|

|

|

As a team of international scholars with Czech and US origins living in Czechia and Austria, the 2015 ‘refugee crisis’ hit us in contrasting ways with regard to different regimes and their attitudes towards refugees from Syria and other Middle Eastern countries. While Czechia accepted just twelve refugees under the EU’s quota system, the Austrian public broadcasting station FM4 changed its jingle from ‘You're at home, baby’ to ‘Refugees, welcome’.

Seven years later, as we finalized work on our Identities article, ‘I always felt I have something I must do in my life’: meaning making in the political lives of refugee non-citizens’, the situation had somewhat reversed. In the spring of 2022, the streets of Prague were filled with Ukrainian flags, Czechia had accepted over 300,000 refugees in just a few months, and people became emotional regarding the war, while Austria, as a ‘neutral’ country and a non-member of NATO, was considerably more reserved.

0 Comments

The arrival of large numbers of Ukranian refugees fleeing the Russian invasion to their country since February 2022 has been met with a wave of compassion and solidarity in most western European countries. However, critical voices have pointed out what has been perceived as hypocrisy, or a ‘double standard’, regarding attitudes towards refugees. Why are some of them welcomed with open arms, while others are being repressed at the border? While Ukrainians could fast-track their asylum claims and enjoy protection status with minimum requirements, people fleeing other conflicts in the Middle East and Africa were still getting stuck in lengthy bureaucratic processes and often becoming the object of resentment and discrimination in the host society. Is this so because of racial difference?

The increased arrivals of refugees in a short span of time reminded many in Europe of the peak of arrivals from Afghanistan and Syria in the mid-2010s. Public opinion in various western European societies of alleged unbridgeable cultural differences or difficulties towards ‘integration’ of the newly arrived did not apply to Ukrainian refugees. While Ukrainians, critical voices argued, were perceived in the mainstream public opinion as ethnically, culturally and racially close to western Europeans, other victims of armed conflict equally entitled to protection were still represented or perceived as ‘less deserving’ by social and political actors holding anti-immigration positions. This shows the extent to which the way migrants are portrayed in Europe is a highly contested matter that connects deeply to values, perceptions and anxieties permeating those societies.

Earlier this year, Home Secretary Suella Braverman announced she was not proceeding with multiple recommendations made by Wendy Williams’ public inquiry into the Windrush Scandal. The inquiry examined the Home Office’s adverse actions against people from the Windrush generation who predominantly migrated to Britain from the Caribbean between 1948 and 1973 (Gentleman 2019; Slaven 2022). Reports have detailed the profound effects on those directly impacted, revealing stories of individuals who were denied healthcare and welfare services, and in some cases were ripped away from their families; detained and even deported (Gentleman 2019; Williams 2020; Slaven 2022). The ensuing scandal thrust their treatment into the public consciousness and ignited a public uproar. Yet, as the scandal faded from media attention, we still have a limited understanding of the scandal’s broader impact on Britain's racialised communities, beyond those directly affected by the Home Office’s actions.

One glimpse at minority language protection: the fine line between empowering and segregating24/5/2023

On 5 November 2022, the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages celebrated its 30th anniversary. This charter lays down the principles for protection and promotion of minority languages and their use in education, cultural life, public services, and other sectors within the EU. Undoubtedly, such supra-national and similar national policies generally improve the rights and lives of minority members.

My Identities article, ‘Drifting borders, anchored community: re-reading narratives in the semiotic landscape with ethnic Lithuanians living at the Polish borderland’, discusses a concrete example of one such minority protected on national and supra-national levels – the national Lithuanian minority in Poland. I provide a glimpse into the realities of its members’ language use, identification and narratives of belonging. I learned that they find some official minority protection attempts more concerning than helpful.

What does a Thai person look like? How do expectations about citizenship create an ethicized cultural phenotype? In our Identities article, ‘Turbaned northern Thai-ness: selective transnationalism, situational ethnicity and local cultural intimacy among Chiang Mai Punjabis’, we explore family histories, selective transnationalism and regional Lanna identities among Thai citizens with Punjabi heritage and selective cultural identity. This article argues that Punjabi Thais maintain their networks and cultural connections with a historic ancestral homeland, but they also cultivate forms of local cultural intimacy in ways which leapfrog the linguistic and cultural hegemony of Thai national identity. In other words, despite their non-Thai appearance, these Punjabi Thais have deeply local cultural knowledge, speak Northern Thai language fluently and have Northern Thai cultural sensibilities.

Recent UK Home Secretaries have condemned the toppling of a slave trader statue in Bristol, dismissed footballers taking the knee as ‘gesture politics’ and called on police forces to spend less time on diversity and inclusion initiatives. Yet between 2010, when the Conservatives came into power, and 2020, the overall policy framework remained broadly favourable to multiculturalism: accommodations are still made for ethno-religious dress, the BBC has retained its mandate to reflect diversity, and funding is available for ethnic organisations.

With respect to immigration, there has been a closer connection between harsh rhetoric and restrictive measures, exemplified by the multiplication of immigration checks, the end of free movement with the EU, the housing of asylum seekers in inadequate and overcrowded military barracks and the on-going attempt to deport some to Rwanda. At the policy level, therefore, efforts to include racialized citizens seem to have become disconnected from the opening of the country to foreign nationals. Shift the focus from the Government to minority ethnic and anti-racist organisations, however, and the picture starts to look quite different. In September last year the Muslim Council of Britain echoed a report from the Institute of Race Relations denouncing how British Muslims were disproportionately affected by the citizenship deprivation powers reinforced through the Nationality & Borders Act 2022. The Runnymede Trust, a leading race equality think tank, has published a number of blog posts denouncing deportations and asylum-seekers’ woeful living conditions, partly due to the denial of their right to work and access public funds. Similar claims have been raised by Voice4Change, an advocate for the Black and minority ethnic voluntary sector.

During the 2019 debates around the introduction of the EU Settled Status (EUSS), which regulates the rights of EU citizens in the UK after Brexit, Labour MP Yvette Cooper described the scheme as a potential ‘Windrush on steroids’. The reference was to the ‘Windrush generation’ scandal, in which Commonwealth citizens, who arrived in the UK with a permanent right to stay, were classified as unauthorised migrants, deprived of the right to work, rent or access welfare, and in some cases deported. The Windrush generation scandal has focused on people who arrived from the Caribbean, and the publicly known cases and data on compensation applications show that Jamaica has been the single most common country of origin. However, it is not possible to determine precisely the extension and geographical profile of the scandal, also because of the initial refusal of the Home Office to review historical cases beyond the Caribbean to identify potential unjust treatments.

The Windrush generation scandal is mainly the result of the ‘Hostile Environment’ policy, which extends and multiplies controls of migratory status. As the Hostile Environment encourages targeting racialised groups, it can be seen as a continuation of the racism to which the Windrush generation has been subject since their arrival in the UK. The ambiguous status of those Commonwealth citizens – who arrived with British passports but less rights than the British-born, and the limited documentation of their status, made them further vulnerable to the injustices they underwent. The argument of the critics of the EUSS is that, as the status does not come with a physical document, and is digital-only, this endangers EU citizens in the UK to be in the future miscategorised and mistreated as happened with the Windrush generation. In my recent article for Identities, ‘The vulnerability of in-between statuses: ID and migration controls in the cases of the Windrush generation scandal and Brexit’, I use several documentary sources and interviews with EU citizens in the UK and British citizens in Belgium to explore the degree to which Brexit and the Windrush generation scandal pose similar questions in terms of ID and legal status.

On 7 March 2023, UK Home Secretary Suella Braverman, escalating the rhetoric on and punitive approach to migration, asylum and refugees, announced the ‘Illegal Migration Bill’ and strategy to stop migrants crossing the Channel in small boats by arresting, detaining, deporting and banning those caught. In response, former football player and BBC Match of the Day (MOTD) Presenter Gary Lineker tweeted that it is ‘an immeasurably cruel policy directed at the most vulnerable people in language that is not dissimilar to that used by Germany in the 30s’. The tweet led to a backlash in which responses ranged from the claim that he was operating beyond his remit as a sport presenter (as if they have not had to discuss racism and nationalism before), that he was in breach of the BBC’s impartiality rules, and that the comparison was unhelpful. Keir Starmer, Leader of the opposition Labour Party stated: ‘I think comparisons with Germany in the 1930s aren’t always the best way to make one’s argument’. Others took offense and expressed shock that anyone could associate Britain and the current government with the lead up and precursors to Nazism and the Holocaust. Some claimed that Lineker actually referred to these explicitly in his tweet, which he did not. Former Conservative MP for Stoke-on-Trent Jonathan Gullis claimed that Lineker was calling ‘people up here’, referring to Northern ‘Red Wall’ voters, which Starmer and Labour are also targeting with anti-immigration rhetoric, ‘racist bigots, Nazis’. According to Matthew Goodwin, Lineker’s comments are an example of how out of touch the ‘new elite are from the majority of the ‘people’ from the ‘Red Wall’ to ‘Tory Shires’, and particularly those at ‘the bottom’: ‘the white working class, straight men, non-graduates, and those who cling to more traditionalist views, such as supporting Brexit’.

From the institutions to the streets: the role of emotions in Barcelona’s migration control8/3/2023

In her essay The Cultural Politics of Emotions, Sara Ahmed raises the question: ‘What do emotions do?’, implying the social circulation of emotions. Even if felt by each individual in a unique way, emotions are addressed collectively, creating affective connections which in turn craft social realities.

There is a diverse range of institutions and practices that make up migration control in Barcelona. Despite the claim that it is governed by the rule of law, where there is no room for subjective or accidental decisions, emotions play a key role. What do a practitioner employed by a municipal institution in charge of migrant inclusion and a person categorized as a migrant with precarious legal status share, when they meet face to face? They do not know each other and they have never met before, but a bond is assumed to be created between them. They find themselves in an unequal power relationship, since the institutional practitioner has the power to decide through their intervention on the fate of their interlocutor. What is left in this connection which is not direct or spontaneous, but rather mediated by protocols and paperwork, and in which each person already has an assigned role which he/she plays or contests? I tried to answer these questions in my Identities article, ‘Back in order’: the role of gatekeepers in erecting internal borders in Barcelona’, exposing the role of emotions in migrants’ control in urban space, what I understood as a bordering practice.

Motivated by a need to think in terms of consequences, the language of ‘adaptation’ has become key in approaches tackling climate change.[i] While discussion of adaptation has an older provenance[ii], bodies such as the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) have adopted it with a justified urgency, and in ways that have seen adaptation enlisted by diverse actors – and across a variety of approaches – much as if it were a ‘chameleonic’ concept’. That is to say, approaches called adaptation appear ‘able to move further into policy either because they overtly complement institutionalized ideas’ or have ‘chameleon-like qualities which facilitate their translation into policy’.[iii] This understanding helps explain the seeming appeal of the concept but also contains clues as to why prevailing adaptation approaches have been inattentive to the racial determinants of vulnerability to climate change.

As a scholar of migration who had spent several years doing research in Berlin, I have always been interested in the question of displacement in West Africa. I had met many migrants who had arrived from West African countries such as the Gambia, Senegal and Guinea-Bissau in Berlin. It is a well-known fact that significant numbers of people risk perilous journeys to reach Europe. Hence, in collaboration with two researchers I decided to conduct a study in Senegal in order to find out how, why and to what extent small-scale fishers become displaced. Prior to undertaking the research, I had visited Senegal for a holiday and had acquired a fair idea of some of the socio-political issues in the country.

We were fortunate enough to receive some small-scale funding from centres such as MIDEX and C4Globe. We were also fortunate to connect with an interpreter/research assistant in Senegal who spoke English, French and Wolof and assisted us with methodological approaches, conducting interviews and with transcription. He had friends and family in all three of the villages where we did our research, and we had several follow-up questions even after the interviews were conducted. As researchers from the Global North we were aware of our privileged positions, but at the same time the two European-based researchers originated from Nigeria and Pakistan which had a bearing on some of the power dynamics.

In our Identities article, ‘I became a Taiwanese after I left Taiwan’: identity shift among young immigrants in the United States’, we seek to engage with transnationalism literature, which argues that migrants continue to remain concerned with their origin country. As our case study shows, successful assimilation into the host country does not mean migrants will relinquish their previous attachment. In fact, fresh experiences abroad might actually activate and intensify their homeland identity. Our study documents unpleasant contacts with people coming from People’s Republic of China (PRC) and personal experiences with the immigration rules that favour Taiwanese. Our interviewees also share the disenchanting discovery that America was actually lagging behind Taiwan in terms of healthcare, public transportation and recycling, which encourages these young migrants to cherish heir Taiwanese identity. In short, being Taiwanese is something one can take pride of, and therefore, our interviewees explained they do not want to be viewed by people from PRC as their 'compatriots’ or identified as ‘Chinese’ by their American friends.

After China turned into a popular migrant destination, foreign-Chinese couples became a common sight on the streets of Chinese cities. In my early years of living in China, as a language student in Beijing (2005-2009), I already developed an interest in the romantic relationships I would later study as an anthropologist. My circle of friends included many Chinese-foreign couples, and our love lives were a favourite topic of conversation. These conversations were often marked by circulating beliefs about dating in Beijing for foreigners, such as the idea that Chinese women liked white men, but white women did not like Chinese men. This idea was both widely shared and regularly challenged by couples who proved the opposite. We also debated the contentious position of the white man in the Beijing dating scene. Was he wildly popular for being perceived as rich, handsome and worldly by Chinese women? Or was he regarded with suspicion for possibly being a player or a benguo luse (本国卢瑟)? This term translates to ‘loser back home’ and is popularly used to undermine the admiration that is perceived as being extended to white men too easily.

In 2018, the research department of Awel, a Flemish civil society organization, published a report on the impact of the late terrorist attacks in Europe on the identity formation of minority youth. The report, based on testimonials, revealed that some Muslim children try to hide their ethno-religious background out of fear of being verbally attacked. Some even wish to ‘unbecome’ Moroccan or Muslim to respond to Islamophobia.

The largest ethnic minority group in Belgium originates from Morocco. This primarily Muslim group is indeed strongly stigmatized, even more so since 9/11. It is argued that terrorist attacks increase Islamophobic or anti-Muslim sentiments, which hence also impacts the well-being of Muslim children living in Flanders. The findings of the research report nevertheless did not receive as much public and political attention as deserved. Yet, ethnic minority citizens’ identity formation has long been a subject of political interest, especially since many politicians across the spectrum propose that minorities, and particularly Muslims, do not identify as Belgian.

The Facebook group for my local area in Manchester generally has messages about missing cats and people looking for recommendations for plumbers. But there are also messages asking ‘what is it like to live in the area’ from people thinking of moving there. This is a very ethnically mixed, relatively deprived area which has an equally mixed reputation. The responses to the queries often refer to reputational issues – and ones of history, suggesting that the area has/has not changed over time. The live nature of histories of place and the ways in which stories about places are frequently racialized is what colleagues and I were concerned with in our recent Identities article, ‘Histories of place: the racialization of representational space in Govanhill and Butetown’. We were interested in considering the racialized nature of Henri Lefebvre’s[1] conceptualizations of spatial tactics, representations of space and representational space – including in the way they are marked by the past.

We examined interviews with local activists, community representatives and professionals working in the areas of Butetown in Cardiff and Govanhill in Glasgow which were part of a study of the dynamics of ethnic inequalities for the Centre on the Dynamics of Ethnicity (CoDE). Both areas have long histories of immigration and, as representational spaces, have often been highly racialized. They have been shaped by industrialization, empire, de-industrialization and then some subsequent regeneration.

Young people in ethnically divided post-conflict societies are often happy to date across ethnic lines, notwithstanding its prevailing discouragement. My recently published Identities article, 'Kiss don't tell: attitudes towards inter-ethnic dating and contact with the Other in Bosnia-Herzegovina', examines this in Bosnia-Herzegovina, which it takes as a typical case of an ethnically divided post-conflict society: young people struggle to meet other ethnic groups due to the high levels of segregation in society. Such contact is also discouraged in the home, in schools, in religious institutions and in the media. I use focus groups conducted on Facebook and follow-up interviews to speak to young people across the country who date across ethnic lines despite these obstacles.

‘Identity’ is probably amongst the most circulated terms in the academy and beyond. However, a critical reflection on the use of this term in the context of cross-cultural fictional narratives could reveal a major issue. Rather than representing a genuine state of human condition, the term has become a strategic means used by some minority writers to boost readership for their writings.

Given the hierarchies of the world literary system consisting of influential agents such as critics, publishers and marketing expectations, certain languages, regions, styles and poetics are privileged over others. The world literary system thus mirrors the ‘neo-imperial contours of global capitalism’, dominated by multinational publishing conglomerates with powerhouses in London and New York. My Identities article, ‘We have much identity’: contesting the claimed hybrid identity in Faqir’s My Name is Salma and Ahdaf Soueif’s In the Eye of the Sun’, examines how some Arab Anglophone women writers manipulate identity constructions and essentialise their hybrid identities as a strategy to boost readership and market values for their works. Through a close reading of Fadia Faqir’s My Name is Salma and Ahdaf Soueif’s In the Eye of the Sun, the article reverses the gaze on the societies that these texts claim to reveal.

Migration enforcement is accompanied by emotions expressed by various actors – including the broader public, politicians and those targeted by practices such as deportation and detention – but also those of bureaucrats who implement policies. Emotions are addressed towards or expressed against a multitude of groups, such as asylum seekers or migrants with precarious legal status, as well as police officers and administrative and non-governmental staff.

Studying emotions directed at different groups uncovers, on the one hand, the intricate and complex network of actors working within the field of migration enforcement, both new and old. On the other hand, it presents the researcher with a density of relations that, as I argue in my Identities article, ‘Tracing the circularity of emotions in Swiss migration enforcement: organizational dissonances, emotional contradictions and frictions’, can be analyzed through a focus on emotions, thus advancing our understanding of statecraft and organizational construction.

Thanks to decades of critical scholarship in the social sciences, it is now common for scholars to reflect on their positionality vis-à-vis research topics and subjects and to demonstrate awareness of the power structures that shape their knowledge production. While this often amounts to deliberations about one’s individual identity in terms of race, gender, class, sexuality, ability, etc., scholars are rarely expected to question the ideological assumptions that underpin how they, both as individuals and as members of societies, make sense of the world. Taking certain ideological positions for granted as universal – liberal, secular, individualist, etc. - presents a problem in the study of political life-worlds that claim to offer alternatives, especially those with revolutionary system change on their horizon.

In my Identities article, ‘Stateless citizenship: 'radical democracy as consciousness-raising' in the Rojava revolution’, published in the special issue ‘Radical Democratic Citizenship: From Practice to Theory’, I write about ways in which protagonists of the self-determination system that has been in the making in majority Kurdish regions of Northern Syria since 2012 imagine their political struggles as a long-term effort for liberation from capitalism, patriarchy and the nation-state. I argue that this amounts to a decolonization effort that – in the words of my interlocutors – beyond the concrete work of building institutional infrastructure, aspires to transform dominant ‘mentalities in society’, including patriarchal and statist thinking which developed over thousands of years of power and domination. While sharing fragments from my fieldwork in Rojava, I decided to consciously center the ideology of the Kurdistan freedom movement, as articulated by imprisoned political leader Abdullah Öcalan, in my conceptual framework.

Cross-posted by RACE.ED

‘We are now in the age of Du Bois’, declared Aldon Morris in his widely acclaimed study, The Scholar Denied: W. E. B. Du Bois and the Birth of Modern Sociology. In this, Morris meticulously charts the intellectual contribution of Du Bois (1868-1963) to the social sciences broadly conceived, and sociology in particular, to argue that this remarkable figure could no longer been treated as peripheral, or an ‘add on’. After all, few sociologists pioneered as much as Du Bois, including in, amongst other areas, both quantitative and qualitative methodologies, especially social statistics and urban ethnography, reconciling questions of political economy with social movements (not least in charting the suppression of Atlantic slavery), as well as foregrounding relationships between the self and society, and doing so in ways that prefigure questions later posed in the politics of recognition. For these reasons I am not alone in arguing that Du Bois has bequeathed to sociology a cluster of normative categories that compel us to move beyond a kind of formalistic inquiry, and through which we might be more open to uncovering sometimes submerged features of social life (1).

A number of different aspects of identity are relevant to young people, from self-esteem, distinctiveness, self-concept, clarity, coherence and self-continuity. We recently published a paper in the Journal of Social Psychology Research on the importance of the social context as a component self-continuity. Using young adults (ages 19-25) from the US and Brazil, our latest research demonstrates that the social context, specifically our friends and family, is a novel, measurably distinct self-continuity strategy. In particular, the results from our study exemplify that relationships continue to play an important role in healthy identity development.

Emerging adulthood refers to the period of early adulthood between the ages of 18 and 25. Specifically, it’s characterized as an age for exploring different identities, within the contexts of school, work and romantic relationships, to name a few. Due to the changing roles during this period of the lifespan, this is also an age exemplified by instability. Beyond that, emerging adults can feel in-between adolescence and adulthood, that this is a period of their lives to focus on themselves and that the future contains a range of possibilities for them. As such, this makes for a crucial period to study identity development.

Gender, as expressed on namely the bodies of Muslim women, is positioned at the centre of the radical right’s linkage between migration and religion. This link is visible in the persistent debates on the ban of Muslim body-covering, which in Austria has been promoted by the Austrian Freedom Party (FPÖ) since the turn of the century.

FPÖ’s debates on the ban of Muslim body-covering – of the headscarf in kindergartens and schools or of full body-covering in public spaces – which re-emerged since 2015, illustrate that the radical right instrumentalizes the intersection of gender, body and religion in its search for new forms of governing. As I explore in my recently published Identities article, ‘Radical right populist debates on female Muslim body-coverings in Austria. Between biopolitics and necropolitics’, the radical right’s debates over female Muslim body-covering are embedded in the neoliberal reorganisation of societies and a crisis of governability, which radical right-wing actors use to implement their own biopolitical and necropolitical projects.

The COVID-19 pandemic profoundly transformed people’s lives, identities and practices throughout the world. It had particular effects on the group of international students who usually move frequently between home country and study destination. When the pandemic hit their study destinations in 2020, they had to take immediate action and plan migratory trajectories accordingly.

Chinese international students (CIS) also experienced a nationwide pandemic control policy at home that caused continuous travel constraints on international flights and passengers landing in China. The domestic policy had a profound impact on their migration aspirations – to remain in the study destination or to return home. Simultaneously, students reconfigured their perceptions of homeland. Our research, as detailed in our Identities article, ‘Migration aspirations and polymorphic identifications of the homeland: (Im)mobility trajectories amongst Chinese international students amidst COVID-19’, includes semi-structured interviews with 33 CIS studying in 23 cities of 10 European countries (including the United Kingdom). We aim to understand how students’ identifications of homeland – a cognitive assemblage of emotions, commitments and reflections towards their home country – intersect with their migration aspirations.

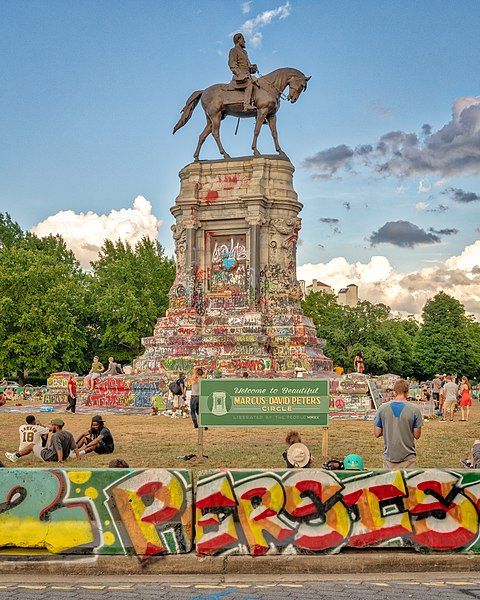

On 8th September 2021, a crowd gathered on Monument Avenue in Richmond, Virginia, USA, near the base of its iconic statue of Confederate General Robert E. Lee. The atmosphere in the crowd was jubilant as workers positioned a crane, wrapped the statue in a harness, and finally–after an hour of preparation, a year of court cases, and 131 years of racial terror set in stone–pulled the statue down from its plinth.

The equestrian statue of Robert E. Lee, Commander of the Confederate Army, is, and always has been, a symbol of white supremacy. Its removal creates the opportunity to change the meaning of the space it once occupied. For the past year at the Centre on the Dynamics of Ethnicity (University of Manchester), we have interviewed activists, policymakers, and cultural workers involved in contesting fourteen statues of slavers and colonisers in five countries. We have also explored the meanings of statues of empire and colonialism with young people from Manchester Museum’s OSCH Collective who shared how statues of white supremacy in towns and cities they call home impacted their sense of belonging. Our research highlights how anti-racist activists draw from global movements to contest local histories and memories. Equally, we consider how strategies for removing Confederate statues in the US (for example) might provide lessons for challenging imperial statues in the UK.

Romania has several multicultural regions, including the Banat in the southwest. During its time as part of the Habsburg and Austro-Hungarian Empires (1718-1918), cultural influences and economic developments from the West (German, Austrian, and Hungarian) made it an attractive destination for migrants. This continued after the Trianon Treaty and Romanian unification in 1918, as Banat was economically advanced compared to other regions to the East and South. Rapid industrialization and urbanization under the communist regime (1947-1989) and the subsequent removal of restrictions on movement in the early post-communist period also saw steady internal migration patterns.

Despite this long history as a recipient of migrants and cultures, the sense of nativism and place belonging is strong among Banateni. Proximity to Central Europe also led to a sense of discrimination, as Both noted, a Banat resident ‘would better prefer a German, Serbian or Hungarian than a migrant non-Banat Romanian’ in their village. In our recent Identities article, ‘Internal migration and stigmatization in the rural Banat region of Romania’, we attempted to uncover attitudes towards internal migrants and how these were understood by migrants themselves in rural Banat. |

|

Explore Identities at tandfonline.com/GIDE |

|

The views and opinions expressed on The Identities Blog are solely those of the original blog post authors, and not of the journal, Taylor & Francis Group or the University of Glasgow.