|

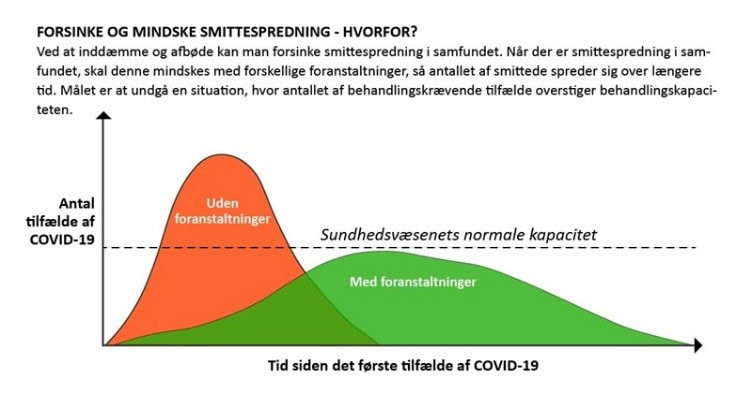

Ayo Wahlberg, University of Copenhagen, Denmark In biological terms, COVID-19 has proven to be extremely virulent for some (elderly and people with underlying medical conditions in particular), while very much less so for most others. Yet, in a socio-economic sense COVID-19 already ranks as one of the most virulent viruses ever, having thrust millions of people into unemployment (many of whom were already living highly precarious lives) and having brought healthcare systems in, among other cities, Milano, Madrid and New York City to the brink of collapse. In this essay, I suggest that the COVID-19 pandemic has laid bare failures of government rooted in decades of structural adjustment, austerity and commercialisation in healthcare throughout the world. Viruses are famously not fully alive, rather 'they verge on life' (Villareal 2008). For decades, biologists have sought to understand the mechanisms by which viruses parasitise host cells in order to multiply and spread. And while there are thousands of viruses, their pathogenic effects on human hosts range from ‘mild flu-like symptoms’ to deadly organ failure. Indeed, it seems that the effect of COVID-19 itself on those who contract it spans this entire spectrum of severity; extremely virulent for some (especially elderly, those with underlying medical conditions and likely also those exposed to large quantities of the virus such as frontline healthcare workers) and much less so for most others. Laboratories around the world are racing to understand just how this virulence might be stopped whether through a vaccine that inoculates the host thereby preventing spread or a treatment that inhibits COVID-19’s potentially life-threatening progression in a host. In the meantime, government after government has advised those most ‘at risk’ to self-isolate, urged all others to 'stay at home' and/or implemented emergency lockdown measures as ways to 'flatten the curve' and thereby mitigate potentially devastating effects on healthcare systems that are (at risk of) being overwhelmed by an influx of intensive care patients. More than half the world’s population is now restricted in its movements. Media reports from Wuhan, Lombardy, Madrid, New York City and London have been filled with images of overflowing intensive care units, exhausted frontline healthcare workers, convoys of ambulances carrying patients to hospitals, military trucks transporting the bodies of deceased and trench graves being dug out to cope with the sheer number of so-called 'excess deaths'. As we move further into 2020 and the COVID-19 pandemic continues to spread, every day and every week, country after country will experience its 'first wave peak', and we can be sure that more cities will be added to the list of 'overwhelmed'. Virulence is defined by cellular and molecular biologists as 'the relative capacity of a pathogen to overcome body defenses' (Merriam-Webster 1995). Put another way in a recent essay by Siddhartha Mukherjee, 'viral attack and the immune system’s defense are two opposing forces, constantly at odds… [there is] an ongoing battle between microbe and immunity' (Mukherjee 2020; see also Cohen 2009). Yet, if we were to re-centre our vantage point from the molecular to the societal, we might well speak of the virulence of COVID-19 in terms of its relative capacity to overcome entire healthcare systems. For, if there is one thing that we have learned already now, it is that responsibilising individuals to do their part by staying at home, maintaining physical distance and self-isolating has been the strategy of choice for most governments. Such a shifting of responsibility away from failures of government and towards the ‘failures’ of ‘irresponsible’, ‘non-compliant’ individuals has completely overlooked the fact that 'sheltering in place' and 'physical distancing' are a luxury of the few in a grossly uneven world where millions live on the streets or in living quarters that inhabitants do everything they can to spend as little time as possible in (see Fitzgerald 2020). While governments may well be scrambling to increase the 'normal capacity' of their health care system (i.e. raising the dotted bar in Figure 1) to deal with an influx of hospitalised COVID-19 patients, they have nevertheless been forced to rely on delaying spread by imploring their citizens to 'flatten the curve' given insufficient numbers of hospital beds, an acute lack of ventilators for oxygen therapy, and most importantly, scandalously massive shortages in personal protection equipment. What the COVID-19 pandemic has made abundantly clear is that, following decades of austerity and commercialisation of healthcare throughout the world, 'normal capacity' has absolutely nothing to do with being prepared for a pandemic, despite countless warnings from public health scientists (Caduff 2015; Lakoff 2017). Indeed, as the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) has pointed out 'in many European countries, the financial and economic crisis, which started in 2008, provided an additional stimulus to reduce hospital capacity in line with policies to reduce public spending on health' (OECD 2017: 172). We will do well to remember that talk of overstrained healthcare systems is in no way unique to the exceptional circumstances surrounding the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. As governments throughout Europe and America shift resources and priorities almost exclusively to addressing the COVID-19 pandemic, this comes at the cost of already stretched treatment and diagnosis of other conditions such as diabetes, malaria, cancer or heart disease. What is more, in less-resourced parts of the world, we know that ‘normal capacity’ is, at the best of times, exactly what has been the object of countless 'structural adjustment' and global health projects for over half a century now, leading to improvised, unstable and triaged practice of medicine on a daily basis (Livingston 2012; Nguyen 2010; Street 2014), let alone in emergencies such as those of the Ebola outbreaks in Africa which have 'devastated local health systems, strained humanitarian capacity and exposed the limits of global health governance' (Kelly 2018: 136). It is thus against backdrops of austerity, structural adjustment and commercialisation that we must situate the ongoing overwhelming of healthcare systems throughout the world. In a biological sense, while highly infectious, COVID-19 is far from being among the most virulent of known viruses (cf. Ebola or HIV), yet in social terms COVID-19 already ranks amongst the most virulent ever having brought healthcare systems in well-resourced parts of the world to the point of collapse; thrust millions (both those who were already living precarious lives and others who will now be doing so) into unemployment; left sufferers of medical conditions other than COVID-19 in limbo (and ironically ‘at risk’ of their known conditions while in self-isolation to protect themselves from the virus); and disproportionately exposed discriminated minorities and less well-off 'essential workers' to the virus itself. COVID-19 is just as discriminate as the healthcare, social and economic systems it is currently overwhelming. Given the unfathomable socio-economic consequences that are only just beginning to manifest themselves globally, there is a clear danger that unending austerity in health care and many other welfare services will take root. We must do everything possible to make sure that global resources, once and for all, are perpetually redistributed in ways that ensure the opposite. The virulence of COVID-19 has made it all too clear that we must build another world. Acknowledgments I would like to acknowledge the European Research Council (grant no. ERC-2014-STG-639275, The Vitality of Disease—Quality of Life in the Making). References: Caduff, C. 2015. The pandemic perhaps: dramatic events in a public culture of danger. University of California Press. Cohen, E. 2009. A body worth defending: Immunity, biopolitics, and the apotheosis of the modern body. Duke University Press. Fitzgerlad, D. 2020. 'Stay the fuck at home'. Somatosphere. http://somatosphere.net/2020/stay-the-fuck-at-home.html/, accessed on 15 April 2020. Kelly, A. H. 2018. Ebola vaccines, evidentiary charisma and the rise of global health emergency research. Economy and Society 47: 135-161. Lakoff, A. 2017. Unprepared: global health in a time of emergency. University of California Press. Livingston, J. 2012. Improvising medicine: an African oncology ward in an emerging cancer epidemic. Duke University Press. Merriam-Webster. 1995. Medical dictionary. Springfield, Massachusetts: Merriam-Webster Inc. Mukherjee, S. 2020. The one and the many. The New Yorker, 6 April 2020. Nguyen, V. K. 2010. The republic of therapy: Triage and sovereignty in West Africa’s time of AIDS. Duke University Press. OECD. 2017. Health at a glance 2017: OECD indicators. Paris, France: OECD Publishing. Street, A. 2014. Biomedicine in an unstable place: Infrastructure and personhood in a Papua New Guinean hospital. Duke University Press. Villareal, L.P. 2008. Are viruses alive? The Scientific American. 8 August 2018, https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/are-viruses-alive-2004/, accessed on 15 April 2020. Ayo WahlbergAyo Wahlberg is Professor MSO at the Department of Anthropology, University of Copenhagen. Working broadly in the field of social studies of health and (bio)medicine, his research has focused on reproductive and genetic technologies (in China and Denmark), traditional herbal medicine (in Vietnam and the United Kingdom), and health metrics. He is currently leading a 5-year European Research Council (2015-2020) project entitled “The Vitality of Disease – Quality of Life in the Making”. Ayo is editor of BioSocieties and author of Good Quality – the Routinization of Sperm Banking in China. Contact: Department of Anthropology, University of Copenhagen, Øster Farimagsgade 5, 1353 Copenhagen, Denmark. Email: [email protected]

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

The Viral Condition: Identities

|

Explore Identities at tandfonline.com/GIDE |

|