cities prefer to travel back to their home towns in the countryside in search of social security.

The ‘Othering’ of returnee migrants in Bangladesh as they are seen as COVID-19 ‘importers’22/6/2020

Ala Uddin, University of Chittagong, Bangladesh

While many countries were taking necessary measures to fight the coronavirus, Bangladeshi leaders were largely in denial of the magnitude of the pandemic and were busy making speeches in line with this tune until around mid-March 2020. As we watched the virus spread across China, Europe and America, we were continuously reassured that, like other flus (e.g. Swine flu, SARS, Ebola or Zika), coronavirus would not hit Bangladesh. Despite these delusions, the first COVID-19 patient was eventually confirmed on 8 March 2020, with the first death following only ten days later. Time and again, we were assured that 'we are prepared enough to fight against the virus', and that it is 'like flu, not serious diseases'. However, even as COVID-19 was being brushed off, weariness and mistrust was already building against migrant workers, foreign travelers and other outsiders as they were quickly blamed for bringing COVID-19 into Bangladesh — an attribution that has resulted in both internal and returning migrants experiencing ‘Otherness’ in their own society.

Mehr Mumtaz, Ohio State University, USA

COVID-19 has not affected all communities equally, and within the United States, racial and ethnic minority groups have been disproportionately affected by the virus. Reports indicate that immigrants and refugees, who constitute a large portion of the minority frontline workforce in healthcare, agriculture, and food supply chain industry, are at a higher risk of exposure to the virus. Although media and scholarship have hitherto focused on the public forms of marginalisation experienced by immigrant and refugee workers amidst the pandemic, such as their exclusion from healthcare coverage and financial relief measures, less attention has been paid to how the pandemic has reverberated along multiple dimensions of their private lives and domestic households. Within this group of people, refugee women face unique implications within complex systems of racial, cultural, national, religious, gender and class-based inequality in the country, and broader structures of gender inequality have especially exacerbated the vulnerability of refugee women and their families during the COVID-19 crisis. Refugee women in the United States typically work in client-facing low-wage jobs, which has threatened their paid employment due to closures of businesses in the country.

Mattias De Backer, Université de Liège, Belgium

This contribution is based on the testimonies of about 25 frontline workers who, despite the dangers associated with the COVID-19 pandemic, have continued to support vulnerable groups including: undocumented migrants, refugees, asylum seekers, young people in special youth care, homeless people, and overall, people in poverty. This research is part of a European, HERA-funded research project on 'The everyday experiences of young refugees and asylum-seekers in public space'.

Cevdet Acu, University of Exeter, UK

While the coronavirus has spread indiscriminately across the world, the negative effects have been felt differently, as COVID-19 has amplified conditions for some of the most vulnerable groups which, in Jordan, are mainly undocumented immigrant workers. Workers can lose legal status when they leave a permitted job for one in an underground economy, or become irregular workers because their visas allow residence but not employment. Undocumented workers are not fully protected by the legal regulations and are frequently exploited by employers through wage theft, sexual harassment and unsafe working environments. Unfair treatment such as low pay, inhumane work hours and denied payment for working overtime are regular occurrences in their lives, but beyond this, undocumented workers must now grapple with fears of transmitting COVID-19 and the restrictions that have come with it.

Emmanuel Raju, University of Copenhagen, Denmark

I left my home, my people and my land,

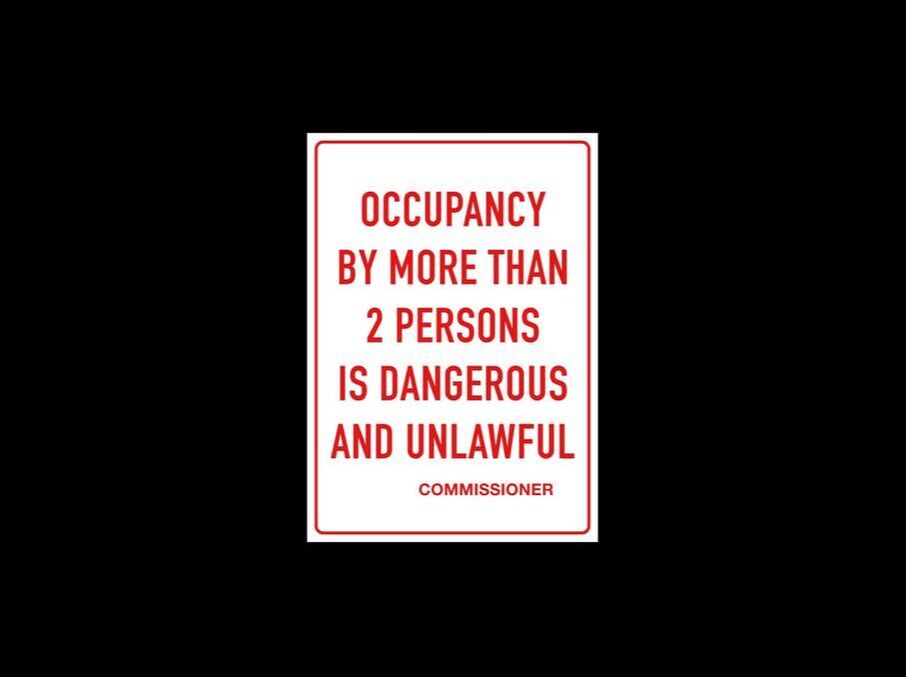

Searching for a ray of hope, a light through the tunnel, I fled poverty and marginalisation, I fled, looking for hope! I made a bed in a ‘slum’ as they call, I shared the shower with a million others, I shared my space with ten others, Space? Yes, just a fifteen square metres and a loft with another few men, Under the sheets of tin, we cooked, we ate and we worked, Fires and floods? Who cared? The virus came, they care! Not about me but that the virus might come into their home, Told me to stay home, they called it social distancing, they get paid for that, I don’t! And if we all stayed home in the slum, how do we distance? Clean water, I never saw that before! How do I wash my hands for 20 seconds without water? I don’t get to eat because I have to stay home, What do I do? Walk home no matter the distance. It was a few hundred kilometres I succeeded, no matter the heat, I collapsed once, some water came, then some food, Thank you Good Samaritan! Then came the barricades, to stop me, the migrant! Then came the sanitisers for the buses but they sprayed on me, Then came the canes, the police’s parade of power asking why am I walking, Because I cannot work from home, and if I don’t work, I don’t eat! They closed the borders and the sight of my real ‘home’ gone, Even if I had the virus, nobody cares because I have left the city, No water, no soap, no distancing, Unemployed, unpaid and starved, The poverty, my darkest fear that I fled, I see it come again, But I walk home, the long walk home!

Anjali Karol Mohan, India

'As in the photo of the daal packet, it is reassuring to see that there are civil society organisations that are promoting the message of equality especially during this time of crisis'.

Prior to COVID-19 taking centre stage as a global pandemic, a two-part seminar series called 'The "Southern Tilt" in the Urban Embedded Wisdom and Cultural Specificity as Pathways to Planning' was held in Colombia and India. The series sought to evolve planning approaches and methods to shape city futures in Latin America, Asia and Africa, geographies that promise to be the future of urbanisation. The main objective was to establish relevant and appropriate vocabularies, methods and processes to comprehend, steer and manage the emerging urban. Animated discussions on informality, migration, housing, land, displacement and conditions of displaceability had, in my opinion, made for a successful seminar. Six weeks later, however, while the discussions seem to be woefully inadequate in the midst of the COVID-19 outbreak, the objectives of the series could not have been more pertinent. Feeling of desperation is doubled due to COVID-19 among undocumented African migrants in Istanbul27/4/2020

Dogus Simsek, University College London, School of Slavonic and East European Studies, UK

A few days ago, I received a WhatsApp message from an undocumented migrant living in Istanbul stating that, 'Our situation is getting worse. I lost my job because of coronavirus. I am stuck here with my child. I do not know how I will pay the rent, buy food for my child. I do not know what to do if we catch the virus. We cannot go to hospital. We are stuck here with very limited facilities. I am very worried about our lives. There is no one to help us. Many of us who do not have documents feel very desperate at the moment'. This is probably one of the worst experiences she has gone through since she migrated to Turkey from Ghana. Trying to understand this feeling of desperation without the social, political and cultural context is hard.

|

Identities COVID-19 Blog SeriesExplore expert commentaries curated by Identities surrounding COVID-19 and displaced migration, nationhood and citizenship, and more. Blog Categories

All

|

Explore Identities at tandfonline.com/GIDE |

|