|

|

Where can Others turn? On (de)coloniality, messy refusals and alternatives to Eurocentric modernity19/7/2023

Blog post by Ali Kassem, National University of Singapore

Over the past years, decolonization has emerged as a key project, discourse, and buzzword across academic and public debates. Within this has been a growing recognition of the nature of Eurocentric hegemony, ongoing global connected coloniality and various pressing global crises. A growing movement to contest Eurocentric modernity and its narratives across scales: from anti-racism to ecological resistance has consequently grown and been increasingly hollowed, demonized and attacked. In researching forms of inequalities and racisms in Lebanon, focusing on the country’s Muslim communities, my research has identified a significant anti-Muslim racism pervading the lives of Lebanese Muslims. Deeply structured by and entangled with Eurocentric/modernity coloniality and articulated at the intersection of the (historical and contemporary) local and global, this anti-Muslim racism emerges as a key axis of coloniality’s assault, erasure and violence at the level of everyday lived experiences. Bringing to fore the presence and prevalence of anti-Muslim racism within the Arab-majority world, the eastern Mediterranean and Muslim communities themselves, my work has offered a series of contributions in rethinking the so-called Middle East, racism and Islamophobia studies, as well as the global workings of coloniality beyond the Atlantic.

0 Comments

After living in Miami, Florida, for several years, Mother Frances Butler returned to her home in Nassau, Bahamas and founded the Mother’s Club, which provided social welfare support to the Bahamian Black community. Along with similar groups, the organization offered a variety of social services where they fundraised as a part of hurricane recovery, aided the war effort and offered health and other social services for women and children. In 1937, Mother Butler changed the title of her organization to The Young Women’s Christian Association.

The building that formerly housed the Mother’s Club sits at the corner of Goal and East Street in the heart of Nassau. The building is in the Grants Town community and was originally established by the Bahamian government to house freed people and Liberated Africans in the early 1820s. This area is one of the communities located in what is known as the ‘Over the Hill’ neighbourhoods in Nassau. These neighbourhoods became a rich site of Black life during the 19th and 20th centuries, as Black people in the Bahamas encountered poverty and racial oppression. Mother Butler also founded other Black-led organizations, including the Young Men’s Christian Association and the Silver Bells.

Coloniality deserves special attention to contextualise Professor Hempton’s lecture on “Women’s Networks: Opportunities and Limitations”. First, the context that overlaps historical and political elements: the year 1888. The poster at the back of Professor Hempton as he delivered the talk informed that the Gifford Lecture series dates from 1888. In the same year, Brazil declared the Abolition of Slavery – the last country in the Americas to officialise such law that is not fully put into practice as many cases of forced labour and slavery remain current.

That reminded me of so many unofficial Black women’s collectives who organised as a quilombo, favelas communities, marginalised neighbourhoods (periferias) as they created ways to resist and refuse the places that the colonial-hegemonic society imposed on them. For example, the Herstories of Dandara and Luiza Mahin. Dandara refused to be enslaved and became a quilombo leader, a warrior, agriculture worker in the initial land rights, abolitionists, antiracist and feminist movements in Brazil during the late 1600s. Luiza Mahin was a Muslim, enslaved domestic worker, strategist of one of the most remarkable pro-abolitionist revolutions in Brasil – the Malês Revolt – organised by enslaved peoples. Her Islamic, Jêje-Nago and Yoruba backgrounds are the marks of intersecting systems of beliefs that to this day are erased in the narrative about Brazil’s national identity.

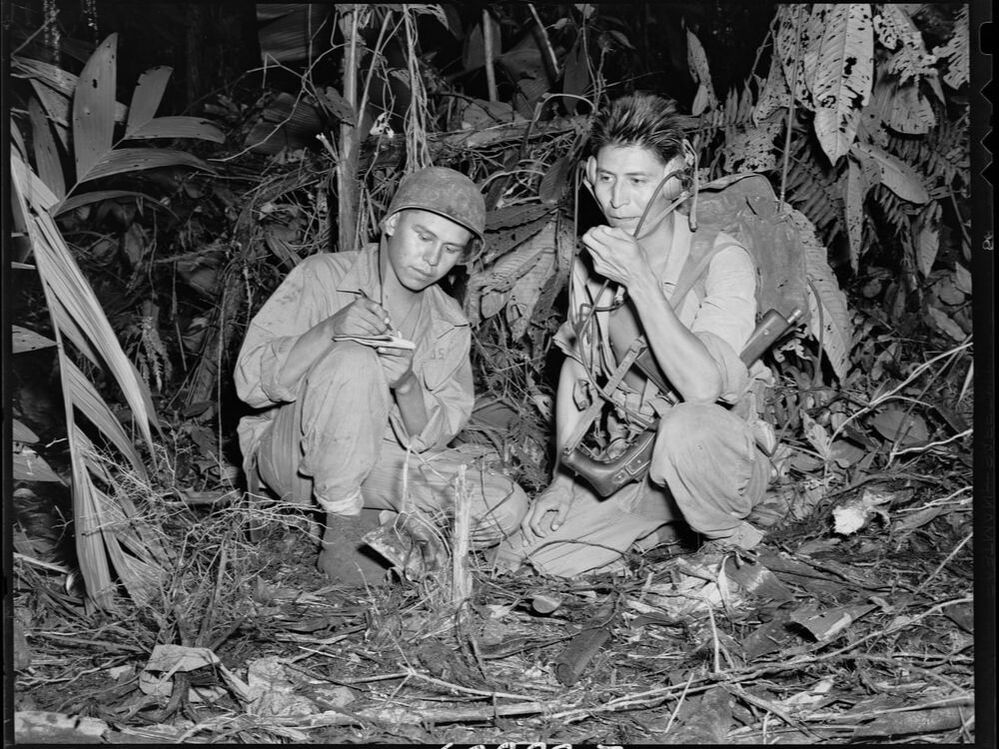

The global Indigenous Rights movement emerged late in the twentieth century, with scholars tracing its origin to postwar international conventions and human rights activism. In my Identities article, ‘World War II and the development of global indigenous identities’, and in a forthcoming book (War at the Margins, University of Hawai’i Press, 2022), I examine how the war created conditions favouring the emergence of Indigenous identity as a form of global political action.

The Second World War mobilised human and natural resources on a massive scale; its aftermath dissolved empires and rearranged the international order. Indigenous men and women — those in small-scale, often tribal, societies at the fringes of national or imperial control — were drawn in as soldiers, scouts, laborers and victims. New Zealand’s Māori Battalion, Navajo codetalkers in the US Marines, Naga guides for the British Army, New Guinean carriers for Allies and Japanese — these and other Indigenous actors shaped the progress, and sometimes the outcome, of campaigns. Even where front lines did not cross Indigenous homelands, civilians suffered violence, displacement, military occupation, economic and social disruption and forced labour. War created a fluid context for change, highlighting the ambiguous legal position of Indigenous people and altering government and public views of them.

Cross-posted from British Sociological Association

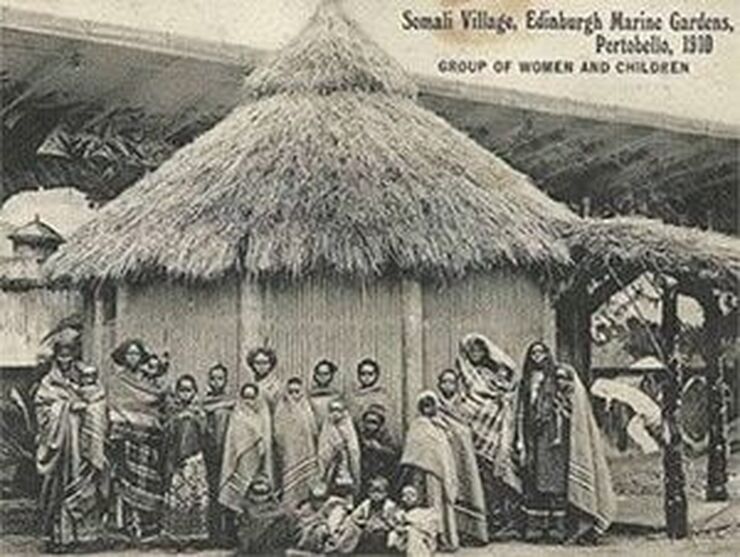

How is history written and by whom? These are questions that have been raised with frequency across the decolonising movement and in particular, by the Cadaan Studies movement, which has focused on knowledge production relating to Somali people. Started in 2015 by Harvard doctoral candidate, Safia Aidid, the movement provides a framework through which to critique the role of whiteness and white privilege in shaping narratives about Somali people. The canonical work of Glaswegian-born I.M. Lewis has come under particular scrutiny not in the least due to his twin roles as anthropologist and administrator for the British colonialists in (then) British Somaliland in the 1950s. Yet whilst the colonialist activities of a Scotsman in Somalia shaped global discourses about Somali people, the narratives of Somali people in contemporary Scotland, many of whom now live in the same area of Glasgow in which Lewis was born, remain absent from local and transnational histories. We unravel and critique this absence. Today in Scotland, there is a Somali population of up to 4000 people. The population has grown in the main since 1999, following the state-enforced dispersal of asylum seekers to sites around the UK. Despite residing in Scotland for nearly two decades, the Somali population continues to be framed in these terms, considered ‘new’, as ‘migrant’; as without history prior to arrival in Scotland and without historical links to Scotland. These narratives obscure a much longer history of Somali people living in Scotland, and of Scotland’s relationship with Somalia.

Cross-posted from Georgetown Journal of International Affairs.

Recent events in France have revealed how race remains such a loaded concept in French society. But policymakers must emphasize that this is nothing new, and that public policies need to address historical and present racism in France in order to move forward. Events in recent months have once again made race and racism part of public debate in France. There was the beheading of school teacher Samuel Paty in a banlieue, or suburban outskirt, north of Paris in October 2020. Then the beating, captured on video, of Michel Zecler, a forty-one-year-old Black music producer, by four police officers last November in Paris. These debates have even included accusations of importing Anglo-American or US conceptions of race and racism to the French context, as evident in a recent interview with President Emmanuel Macron in the New York Times and movement by his administration to investigate French universities for importing American theories. This is in addition to a proposed bill making it a criminal offense to share images of police officers on social media platforms, amid a growing mobilization against police violence targeting Black and Maghrébin-origin individuals.

The 550 days of communication blockade that Kashmir witnessed between 5 August 2019 and 5 February 2021 was unprecedented - the longest ever communication blockade in the history of any democracy. Coupled with intimidation, threats and restrictions on movement, the Indian state makes it too difficult for the media to operate freely in the region.

In my Identities article, ‘Communication blackout and media gag: state-sponsored restrictions in conflict-hit region of Jammu and Kashmir’, I highlight the events after the abrogation of Article 370 and its impact on press freedom in the region, especially to understand the perception of local journalists reporting from ground zero post-August 2019. On 5 August 2019, the Narendra Modi led government revoked Article 370 of the Indian constitution that provides quasi-autonomy to the region. In a broader neocolonial context, the abolition of Kashmir's autonomy is also the culmination of the Hindu indigeneity ideology, according to which Muslims on the Indian subcontinent are portrayed as invaders and foreigners, and Kashmiri Muslims are doubly marked as the Other: first as Muslims, and second as Kashmiris committed to an unrelenting struggle for a UN-mandated plebiscite and democratic sovereignty.

The recent visit by Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi to Bangladesh to attend celebrations marking 50 years since the birth of the country following the Liberation War in 1971 has drawn attention to the difficult task of building a nation on the back of a brutal and bloody civil war. At least four people were killed by police in the Bangladeshi city of Chittagong during a demonstration against Modi’s visit. Protesters from Hefazat-e-Islam Bangladesh, and counter protestors aligned with Bangladesh’s governing Awami League party, represent the central divide in Bangladeshi politics, between those who tie national identity to Islam and those who tie national identity to ethnicity and the Bengali language. This is a divide sometimes understood as one between those who ‘collaborated’ with the Pakistani military and those who participated in the independence struggle. On the Golden Jubilee of Bangladesh’s birth, this divide continues to shape Bangladesh’s political landscape today.

Using the case of the ‘Urdu-speaking minority’ in Bangladesh, my Identities article, ‘Displacement, integration and identity in the postcolonial world’, considered what the experience of minorities displaced during the Liberation War tells us about the Bangladeshi national imagination today. Their own voices, and the narratives of identity and integration in which they are situated, are revealing of the nature and boundaries of the nation state fifty years on from the country’s birth. Although the country remains divided around the role or significance of religion versus culture, and between those who ‘collaborated’ with the Pakistani military and those who participated in the independence struggle, there are older divides at work here too. Some of those who ended up on the wrong side of the Liberation War are accepted into the nation today. Here colonial narratives of ‘population’ versus ‘people-nation’, ‘community’ versus ‘citizen’ structure exclusion not only through narratives of the country’s foundation myth (as commonly assumed) but also through poverty and social space.

The territorial realization of the Israeli state produced a new category of stateless people: Palestinian refugees. Those expelled from their homes, villages and land during the onset of the Nakba (catastrophe): a large scale ethnic cleansing process executed in 1947-48 Palestine, has resulted in the creation of one of the largest and longest standing protracted refugee communities world-wide today. The unresolved question of Palestinian displacement raises important considerations in, what scholars of redress have named, an era of settler colonial reparations. One line of inquiry that remains relevant for thinking about the future of redress to Palestinian displacement is the following: How did an Indigenous Palestinian society with historical ties to land come to be internationally governed as refugees external to the land? Further, how might we think about the history of redress and humanitarianism in the early years of Palestinian displacement as one tied to a broader genealogy of race and settler colonial formations in Palestine?

In the late 1970s, Hasan Khater was the first inhabitant of the Jawlan (Golan Heights), a Syrian land occupied by Israel since 1967, to cross the militarised border and travel to Damascus to study fine arts. Despite his ambition to become a sculptor, Khater was forced to train as a painter, as Israeli security restrictions did not permit him to cross the border with hard materials. Today, despite the ongoing occupation, Khater’s sculptures couch main squares and public spaces in the remaining Syrian villages of the Jawlān, commemorating five decades of relentless political resistance of the native population.

The Jawlan today is home to around 20,000 people, most of them Druze by religion, who live on a land that is dominated by almost equal number of Jewish-Israeli settlers. However, not long ago, this land and its Druze inhabitants were simply Syrian. They were part of a larger Syrian Jawlani community that counted more than 150,000 people of diverse religious and ethnic backgrounds, including Sunnis, Kurds, Armenians and Alawites, among others. Soon after the Israeli occupation, the Jawlan transformed into a borderland; it was cut off from its Syrian continuity, and re-oriented to face Israel. The Jawlani community offers an important perspective on anticolonial world-making, particularly because of its stubborn refusal of colonial integration and its rejection of repeated impositions of Israeli citizenship. However, refusal is not enough to reconstruct a creative sense of liberated being. For this to happen, self-realisation of a capable independent existence is essential to disengagement from colonial mental violence. Many local artists in the Jawlan have been the main social force in creatively imagining new horizons of freedom. This research project began in the summer of 2018, as an attempt to examine not simply how art reflects reality, but how it transforms it. Understanding racial capitalism in Africa: a study of the Nigerian oil-dependent capitalist economy21/10/2020

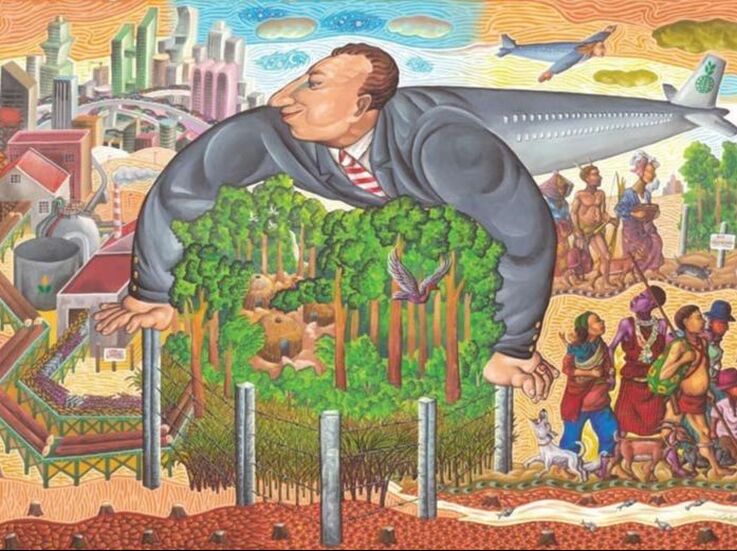

My Identities article, ‘The capital, state and the production of differentiated social value in Nigeria’, problematises the Nigerian oil-dependent capitalist economy through the perspective of the Black radical tradition. Using Cedric Robinson’s concept of race, I analyse the racialism inherent in the Nigerian capitalist economic relations and the accompanying contradictions. Capitalism is a very powerful historical force that has influenced and still influences diverse social, political and economic landscapes. The state is an agency through which the association of individuals are entrusted with the administration of the affairs of a given society. Both the capital and state are essential agencies in the entrepreneurial model of the capitalist mode of production.

Marxist scholars present capitalism as an unfair system that engages in unequal distribution of the social wealth generated by the society. Marx argues that the capitalist society is divided along class line and the economic factor remains the most decisive determining factor in shaping capitalist dynamics and its contradictions, while culture and other human pre-occupations play a role but not the decisive one. The working class, Marx maintains, is the revolutionary class that will eventually transform the capitalist economy.

'Free Kashmir', reads the placard held by a young Indian woman during an anti-Citizenship Amendment Act agitation at the Gateway of India, Mumbai, on 6 January 2020. That India cannot tolerate such 'separtist sentiments' is central to the outrage over the placard. People in her supporting circle defend it on the grounds that it meant freedom from Internet lockdown imposed since 5 August 2019 across Kashmir. The woman comes out with a statement: 'I was voicing my solidarity for the basic constitutional right'.

As Kashmiris, what does it mean to be shown solidarity with terms and conditions, one that disallows a Kashmiri from envisioning their freedom but dictates its meanings and interpretations for them? In our Identities article, 'On Solidarity: Reading Love, Loss, and Longing in Kashmir', we engage with the question of solidarity through a critical reading of Sahba Husain’s book Love, Loss, and Longing in Kashmir. The multiple ways in which claims of solidarity are articulated by Indian ‘progressives’ often result in reflecting dominant narratives that obfuscate the lived realities of the occupied Kashmiri people. This is brought forth in the piece through an analysis of how the concepts of disillusionment, alienation, resilience find expression in these works.

It may be a truth not so universally acknowledged that editing a special issue of a journal can often be a nerve-wracking affair. Guest editing a special issue for Identities titled 'Archives of Coloniality and Solidarity: Kashmir and Palestine, in medias res', goes beyond this experience. The razored concertina wires, the militarised checkpoints, the open brutality, the violence against the living and the dead, and the permanent warfare against entire populations that characterise the experiences of Palestinians and Kashmiris permeate this special issue. These experiences may not be exceptional to those editors and authors working on state violence and occupations. However, the experience itself must be acknowledged.

Author emails in the summer of 2019 demonstrate the porous ways in which the occupations of Palestine and Kashmir have pervaded this guest editing process. |

|

Explore Identities at tandfonline.com/GIDE |

|

The views and opinions expressed on The Identities Blog are solely those of the original blog post authors, and not of the journal, Taylor & Francis Group or the University of Glasgow.