|

|

|

Cross-posted from British Sociological Association

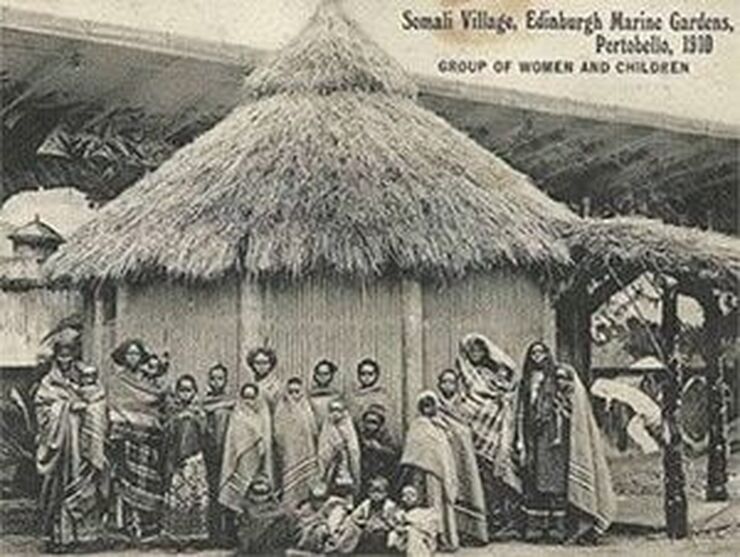

How is history written and by whom? These are questions that have been raised with frequency across the decolonising movement and in particular, by the Cadaan Studies movement, which has focused on knowledge production relating to Somali people. Started in 2015 by Harvard doctoral candidate, Safia Aidid, the movement provides a framework through which to critique the role of whiteness and white privilege in shaping narratives about Somali people. The canonical work of Glaswegian-born I.M. Lewis has come under particular scrutiny not in the least due to his twin roles as anthropologist and administrator for the British colonialists in (then) British Somaliland in the 1950s. Yet whilst the colonialist activities of a Scotsman in Somalia shaped global discourses about Somali people, the narratives of Somali people in contemporary Scotland, many of whom now live in the same area of Glasgow in which Lewis was born, remain absent from local and transnational histories. We unravel and critique this absence. Today in Scotland, there is a Somali population of up to 4000 people. The population has grown in the main since 1999, following the state-enforced dispersal of asylum seekers to sites around the UK. Despite residing in Scotland for nearly two decades, the Somali population continues to be framed in these terms, considered ‘new’, as ‘migrant’; as without history prior to arrival in Scotland and without historical links to Scotland. These narratives obscure a much longer history of Somali people living in Scotland, and of Scotland’s relationship with Somalia.

0 Comments

In January 2019, the news broke that women ‘rescued’ by the British government’s Forced Marriage Unit (a joint Foreign and Commonwealth Office and Home Office initiative) were being made to pay for the costs of their protection. If they were unable to pay outright, they had to agree to sign up to a loan, usually in the region of £700, to cover the costs of food, flights and accommodation. Their passports were confiscated and held until the loan had been repaid in full (Guardian, 2 January 2019). There is much to be said regarding the implications of this policy in relation to the government’s vocal concern about coercive cultural practices, and the matter of the passport seized as collateral for an involuntary debt requires particular attention. In ‘saving’ women from being taken from the UK against their will, the state then ensures that they are unable to leave the UK.

The Forced Marriage Unit thus ‘liberates’ women from situations in which passports are routinely seized as a means of control (such as by family members attempting to prevent women from fleeing a forced marriage) by using precisely the same mechanism of immobilisation. Further, while British state institutions tend to present forced marriage as an adherence to (anachronistic) cultural norms, they also critique its underlying economic or practical motivations, with marriage to a UK national aiding in access to residency and citizenship. As such, forcing women into debt in order to avoid an unwanted marriage appears to collude with, rather than contest, the notion that a woman’s value is primarily financial: whether being forced into marriage or ‘rescued’ by the state, she must earn her keep.

Due to the accessibility of the internet and the ability of online spaces to bring people together, platforms like social media sites and web forums have allowed globally dispersed communities to engage in conversations about identity and belonging. For my Identities article, ‘Connectivity, contestation and cultural production: an analysis of Dominican online identity formation’, I collected and analysed text data from a web forum that I call ‘DRLive’ to show the kinds of identity discourses that happen online. This site caters to all things Dominican Republic, with free and open forum pages where Dominicans and non-Dominicans participate in discussions covering numerous topics. Adding to work on diaspora, migration, and cultural production among Dominicans, I propose forums and other virtual spaces as additional sites where diasporic and non-diasporic Dominicans come together to talk about and challenge evolving interpretations of identity, history and cultural memory.

Cultural memory, which is defined as a collection of commonly shared historical moments and experiences, is passed on and shared over time by members of a nation. In the case of this forum, for example, I find that ‘the contrived historical narratives propagated in the Dominican Republic throughout the 19th and 20th centuries continue to inform how Dominicans in the country and in the diaspora interpret and construct Dominicanidad.’ Work on virtual spaces often seeks to address how migration might affect the maintenance of cultural memory, especially as second- and third-generation immigrant communities emerge far from their homeland.

Since 2015, several European countries have witnessed an unprecedented involvement of citizens in forms of refugee support which have been gradually identified in public discourse as a newly emerging ‘culture of welcome’. While acts of solidarity are not a new phenomenon, these emerging mobilisations, often enacted by people with no activist background, hint at an inherent tension between the official stance on the ‘refugee crisis’ and the grassroots responses to it.

The experiences of ordinary people hosting refugees in their homes, often with the intermediary role either of NGOs or of local authorities, shows that no matter how micro or widespread, these emerging housing arrangements make for a ‘social lab’ in which broader societal issues can be fruitfully revisited. Interestingly, refugee hospitality initiatives relocate forms of pro-refugee support from the public arena into the intimate space of the domestic. In doing so, they shed light on emerging practices of ‘domestic humanitarianism’, understood not just as an impulse to offer care tied to specific notions of ‘responsible citizen’, but as a mode of helping that takes place inside the home. At the same time, they evoke the contentious reconfiguration of the mainstream views and boundaries of home – who is entitled to belong in a place and call it home – at the domestic, community and national levels.

Superdiversity and integration are prominent yet contested terms to capture increasing population heterogeneity due to migration and participation by, and inclusion of, migrants in the arrival context. These terms have been criticised for ignoring the implication of established residents in processes of integration and their contestation of migration-based diversity. Yet, to date, limited research has shown how established residents differ in responding to superdiversity and how they conceive of integration.

My Identities article, ‘Towards a differentiated notion of the mainstream: superdiversity and residents’ conceptions of immigrant integration’, sets out to explore variations in established residents’ responses to diversity and the extent to which they consider themselves as playing a role in integrating newcomers. It draws on fieldwork that captured the reactions to the installation of a large asylum seeker reception centre on the outskirts of a large German city. Interviewing residents of the neighbourhood and participating in meetings of the 'local partnership', the article counters the common assumption in the literature that migration-related diversity is either contested or seen as a banal aspect of everyday urban life.

The recent visit by Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi to Bangladesh to attend celebrations marking 50 years since the birth of the country following the Liberation War in 1971 has drawn attention to the difficult task of building a nation on the back of a brutal and bloody civil war. At least four people were killed by police in the Bangladeshi city of Chittagong during a demonstration against Modi’s visit. Protesters from Hefazat-e-Islam Bangladesh, and counter protestors aligned with Bangladesh’s governing Awami League party, represent the central divide in Bangladeshi politics, between those who tie national identity to Islam and those who tie national identity to ethnicity and the Bengali language. This is a divide sometimes understood as one between those who ‘collaborated’ with the Pakistani military and those who participated in the independence struggle. On the Golden Jubilee of Bangladesh’s birth, this divide continues to shape Bangladesh’s political landscape today.

Using the case of the ‘Urdu-speaking minority’ in Bangladesh, my Identities article, ‘Displacement, integration and identity in the postcolonial world’, considered what the experience of minorities displaced during the Liberation War tells us about the Bangladeshi national imagination today. Their own voices, and the narratives of identity and integration in which they are situated, are revealing of the nature and boundaries of the nation state fifty years on from the country’s birth. Although the country remains divided around the role or significance of religion versus culture, and between those who ‘collaborated’ with the Pakistani military and those who participated in the independence struggle, there are older divides at work here too. Some of those who ended up on the wrong side of the Liberation War are accepted into the nation today. Here colonial narratives of ‘population’ versus ‘people-nation’, ‘community’ versus ‘citizen’ structure exclusion not only through narratives of the country’s foundation myth (as commonly assumed) but also through poverty and social space.

If we look at it sociologically, we see that blood has been associated with a spectrum of positive and negative qualities, from being a symbol of sacred bonds to outright impurity. Blood represents family ties, contains codes and data about our physical health and wellbeing, and is also pervasive in religious symbolism. The blood of a martyr or Messiah represents some truth about salvation, and the relation between humans and the divine.

My Identities article, ‘Could we use blood donation campaigns as social policy tools?: British Shi’i ritual of giving blood’, investigates the socio-cultural settings behind a nationwide blood donation campaign in the United Kingdom, the Imam Hussain Blood Donation Campaign – or in brief, IHBDC. The IHBDC was founded in Manchester by a few young Shia Muslim university students. Almost fourteen years after its foundation, IHBDC is one of the largest cross-ethnic blood donation campaigns collaborating with NHS Blood and Transplant, in England, as well as the Scottish National Blood Transfusion Service (SNBTS). The community activists see this campaign as a way of honouring the sacrifice of their martyr and spiritual leader, Imam Hussain, as well as addressing a health-related social problem. As there is a difference in the frequency of blood types between different ethnic groups, in an increasingly multi-ethnic society, activists are needed to take on the responsibility of assisting with balancing the blood stock level at any given time. The conjunction of religious mythology of blood and donation activism has proved to be effective. Activists are getting more political recognition for their community, while contributing to tackling a social problem. The clearest mark of such recognition is the passing of motions supporting the campaign in both the London and Scottish Parliaments.

The latest evidence of Europe’s anxieties about immigrant (non-) integration comes in the form of a draft declaration released by Germany, France and Austria in November 2020. The declaration pushed for stricter EU integration rules, stating, ‘It needs to be possible to sanction sustained refusal to integrate more strongly than has been the case to date’.[1] Yet, each European country has always had a wide scope for determining how to admit and incorporate new members, and countries have not refrained from introducing strict measures. The latest trend is to start the integration process as early as possible – even before the migrant arrives, when traveling to Europe is just a dream. In recent years, France (2007), Denmark (2010), the UK (2011), the Netherlands (2006) and Germany (2009) have all introduced pre-integration measures for nationals of certain countries.

In my Identities article, ‘Cultivating membership abroad: Analyzing German pre-integration courses for Turkish marriage migrants’, I examine the aims and methods of German pre-integration courses offered to Turkish marriage migrants in Istanbul. Using participant observation and in-depth interviews, I also examine instructor perceptions and student reactions to the curriculum.

Around 9.30am on Thursday 13 May I checked my phone for messages, as I was about to start making preparations for Eid dinner later that evening. One of the No Evictions Network activists had posted a photo of an immigration enforcement van in Kenmure Street in Pollokshields and said that he was going to investigate what was happening, and asked others in the network to come down to support him. As more and more members of the network arrived, it transpired that immigration officers had raided the home of two men, Sumit Sehdev and Lakhvir Singh, and put them in the van. The immigration van couldn’t leave because it was surrounded by activists, and one of them had got under the van (and would stay there for eight hours to ensure it wouldn’t go anywhere). Activists reported that Police Scotland were helping immigration officials by trying to persuade the activists to disperse. In solidarity, thousands of Pollokshields locals as well as people from across the city gathered to prevent this immigration raid. The two men, both migrants from India, were eventually released.

Throughout the day I was reading news reports and comments on social media about how friendly and welcoming the people of Glasgow are to newcomers, as if that was enough explanation for the overwhelming solidarity against this particular immigration raid. Whilst Glasgow has a reputation for being friendly, it also has a history of racism going back to the days of empire and the attacks on black seamen in 1919. I also read reports crediting the release of the two men to the actions of individual activists. This is mistaken.

In 2015, a toddler gained world fame most tragically. Alan Kurdi, a three-year-old boy, drowned alongside his brother Ghalib and their mother Rehanna Kurdi while trying to cross the Aegean Sea from Turkey to Greece. The photographs of his washed-ashore body lying face down on the beach on the Bodrum peninsula in Turkey travelled around the world and caused a global outcry.

These images were widely modified and re-mediated in forms of cartoons, drawings, graffiti, sand sculptures and re-enactments to raise awareness of the EU’s lethal borders. Moreover, they became a token for solidarity with people seeking refuge in Europe. Alan Kurdi represented the death of so many others and thus became a symbol for the protracted disaster in the Mediterranean Sea. The dead child’s images represented more than anything else the fear, anger and hope revolving around the so-called ‘EU refugee crisis’ in 2015. For a brief moment, the global indignation caused by the photographs made many critics of the EU border management believe that EU policies towards migrants and refugees might change. While the outrage about the EU’s role in producing this deadly sea has triggered scattered protests in the past, nothing spurred such a vehement reaction as the images of the dead child. Not only members of civil society but also policy makers expressed sorrow over his tragic death. The cruelty of the border regime became tangible and even contributed to the opening of the Balkan Route.

As socially committed and Spain-based researchers, we have long been amazed by the rhetorical power of the integration discourse (in this case, immigrant integration). This discourse has charmed and brought together people with different political orientations, even seducing numerous activists who usually adopt radically critical stances towards existing social oppressions (for example, capitalism).

However, such criticism does not frequently focus on integration. On the contrary, integration measures are often thought of as useful 'recipes' against racism, or even as its opposite. Hence, the 'benign' concepts associated to integration such as 'diversity', 'participation', 'active citizenship', 'interculturality', etc. have been often uncritically appropriated by non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and leftist movements, with allegedly inclusive or even anti-racist aims. The aim of our Identities article, ‘Elective affinities between racism and immigrant integration policies: a dialogue between two studies carried out across the European Union and Spain’, is to deconstruct such optimistic rhetoric, showing that racism and integration are closely embedded, and thus questioning the transformative potential of integration policies. With this aim, we have put into dialogue our PhD research pieces (one is complete, the other is being finalised), which respectively focus on the 'soft law' European Union framework for the integration of third-country nationals and Spanish/Andalusian immigrant integration policies.

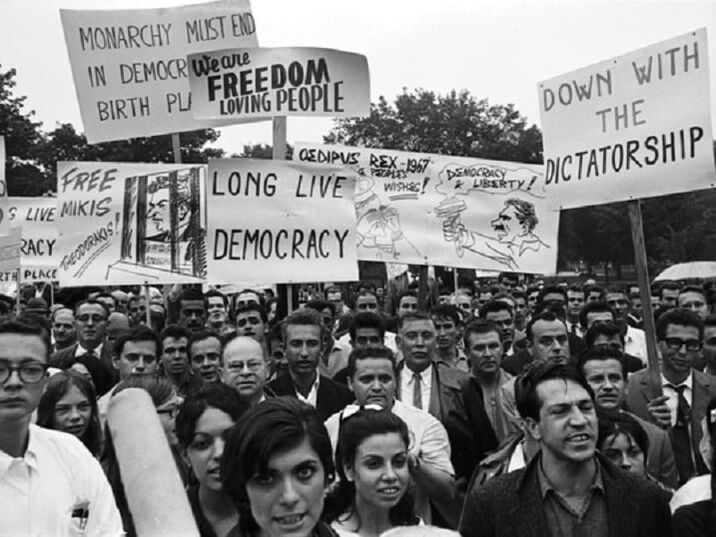

You’ve heard the story: Our protagonist sets off on an adventure, overcomes perilous challenges and returns home a wiser, braver and more principled person. In my Identities article, ‘On the value of failing and keeping a distance: narrating returns to post-dictatorship Greece’, I offer a very different story of antiheroes, ambivalent adventures and fraught returns. Our protagonists were young people fleeing Greece during the dictatorship and returning home a decade later to rebuild their country.

Departures In the early hours of 21 April 1967, Athenians woke to soldiers and tanks in the streets and military music on the radio. The army had taken power overnight. Since the Greek civil war (1946–1949), left-wing Greeks lived under police surveillance, deprived of critical documents necessary for work and studies. With the new regime threatening incarceration of dissidents, our protagonists left for Canada. Some left urgently, others through prepared departures; some left with passports bought on the black market, others through ‘legitimate’ means; some jumped ship as young sailors at North American ports, others were sponsored by family members already living abroad.

Bermo carries my two year old son on one shoulder as we stroll down the main street in Antwerp, the beautiful medieval city in Belgium. My son uses Bermo’s soft turban as a place to rest his head, struggling to keep his eyes open. The photographer that follows the two of them in an attempt to get his best shot is really disturbing in his intensity and he has not even asked if he can take a photo. Bermo, used to being shown such excitement, pretends simply to ignore him. Bermo is not a celebrity as one might expect but a migrant worker from Niger that in his everyday life back home moves between the pastoral area and the city, where he struggles to make a living. Here I suspect that the combination of his clothing and dark skin, as well as the white body of my son, is arousing interest. While this particular event was rather extreme and took place prior to the so-called ‘crisis of migration’ in Europe, I have seen time and again WoDaaBe being perceived as belonging to the slot of the ‘exotic others’.

In my Identities article, ‘Global citizens, exotic others, and unwanted migrants: mobilities in and of Europe’, I focus on those portrayed as exotic to ask larger questions about otherness in Europe in the present. What kinds of bodies are welcomed in Europe that, after all, has for the last few years been characterised by large headlines proclaiming an ‘invasion’ of people from Africa into Europe? These depictions have often intersected with racialised narratives of Muslims and asylum seekers as threats, simultaneously criminalising and reifying these heterogenous categories. My article is based on ethnographic research in Belgium that consisted of brief visits conducted over a long period of time, wherein I participated in the life of WoDaaBe migrant men, as well as in the lives of other migrants from Niger in precarious positions. Some of these individuals I knew going on 20 years, having met them a long time back, while undertaking my two-year long PhD fieldwork in Niger.

As the human misery in Lesbos, Malta and the Mediterranean Ocean hits the world media, a debate has emerged on how to speak about this crisis. Some argue that the public debate and part of the media coverage has become ‘too emotional’. A few voices emphasise the lack of context, including the history of war and oppression in the region from which a majority of the Moira refugees and migrants have travelled in search of safety.

As a media researcher with an international journalist background, having travelled and resided in countries in the Middle East and beyond, it is hard not to agree with those asking for historical context. Far too often, the public debates on asylum seekers and migrants narrow the scope to the nation’s sustainability. Another argument relates to ‘whataboutism’, highlighting the plight of people who are even worse off, such as in Yemen. For academics and other experts alike, it does make sense to approach refugee discourses from a multi-level perspective. It is hard not to see the high number of Afghan refugees in Moria as related to the last two decades of NATO-led intervention, and the hopes that turned to ashes while the Taliban (again) grew stronger.

In the 1930s, the retired British governess Mary O’Neill lived in Florence in the company of her female co-nationals. A close-knit diaspora of English aristocratic intellectuals and bohemians, they sought to spread English cultural traditions to the Italian masses. They tried to help ordinary Italians enjoy Shakespeare and Renaissance art, not only to dream about glamorous cars and other pleasures of the Jazz Age. Mary O’Neill and her friends greatly contributed to the upbringing and the artistic rise of the young Franco Zeffirelli. But did they manage to gain prestige within their Italian community? Known for their poignant wit, those expat women, whom the locals sarcastically called ‘Scorpions’, were, in fact, totally alienated from a wider Florentine community.

Depicted in Zeffirelli’s Tea with Mussolini, this story of cultural resilience finds a lot of resonance with diasporic reality today. In the large volume of studies on diaspora, an issue of concern is that many expats who speak culturally and civically on behalf of their homeland find zero reciprocity within their local community (Nye 2004; Watanabe and McConnell 2008). Why do highly intellectual expats, who seek to morally enrich their host society, often fail to be accepted by their local communities? This question is explored in-depth in our Identities article, ‘Reflections on diaspora and soft power: community building among female US expats in Southern Europe’, which looks at life experiences of highly educated US-national expat women in Italy and Greece from the 1990s to 2015. They all hold degrees from leading US universities. Many of them are married to local men. And all of them seek to spiritually invigorate their local communities by showing them how to take care of the public space, such as to clean streets from litter and set up shelters for stray dogs and cats. They see these as typical ‘North American civic values’ that they are teaching to their ‘unenlightened’ neighbours.

Undocumented youth, or those young people living in the United States without legal immigration status, encounter significant challenges at important moments in their life, such as looking for their first part-time job or securing a driver’s licence. When they apply for college, they find they are ineligible for many scholarships and all forms of federal financial aid. For many scholars, these significant challenges mean that being undocumented functions as a ‘master status’ – a key aspect of their identity that has a marked influence on their life experiences. Scholars such as Roberto Gonzales argue that for some undocumented youth, ‘learning to be illegal’ is synonymous with experiences of exclusion during the transition to adulthood.

Although legal status certainly shapes undocumented youths’ experiences in applying to and attending college, Laura Enriquez reminds us that other aspects of undocumented students’ identity, such as race or class, also play a significant role in persistent inequalities that shape undocumented college students’ experiences – particularly those feelings of not belonging on a college campus. Enriquez shows that being poor and a first-generation college student influences undocumented students’ likelihood of stopping out of school both earlier in the life course and to greater effect than legal status does. Consequently, she concludes that undocumented status does not function as a master status, but rather, serves as a ‘final straw’ that imparts feelings of not belonging rooted in exclusionary experiences, which tip the scale in the direction of withdrawing or dropping out of college. Her research questions whether undocumented status acts as a master status at all, choosing instead to underscore its affective and relational influence when combined with other master status identities such as race or class.

The fact that some second-generation immigrants were involved in the brutal terror attacks in major European cities such as in Paris in 2015 and Brussels and Munich in 2016 exacerbated xenophobia among politicians and the broad public. These terrible incidents increased scholarly interest in the integration of second-generation immigrants further, and heightened anti-immigrant and anti-Islamic sentiments across Europe and far-right.

In addition to the terror attacks, economic restructuring and growing poverty amongst the working-class have also resulted in the rise of far-right in Germany. This has become visible with the Patriotic Europeans against the Islamisation of the West (PEGIDA) movement and strengthening of the Alternative For Germany (AFD). In this regard, the host society often tends to relate the Turkish second generation's social and economic disintegration to marginalisation and ‘Islamisation’. In such a context, studying the stigmatisation of ethnic minorities and immigrant groups reveals discrimination, stratification and ethnic boundaries. Along similar lines, the destigmatisation strategies of minorities, how they respond to the majority to maintain their dignity, achieve recognition and invest in their integration, are equally revealing. My Identities article, 'Disadvantaged, but morally superior: ethnic boundary making strategies of second-generation Turkish immigrant youth in Germany', examines how social, political and structural changes in Germany increase anti-Muslim, anti-immigrant and anti-refugee sentiments. By drawing on in-depth interviews and ethnographic data with twenty second-generation Turkish immigrant youth, the article reveals the kind of stigmatisations Turkish immigrants (the largest Muslim group) face, and, more importantly, how they deal with these stigmatisations in their daily lives.

In my 20 years of doing research that is framed either directly or indirectly by Norwegian authorities, I have come to the conclusion that even, or maybe especially, in Norway where there are close links and allegiances between research and government and where the shared assumption often is that ‘we all want what’s best for people’, there are considerable risks when scholars aim to produce research that is intended to be relevant to stakeholders and society.

In order to get funding and recognition, researchers are subjected to demands to do research in a way that is explicitly relevant to society in the short run. Such short-term relevance is also valued within research institutions and among researchers, and the evaluation of research often uses ‘impact’ as a marker for quality. The value of being relevant is heralded in many contexts, but the drive to be relevant may be problematic as this creates a situation where it may be difficult to steer free of becoming embedded in administrative or political agendas. I have experienced politicians and bureaucrats staying at an arm’s length distance to ensure the independence of my research, but I also have experience with meddling, threats and disappointment. In my Identities article, ‘Taking on the categories, terms and worldviews of the powerful: the pitfalls of trying to be relevant’, I describe some such experiences. Much of my experience as a researcher is as a migration scholar; migration is a field that rapidly moved from the margins to the centre of both society and social science scholarship in the last ten years. This mandates that we have to think about what that entails for the framing and need for our research, but also for our practices and ability to take a critical position in our own work.

Transnationalism is a fundamentally agentic concept. Emerging as a critique to methodological nationalism, it emphasises processes that occur between, beyond – and often in defiance of – the boundaries of the ‘nation state’. Applied to international migration, it stands as a dominant paradigm for framing sustained economic, social and cultural ties maintained by migrants across international borders, and enduringly celebrates the agency of transmigrant actors with fluid connections to countries of origin and destination.

Our Identities article, 'Forced transnationalism and temporary labour migration: implications for understanding migrant rights', takes a very different view of transnationalism. We suggest that, while the tone-setting ‘first wave’ of the transnationalism literature offered an important critique of assimilationist immigration regimes in the global north, its agentic emphasis had little resonance with highly-restrictive guest-worker migration prevalent across the global south – particularly the major migration corridors of Asia. In these settings, state power was then, and still is now, pivotal in circumscribing the transnational existences of millions of migrant workers who emigrate out of economic necessity but are trapped between multiple political and economic interests that ensure their migration is strictly temporary. Though scholarship on transnationalism has typically shied away from defining these temporary labour migrants as transmigrants on account of the narrow scope of activities presumed to be carried out by the remitting labourer, this seems disingenuous.

Migration, like all social issues, is an ever-evolving phenomenon. Recently, the COVID-19 pandemic, the rise of extreme right-wing politics worldwide and the economic and ecological crises, among others, further add to those identified in our Identities article, 'Interwoven migration narratives: identity and social representations in the Lusophone world', published a few years ago.

Surely, the field of Migration Studies demands a constant examination of social changes and, among other things, how they intersect with and influence migration flows and migrants’ life experiences. However, it is important to stress that, alongside new representations of the world and its power dynamics, there are long-standing ones. From the perspective of the Humanities and Social Sciences, it is crucial to understand the ruptures, continuities and accommodations of social representations and the effects these have in shifting or maintaining the status quo. To this end, the argument of our article provides a useful framework to situate the analysis of migration narratives. Specifically, we present three elements of enduring discursive constructions and social representations of commonality among the Portuguese-speaking countries: the ideas of a shared past; a common language; and a sense of community, marked by hybridity and deep cultural ties. Aiming to contribute to the understanding of how deep-seated these ideas are, we explored the intersections, reverberations and clashes of these dominant ideas of Lusophony in migrants’ life narratives, understood as tools to explain, organise and frame the world as well as to make sense of one's self-identity.

Have you ever thought about the way that language is used to frame our understanding of ourselves and other people? It wasn’t many years ago that public transport systems moved from calling people ‘passengers’ to ‘customers’ – a transition that reflects the privatisation of these services, and the now primarily economic nature of the relationship between the service user and provider.

On a global scale, we principally use the language of nation-states to frame self and other. These are not empty frames, but full of meaning, rights and responsibilities. Nation-states ascribe citizenship, enact power, arrange economies, provide healthcare and education (to varying degrees), determine freedom and influence (consider the power of a British passport over, say, an Iranian one), and control the movement of goods and people. But what happens when people challenge this nation-focused way of divvying up the world? How do we see the nationally non-compliant, and how does that influence how we ourselves are then framed?

In our Identities article, 'Private empowerment and public isolation: power in the stories of migrant ‘Mother-Poles’, we seek to understand what kinds of empowerment and disempowerment narratives can be linked to migrant motherhood and mothering in the case of Polish women raising their children abroad.

By linking two perspectives of migrant mothers themselves, as well as at looking at stories of adult children brought up by Polish mothers outside of their country of origin, we investigate maternal power which may, on the one hand, ground women as managers of their households but, on the other hand, does not seem to alleviate the general isolation they face in regards to the broader society. To gain a better understanding of the specific type of Polish migrant mothers we call ‘Mother-Poles’, it is vital to clarify that the particular Mother-Pole construct is a significant yet somewhat blurry notion of Polish motherhood. Moulded from both a religious inspiration of the Virgin Mary’s cult in Catholicism, and an experience of managerial matriarchy which described women’s resourcefulness during the time of State Socialism in the Central and Easter European block, the Mother-Pole figure is omnipresent in religious, social and political discourses, imbuing a reference point for the everyday life of many Polish women over 40.

Difference is something that exists in the bodies and culture of ‘others’

Sara Ahmed, 2007 In the wake of the recent intensification of activism and debate on why and how Black Lives Matter it is important to keep interrogating the multifaceted ways in which racism is pervasive within institutional practices – often in not immediately visible ways. In the UK, the current hostile environment (Grierson 2018) is designed to create forms of social disadvantage for migrants, especially those in situations of vulnerability, feeding into an ever expanding and invisibly coercive system of oppression. Our London-based research explored the kind of support that asylum seeking and migrant women receive by charities, especially around mental health. Compared to statutory services, charities are able to better understand and address the complex intersection of social, political, economic and emotional factors at stake in mental health, as opposed to psychiatric diagnoses which often tend to decontextualise people’s experiences of distress. Third Sector Organisations (TSOs) are well suited to respond to complex needs of asylum seeking and refugee women because the support they provide relies on empathetic understanding for different aspects of these women’s lives – ranging from acknowledging culturally embedded notions and experiences of mental health to being responsive to the structural position they are placed in by the state and society. Both material and emotional support are particularly important for newly arrived migrants, who have weaker social ties in the host country, are often less able to navigate support systems due to language barriers and because they are unfamiliar with or denied access to statutory services.

As the COVID-19 pandemic rendered people around the world homebound, home for some US citizens turned out to be the colonial town of Granada, along the shores of Central America’s largest lake, Lake Nicaragua, in a country many of these settlers had known only as the bloody battleground of the revolutionary Sandinistas and the counter-revolutionary (US-Backed) Contras.

These ‘expats’ began migrating to Nicaragua, in earnest, in the early 2000s (though an American presence in the country extends much further back in history). They are drawn by a quest for adventure, but also by affordable, spacious Colonial-era homes, maids and gardeners, and upscale restaurants in a country ranked second poorest in Latin America. In stark contrast to the attention focused on ‘caravans’ of migrants fleeing Central America en route to the US, these US citizens and other north-south migrants go generally unnoticed in the public discourse on global migration. My Identities article, ‘Rooted in relative privilege: US ‘expats’ in Granada, Nicaragua’, examines this group of international migrants, incorporating some of the same concepts used to study their counterparts moving from the Global South to the Global North. Based on fieldwork in Granada, Nicaragua and in-depth interviews with 30 US citizens who have made their homes there, I focus on how these individuals negotiate a sense of identity and belonging as US citizens residing full-time in Nicaragua.

Korea has been said to be one of the most racially and culturally homogenous countries in the world. Although many critics claim that this is a 'myth', it is true that the country has not suffered from the racial and religious conflicts that have troubled so many countries. This alleged racial homogeneity may make a different race the primary indicator of 'the stranger' in Korea.

Thus, I was somewhat surprised by the descriptive statistics from a nationally representative survey of the permanent and naturalised immigrants in Korea conducted in 2013. According to the survey, the majority of immigrants who experienced perceived discrimination believed that they were discriminated against because of their national backgrounds, and not race, religion or economic status. From the respondents’ perspective, Koreans seem to be very proud of their nationality. If, as the immigrants claim, Koreans are so proud of being Korean, what is the source of that national pride? Further, could it be the way they justify discrimination against immigrants? My Identities article, 'Constructing Chineseness as other in the evolution of national identity in South Korea', addresses these questions. Drawing on scholarly publications, newspapers, policy reports, surveys and films, I compared two different Chinese immigrant groups who came to Korea in different eras. I traced the narratives of Chineseness used to construct Chinese immigrants as strangers and examined how these narratives are related to Koreans’ evolving self-perceptions. The country’s national goals and sources of pride – in particular, historical eras – constitute the national subjectivity. As the most immediate strangers, Chinese immigrants have been easy targets for Koreans to demonstrate and confirm the new national identities they desire. |

|

Explore Identities at tandfonline.com/GIDE |

|

The views and opinions expressed on The Identities Blog are solely those of the original blog post authors, and not of the journal, Taylor & Francis Group or the University of Glasgow.